With the increasingly severe energy crisis and environmental pollution, biodiesel has attracted widespread attention as a renewable and clean alternative fuel. This paper investigates the effects of B40 biodiesel on diesel engine performance and emissions. By analyzing the physicochemical properties of biodiesel, referencing existing research data and literature, and combining these with experimental results, the study details the impact of biodiesel on engine power output, fuel economy, combustion characteristics, and pollutant emissions. The results show that biodiesel affects engine power and fuel economy to some extent, increases nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions from the engine, and changes the proportion of NO2 in combustion products, resulting in a slight increase in NOx levels in SCR-treated exhaust.

- Open Access

- Article

An Experimental Study on the Performance and Emissions of Diesel Engines Using Biodiesel

- Qiyin Chai *,

- Tan Feng,

- Liangpu Zhou,

- Shaorong Zhang,

- Lihong Dai,

- Zhen Chen

Author Information

Received: 17 Aug 2025 | Revised: 23 Sep 2025 | Accepted: 14 Oct 2025 | Published: 23 Oct 2025

Abstract

Keywords

1.Introduction

With the rapid advancement of the global economy, the energy demand continues to increase, while traditional fossil fuel reserves are steadily depleting. The considerable pollutants produced from their combustion have resulted in significant environmental harm. As a result, the development and adoption of renewable and clean alternative energy sources have become a worldwide imperative. Among renewable fuels, ammonia has emerged as a promising carbon-free energy carrier with mature infrastructure for production, storage, and transportation. Despite its poor combustion properties, Zhu and Shu [1] demonstrated that blending ammonia with combustion promoters enables its practical application in internal combustion engines while significantly reducing CO2 emissions. Zhang et al. [2] developed an online big-data monitoring and assessment framework for evaluating IC engine performance with various biofuels, demonstrating that lamb fat biofuel (LFB) outperformed both waste cooking oil biofuel (WCOB) and conventional diesel across multiple performance indicators, including vibration characteristics, brake thermal efficiency, and friction power. As a renewable fuel, biodiesel is widely recognized as an effective solution to energy and environmental issues, owing to its superior combustion characteristics and lower emissions from incomplete combustion. Nonetheless, the differences in physicochemical properties between biodiesel and Traditional diesel can influence diesel engine performance and emissions. Consequently, thorough research into the effects of biodiesel on diesel engine performance and emissions is of considerable theoretical and practical significance.

2.Physicochemical Properties of Biodiesel

Biodiesel is a long-chain fatty acid monoalkyl ester [3] derived from the esterification of vegetable oils, animal fats, or waste oils. Its molecular structure is rich in oxygen atoms, which facilitates more effective oxygen uptake during combustion. This characteristic not only improves combustion efficiency but also reduces the formation of byproducts from incomplete combustion.

The importance of understanding fuel physicochemical properties extends beyond traditional biodiesel applications. Recent studies on alternative fuels have highlighted how fundamental properties such as density and viscosity critically influence spray formation and combustion characteristics. For instance, research on synthetic fuels has demonstrated that fuel density directly correlates with injection parameters, affecting the discharge coefficient and spray penetration patterns under various temperature conditions [4]. These findings underscore the universal significance of physicochemical properties across different fuel types.

Additionally, biodiesel differs from Traditional diesel fuel in terms of density, viscosity, and flash point, all of which have a significant influence on the injection systems and combustion processes of diesel engines. The physicochemical properties of B40 biodiesel are summarized in Table 1. Compared to standard diesel, B40 biodiesel maintains a normal cetane number, displays a slightly higher density, possesses lower kinematic viscosity, and achieves sulfur content levels well below those required by the National IV standard. Notably, its flash point remains within the standard range.

