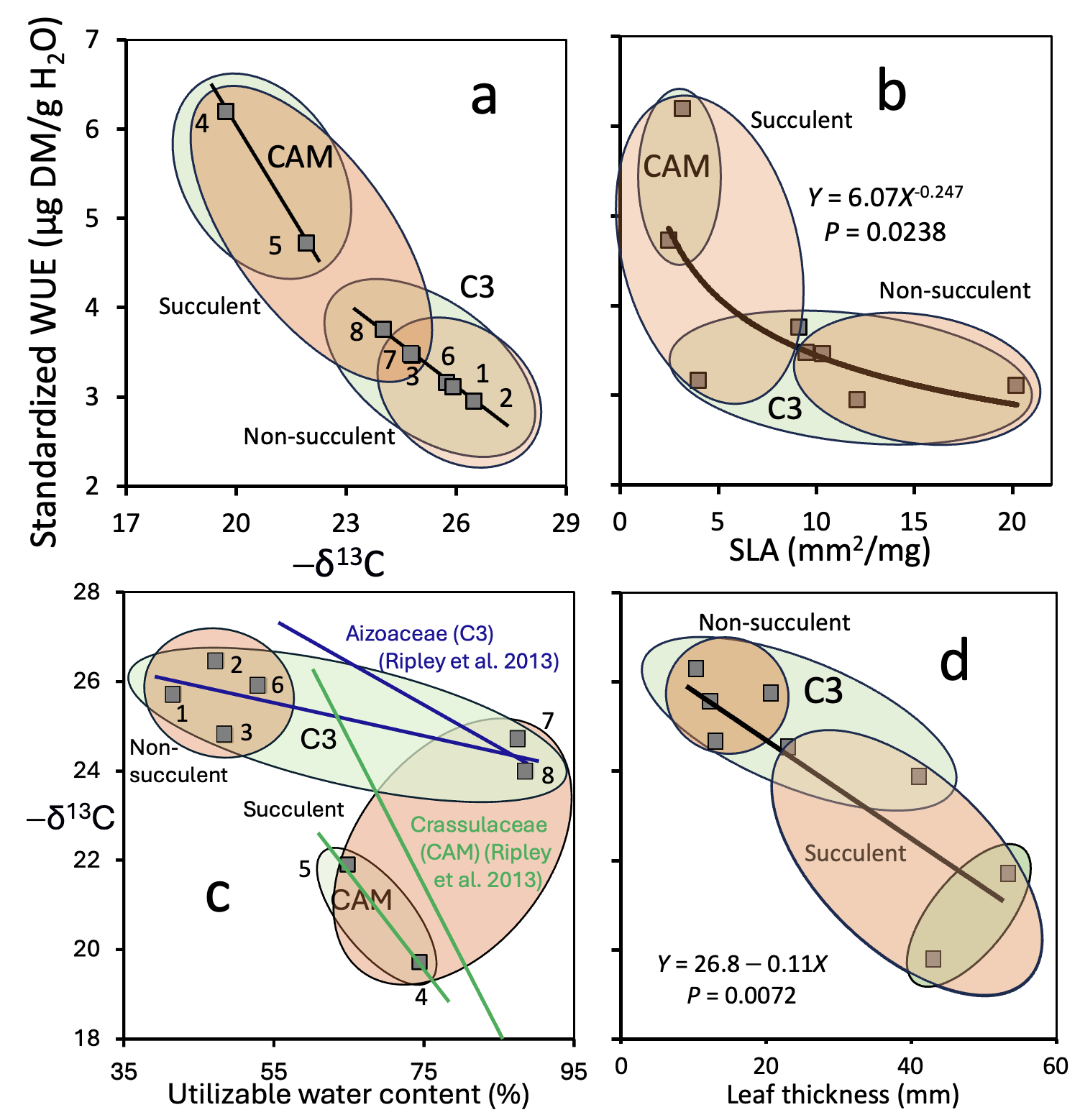

Shrubs (families Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Aizoaceae and Zygophyllaceae) in the succulent karoo of the southern Namib Desert survive an annual rainfall < 150 mm per annum but vary greatly in their vegetative morphology, so we hypothesised that they must possess a range of structural and physiological traits to resist perennial drought. Eight Namib species were assessed for their leaf structural properties [e.g., thickness (z), specific leaf area (SLA)], water storage capacity [e.g., relative water content (RWC)] and water potential (ψ) over 12 months or when severed from the parent plant in the field and laboratory, water-use efficiency (WUE) via δ13C content, and metabolite (N, P) and osmotic ion (Na+, K+) contents. Four species were considered (1) orthophylls/semi-succulents, and (2) four were succulents (succophylls), (3), two of these exhibiting CAM-type photosynthesis, and (4) six with C3-type photosynthesis. Succophylls were distinguished by their thicker leaves, lower SLA, presence of water-storing parenchyma, higher levels of ‘utilizable’ water, slower rates of water loss, higher/less variable ψ, and higher (Na+ + K+), N and P contents/leaf-area, δ13C and WUE. Water-loss resistance (WLR)—the change in RWC resulting from a given change in water potential (ΔRWC/Δψ) when subjected to drought conditions—was twice as high in the succophylls as the non-succulents under both laboratory and field conditions, with the latter showing twice the level of osmotic adjustment for a given drop in RWC. Leaves of the CAM species stored most water, decreased their ψ overnight, showed least rates of water loss, and had the highest N/P contents/area and WUE. Cations may serve an osmotic balancing function among succophylls, whereas high N and P/area may help maintain metabolic functions when transpiration is limited. δ13C/WUE relationships were functions of photosynthetic type, N/P contents/area, and (especially) leaf thickness. The opposing water relations of the four groups centre around their different trait combinations for accessing, utilizing and storing water. The special structural and physiological properties of succophylls need to be recognized when developing any general theory about the water relations of plants.

- Open Access

- Article

Leaf Thickness as Key to the Contrasting Water and Nutrient Relations of Eight Arid-Climate Species, Including Water-Loss Resistance

Author Information

Received: 22 Mar 2025 | Revised: 13 Aug 2025 | Accepted: 18 Aug 2025 | Published: 20 Aug 2025

Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

leaf succulents | nitrogen and phosphorus contents | saturated leaf water content | SLA | water potential | water-use efficiency

References

