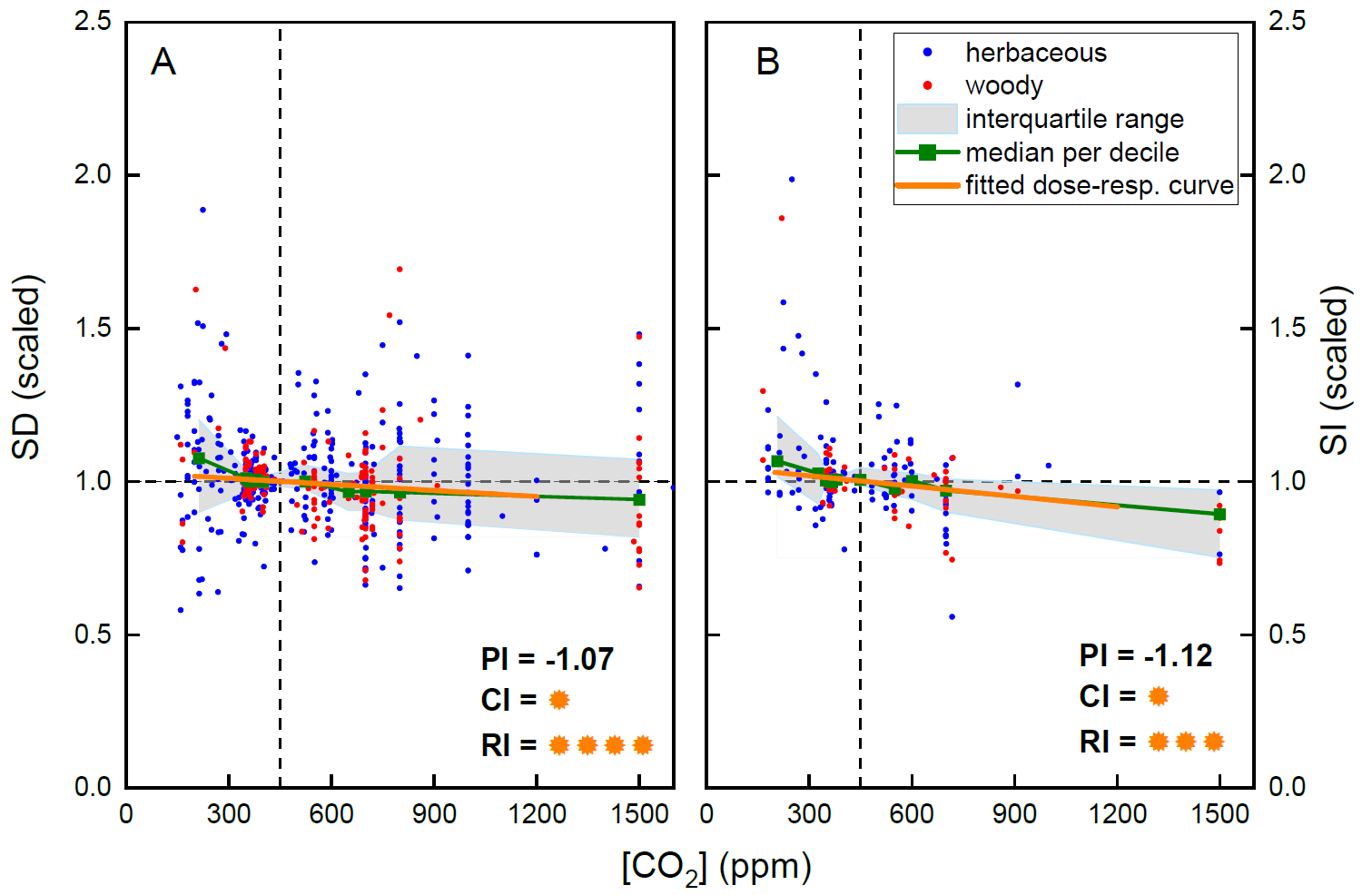

Stomatal density is one of the plant traits influencing leaf gas exchange and is known to be affected by the plant’s environment. Understanding its degree of plasticity to various abiotic factors is therefore important. We conducted a meta-analysis of a wide range of experiments in which plants were grown under different levels of CO2, light, temperature, and water availability, and derived generalized dose-response curves. Although both stomatal density and stomatal index showed a significant negative correlation with CO2 levels, these relationships were weak and only marginally consistent across the analyzed experiments. In contrast, the effect of growth light intensity was positive, highly consistent, and substantially stronger than the impact of atmospheric CO2. Temperature also positively influenced stomatal density, while water availability showed no consistent effects. Based on these dose-response curves, we highlight several caveats when using stomatal density or stomatal index for paleo-CO2 reconstruction. The weak CO2 response, coupled with the strong confounding impact of light intensity, poses significant limitations to the accuracy of such estimates.

- Open Access

- Review

Author Information

Received: 21 Sep 2024 | Revised: 30 Nov 2024 | Accepted: 04 Dec 2024 | Published: 13 Jan 2025

Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

CO2 | daily light integral | light intensity | meta-analysis | paleoclimatology | stomatal density | stomatal index

References

- 1.*Aasamaa K, & Aphalo PJ. (2016). The acclimation of Tilia cordata stomatal opening in response to light, and stomatal anatomy to vegetational shade and its components. Tree Physiology, 37, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpw091

- 2.*Abrams MD, Kloeppel BD, & Kubiske ME. (1992). Ecophysiological and morphological responses to shade and drought in two contrasting ecotypes of Prunus serotina. Tree Physiology, 10, 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/10.4.343

- 3.*Allard G, Nelson CJ, & Pallardy SG. (1991). Shade effects on growth of tall fescue: I. Leaf anatomy and dry matter partitioning. Crop Science, 31, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100010037x

- 4.*Amano S, Hino A,Daito H, & Kuraoka T. (1972). Studies on the photosynthetic activity in several kinds of fruit trees. I. Effect of some environmental factors on the rate of photosynthesis Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 41, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs.41.144

- 5.

Apel P. (1989). Influence of CO2 on stomatal numbers. Biologia Plantarum, 31, 72–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02890681

- 6.

*Apple ME, Olszyk DM, Ormrod DP, Lewis J, Southworth D, & Tingey DT. (2000). Morphology and stomatal function of Douglas fir needles exposed to climate change: Elevated CO2 and temperature. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 161, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1086/314237

- 7.*Asayesh ZM, Arzani K, Mokhtassi-Bidgoli A, & Abdollahi H. (2023). Gas exchanges and physiological responses differ among ‘pyrodwarf’ clonal and ‘dargazi’ seedling pear (Pyrus communis L.) rootstocks in response to drought stress. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 23, 6469–6484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-023-01502-1

- 8.*Azizi A, Bagnazari M, & Mohammadi M. (2024). Seaweed and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria biofertilizers ameliorate physiochemical traits and essential oil content of Calendula officinalis L. under drought stress. Scientia Horticulturae, 328, 112653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112653

- 9.

*Bahamonde HA, Aranda I, Peri PL, Gyenge J, & Fernández V. (2023). Leaf wettability, anatomy and ultra-structure of Nothofagus antarctica and N. betuloides grown under a CO2 enriched atmosphere. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 194, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.11.020

- 10.*Bañon S, Fernandez JA, Franco JA, Torrecillas A, Alarcón JJ, & Sánchez-Blanco MJ. (2004). Effects of water stress and night temperature preconditioning on water relations and morphological and anatomical changes of Lotus creticus plants. Scientia Horticulturae, 101, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2003.11.007

- 11.*Barbosa MAM, Chitwood DH, Azevedo AA, Araújo WL, Ribeiro DM, Peres LEP, Martins SCV, & Zsögön A. (2019). Bundle sheath extensions affect leaf structural and physiological plasticity in response to irradiance. Plant, Cell & Environment, 42, 1575–1589. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13495

- 12.

Barclay RS, & Wing SL. (2016). Improving the Ginkgo CO2 barometer: Implications for the early Cenozoic atmosphere. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 439, 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.01.012

- 13.*Baroli I, Price GD, Badger MR, & Von Caemmerer S. (2008). The contribution of photosynthesis to the red light response of stomatal conductance. Plant Physiology, 146, 323–324. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.107.110924

- 14.*Bartieres EMM, Scalon SPQ, Dresch DM, Cardoso EAS, Jesus MV, & Pereira ZV. (2020). Shading as a means of mitigating water deficit in seedlings of Campomanesia xanthocarpa (Mart.) O. Berg. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 48, 234–244. https://doi.org/10.15835/nbha48111720

- 15.

*Beerling DJ, Birks HH, & Woodward FI. (1995). Rapid late‐glacial atmospheric CO2 changes reconstructed from the stomatal density record of fossil leaves. Journal of Quaternary Science, 10, 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3390100407

- 16.

Beerling DJ, & Chaloner WG. (1992). Stomatal density as an indicator of atmospheric CO2 concentration. The Holocene, 2, 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/095968369200200109

- 17.

*Beerling DJ, McElwain JC, & Osborne CP. (1998). Stomatal responses of the ‘living fossil’ Ginkgo biloba L. to changes in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Journal of Experimental Botany, 49, 1603–1607.

- 18.

*Beerling D, & Woodward FI. (1995). Stomatal responses of variegated leaves to CO2 enrichment. Annals of Botany, 75, 507–511. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1995.1052

- 19.Berry JA, Beerling DJ, & Franks PJ. (2010). Stomata: Key players in the earth system, past and present. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 13, 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.013

- 20.