Physicochemical properties of B40 biodiesel.

| Project | Detection Result |

|---|---|

| Cetane ratio | 53.6 |

| Density (15 ℃) | 869.7 (kg/m3) |

| (40 ℃) | 3.99 |

| Sulfur content | 1195 (mg/kg) |

| Flash point (closed mouth) | 78 (℃) |

3.Influence of Biodiesel on Diesel Engine Performance

3.1.Power Performance

Power performance is a crucial indicator for assessing diesel engines. Studies have shown that biodiesel displays unique characteristics in terms of power output compared to Traditional diesel. Although the higher oxygen content of biodiesel can promote more complete combustion and enhance engine power under certain conditions, its comparatively lower calorific value [5] continues to be a limiting factor. The challenge of maintaining engine power with alternative fuels is not unique to biodiesel. Lai et al. [6] found that gasoline/hydrogenated catalytic biodiesel blends exhibited varying ignition boundaries and combustion characteristics, with G50H50 blends showing potential as diesel substitutes despite modified combustion behavior. This aligns with our findings of a slight power reduction when using B40 biodiesel. Although B40 biodiesel has a higher density, this advantage does not fully offset its lower calorific value, resulting in an overall lower energy density compared to traditional diesel. As a result, when used in equal volumes, biodiesel provides less energy than diesel fuel, leading to a slight reduction in engine power [7].

3.2.Fuel Economy

Fuel economy is primarily reflected in the fuel consumption rate. Experimental data indicate that the fuel consumption rate for biodiesel is higher than that of traditional diesel. As reported in [3], biodiesel’s fuel consumption is approximately 10% higher than that of traditional diesel. In this study, fuel economy was also evaluated under conditions ensuring equivalent power output.

3.3.Combustion Characteristics

Biodiesel exhibits unique combustion characteristics compared to traditional diesel. Its higher oxygen content leads to a shorter ignition delay, promoting faster and more complete combustion. In addition, the higher cetane number of biodiesels improves auto-ignition efficiency and further reduces the combustion delay. However, its relatively high combustion temperature enhances combustion efficiency but also contributes to increased nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions.

4.Influence of Biodiesel on Diesel Engine Emissions

4.1.Particulate Matter (PM) Emissions

Particulate matter is one of the major pollutants emitted by diesel engines. Studies have demonstrated that the use of biodiesel can significantly reduce particulate emissions. This is attributed to the more complete combustion of biodiesel, which minimizes the production of incomplete combustion byproducts. Furthermore, the high oxygen content in the molecular structure of biodiesel helps suppress particulate formation. The extent of particulate reduction with biodiesel varies under different operating conditions; for example, during heavy-duty operation, biodiesel can reduce soot emissions by more than 30% [7]. Zhang further emphasized the importance of proper after-treatment system design, particularly for diesel particulate filter (DPF) reliability when using biofuels [8] .

4.2.Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) Emissions

Nitrogen oxides (NOx) remain a major pollutant in diesel engine emissions. Studies have shown that the use of biodiesel may result in a slight increase in NOx emissions. This is primarily because biodiesel combustion typically occurs at higher temperatures and with greater oxygen availability than Traditional diesel fuel. Specifically, biodiesel leads to higher in-cylinder combustion temperatures and provides additional oxygen, both of which facilitate NOx formation. Modern post-treatment systems employing Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) technology are capable of meeting emission standards for Traditional diesel engines by appropriately adjusting urea injection control parameters. The increase in NOx emissions observed with biodiesel combustion is consistent with broader alternative fuel challenges. Bao et al. [9] reviewed exhaust gas after-treatment systems, noting that selective catalytic reduction (SCR) technology is essential for NOx control in diesel engines using alternative fuels.

4.3.Emissions of Other Pollutants

The high oxygen content in biodiesel promotes more complete combustion within the cylinder, thereby reducing the formation of incomplete combustion products. As a result, biodiesel use can significantly decrease the emissions of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbons (HC) during the combustion process.

Our finding of reduced particulate emissions with B40 biodiesel aligns with the broader benefits of oxygenated fuels. Zhang [8] extensively analyzed DPF failure mechanisms, noting that fuel oxygen content significantly influences soot formation and oxidation rates, which is particularly relevant for biodiesel applications with their inherently higher oxygen content.

5.Experimental Research

To further investigate biodiesel’s impact on diesel engine performance and emissions, this study conducted a series of experiments. The tests utilized a four-stroke direct-injection diesel engine. Following the methodology trends in alternative fuel research, our experimental approach incorporated comprehensive monitoring similar to Zhang, M.’s [2] big-data framework for biofuel assessment. This ensures reliable data collection for performance evaluation under various operating conditions. When comparing Traditional diesel with B40 (a 40% biodiesel-60% diesel blend), it is important to note that B40’s high sulfur content could lead to sulfur poisoning in copper-based SCR catalysts commonly used in National VI standards [10]. To avoid any adverse effects on SCR efficiency or exhaust emission analysis, the experiment utilized a National V vanadium-based SCR catalyst.