- 1.Blackman CJ, & Brodribb TJ. (2011). Two measures of leaf capacitance: Insights into the water transport pathway and hydraulic conductance in leaves. Functional Plant Biology, 38(2), 118–126.

- 2.Borland AM, Griffiths H, Hartwell J, & Smith JAC. (2009). Exploiting the potential of plants with crassulacean acid metabolism for bioenergy production on marginal lands. Journal of Experimental Botany, 60(10), 2879–2896.

- 3.Bowie MRA. (1999). Ecophysiological Studies on Four Selected Succulent Karoo Species. Master’s Thesis. University of Stellenbosch.

- 4.Buckley TN. (2017). Modeling stomatal conductance. Plant Physiology, 174, 572–582.

- 5.Cicuzza D, Stäheli D, Nyffeler R, & Eggli U. (2018). Morphology and anatomy support a reclassification of the African succulent taxa of Senecio sl (Asteraceae: Senecioeae). Haseltonia, 2017, 11–26.

- 6.Cowling RM, & Campbell BM. (1983). The definition of leaf consistence in the fynbos biome and their distribution along an altitudinal gradient in the southeastern Cape. Journal of South African Botany, 49, 87–101.

- 7.Delf EM. (1911). Transpiration and behaviour of stomata in halophytes. Annals of Botany, 25, 485e505.

- 8.Eccles NS, Esler KJ, & Cowling RM. (1999). Spatial pattern analysis in Namaqualand desert plant communities: Evidence for general positive interactions. Plant Ecology, 142, 71–85.

- 9.Eccles NS, Lamont BB, Esler KJ, & Lamont HC. (2001). Relative performance of clumped vs. experimentally isolated plants in a South African winter-rainfall desert community. Plant Ecology, 155, 219–227.

- 10.Ehleringer JR, & Osmond CB. (1989). Stable isotopes. In Plant physiological ecology: Field methods and instrumentation. (Piercy RW, Ehleringer J, Mooney HA, Rundel PW, Eds.) (pp. 281–300). Chapman & Hall.

- 11.Farquhar GD, O’Leary MH, & Berry JA. (1982). On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 9, 119–129.

- 12.Garnier E, Salager J-L, Laurent G, & Sonié L. (1999). Relationship between photosynthesis, nitrogen and leaf structure in 14 grass species and their dependence on the basis of expression. New Phytologist, 143, 35–47.

- 13.Gilman IS, & Edwards EJ. (2020). Crassulacean acid metabolism. Current Biology, 30, R57–R62.

- 14.Gleason SM, Blackman CJ, Cook AM, Laws CA, & Westoby M. (2014). Whole-plant capacitance, embolism resistance and slow transpiration rates all contribute to longer desiccation times in woody angiosperms from arid and wet habitats. Tree Physiology, 34, 275–284.

- 15.Guo B, Arndt SK, Miller RE, Szota C, & Farrell C. (2024). Does succulence in woody plants delay desiccation, and is stored water used to maintain physiological function during drought conditions? Physiologia Plantarum, 176, e14616.

- 16.Groom PK, & Lamont BB. (1999). Which common indices of sclerophylly best reflect differences in leaf structure? Ecoscience, 6, 471–474.