*Berryman CA, Eamus D, & Duff GA. (1994). Stomatal responses to a range of variables in two tropical tree species grown with CO2 enrichment. Journal of Experimental Botany, 45, 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/45.5.539

- 21.Bertolino LT, Caine RS, & Gray JE. (2019). Impact of stomatal density and morphology on water-use efficiency in a changing world. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00225

- 22.*Björkman O, Boardman N, Anderson J, Thorne S, Goodchild D, & Pyliotis N. (1972). Effect of light intensity during growth of Atriplex patula on the capacity of photosynthetic reactions, chloroplast components and structure. Carnegie Institution Year Book, 71, 115–135.

- 23.

*Blackman CJ, Aspinwall MJ, Resco De Dios V, Smith RA, & Tissue DT. (2016). Leaf photosynthetic, economics and hydraulic traits are decoupled among genotypes of a widespread species of eucalypt grown under ambient and elevated CO2. Functional Ecology, 30, 1491–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12661

- 24.*Boetsch J, Chin J, Ling M, & Croxdale J. (1996). Elevated carbon dioxide affects the patterning of subsidiary cells in Tradescantia stomatal complexes. Journal of Experimental Botany, 47, 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/47.7.925

- 25.*Boughalleb F, Abdellaoui R, Ben-Brahim N, & Neffati M. (2014). Anatomical adaptations of Astragalus gombiformis Pomel. Under drought stress. Open Life Sciences, 9(12), 1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11535-014-0353-7

- 26.

*Bray S, & Reid DM. (2002). The effect of salinity and CO2 enrichment on the growth and anatomy of the second trifoliate leaf of Phaseolus vulgaris. Canadian Journal of Botany, 80, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1139/b02-018

- 27.

Brentnall SJ, Beerling DJ, Osborne CP, Harland M, Francis JE, Valdes PJ, & Wittig VE. (2005). Climatic and ecological determinants of leaf lifespan in polar forests of the high CO2 Cretaceous ‘greenhouse’ world. Global Change Biology, 11, 2177–2195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001068.x

- 28.*Brown CE, Mickelbart MV, & Jacobs DF. (2014). Leaf physiology and biomass allocation of backcross hybrid American chestnut (Castanea dentata) seedlings in response to light and water availability. Tree Physiology, 34, 1362–1375. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpu094

- 29.

*Bryant J, Taylor G, & Frehner M. (1998). Photosynthetic acclimation to elevated CO2 is modified by source:sink balance in three component species of chalk grassland swards grown in a free air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) experiment. Plant, Cell & Environment, 21, 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00265.x

- 30.*Buisson D, & Lee DW. (1993). The developmental responses of Papaya leaves to simulated canopy shade. American Journal of Botany, 80, 947–952. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1993.tb15316.x

- 31.Bush RT, Wallace J, Currano ED, Jacobs BF, McInerney FA, Dunn RE, & Tabor NJ. (2017). Cell anatomy and leaf δ13C as proxies for shading and canopy structure in a Miocene forest from Ethiopia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 485, 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.07.015

- 32.*Cai ZQ. (2011). Shade delayed flowering and decreased photosynthesis, growth and yield of Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia volubilis) plants. Industrial Crops and Products, 34, 1235–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.03.021

- 33.*Cai ZQ, Qi X, & Cao K. (2004). Response of stomatal characteristics and its plasticity to different light intensities in leaves of seven tropical woody seedlings. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 15, 201–204.

- 34.*Caine RS, Yin X, Sloan J, Harrison EL, Mohammed U, Fulton T, Biswal AK, Dionora J, Chater CC, Coe RA, Bandyopadhyay A, Murchie EH, Swarup R, Quick WP, & Gray JE. (2019). Rice with reduced stomatal density conserves water and has improved drought tolerance under future climate conditions. New Phytologist, 221, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15344

- 35.*Caldera HIU, De Costa WAJM, Woodward FI, Lake JA, & Ranwala SMW. (2017). Effects of elevated carbon dioxide on stomatal characteristics and carbon isotope ratio of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes originating from an altitudinal gradient. Physiologia Plantarum, 159, 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12486

- 36.*Cameron R. (1970). Light intensity and the growth of Eucalyptus seedlings. I. Ontogenetic variation in E. fastigata. Australian Journal of Botany, 18, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT9700029

- 37.*Carins-Murphy MR, Dow GJ, Jordan GJ, & Brodribb TJ. (2017). Vein density is independent of epidermal cell size in Arabidopsis mutants. Functional Plant Biology, 44, 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP16299

- 38.*Carrión-Tacuri J, Rubio-Casal AE, De Cires A, Figueroa ME, & Castillo JM. (2011). Lantana camara L.: A weed with great light-acclimation capacity. Photosynthetica, 49, 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-011-0039-6

- 39.

*Case AL, Curtis PS, & Snow AA. (1998). Heritable variation in stomatal responses to elevated CO2 in wild radish, Raphanus raphanistrum (Brassicaceae). American Journal of Botany, 85, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.2307/2446313

- 40.*Cavender-Bares J, Sack L, & Savage J. (2007). Atmospheric and soil drought reduce nocturnal conductance in live oaks. Tree Physiology, 27, 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/27.4.611

- 41.

*Cernusak LA, Winter K, Martínez C, Correa E, Aranda J, Garcia M, Jaramillo C, & Turner BL. (2011). Responses of legume versus nonlegume tropical tree seedlings to elevated CO2 concentration. Plant Physiology, 157, 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.111.182436

- 42.

*Ceulemans R, Van Praet L, & Jiang XN. (1995). Effects of CO2 enrichment, leaf position and clone on stomatal index and epidermal cell density in poplar (Populus). New Phytologist, 131, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb03059.x

- 43.

*Chater C, Peng K, Movahedi M, Dunn JA, Walker HJ, Liang YK, McLachlan DH, Casson S, Isner JC, Wilson I, Neill SJ, Hedrich R, Gray JE, & Hetherington AM. (2015). Elevated CO2-induced responses in stomata require ABA and ABA signaling. Current Biology, 25, 2709–2716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.013

- 44.*Chen WL, Yang WJ, Lo HF, & Yeh DM. (2014). Physiology, anatomy, and cell membrane thermostability selection of leafy radish (Raphanus sativus var. oleiformis Pers.) with different tolerance under heat stress. Scientia Horticulturae, 179, 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.10.003

- 45.Christophel DC, & Rowett A. (1996). Leaf and Cuticle Atlas of Australian leafy Lauraceae. Australian Biological Resources Study.

- 46.Ciha AJ, & Brun WA. (1975). Stomatal size and frequency in soybeans. Crop Science, 15, 309–313. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1975.0011183X001500030008x

- 47.*Clauw P, Coppens F, De Beuf K, Dhondt S, Van Daele T, Maleux K, Storme V, Clement L, Gonzalez N, & Inzé D. (2015). Leaf responses to mild drought stress in natural variants of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 167, 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.254284

- 48.

*Clifford SC, Black CR, Roberts JA, Stronach M, Singleton-Jones PR, & Azam-Ali SN. (1995). The effect of elevated atmospheric CO2 and drought on stomatal frequency in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Journal of Experimental Botany, 46, 847–852.

- 49.Cooper CS, & Qualls M. (1967). Morphology and chlorophyll content of shade and sun leaves of two Legumes. Crop Science, 7, 672–673. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1967.0011183X000700060036x

- 50.

*Dahal K, Knowles VL, Plaxton WC, & Hüner NPA. (2014). Enhancement of photosynthetic performance, water use efficiency and grain yield during long-term growth under elevated CO2 in wheat and rye is growth temperature and cultivar dependent. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 106, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.11.015

- 51.*Dengler NG. (1980). Comparative histological basis of sun and shade leaf dimorphism in Helianthus annuus. Canadian Journal of Botany, 58, 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1139/b80-092

- 52.*Doheny-Adams T, Hunt L, Franks PJ, Beerling DJ, & Gray JE. (2012). Genetic manipulation of stomatal density influences stomatal size, plant growth and tolerance to restricted water supply across a growth carbon dioxide gradient. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367, 547–555. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0272

- 53.*Driesen E, De Proft M, & Saeys W. (2023). Drought stress triggers alterations of adaxial and abaxial stomatal development in basil leaves increasing water-use efficiency. Horticulture Research, 10, uhad075. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad075

- 54.

*Driscoll SP, Prins A, Olmos E, Kunert KJ, & Foyer CH. (2006). Specification of adaxial and abaxial stomata, epidermal structure and photosynthesis to CO2 enrichment in maize leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany, 57, 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj030

- 55.*Ducrey M. (1992). Variation in leaf morphology and branching pattern of some tropical rain forest species from Guadeloupe (French West Indies) under semi-controlled light conditions. Annales Des Sciences Forestières, 49, 553–570. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:19920601

- 56.Dunn RE, Strömberg CAE, Madden RH, Kohn MJ, & Carlini AA. (2015). Linked canopy, climate, and faunal change in the Cenozoic of Patagonia. Science, 347, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260947

- 57.

*Eamus D, Berryman CA, & Duff GA. (1993). Assimilation, stomatal conductance, specific leaf area and chlorophyll responses to elevated CO2 of Maranthes corymbosa, a tropical monsoon rain forest species. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 20, 741–755.