5.1.Test Equipment and Methods

The test was conducted on a six-cylinder diesel engine compliant with National V emission standards, featuring a specific displacement, a rated power of 340 kW, and a rated speed of 1800 rpm. The testing equipment included a dynamometer, an AVL i60 gas analyzer (AVL, Graz, Austria), and an AVL particulate sampling system (AVL, Graz, Austria). During the experiment, the engine`s power performance, fuel efficiency, and compliance with National V emission standards were systematically evaluated through cyclic testing.

5.2.Experimental Results and Analysis

5.2.1.Power Output

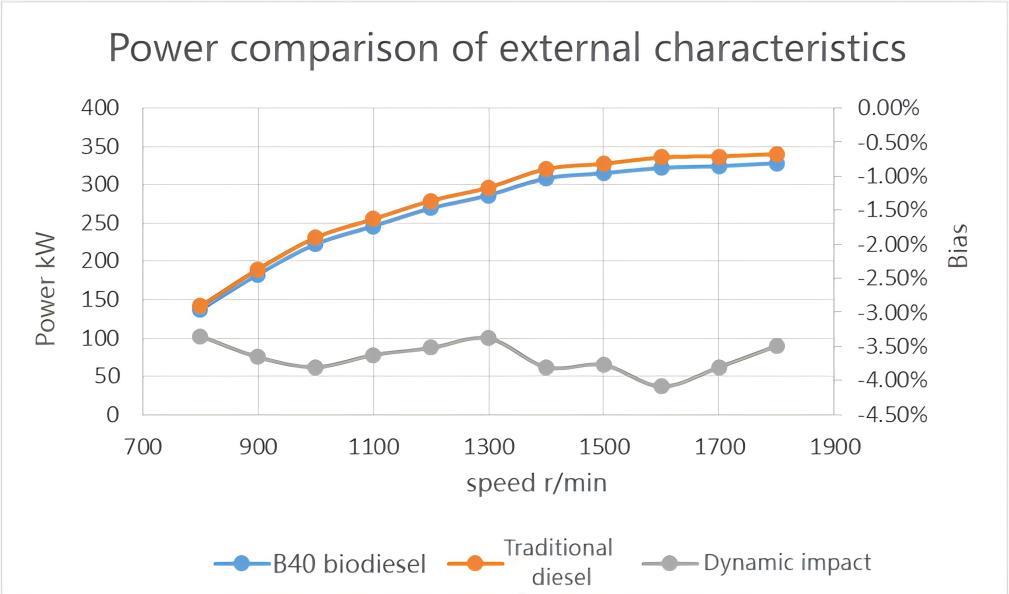

Experimental results indicate that, when maintaining the original diesel engine combustion parameters and controlling key bench conditions (such as intake water temperature, fuel injection temperature, intercooler performance, and exhaust backpressure), the external characteristic power of the engine running on B40 biodiesel decreased by an average of 3.35% compared to Traditional diesel, as shown in Figure 1. This demonstrates that the use of biodiesel can reduce the power output of diesel engines to a certain extent.