- 17.Groom PK, Lamont BB, Leighton S, Leighton P, & Burrows C. (2004). Heat damage in sclerophylls is influenced by their leaf properties and plant environment. Ecoscience, 11, 94–101.

- 18.Grubb PJ, Marañón T, Pugnaire FI, & Sack L. (2015). Relationships between specific leaf area and leaf composition in succulent and non-succulent species of contrasting semi-desert communities in south-eastern Spain. Journal of Arid Environments, 118, 69–83.

- 19.Hanba YT, Miyazawa SI, & Terashima I. (1999). The influence of leaf thickness on the CO2 transfer conductance and leaf stable carbon isotope ratio for some evergreen tree species in Japanese warm-temperate forests. Functional Ecology, 13, 632–639.

- 20.Herrera A. (2020). Are thick leaves, large mesophyll cells and small intercellular air spaces requisites for CAM? Annals of Botany, 125, 859–868.

- 21.Hulley IM, Viljoen AM, Tilney PM, Van Vuuren SF, Kamatou GPP, & Van Wyk BE. (2010). The ethnobotany, leaf anatomy, essential oil variation and biological activity of Pteronia incana (Asteraceae). South African Journal of Botany, 76(4), 668–675.

- 22.Lamont BB & Lamont HC. (2000). Utilizable water in leaves of eight arid species as derived from pressure-volume curves and chlorophyll fluorescence. Physiologia Plantarum, 110, 64–71.

- 23.Lamont BB, & Lamont HC. (2025). Contrasting water, dry matter and air contents distinguish orthophylls, sclerophylls and succophylls (leaf succulents). Oecologia, 207, 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-025-05686-4

- 24.Lamont BB, Groom PK, & Cowling RM. (2002). High leaf mass per area of related species assemblages may reflect low rainfall and carbon isotope discrimination rather than low phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations. Functional Ecology, 16, 403–412.

- 25.Lamont BB, Groom PK, Williams M, & He T. (2015). LMA, density and thickness: Recognizing different leaf shapes and correcting for their non-laminarity. New Phytologist, 207, 942–947.

- 26.Landrum JV. (2002). Four succulent families and 40 million years of evolution and adaptation to xeric environments: What can stem and leaf anatomical characters tell us about their phylogeny? Taxon 51, 463–473.

- 27.Lauterbach M, van der Merwe PDW, Keßler L, Pirie MD, Bellstedt DU, & Kadereit G. (2016). Evolution of leaf anatomy in arid environments–a case study in southern African Tetraena and Roepera (Zygophyllaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 97, 129–144.

- 28.Linton MJ, & Nobel PS. (2001). Hydraulic conductivity, xylem cavitation, and water potential for succulent leaves of Agave deserti and Agave tequilana. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 162(4), 747–754.

- 29.Males J. (2017). Secrets of succulence. Journal of Experimental Botany, 68(9), 2121–2134.

- 30.Maxwell, K, von Caemmerer, S, & Evans, JR. (1997). Is a low internal conductance to CO2 diffusion a consequence of succulence in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism? Functional Plant Biology, 24(6), 777–786.

- 31.Melo-de-Pinna GF, Ogura AS, Arruda EC, & Klak C. (2014). Repeated evolution of endoscopic peripheral vascular bundles in succulent leaves of Aizoaceae (Caryophyllales). Taxon, 63(5), 1037–1052.

- 32.Miller G. (1985). Plant-Water Relations along a Rainfall Gradient, between the Succulent Karoo and Mesic Mountain Fynbos, in the Cedarberg Mountains near Clanwilliam, South Africa. Master’s Thesis. University of Cape Town.

- 33.Milton SJ, Yeaton RI, Dean WRJ, & Vlok JHJ. (1997). Succulent karoo. In Vegetation of southern Africa. (Cowling RM, Richardson DM, Pierce SM, Eds.) (pp. 131–166). Cambridge University Press.

- 34.Niinemets Ü. (1999). Components of leaf dry mass per area — thickness and density — alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytologist, 144, 35–47.

- 35.Özdemir C, Baran P, & Aktas K. (2009). Anatomical studies in Salvia viridis L. (Lamiaceae). Bangladesh Journal of Plant Taxonomy, 16(1), 65–71.

- 36.Pérez-López AV, Lim SD, & Cushman JC. (2023). Tissue succulence in plants: Carrying water for climate change. Journal of Plant Physiology, 289, 154081.

- 37.Pyankov VI, Kondrachuk AV, & Shipley B. (1999). Leaf structure and specific leaf mass: The alpine desert plants of the Eastern Pasmirs, Tadjikistan. New Phytologist, 143, 131–142.