- 58.*Eksteen AB, Grzeskowiak V, Jones NB, & Pammenter NW. (2013). Stomatal characteristics of Eucalyptus grandis clonal hybrids in response to water stress. Southern Forests, 75, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.2989/20702620.2013.804310

- 59.*Elmaghalawy RN, & Abdelhakam S. (2022). Light intensity and phenotypic response in two Vicia faba L. varieties. Catrina, 25, 75–82.

- 60.

*Engineer CB, Ghassemian M, Anderson JC, Peck SC, Hu H, & Schroeder JI. (2014). Carbonic anhydrases, EPF2 and a novel protease mediate CO2 control of stomatal development. Nature, 513, 246–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13452

- 61.

*Estiarte M, Peñuelas J, Kimball BA, Idso SB, LaMorte RL, Pinter PJ, Wall GW, & Garcia RL. (1994). Elevated CO2 effects on stomatal density of wheat and sour orange trees. Journal of Experimental Botany, 45, 1665–1668. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/45.11.1665

- 62.*Fan X, Cao X, Zhou H, Hao L, Dong W, He C, Xu M, Wu H, Wang L, Chang Z, & Zheng Y. (2020). Carbon dioxide fertilization effect on plant growth under soil water stress associates with changes in stomatal traits, leaf photosynthesis, and foliar nitrogen of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Environmental and Experimental Botany, 179, 104203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104203

- 63.Fanourakis D, Aliniaeifard S, Sellin A, Giday H, Körner O, Rezaei Nejad A, Delis C, Bouranis D, Koubouris G, Kambourakis E, Nikoloudakis N, & Tsaniklidis G. (2020). Stomatal behavior following mid- or long-term exposure to high relative air humidity: A review. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 153, 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.05.024

- 64.

*Farnsworth EJ, Ellison AM, & Gong WK. (1996). Elevated CO2 alters anatomy, physiology, growth, and reproduction of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle L.). Oecologia, 108, 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00329032

- 65.Fauset S, Gloor MU, Aidar MPM, Freitas HC, Fyllas NM, Marabesi MA, Rochelle ALC, Shenkin A, Vieira SA, & Joly CA. (2017). Tropical forest light regimes in a human‐modified landscape. Ecosphere, 8, e02002. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2002

- 66.Ferguson DK. (1985). The origin of leaf-assemblages—New light on an old problem. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 46, 117–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-6667(85)90041-7

- 67.*Fernández JA, Balenzategui L, Bañón S, & Franco JA. (2006). Induction of drought tolerance by paclobutrazol and irrigation deficit in Phillyrea angustifolia during the nursery period. Scientia Horticulturae, 107, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2005.07.008

- 68.*Fernandez OA, & Mujica B. (1973). Effects of some environmental factors on the differentiation of stomata in Spirodela intermedia W. Koch. Botanical Gazette, 134, 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1086/336689

- 69.

*Ferris R, Nijs I, Behaeghe T, Impens I. (1996). Elevated CO2 and temperature have different effects on leaf anatomy of perennial ryegrass in spring and summer. Annals of Botany, 78, 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1996.0146

- 70.*Ferris R, Long L, Bunn SM, Robinson KM, Bradshaw HD, Rae AM, & Taylor G. (2002). Leaf stomatal and epidermal cell development: Identification of putative quantitative trait loci in relation to elevated carbon dioxide concentration in poplar. Tree Physiology, 22, 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/22.9.633

- 71.

*Ferris R, & Taylor G. (1994). Stomatal characteristics of four native herbs following exposure to elevated CO2. Annals of Botany, 73, 447–453.

- 72.*Fetcher N, Strain BR, & Oberbauer SF. (1983). Effects of light regime on the growth, leaf morphology, and water relations of seedlings of two species of tropical trees. Oecologia, 58, 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00385229

- 73.*Fini A, Ferrini F, Di Ferdinando M, Brunetti C, Giordano C, Gerini F, & Tattini M. (2014). Acclimation to partial shading or full sunlight determines the performance of container-grown Fraxinus ornus to subsequent drought stress. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.05.008

- 74.*Fini A, Ferrini F, Frangi P, Amoroso G, & Giordano C. (2010). Growth, leaf gas exchange and leaf anatomy of three ornamental shrubs grown under different light intensities. European Journal of Horticultural Science, 75, 111–117.

- 75.

*Franks PJ, Leitch IJ, Ruszala EM, Hetherington AM, & Beerling DJ. (2012). Physiological framework for adaptation of stomata to CO2 from glacial to future concentrations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367, 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0270

- 76.

Franks PJ, Royer DL, Beerling DJ, Van De Water PK, Cantrill DJ, Barbour MM, & Berry JA. (2014). New constraints on atmospheric CO2 concentration for the Phanerozoic. Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 4685–4694. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL060457

- 77.*Friend DJC, & Pomeroy ME. (1970). Changes in cell size and number associated with the effects of light intensity and temperature on the leaf morphology of wheat. Canadian Journal of Botany, 48, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1139/b70-011

- 78.*Fu QS, Zhao B, Wang YJ, Ren S, & Guo YD. (2010). Stomatal development and associated photosynthetic performance of capsicum in response to differential light availabilities. Photosynthetica, 48, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-010-0024-5

- 79.

*Gattmann M, McAdam SAM, Birami B, Link R, Nadal-Sala D, Schuldt B, Yakir D, & Ruehr NK. (2023). Anatomical adjustments of the tree hydraulic pathway decrease canopy conductance under long-term elevated CO2. Plant Physiology, 191, 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac482

- 80.*Gay AP, & Hurd RG. (1975). The influence of light on stomatal density in the tomato. New Phytologist, 75, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1975.tb01368.x

- 81.*Gerardin T, Douthe C, Flexas J, & Brendel O. (2018). Shade and drought growth conditions strongly impact dynamic responses of stomata to variations in irradiance in Nicotiana tabacum. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 153, 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.019

- 82.*Ghorbanzadeh P, Aliniaeifard S, Esmaeili M, Mashal M, Azadegan B, & Seif M. (2021). Dependency of growth, water use efficiency, chlorophyll fluorescence, and stomatal characteristics of lettuce plants to light intensity. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 40, 2191–2207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-020-10269-z

- 83.*Ghosh AK, Ichii M, Asanuma K, & Kusutani A. (1996). Optimum and sub-optimal temperature effects on stomata and photosynthesis rate of determinate soybeans. Acta Horticulturae, 440, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1996.440.15

- 84.*Gobbi KF, Garcia R, Ventrella MC, Neto AFG, & Rocha GC. (2011). Área foliar específica e anatomia foliar quantitativa do capim-braquiária e do amendoim-forrageiro submetidos a sombreamento. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 40, 1436–1444. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-35982011000700006

- 85.*Golan T, Müller‐Moulé P, & Niyogi KK. (2006). Photoprotection mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana acclimate to high light by increasing photosynthesis and specific antioxidants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 29, 879–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01467.x

- 86.Graham HV, Patzkowsky ME, Wing SL, Parker GG, Fogel ML, & Freeman KH. (2014). Isotopic characteristics of canopies in simulated leaf assemblages. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 144, 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.08.032

- 87.Greenwood DR. (1991). The Taphonomy of Plant Macrofossils. In The Processes of Fossilisation (pp. 141–169). Belhaven Press.

- 88.*Groen J. (1973) Photosynthesis of Calendula officjnalis L. and Impatiens parviflora DC., as influenced by light intensity during growth and age of leaves and plants. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen; No. 73-8. https://edepot.wur.nl/290507.

- 89.

*Guehl JM, Picon C, Aussenac G, & Gross P. (1994). Interactive effects of elevated CO2 and soil drought on growth and transpiration efficiency and its determinants in two European forest tree species. Tree Physiology, 14, 707–724.

- 90.Gurevitch J, Koricheva J, Nakagawa S, & Stewart G. (2018). Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature, 555, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

- 91.*Habermann E, Contin DR, Afonso LF, Barosela JR, De Pinho Costa KA, Viciedo DO, Groppo M, & Martinez CA. (2022). Future warming will change the chemical composition and leaf blade structure of tropical C3 and C4 forage species depending on soil moisture levels. Science of The Total Environment, 821, 153342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153342

- 92.

*Habermann E, Dias De Oliveira EA, Contin DR, San Martin JAB, Curtarelli L, Gonzalez-Meler MA, & Martinez CA (2019b). Stomatal development and conductance of a tropical forage legume are regulated by elevated [CO2] under moderate warming. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00609

- 93.

*Habermann E, San Martin JAB, Contin DR, Bossan VP, Barboza A, Braga MR, Groppo M, & Martinez CA (2019a). Increasing atmospheric CO2 and canopy temperature induces anatomical and physiological changes in leaves of the C4 forage species Panicum maximum. PLOS ONE, 14, e0212506. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212506

- 94.

*Hager HA, Ryan GD, Kovacs HM, & Newman JA. (2016). Effects of elevated CO2 on photosynthetic traits of native and invasive C3 and C4 grasses. BMC Ecology, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0082-z

- 95.*Hamanishi ET, Thomas BR, & Campbell MM. (2012). Drought induces alterations in the stomatal development program in Populus. Journal of Experimental Botany, 63, 4959–4971.

- 96.

*Han Y, Wang J, Zhang Y, & Wang S. (2023). Effects of regulated deficit irrigation and elevated CO2 concentration on the photosynthetic parameters and stomatal morphology of two maize cultivars. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 42, 2884–2892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10754-7

- 97.*Hanba YT, Kogami H, & Terashima I. (2002). The effect of growth irradiance on leaf anatomy and photosynthesis in Acer species differing in light demand. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25, 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00881.x

- 98.