5.2.2.Economy

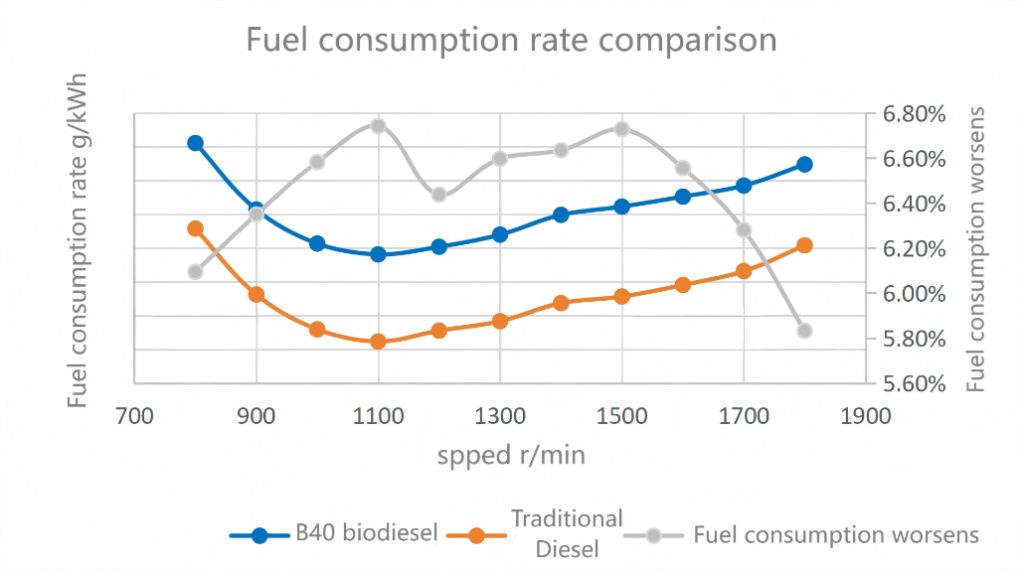

Fuel consumption rate: Due to the slight decrease in power performance, we adjusted the engine combustion parameters to bring the power performance of diesel engines burning biodiesel back to traditional diesel levels. In the external characteristic test, a significant difference in fuel consumption was found. As shown in Figure 2, the fuel consumption rate deteriorated by 5.83% to 6.74%, with an average deterioration of 6.44%.

We also found a significant difference in fuel consumption between the European Steady-state Cycle (abbreviated as ESC in the following text) and the European Transient Cycle (abbreviated as ETC in the following text) according to the National V standard emission cycle. See Table 2 for relevant statistics of the National V standard cycle. In ESC and ETC cycles, B40 biodiesel consumes 0.947 kg and 0.625 kg more than traditional diesel, respectively, accounting for about 6.4% and 5.3%

Statistics of pollutant emission and fuel consumption of cycle engines according to the National V standard.

| Recurrence | Diesel |

NO x g/kWh |

CO g/kWh |

THC g/kWh |

PM g/kWh |

Recirculation Fuel Consumption kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC | B40 biodiesel | 9.552 | 0.062 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 15.705 |

| Traditional diesel | 9.232 | 0.077 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 14.758 | |

| ETC | B40 biodiesel | 9.086 | 0.314 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 12.448 |

| Traditional diesel | 8.923 | 0.513 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 11.823 |

5.2.3.Engine Emission Characteristics

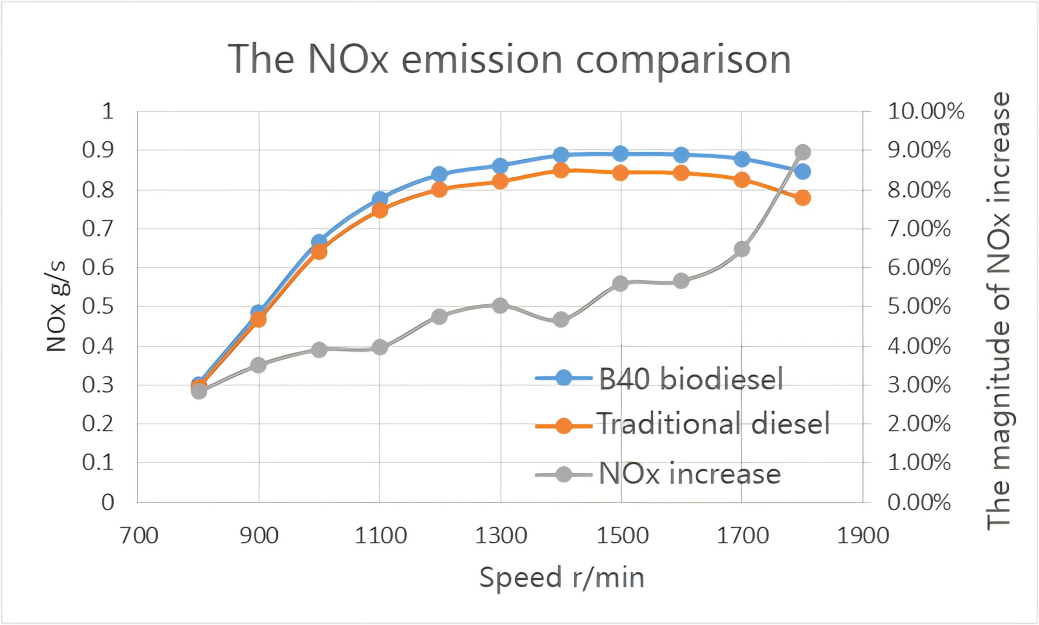

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) emission: When using biodiesel blended fuel, the NOx emission of diesel engines increases slightly. In the external characteristic test, it can be seen that the NOx increases more with higher speed, as shown in Figure 3, with an average increase of about 5%.