- 38.Radford S, & Lamont BB. (1992). An instruction manual for ‘Template’–A rapid, accurate program for calculating and plotting water relations data obtained from pressure-volume curves. Environmental Biology, Curtin University. (no longer available)

- 39.Richards MB, & Lamont BB. (1996). Post-fire mortality and water relations of three congeneric shrub species under extreme water stress—a trade-off with fecundity? Oecologia, 107, 53–60.

- 40.Ripley BS, Abraham T, Klak C, & Cramer MD. (2013). How succulent leaves of Aizoaceae avoid mesophyll conductance limitations of photosynthesis and survive drought. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64(18), 5485–5496.

- 41.*Roderick ML, Berry SL, & Noble IR. (1999a). The relationship between leaf composition and morphology at elevated CO2 concentrations. New Phytologist, 143, 63–72.

- 42.Roderick ML, Berry SL, & Noble IR. (1999c). On the relationship between leaf composition, morphology and function of leaves. Functional Ecology, 13, 696–710.

- 43.Roderick ML, Berry SL, Noble IR, & Farquhar GD. (1999b). A theoretical approach to linking the composition and morphology with the function of leaves. Functional Ecology, 13, 683–695.

- 44.Schulze E-D, Williams RJ, & Farquhar GD. (1998). Carbon and nitrogen discrimination and nitrogen nutrition of trees along a rainfall gradient in northern Australia. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 25, 413–425.

- 45.Swanborough PW, Lamont BB, & February EC. (2003). δ13C and water-use efficiency in Australian grasstrees and South African conifers over the last century. Oecologia, 136, 205–212.

- 46.Teeri JA, Tonsor SJ, & Turner M. (1981). Leaf thickness and carbon isotope composition in the Crassulaceae. Oecologia, 50(3), 367–369.

- 47.Vendramini F, Diaz S, Gurvich DE, Wilson PJ, Thompson K, & Hodgson JG. (2002). Leaf traits as indicators of resource-use strategy in floras with succulent species. New Phytologist, 154, 147–157.

- 48.von Willert DJ, & Brinckman E. (1986). Sukkulenten und ihr Überleben in Wüsten. Naturwissenschaften, 73, 57–69.

- 49.von Willert DJ, Eller BM, Werger M, Brinckman E, & Ihlenfeldt H-D. (1992). Life strategies of succulents in deserts: With special reference to the namib desert. Cambridge University Press.

- 50.Wang Z, Huang H, Wang H, Peñuelas J, Sardans J, Niinemets Ü, & Wright IJ. (2022). Leaf water content contributes to global leaf trait relationships. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1–9.

- 51.Wilson PJ, Thompson K, & Hodgson JG. (1999). Specific leaf area and leaf dry matter content as alternative predictors of plant strategies. New Phytologist, 143, 155–162.

- 52.Winter K, Aranda J, & Holtum JA. (2005). Carbon isotope composition and water-use efficiency in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism. Functional Plant Biology, 32(5), 381–388.

- 53.Winter K, & Holtum JAM. (2002). How closely do the δ13C values of Crassulacean acid metabolism plants reflect the proportion of CO2 fixed during day and night? Plant Physiology, 129, 1843–1851.

- 54.Winter K, Troughton JH, Evenari M, Läuchli A, & Lüttge U. (1976). Mineral ion composition and occurrence of CAM-like diurnal malate fluctuations in plants of coastal and desert habitats of Israel and the Sinai. Oecologia, 25, 125–143.

- 55.Witkowski ETF, & Lamont BB. (1991). Leaf specific mass confounds leaf density and thickness. Oecologia, 88, 6–493.

- 56.Williams MR, Lamont BB, & He T. (2022). Forum: Dealing with “the spectre of ‘spurious’ correlations”: Hazards in comparing ratios and other derived variables with a randomization test to determine if a biological interpretation is justified. Oikos, 2022, e08575.

- 57.*Wright IJ, Groom PK, Lamont BB, Poot P, Prior LD, Reich PB, Schulze E-D, Veneklaas VJ, & Westoby M. (2004). Leaf trait relationships in Australian plant species. Functional Plant Biology, 31, 551–558.

- 58.Wright IJ, & Westoby M. (2002). Leaves at low versus high rainfall: Coordination of structure, lifespan and physiology. New Phytologist, 155, 403–426.

How to Cite

Lamont, B. B., Eccles, N. S., & Lamont, H. C. (2025). Leaf Thickness as Key to the Contrasting Water and Nutrient Relations of Eight Arid-Climate Species, Including Water-Loss Resistance. Plant Ecophysiology, 1(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.53941/plantecophys.2025.100011

RIS

BibTex

Copyright & License

Copyright (c) 2025 by the authors.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Contents

References