*Hao L, Chang Z, Lu Y, Tian Y, Zhou H, Wang Y, Liu L, Wang P, Zheng Y, & Wu J. (2023). Drought dampens the positive acclimation responses of leaf photosynthesis to elevated [CO2] by altering stomatal traits, leaf anatomy, and Rubisco gene expression in Pyrus. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 211, 105375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105375

- 99.

*Haworth M, Elliott-Kingston C, & McElwain JC. (2011). The stomatal CO2 proxy does not saturate at high atmospheric CO2 concentrations: Evidence from stomatal index responses of Araucariaceae conifers. Oecologia, 167, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-011-1969-1

- 100.

*Haworth M, Elliott-Kingston C, & McElwain JC. (2013). Co-ordination of physiological and morphological responses of stomata to elevated [CO2] in vascular plants. Oecologia, 171, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2406-9

- 101.*Haworth M, Fitzgerald A, & McElwain JC. (2011). Cycads show no stomatal-density and index response to elevated carbon dioxide and subambient oxygen. Australian Journal of Botany, 59, 630–639. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT11009

- 102.*Haworth M, Killi D, Materassi A, & Raschi A. (2015). Coordination of stomatal physiological behavior and morphology with carbon dioxide determines stomatal control. American Journal of Botany, 102, 677–688. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1400508

- 103.Herman AB, & Spicer RA. (2010). Mid-Cretaceous floras and climate of the Russian high Arctic (Novosibirsk Islands, Northern Yakutiya). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 295, 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.02.034

- 104.

*Herrick JD, Maherali H, & Thomas RB. (2004). Reduced stomatal conductance in sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) sustained over long‐term CO2 enrichment. New Phytologist, 162, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01045.x

- 105.Higgins JA, Kurbatov AV, Spaulding NE, Brook E, Introne DS, Chimiak LM, Yan Y, Mayewski PA, & Bender ML. (2015). Atmospheric composition 1 million years ago from blue ice in the Allan Hills, Antarctica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 6887–6891. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420232112

- 106.

Hönisch B, Royer DL, Breecker DO, Polissar PJ, Bowen GJ, Henehan MJ, Cui Y, Steinthorsdottir M, McElwain JC, Kohn MJ, Pearson A, Phelps SR, Uno KT, Ridgwell A, … Zhang L. (2023). Toward a Cenozoic history of atmospheric CO2. Science, 382, eadi5177. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi5177

- 107.

Hovenden MJ, & Schimanski LJ. (2000). Genotypic differences in growth and stomatal morphology of Southern beech, Nothofagus cunninghamii, exposed to depleted CO2 concentrations. Functional Plant Biology, 27, 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1071/PP99195

- 108.*Hovenden MJ, & Vander Schoor JK. (2006). The response of leaf morphology to irradiance depends on altitude of origin in Nothofagus cunninghamii. New Phytologist, 169, 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01585.x

- 109.*Hronková M, Wiesnerová D, Šimková M, Skůpa P, Dewitte W, Vráblová M, Zažímalová E, & Šantrůček J. (2015). Light-induced STOMAGEN-mediated stomatal development in Arabidopsis leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66, 4621–4630. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv233

- 110.*Hu J, Yang Q-Y., Huang W, Zhang S-B., & Hu H. (2014). Effects of temperature on leaf hydraulic architecture of tobacco plants. Planta, 240, 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-014-2097-z

- 111.

Hu JJ, Xing YW, Turkington R, Jacques FMB, Su T, Huang YJ, & Zhou ZK. (2015). A new positive relationship between pCO2 and stomatal frequency in Quercus guyavifolia (Fagaceae): A potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. Annals of Botany, 115, 777–788. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcv007

- 112.

*Hunt L, Fuksa M, Klem K, Lhotáková Z, Oravec M, Urban O, & Albrechtová J. (2021). Barley genotypes vary in stomatal responsiveness to light and CO2 conditions. Plants, 10, 2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10112533

- 113.

*Israel WK, Watson-Lazowski A, Chen Z-H., & Ghannoum O. (2022). High intrinsic water use efficiency is underpinned by high stomatal aperture and guard cell potassium flux in C3 and C4 grasses grown at glacial CO2 and low light. Journal of Experimental Botany, 73, 1546–1565. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab477

- 114.

*Jacotot A, Marchand C, Gensous S, & Allenbach M. (2018). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 and increased tidal flooding on leaf gas-exchange parameters of two common mangrove species: Avicennia marina and Rhizophora stylosa. Photosynthesis Research, 138, 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-018-0570-4

- 115.*James SA, & Bell DT. (2000). Influence of light availability on leaf structure and growth of two Eucalyptus globulus ssp. Globulus provenances. Tree Physiology, 20, 1007–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/20.15.1007

- 116.

*Jensen NB, Ottosen C-O., Fomsgaard IS, & Zhou R. (2024). Elevated CO2 induce alterations in the hormonal regulation of stomata in drought stressed tomato seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 212, 108762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108762

- 117.*Jin B, Wang L, Wang J, Jiang KZ, Wang Y, Jiang XX, Ni CY, Wang YL, & Teng NJ. (2011). The effect of experimental warming on leaf functional traits, leaf structure and leaf biochemistry in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biology, 11, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-35

- 118.*Jumrani K, & Bhatia VS. (2020). Influence of different light intensities on specific leaf weight, stomatal density photosynthesis and seed yield in soybean. Plant Physiology Reports, 25, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40502-020-00508-6

- 119.*Jumrani K, Bhatia VS, & Pandey GP. (2017). Impact of elevated temperatures on specific leaf weight, stomatal density, photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in soybean. Photosynthesis Research, 131, 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-016-0326-y

- 120.

*Jurik TW, Chabot JF, & Chabot BF. (1982). Effects of light and nutrients on leaf size, CO2 exchange, and anatomy in wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana). Plant Physiology, 70, 1044–1048. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.70.4.1044

- 121.Kaul RB. (1976). Anatomical observations on floating leaves. Aquatic Botany, 2, 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3770(76)90022-X

- 122.*Kebbas S, Lutts S, & Aid F. (2015). Effect of drought stress on the photosynthesis of Acacia tortilis subsp. Raddiana at the young seedling stage. Photosynthetica, 53, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-015-0113-6

- 123.

*Kelly DW, Hicklenton PR, & Reekie EG. (1991). Photosynthetic response of Geranium to elevated CO2 as affected by leaf age and time of CO2 exposure. Canadian Journal of Botany, 69, 2482–2488. https://doi.org/10.1139/b91-308

- 124.Kelly N, Choe D, Meng Q, & Runkle ES. (2020). Promotion of lettuce growth under an increasing daily light integral depends on the combination of the photosynthetic photon flux density and photoperiod. Scientia Horticulturae, 272, 109565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109565

- 125.*Kemp PR, & Cunningham GL. (1981). Light, temperature and salinity effects on growth, leaf anatomy and photosynthesis of Distichlis spicata (L.) Greene. American Journal of Botany, 68, 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1981.tb07794.x

- 126.*Knecht GN, & O’Leary JW. (1972). The effect of light intensity on stomate number and density of Phaseolus vulgaris L. leaves. Botanical Gazette, 133, 132–134. https://doi.org/10.1086/336626

- 127.

Konrad W, Katul G, Roth-Nebelsick A, & Grein M. (2017). A reduced order model to analytically infer atmospheric CO2 concentration from stomatal and climate data. Advances in Water Resources, 104, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2017.03.018

- 128.Konrad W, Roth‐Nebelsick A, & Traiser C. (2023). High productivity at high latitudes? Photosynthesis and leaf ecophysiology in Arctic forests of the Eocene. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 38, e2023PA004685. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023PA004685

- 129.

Körner C. (1988). Does global increase of CO2 alter stomatal density? Flora, 181, 253–257.

- 130.*Kürschner WM., Stulen I, Wagner F, & Kiper PJC. (1998). Comparison of palaeobotanical observations with experimental data on the leaf anatomy of durmast oak [Quercus petraea (Fagaceae)] in response to environmental change. Annals of Botany, 81, 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1998.0605

- 131.

Kürschner WM. (1997). The anatomical diversity of recent and fossil leaves of the durmast oak (Quercus petraea Lieblein/Q. pseudocastanea Goeppert)—Implications for their use as biosensors of palaeoatmospheric CO2 levels. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 96, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-6667(96)00051-6

- 132.Kürschner WM, Kvaček Z, & Dilcher DL. (2008). The impact of Miocene atmospheric carbon dioxide fluctuations on climate and the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(2), 449–453. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708588105

- 133.Lake JA, Quick WP, Beerling DJ, & Woodward FI. (2001). Signals from mature to new leaves. Nature, 411, 154–154. https://doi.org/10.1038/35075660

- 134.

*Lake JA, & Wade RN. (2009). Plant-pathogen interactions and elevated CO2: Morphological changes in favour of pathogens. Journal of Experimental Botany, 60, 3123–3131. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erp147

- 135.

*Lake JA, & Woodward FI. (2008). Response of stomatal numbers to CO2 and humidity: Control by transpiration rate and abscisic acid. New Phytologist, 179, 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02485.x

- 136.