We also found significant NOx emission differences in the ESC and ETC cycles according to the National V standard emissions, as shown in Table 2. In the ESC cycle, B40 biodiesel has a NOx ratio of 0.32 g/kWh larger than that of traditional diesel, accounting for about 3.5%; in the ETC cycle, B40 biodiesel has a NOx ratio of 0.163 g/kWh larger than that of traditional diesel, accounting for about 1.8%.

Particulate matter (PM) emission: Through the National V standard emission cycle ESC and ETC, it can be found that B40 biodiesel can reduce certain particulate emissions, as shown in Table 2.

CO and THC emissions: Through the National V standard emission cycle ESC and ETC, it can be found that B40 biodiesel can reduce a certain amount of CO and THC emissions.

5.2.4.SCR Emission Characteristics

By comparing the SCR hardware and calibration with Traditional diesel, we analyzed the NOx emission performance of B40 biodiesel under SCR treatment. As shown in Table 3, when combined with the original engine emission levels from Table 2, the NOx emissions of B40 biodiesel showed a slight improvement compared to Traditional diesel. Specifically, the NOx emission per kWh increased by 0.458 g/kWh during the ESC cycle and by 0.345 g/kWh during the ETC cycle.

NOx data of cycle exhaust according to National V Standard.

| Recurrence | Diesel Oil | NOx (g/kWh) | Exhaust Uniform Temperature (℃) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESC | B40 biodiesel | 1.581 | 376 |

| Traditional diesel | 1.123 | 379 | |

| ETC | B40 biodiesel | 1.280 | 326 |

| Traditional diesel | 0.935 | 330 |

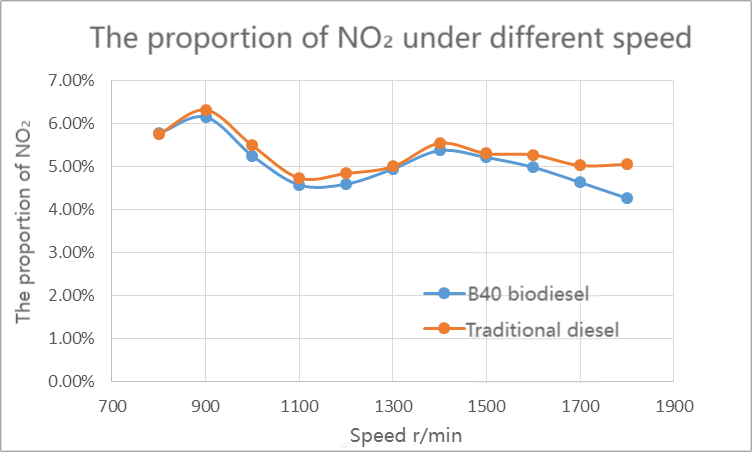

In addition to temperature, the main factors affecting the efficiency of National V SCR are NO2 ratio. As shown in Figure 4, we found in the external characteristic test that the NO2 ratio of B40 biodiesel is lower than that of traditional diesel oil by 1.04% on average and 19.6% relatively. The lower NO2 ratio is the main reason why the NOx discharged from SCR is slightly more than the original NOx.

6.Conclusions

The challenges identified in our B40 biodiesel study reflect broader trends in alternative fuel adoption. As Liu [11] noted in his editorial on alternative fuels in automotive vehicles, the development of cleaner energy sources requires balancing environmental benefits with practical performance considerations. The continued evolution of automotive manufacturing, as discussed by Zhang et al. [12] regarding lignocellulosic biomass applications, suggests that bio-based materials and fuels will play an increasingly important role in achieving carbon neutrality goals.

This study investigated the influence of biodiesel on diesel engine performance and emissions through both theoretical analysis and experimental evaluation. The key findings are as follows:

- Power output: B40 biodiesel reduces diesel engine power by approximately 3.35%.