*Lauber W, & Körner C. (1997). In situ stomatal responses to long-term CO2 enrichment in calcareous grassland plants. Acta Oecologica, 18, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1146-609X(97)80008-2

- 137.

*Lawson T, Craigon J, Black CR, Colls JJ, Landon G, & Weyers JDB. (2002). Impact of elevated CO2 and O3 on gas exchange parameters and epidermal characteristics in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Journal of Experimental Botany, 53, 737–746. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/53.369.737

- 138.Lawson T, & Vialet‐Chabrand S. (2019). Speedy stomata, photosynthesis and plant water use efficiency. New Phytologist, 221, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15330

- 139.*Lee DW. (1988). Simulating forest shade to study the developmental ecology of tropical plants: Juvenile growth in three vines in India. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 4, 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400002844

- 140.*Lee DW, Baskaran K, Mansor M, Mohamad H, & Yap SK. (1996). Irradiance and spectral quality affect Asian tropical rain forest tree seedling development. Ecology, 77, 568–580.

- 141.*Lee DW, Oberbauer SF, Krishnapilay B, Mansor M, Mohamad H, & Yap SK. (1997). Effects of irradiance and spectral quality on seedling development of two Southeast Asian Hopea species. Oecologia, 110, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050126

- 142.*Lee SK, Cho JG, Jeong JH, Ryu S, Han JH, & Do GR. (2020). Effect of the elevated temperature on the growth and physiological responses of peach ‘Mihong’ (Prunus persica). Protected Horticulture and Plant Factory, 29, 373–380. https://doi.org/10.12791/KSBEC.2020.29.4.373

- 143.

*Levine LH, Richards JT, & Wheeler RM. (2009). Super-elevated CO2 interferes with stomatal response to ABA and night closure in soybean (Glycine max). Journal of Plant Physiology, 166, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2008.11.006

- 144.*Li C, & Wang K. (2003). Differences in drought responses of three contrasting Eucalyptus microtheca F. Muell. populations. Forest Ecology and Management, 179(1–3), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00552-2

- 145.

*Li F, Gao X, Li C, He H, Siddique KHM, & Zhao X. (2023). Elevated CO2 concentration regulate the stomatal traits of oilseed rape to alleviate the impact of water deficit on physiological properties. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 211, 105355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105355

- 146.

*Li S, Wang X, Liu X, Thompson AJ, & Liu F. (2022). Elevated CO2 and high endogenous ABA level alleviate PEG-induced short-term osmotic stress in tomato plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 194, 104763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104763

- 147.

*Lin J, Jach ME, & Ceulemans R. (2001). Stomatal density and needle anatomy of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) are affected by elevated CO2. New Phytologist, 150, 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00124.x

- 148.

*Liu J, Temme AA, Cornwell WK, Van Logtestijn RSP, Aerts R, & Cornelissen JHC. (2016). Does plant size affect growth responses to water availability at glacial, modern and future CO2 concentrations? Ecological Research, 31, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-015-1330-y

- 149.

*Lodge RJ, Dijkstra P, Drake BG, & Morison JIL. (2001). Stomatal acclimation to increased CO2 concentration in a Florida scrub oak species Quercus myrtifolia Willd. Plant, Cell & Environment, 24, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00659.x

- 150.*Luken JO, Tholemeier TC, Kuddes LM, & Kunkel BA. (1995). Performance, plasticity, and acclimation of the nonindigenous shrub Lonicera maackii (Caprifoliaceae) in contrasting light environments. Canadian Journal of Botany, 73, 1953–1961. https://doi.org/10.1139/b95-208

- 151.

*Luomala E, Laitinen K, Sutinen S, Kellomäki S, & Vapaavuori E. (2005). Stomatal density, anatomy and nutrient concentrations of Scots pine needles are affected by elevated CO2 and temperature. Plant, Cell & Environment, 28, 733–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01319.x

- 152.

*Lv C, Hu Z, Wei J, & Wang Y. (2022). Transgenerational effects of elevated CO2 on rice photosynthesis and grain yield. Plant Molecular Biology, 110, 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-022-01294-5

- 153.

*Madsen E. (1973). Effect of CO2-concentration on the morphological, histological and cytological changes in tomato plants. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, 23, 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015127309435023

- 154.*Maes WH, Achten WMJ, Reubens B, Raes D, Samson R, & Muys B. (2009). Plant–water relationships and growth strategies of Jatropha curcas L. seedlings under different levels of drought stress. Journal of Arid Environments, 73, 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.04.013

- 155.

*Maherali H, Reid CD, Polley HW, Johnson HB, & Jackson RB. (2002). Stomatal acclimation over a subambient to elevated CO2 gradient in a C3/C4 grassland: Stomatal acclimation to CO2 in a C3/C4 grassland. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25, 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00832.x

- 156.

*Malone SR., Mayeux HS, Johnson HB., & Polley HW. (1993). Stomatal density and aperture length in four plant species grown across a subambient CO2 gradient. American Journal of Botany, 80, 1413–1418.

- 157.

*Marchi S, Tognetti R, Vaccari FP, Lanini M, Kaligarič M, Miglietta F, & Raschi A. (2004). Physiological and morphological responses of grassland species to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations in FACE-systems and natural CO2 springs. Functional Plant Biology, 31, 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP03140

- 158.*Marler TE, Schaffer B, & Crane JH. (1994). Developmental light level affects growth, morphology, and leaf physiology of young carambola trees. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 119, 711–718. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.119.4.711

- 159.*Maroco JP, Edwards GE, & Ku MSB. (1999). Photosynthetic acclimation of maize to growth under elevated levels of carbon dioxide. Planta, 210, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004250050660

- 160.*Martins SCV, Galmés J, Cavatte PC, Pereira LF, Ventrella MC, & DaMatta FM. (2014). Understanding the low photosynthetic rates of sun and shade coffee leaves: Bridging the gap on the relative roles of hydraulic, diffusive and biochemical constraints to photosynthesis. PLoS ONE, 9, e95571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095571

- 161.

*Masle J. (2000). The effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on cell division rates, growth patterns, and blade anatomy in young wheat plants are modulated by factors related to leaf position, vernalization, and genotype. Plant Physiology, 122, 1399–1416. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.122.4.1399

- 162.

*Mateus-Rodríguez JF, Lahive F, Hadley P, & Daymond AJ. (2023). Effects of simulated climate change conditions of increased temperature and [CO2] on the early growth and physiology of the tropical tree crop, Theobroma cacao L. Tree Physiology, 43, 2050–2063. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpad116

- 163.McElwain JC, & Chaloner WG. (1996). The fossil cuticle as a skeletal record of environmental change. Palaios, 11, 376. https://doi.org/10.2307/3515247

- 164.McElwain JC, & Steinthorsdottir M. (2017). Paleoecology, ploidy, paleoatmospheric composition, and developmental biology: A review of the multiple uses of fossil stomata. Plant Physiology, 174, 650–664. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00204

- 165.

*McKee M. (2018). Evaluating the Assumptions of Two Methods for Reconstructing Temperature and CO2 from Fossil Leaves [Master of Arts, Wesleyan University]. https://doi.org/10.14418/wes01.2.189

- 166.*Miskin E, & Rasmusson DC. (1970). Frequency and distribution of stomata in barley. Crop Science, 10, 575–578. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1970.0011183X001000050038x

- 167.*Mousseau M, & Enoch HZ. (1989). Carbon dioxide enrichment reduces shoot growth in sweet chestnut seedlings (Castanea sativa Mill.). Plant, Cell & Environment, 12, 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1989.tb01972.x

- 168.

*Moutinho-Pereira J, Gonçalves B, Bacelar E, Cunha JB, Coutinho J, & Correia CM. (2009). Effects of elevated CO2 on grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): Physiological and yield attributes. Vitis, 48, 159–165.

- 169.

*Mozdzer TJ, & Caplan JS. (2018). Complementary responses of morphology and physiology enhance the stand‐scale production of a model invasive species under elevated CO2 and nitrogen. Functional Ecology, 32, 1784–1796. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13106

- 170.*Muhl QE, Toit ESD, & Robbertse PJ. (2011). Moringa oleifera (horseradish tree) leaf adaptation to temperature regimes. International Journal of Agriculture & Biology, 13, 1021–1024.

- 171.*Nautiyal S, Badola HK, Pal M, & Negi DS. (1994). Plant responses to water stress: Changes in growth, dry matter production, stomatal frequency and leaf anatomy. Biologia Plantarum, 36, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02921275

- 172.Niinemets Ü, Keenan TF, & Hallik L. (2015). A worldwide analysis of within‐canopy variations in leaf structural, chemical and physiological traits across plant functional types. New Phytologist, 205, 973–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13096

- 173.*Oberbauer SF, & Strain BR. (1985). Effects of light regime on the growth and physiology of Pentaclethra macroloba (Mimosaceae) in Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 1, 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400000390

- 174.*Oberbauer SF, & Strain BR. (1986). Effects of canopy position and irradiance on the leaf physiology and morphology of Pentaclethra macroloba (Mimosaceae). American Journal of Botany, 73, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1986.tb12054.x

- 175.

*Oberbauer SF, Strain BR, & Fetcher N. (1985). Effect of CO2-enrichment on seedling physiology and growth of two tropical tree species. Physiologia Plantarum, 65, 352–356.

- 176.*O’Carrigan A, Hinde E, Lu N, Xu XQ, Duan H, Huang G, Mak M, Bellotti B, & Chen ZH. (2014). Effects of light irradiance on stomatal regulation and growth of tomato. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 98, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.10.007

- 177.

*Ogaya R, Llorens L, & Peñuelas J. (2011). Density and length of stomatal and epidermal cells in “living fossil” trees grown under elevated CO2 and a polar light regime. Acta Oecologica, 37, 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2011.04.010

- 178.Oh W, & Kim KS. (2010). Temperature and light intensity induce morphological and anatomical changes of leaf petiole and lamina in Cyclamen persicum. Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology, 51, 494–500.

- 179.

*Oksanen E, Riikonen J, Kaakinen S, Holopainen T, & Vapaavuori E. (2005). Structural characteristics and chemical composition of birch (Betula pendula) leaves are modified by increasing CO2 and ozone. Global Change Biology, 11, 732–748.

- 180.

*O’Leary JW, & Knecht GN. (1981). Elevated CO2 concentration increases stomate numbers in Phaseolus vulgaris leaves. Botanical Gazette, 142, 438–441. https://doi.org/10.1086/337244

- 181.*Onwueme IC, & Johnston M. (2000). Influence of shade on stomatal density, leaf size and other leaf characteristics in the major tropical root crops, tannia, sweet potato, yam, cassava and taro. Experimental Agriculture, 36, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479700001071

- 182.

*Pandey R, Chacko PM, Choudhary ML, Prasad KV, & Pal M. (2007). Higher than optimum temperature under CO2 enrichment influences stomata anatomical characters in rose (Rosa hybrida). Scientia Horticulturae, 113, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2007.01.021

- 183.*Pandey S, Kumar S, & Nagar PK. (2003). Photosynthetic performance of Ginkgo biloba L. grown under high and low irradiance. Photosynthetica, 41, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHOT.0000027514.56808.35

- 184.*Peet MM, Ozbun JL, & Wallace DH. (1977). Physiological and anatomical effects of growth temperature on Phaseolus vulgaris L. cultivars. Journal of Experimental Botany, 28, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/28.1.57

- 185.*Pérez-Bueno ML, Illescas-Miranda J, Martín-Forero AF, De Marcos A, Barón M, Fenoll C, & Mena M. (2022). An extremely low stomatal density mutant overcomes cooling limitations at supra-optimal temperature by adjusting stomatal size and leaf thickness. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 919299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.919299

- 186.*Phunthong C, Pitaloka MK, Chutteang C, Ruengphayak S, Arikit S, & Vanavichit A. (2024). Rice mutants, selected under severe drought stress, show reduced stomatal density and improved water use efficiency under restricted water conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 15, 1307653. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1307653

- 187.*Pilarski J, & Bethenod O. (1985). Acclimatation à la temperature de la photosynthese du tournesol (Helianthus anuus L.). Photosynthetica, 19, 25–36.

- 188.*Pompelli MF, Martins SCV, Celin EF, Ventrella MC, & DaMatta FM. (2010). What is the influence of ordinary epidermal cells and stomata on the leaf plasticity of coffee plants grown under full-sun and shady conditions? Brazilian Journal of Biology, 70, 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842010000500025

- 189.*Pons TL. (1977). An ecophysiological study in the field layer of ash coppice. II. Experiments with Geum urbanum and Cirsium palustre in different light intensities. Acta Botanica Neerlandica, 26, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.1977.tb01093.x

- 190.

*Poole I, Lawson T, Weyers JDB, & Raven JA. (2000). Effect of elevated CO2 on the stomatal distribution and leaf physiology of Alnus glutinosa. New Phytologist, 145, 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00589.x

- 191.Poole I, Weyers JDB, Lawson T, & Raven JA. (1996). Variations in stomatal density and index: Implications for palaeoclimatic reconstructions. Plant, Cell & Environment, 19, 705–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00405.x

- 192.

Poorter H, Knopf O, Wright IJ, Temme AA, Hogewoning SW, Graf A, Cernusak LA, & Pons TL (2022a). A meta‐analysis of responses of C3 plants to atmospheric CO2: Dose–response curves for 85 traits ranging from the molecular to the whole‐plant level. New Phytologist, 233, 1560–1596. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17802

- 193.Poorter H, Niinemets Ü, Ntagkas N, Siebenkäs A, Mäenpää M, Matsubara S, & Pons TL. (2019). A meta‐analysis of plant responses to light intensity for 70 traits ranging from molecules to whole plant performance. New Phytologist, 223, 1073–1105. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15754

- 194.Poorter H, Yin X, Alyami N, Gibon Y, & Pons TL (2022b). MetaPhenomics: Quantifying the many ways plants respond to their abiotic environment, using light intensity as an example. Plant and Soil, 476, 421–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-022-05391-8

- 195.

*Porter AS, Evans-Fitz.Gerald C, Yiotis C, Montañez IP, & McElwain JC. (2019). Testing the accuracy of new paleoatmospheric CO2 proxies based on plant stable carbon isotopic composition and stomatal traits in a range of simulated paleoatmospheric O2:CO2 ratios. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 259, 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.05.037

- 196.

*Quirk J, Bellasio C, Johnson DA, & Beerling DJ. (2019). Response of photosynthesis, growth and water relations of a savannah-adapted tree and grass grown across high to low CO2. Annals of Botany, 124, 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcz048

- 197.*Quirk J, McDowell NG, Leake JR, Hudson PJ, & Beerling DJ. (2013). Increased susceptibility to drought‐induced mortality in Sequoia sempervirens (Cupressaceae) trees under Cenozoic atmospheric carbon dioxide starvation. American Journal of Botany, 100, 582–591. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1200435

- 198.

*Radoglou KM, & Jarvis PG. (1990). Effects of CO2 enrichment on four poplar clones. II. Leaf surface properties. Annals of Botany, 65, 627–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087979

- 199.Rahim MA, & Fordham R. (1991). Effect of shade on leaf and cell size and number of epidermal cells in garlic. Annals of Botany, 67, 167–171.

- 200.

*Radoglou KM, & Jarvis PG. (1992). The effects of CO2 enrichment and nutrient supply on growth morphology and anatomy of Phaseolus vulgaris L. seedlings. Annals of Botany, 70, 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088466

- 201.*Rawson H, Gardner P, & Long M. (1987). Sources of variation in specific leaf area in wheat grown at high temperature. Functional Plant Biology, 14, 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1071/PP9870287

- 202.

*Reddy KR, Robana RR, Hodges HF, Liu XJ, & McKinion JM. (1998). Interactions of CO2 enrichment and temperature on cotton growth and leaf characteristics. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 39, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0098-8472(97)00028-2

- 203.

Reichgelt T, D’Andrea WJ, Valdivia-McCarthy AC, Fox BRS., Bannister JM, Conran JG, Lee WG, & Lee DE. (2020). Elevated CO2, increased leaf-level productivity, and water-use efficiency during the early Miocene. Climate of the Past, 16, 1509–1521. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-16-1509-2020

- 204.

Reid CD, Maherali H, Johnson HB, Smith SD, Wullschleger SD, & Jackson RB. (2003). On the relationship between stomatal characters and atmospheric CO2. Geophysical Research Letters, 30, 2003GL017775. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017775

- 205.*Retuerto R, Lema BF, Roiloa SR, & Obeso JR. (2000). Gender, light and water effects in carbon isotope discrimination, and growth rates in the dioecious tree Ilex aquifolium. Functional Ecology, 14, 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2000.t01-1-00454.x

- 206.

*Rey A, & Jarvis PG. (1997). Growth response of young birch trees (Betula pendula Roth.) after four and a half years of CO2 exposure. Annals of Botany, 80, 809–816. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0526

- 207.

*Rico C, Pittermann J, Polley HW, Aspinwall MJ, & Fay PA. (2013). The effect of subambient to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on vascular function in Helianthus annuus: Implications for plant response to climate change. New Phytologist, 199, 956–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12339

- 208.

*Riikonen J, Percy KE, Kivimäenpää M, Kubiske ME, Nelson ND, Vapaavuori E, & Karnosky DF. (2010). Leaf size and surface characteristics of Betula papyrifera exposed to elevated CO2 and O3. Environmental Pollution, 158, 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2009.07.034

- 209.*Ro HM, Kim PG, Lee IB, Yiem MS, & Woo SY. (2001). Photosynthetic characteristics and growth responses of dwarf apple (Malus domestica Borkh. Cv. Fuji) saplings after 3 years of exposure to elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration and temperature. Trees, 15, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004680100099

- 210.

Roth-Nebelsick A. (2005). Reconstructing atmospheric carbon dioxide with stomata: Possibilities and limitations of a botanical pCO2-sensor. Trees, 19, 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-004-0375-2

- 211.

*Rowland-Bamford AJ, Nordenbrock C, Baker JT, Bowes G, & Hartwell Allen L. (1990). Changes in stomatal density in rice grown under various CO2 regimes with natural solar irradiance. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 30, 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0098-8472(90)90062-9

- 212.

Royer DL. (2001). Stomatal density and stomatal index as indicators of paleoatmospheric CO2 concentration. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 114, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-6667(00)00074-9

- 213.

Royer DL. (2003). Estimating latest Cretaceous and Tertiary atmospheric CO2 from stomatal indices. In Causes and Consequences of Globally Warm Climates in the Early Paleogene (pp. 79–93). Geological Society of America.

- 214.