- Fuel economy: Fuel consumption deteriorates by about 5% when using B40, indicating reduced fuel economy.

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx): NOx emissions increase with B40 biodiesel. Additionally, since National V SCR systems primarily use open-loop control, if the original diesel configuration has a minimal compliance margin, switching to B40 presents a risk of exceeding emission limits.

- Other pollutants: B40 biodiesel significantly reduces emissions of particulate matter (PM), hydrocarbons (HC), and carbon monoxide (CO).

- Sulfur content: The sulfur content in B40 biodiesel is excessively high and must be reduced before it is suitable for use with copper-based molecular sieve SCR systems.

- Given the observed decreases in power output, worsened fuel economy, and increased NOx emissions, it is necessary to calibrate both the combustion parameters and the SCR system specifically for B40 biodiesel. While the reduction in PM, CO, and HC emissions offers notable environmental benefits, these advantages are more relevant for environmental protection than for meeting regulatory emission standards.

Author Contributions: Q.C.: Experimental testing, data organization, writing, verify. T.F.: Review. L.Z.: Edit, verify. S.Z.: Experimental testing. L.D.: Experimental testing. Z.C.: Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFC3707204).

Institutional Review Board Statement: Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its non-invasive computational nature.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Jinhua Wang for his support of experimental resources.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies: No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Zhu, D; Shu, B; Recent Progress on Combustion Characteristics of Ammonia-Based Fuel Blends and Their Potential in Internal Combustion Engines . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm0201001.

- 2.

Zhang, M; Sharma, V; Wang, Z; Jia, Y; Hossain, A.K; Xu, Y; Online Big-Data Monitoring and Assessment Framework for Internal Combustion Engine with Various Biofuels . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2023.100001.

- 3.

Lu, Q. Combustion and Emission Study of Biodiesel Fuel in Direct-Injection Diesel Engines, Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China , 2005.

- 4.

Huang, W; Oguma, M; Kinoshita, K; Abe, Y; Tanaka, K; Investigating Spray Characteristics of Synthetic Fuels: Comparative Analysis with Gasoline . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2024, 3, 2. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2024.100008.

- 5.

Chen, Z; Wang, X; Pei, Y; Zhang, C; Xiao, M; He, J; . Experimental Investigation of the Performance and Emissions of Diesel Engines by a Novel Emulsified Diesel Fuel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 95, 334– 341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2015.02.016.

- 6.

Lai, S; Zhong, W; Pachiannan, T; He, Z; Wang, Q; Experimental Study on Low-Temperature Oxidation Characteristics and Ignition Boundary Conditions of Gasoline/Hydrogenated Catalytic Biodiesel . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 5. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2023.100017.

- 7.

Wang, X.G; Zheng, B; Huang, Z.H; Zhang, N; Zhang, Y.J; Hu, E.J; Performance and Emissions of a Turbocharged, High-Pressure Common Rail Diesel Engine Operating on Biodiesel/Diesel Blends. J. Autom. Eng. 2011, 225, 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1243/09544070JAUTO1581.

- 8.

Zhang, D; Li, M; Li, L; Deng, J; Li, Y; Zhou, R; Ma, L; Failure Analysis and Reliability Optimization Approaches for Particulate Filter of Diesel Engine after-Treatment System . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2025, 4, 2. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2025.100002.

- 9.

Bao, L; Wang, J; Shi, L; Chen, H; Exhaust Gas After-Treatment Systems for Gasoline and Diesel Vehicles . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2022, 1, 9. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm0101009.

- 10.

Yao, D.W; Hu, J.D; Hu, X.H; Li, Y.X; Jin, W.Y; Wu, F; Experimental Investigation on the Coupling Mechanism between Sulfur Poisoning and Hydrothermal Aging of the Cu-SSZ-13 SCR Catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5CY00758E.

- 11.

Liu, Z. Alternative Fuels in Automotive Vehicles . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 7. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm0201007.

- 12.

Zhang, Z; Jiao, Y; Li, Y; Zhang, H; Zhang, Q; Hu, , B; Lignocellulosic Biomass to Automotive Manufacturing: The Adoption of Bio-Based Materials and Bio-Fuels . Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2023, 2, 6. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2023.100012.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.