Rundgren M, & Beerling D. (1999). A Holocene CO2 record from the stomatal index of subfossil Salix herbacea L. leaves from northern Sweden. The Holocene, 9, 509–513. https://doi.org/10.1191/095968399677717287

- 215.*Ryu D, Bae J, Park J, Cho S, Moon M, Oh CY., & Kim H. (2014). Responses of native trees species in Korea under elevated carbon dioxide condition—Open top chamber experiment. Korean Journal of Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 16, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.5532/KJAFM.2014.16.3.199

- 216.Salisbury EJ. (1927). On the causes and ecological significance of stomatal frequency, with special reference to the woodland flora. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 216, 431–439.

- 217.*Sánchez-Virosta A, & Sánchez-Gómez D. (2019). Inter-cultivar variability in the functional and biomass response of garlic (Allium sativum L.) to water availability. Scientia Horticulturae, 252, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.03.043

- 218.

Šantrůček J, Vráblová M, Šimková M, Hronková M, Drtinová M, Květoň J, Vrábl D, Kubásek J, Macková J, Wiesnerová D, Neuwithová J, & Schreiber L. (2014). Stomatal and pavement cell density linked to leaf internal CO2 concentration. Annals of Botany, 114, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcu095

- 219.*Scarr MJ. (2011). The use of stomatal frequency from three Australian evergreen tree species as a proxy indicator of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration [Doctoral thesis, Victoria University]. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/16044/1/Mark_Scarr_thesis_2011.pdf

- 220.*Schlüter U, Muschak M, Berger D, & Altmann T. (2003). Photosynthetic performance of an Arabidopsis mutant with elevated stomatal density (sdd1-1) under different light regimes. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54, 867–874. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg087

- 221.*Schoch P. (1972). Effects of shading on structural characteristics of the leaf and yield of fruit in Capsicum annuum L. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 97, 461–464.

- 222.*Schoch P, & Candelario LS. (1974). Influencia de la sombra sobre el crecimiento y la productividad de las hojas de Vigna sinensis L. Turrialba, 3, 84–89.

- 223.*Schoch P, Lecharny A, & Zinsou C. (1977). Influence de l’eclairement et de la temperature sur l’indice stomatique des feuilles du Vigna sinensis L. Comptes Rendus Academie Sciences Paris, 285, 673–675.

- 224.*Schoch P, & Zinsou C. (1975). Effet de L’ombrage sur la formation des stomates de quatre varietes deVigna sinensis L. Oecologia Plantarum, 10, 195–199.

- 225.*Schoch P, Zinsou C, & Sibi M. (1980). Dependence of the stomatal index on environmental factors during stomatal differentiation in leaves of Vigna sinensis L. 1. Effect of light intensity. Journal of Experimental Botany, 31, 1211–1216.

- 226.*Schürmann B. (1959). Über den Einfluß der Hydratur und des Lichtes auf die Ausbildung der Stomata-Initialen. Flora, 147(4), 471–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0367-1615(17)31981-X

- 227.

*Sekiya N, & Yano K. (2008). Stomatal density of cowpea correlates with carbon isotope discrimination in different phosphorus, water and CO2 environments. New Phytologist, 179, 799–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02518.x

- 228.*Šesták Z, Solárová J, Zima J, & Václavák J. (1978). Effect of growth irradiance on photosynthesis and transpiration in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Biologia Plantarum, 20(3), 234–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02923637

- 229.*Shekari F, Soltaniband V, Javanmard A, & Abbasi A. (2015). The impact of drought stress at different stages of development on water relations, stomatal density and quality changes of rapeseed. Iran Agricultural Research, 34, 81–90.

- 230.

*Singh SK, Badgujar G, Reddy VR, Fleisher DH, & Bunce JA. (2013). Carbon dioxide diffusion across stomata and mesophyll and photo-biochemical processes as affected by growth CO2 and phosphorus nutrition in cotton. Journal of Plant Physiology, 170, 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2013.01.001

- 231.*Smith M, & Martin CE. (1987). Growth and morphological responses to irradiance in three forest understory species of the C4 grass genus Muhlenbergia. Botanical Gazette, 148, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1086/337641

- 232.

*Smith RA, Lewis JD, Ghannoum O, & Tissue DT. (2012). Leaf structural responses to pre-industrial, current and elevated atmospheric [CO2] and temperature affect leaf function in Eucalyptus sideroxylon. Functional Plant Biology, 39, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP11238

- 233.

*Soares AS, Driscoll SP, Olmos E, Harbinson J, Arrabaça MC, & Foyer CH. (2008). Adaxial/abaxial specification in the regulation of photosynthesis and stomatal opening with respect to light orientation and growth with CO2 enrichment in the C4 species Paspalum dilatatum. New Phytologist, 177, 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02218.x

- 234.Stephens GL. (2005). Cloud feedbacks in the climate system: A critical review. Journal of Climate, 18, 237–273. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-3243.1

- 235.*Stewart JD, & Hoddinott J. (1993). Photosynthetic acclimation to elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide and UV irradiation in Pinus banksiana. Physiologia Plantarum, 88, 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb01364.x

- 236.*Sui X, Mao S, Wang L, Li W, Zhang B, & Zhang Z. (2009). Response of anatomical structure and photosynthetic characteristics to low light in leaves of Capsicum seedlings. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 36, 195–208.

- 237.*Sun Y, Yan F, Cui X, & Liu F. (2014). Plasticity in stomatal size and density of potato leaves under different irrigation and phosphorus regimes. Journal of Plant Physiology, 171, 1248–1255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2014.06.002

- 238.

*Temme AA, Liu JC, Van Hal J, Cornwell WK, Cornelissen J (Hans) HC, & Aerts R. (2017). Increases in CO2 from past low to future high levels result in “slower” strategies on the leaf economic spectrum. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 29, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2017.11.003

- 239.

*Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, & Lin J. (2006). Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist, 172, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01818.x

- 240.

*Thinh NC, Kumagai E, Shimono H, & Kawasaki M. (2018). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on morphology of leaf blades in Chinese yam. Plant Production Science, 21, 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/1343943X.2018.1511377

- 241.*Thiraporn R, & Geisler G. (1978). Untersuchungen zur Entwicklung Morphologischer und Anatomischer Merkmale von Maisinzuchtlinien in Abhängigkeit von der Temperatur. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 147, 300–308.

- 242.

*Thomas JF, & Harvey CN. (1983). Leaf anatomy of four species grown under continuous CO2 enrichment. Botanical Gazette, 144, 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1086/337377

- 243.Thomas PW, Woodward FI, & Quick WP. (2004). Systemic irradiance signalling in tobacco. New Phytologist, 161, 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00954.x

- 244.

*Tipping C, & Murray DR. (1999). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on leaf anatomy and morphology in Panicum species representing different photosynthetic modes. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 160, 1063–1073. https://doi.org/10.1086/314201

- 245.

*Tocquin P, Ormenese S, Pieltain A, Detry N, Bernier G, & Périlleux C. (2006). Acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana to long‐term CO2 enrichment and nitrogen supply is basically a matter of growth rate adjustment. Physiologia Plantarum, 128, 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00791.x

- 246.

*Tricker PJ, Trewin H, Kull O, Clarkson GJJ, Eensalu E, Tallis MJ, Colella A, Doncaster CP, Sabatti M, & Taylor G. (2005). Stomatal conductance and not stomatal density determines the long-term reduction in leaf transpiration of poplar in elevated CO2. Oecologia, 143, 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-005-0025-4

- 247.

*Tuba Z, Szente K, & Koch J. (1994). Response of photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, water use efficiency and production to long-term elevated CO2 in winter wheat. Journal of Plant Physiology, 144, 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-1617(11)80657-7

- 248.*Uprety DC, Dwivedi N, Jain V, & Mohan R. (2002). Effect of elevated carbon dioxide concentration on the stomatal parameters of rice cultivars. Photosynthetica, 40, 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021322513770

- 249.*Valladares F, Chico J, Aranda I, Balaguer L, Dizengremel P, Manrique E, & Dreyer E. (2002). The greater seedling high-light tolerance of Quercus robur over Fagus sylvatica is linked to a greater physiological plasticity. Trees, 16, 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-002-0184-4

- 250.

*Vanhatalo M, Huttunen S, & Bäck J. (2001). Effects of elevated [CO2] and O3 on stomatal and surface wax characteristics in leaves of pubescent birch grown under field conditions. Trees, 15, 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004680100105

- 251.

*Visser AJ, Tosserams M, Groen MW, Kalis G, Kwant R, Magendans GWH, & Rozema J. (1997). The combined effects of CO2 concentration and enhanced UV-B radiation on faba bean. 3. Leaf optical properties, pigments, stomatal index and epidermal cell density. Plant Ecology, 128, 209–222.

- 252.Vráblová M, Hronková M, Vrábl D, Kubásek J, & Šantrůček J. (2018). Light intensity-regulated stomatal development in three generations of Lepidium sativum. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 156, 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.09.012

- 253.

*Vuorinen T, Nerg A-M., Ibrahim MA, Reddy GVP, & Holopainen JK. (2004). Emission of Plutella xylostella-induced compounds from cabbages grown at elevated CO2 and orientation behavior of the natural enemies. Plant Physiology, 135, 1984–1992. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.104.047084

- 254.

Wall S, Cockram J, Vialet-Chabrand S, Van Rie J, Gallé A, & Lawson T. (2023). The impact of growth at elevated [CO2] on stomatal anatomy and behavior differs between wheat species and cultivars. Journal of Experimental Botany, 74, 2860–2874. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erad011

- 255.Wang J-H., Cai Y-F., Li S-F., & Zhang S-B. (2020b). Photosynthetic acclimation of rhododendrons to light intensity in relation to leaf water-related traits. Plant Ecology, 221, 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-020-01019-y

- 256.

*Wang LL, Li YY, Li XM, Ma LJ, & He XY. (2019). Co-ordination of photosynthesis and stomatal responses of mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica Fisch. Ex Ledeb.) to elevated O3 and/or CO2 levels. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 17, 4257–4268. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1702_42574268

- 257.

*Wang N, Gao G, Wang Y, Wang D, Wang Z, & Gu J (2020a). Coordinated responses of leaf and absorptive root traits under elevated CO2 concentration in temperate woody and herbaceous species. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 179, 104199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104199

- 258.Wang X, Wei X, Wu G, & Chen S (2020c). High nitrate or ammonium applications alleviated photosynthetic decline of Phoebe bournei seedlings under elevated carbon dioxide. Forests, 11, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11030293

- 259.*Wang X, Wei X, Wu G, & Chen S. (2021). Ammonium application mitigates the effects of elevated carbon dioxide on the carbon/nitrogen balance of Phoebe bournei seedlings. Tree Physiology, 41, 1658–1668. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpab026

- 260.

*Wei Z, Abdelhakim LOA, Fang L, Peng X, Liu J, & Liu F. (2022). Elevated CO2 effect on the response of stomatal control and water use efficiency in amaranth and maize plants to progressive drought stress. Agricultural Water Management, 266, 107609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107609

- 261.*Wentworth M, Murchie EH, Gray JE, Villegas D, Pastenes C, Pinto M, & Horton P. (2006). Differential adaptation of two varieties of common bean to abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Botany, 57, 699–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj061

- 262.West CK, Greenwood DR, & Basinger JF. (2019). The late Paleocene to early Eocene Arctic megaflora of Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg islands, Nunavut, Canada. Palaeontographica Abteilung B, 300, 47–163. https://doi.org/10.1127/palb/2019/0066

- 263.*Wiebel J, Chacko EK, Downton WJS, & Ludders P. (1994). Influence of irradiance on photosynthesis, morphology and growth of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) seedlings. Tree Physiology, 14, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/14.3.263

- 264.*Wild A, & Wolf G. (1980). The effect of different light intensities on the frequency and size of stomata, the size of cells, the number, size and chlorophyll content of chloroplasts in the mesophyll and the guard cells during the ontogeny of primary leaves of Sinapis alba. Zeitschrift Für Pflanzenphysiologie, 97, 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-328X(80)80006-7

- 265.

*Will RE, & Teskey RO. (1997). Effect of irradiance and vapour pressure deficit on stomatal response to CO2 enrichment of four tree species. Journal of Experimental Botany, 48, 2095–2102. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/48.12.2095

- 266.

Wolfe AP, Reyes AV, Royer DL, Greenwood DR, Doria G, Gagen MH, Siver PA, & Westgate JA. (2017). Middle Eocene CO2 and climate reconstructed from the sediment fill of a subarctic kimberlite maar. Geology, 45, 619–622. https://doi.org/10.1130/G39002.1

- 267.

Woodward FI. (1987). Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature, 327, 617–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/327617a0

- 268.

Woodward FI. (1993). Plant responses to past concentrations of CO2. Vegetatio, 104/105, 145–155.

- 269.

*Woodward FI, & Bazzaz FA. (1988). The responses of stomatal density to CO2 partial pressure. Journal of Experimental Botany, 39, 1771–1781. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/39.12.1771

- 270.*Worku W, Skjelvåg AO, & Gislerød HR. (2004). Responses of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) to photosynthetic irradiance levels during three phenological phases. Agronomie, 24, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2004024

- 271.*Wu YP, Hu XW, & Wang YR. (2009). Growth, water relations, and stomatal development of Caragana korshinskii Kom. And Zygophyllum xanthoxylum (Bunge) Maxim. seedlings in response to water deficits. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 52, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230909510503

- 272.

*Xu D, Terashima K, Crang R, Chen X, & Hesketh J. (1994). Stomatal and nonstomatal acclimation to a CO2-enriched atmosphere. Biotronics, 23, 1–9.

- 273.

*Xu M. (2015). The optimal atmospheric CO2 concentration for the growth of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Journal of Plant Physiology, 184, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.07.003

- 274.*Xu Z, & Zhou G. (2008). Responses of leaf stomatal density to water status and its relationship with photosynthesis in a grass. Journal of Experimental Botany, 59, 3317–3325. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ern185

- 275.*Xu ZZ, & Zhou GS. (2005). Effects of water stress and high nocturnal temperature on photosynthesis and nitrogen level of a perennial grass Leymus chinensis. Plant and Soil, 269, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-004-0397-y

- 276.Yan W, Zhong Y, & Shangguan Z. (2017). Contrasting responses of leaf stomatal characteristics to climate change: A considerable challenge to predict carbon and water cycles. Global Change Biology, 23, 3781–3793. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13654

- 277.*Yang D, Peng S, & Wang F. (2020). Response of photosynthesis to high growth temperature was not related to leaf anatomy plasticity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 26. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00026

- 278.

Yang K, Huang Y, Yang J, Lv C, Hu Z, Yu L, & Sun W. (2023). Effects of three patterns of elevated CO2 in single and multiple generations on photosynthesis and stomatal features in rice. Annals of Botany, 131, 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcad021

- 279.Ydenberg R, Leyland B, Hipfner M, & Prins HHT. (2021). Century‐long stomatal density record of the nitrophyte, Rubus spectabilis L., from the Pacific Northwest indicates no effect of changing atmospheric carbon dioxide but a strong response to nutrient subsidy. Ecology and Evolution, 11, 18081–18088. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8405

- 280.

*Yi Y, Sugiura D, & Yano K. (2019). Quantifying phosphorus and water demand to attain maximum growth of Solanum tuberosum in a CO2-enriched environment. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 1417. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01417

- 281.

*Yi Y, Sugiura D, & Yano K. (2020). Nitrogen and water demands for maximum growth of Solanum tuberosum under doubled CO2: Interaction with phosphorus based on the demands. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 176, 104089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104089

- 282.*Zanewich KP, Pearce DW, & Rood SB. (2018). Heterosis in poplar involves phenotypic stability: Cottonwood hybrids outperform their parental species at suboptimal temperatures. Tree Physiology, 38, 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpy019

- 283.*Zanewich KP, & Rood SB. (2023). Limited sex differentiation in poplars: Similar physiological responses to low temperature of males and females of three cottonwood taxa. Trees, 37, 1217–1223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-023-02421-5

- 284.*Zhang LX, Guo QS, Chang QS, Zhu ZB, Liu L, & Chen YH. (2015). Chloroplast ultrastructure, photosynthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in Glechoma longituba in response to irradiance. Photosynthetica, 53, 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-015-0092-7

- 285.

*Zhang M, Wei G, Cui B, Liu C, Wan H, Hou J, Chen Y, Zhang J, Liu J, & Wei Z. (2024). CO2 elevation and N fertilizer supply modulate leaf physiology, crop growth and water use efficiency of maize in response to progressive soil drought. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 210, e12692. https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.12692

- 286.

*Zhao Y, Sun M, Guo H, Feng C, Liu Z, & Xu J. (2022). Responses of leaf hydraulic traits of Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani to increasing temperature and CO2 concentrations. Botanical Studies, 63, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-022-00331-2

- 287.*Zheng L, & Van Labeke M. (2018). Effects of different irradiation levels of light quality on Chrysanthemum. Scientia Horticulturae, 233, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.01.033

- 288.

*Zheng Y, He C, Guo L, Hao L, Cheng D, Li F, Peng Z, & Xu M. (2020). Soil water status triggers CO2 fertilization effect on the growth of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 291, 108097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.108097

- 289.

*Zheng Y, Li F, Hao L, Yu J, Guo L, Zhou H, Ma C, Zhang X, & Xu M. (2019). Elevated CO2 concentration induces photosynthetic down-regulation with changes in leaf structure, non-structural carbohydrates and nitrogen content of soybean. BMC Plant Biology, 19, 255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1788-9

- 290.*Zheng Y, Xu M, Hou R, Shen R, Qiu S, & Ouyang Z. (2013). Effects of experimental warming on stomatal traits in leaves of maize (Zea mays). Ecology and Evolution, 3, 3095–3111. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.674

- 291.*Zhou SB, Liu K, Zhang D, Li QF, & Zhu GP. (2010). Photosynthetic performance of Lycoris radiata var. Radiata to shade treatments. Photosynthetica, 48, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-010-0030-7

- 292.*Zhu Y, Huang L, Dang C, Wang H, Jiang G, Li G, Zhang Z, Lou X, & Zheng Y. (2016). Effects of high temperature on leaf stomatal traits and gas exchange parameters of blueberry. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 32, 218–225.

- 293.*Zinsou C, & Schoch P. (1979). Mise en evidence de la participation des feuilles adultes à l’expression de I’indice stomatique de la jeune feuille en differenciation du Vigna sinensis L. Physiologie Végetale, 17, 327–336.

- 294.*Zoulias N, Brown J, Rowe J, & Casson SA. (2020). HY5 is not integral to light mediated stomatal development in Arabidopsis. PLOS ONE, 15, e0222480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222480

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.