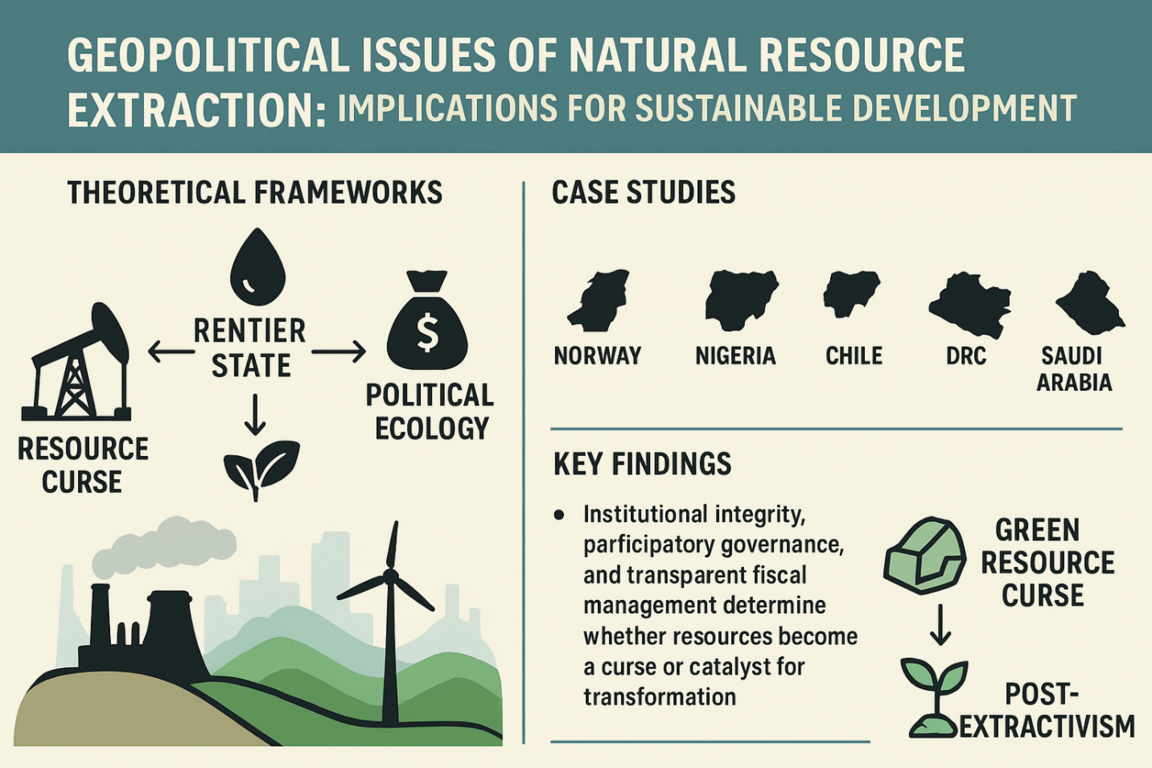

- Focused and comparative analysis on natural resource extraction.

- Convergence or divergence of resource curse, rentier state, and political ecology.

- Evaluation of whether resources become a curse or catalyst for transformation.

- Bridging classic resource theories with contemporary green-transition politics and post-extractive development debates.

- Open Access

- Article

Geopolitical Issues of Natural Resource Extraction: Implications for Sustainable Development

- Avik Sinha

Author Information

Received: 12 Oct 2025 | Revised: 27 Nov 2025 | Accepted: 10 Dec 2025 | Published: 17 Dec 2025

Highlights

Abstract

Natural resource extraction remains one of the most politically consequential and environmentally contentious activities of the twenty-first century. It promises fiscal revenues, foreign exchange, employment, and industrial linkages, yet simultaneously fuels conflict, corruption, ecological degradation, and geopolitical rivalry. This paper narrows its scope to provide a more focused and comparative analysis of how governance quality, institutional design, and global power structures shape the political economy of extraction. Rather than treating cases broadly, it emphasizes three interlinked theoretical frameworks—the resource curse, the rentier state, and political ecology—and evaluates how they converge and diverge in explaining developmental outcomes. The study also develops the emerging ideas of the “green resource curse,” highlighting new dependencies created by renewable energy minerals, and “post-extractivism,” describing governance models that prioritize ecological sustainability and social equity. Country cases including Norway, Nigeria, Chile, the DRC, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia are thematically analyzed through governance, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions, with figures explicitly linked to the discussion. The findings underscore that institutional integrity, participatory governance, and transparent fiscal management determine whether resources become a curse or catalyst for transformation. The paper concludes by outlining its limitations and highlighting its original contribution: bridging classic resource theories with contemporary green-transition politics and post-extractive development debates.

Graphical Abstract

References

- 1.

Auty, R.M. Industrial policy reform in six large newly industrializing countries: The resource curse thesis. World Dev. 1994, 22, 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90165-1

- 2.

Ross, M.L. The Oil curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012.

- 3.

Beblawi, H.; Luciani, G. The Rentier State; Routledge: London, UK, 2015.

- 4.

Sachs, J.D.;Warner, A. Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995.

- 5.

Karl, T.L. The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-states; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 26.

- 6.

Mehlum, H.; Moene, K.; Torvik, R. Institutions and the resource curse. Econ. J. 2006, 116, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01045.x

- 7.

International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023.

- 8.

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. EITI Progress Report 2024; Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI International Secretariat): Oslo, Norway, 2024.

- 9.

Bridge, G; Le Billon, P. Oil; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017.

- 10.

Haber, S.; Menaldo, V. Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2011, 105, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000584

- 11.

International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024.

- 12.

Bryant, R.L.; Bailey, S. Third World Political Ecology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1997.

- 13.

Robbins, P. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019.

- 14.

Ferguson, J. Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2006.

- 15.

Le Billon, P. Resources, wars and violence. In The International Handbook of Political Ecology; Bryant, R.L., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 176–188.

- 16.

Watts, M.J. Silent Violence: Food, Famine, and Peasantry in Northern Nigeria; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2013; Volume 15.

- 17.

Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1369–1401. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

- 18.

Campbell, B. Factoring in governance is not enough. Mining codes in Africa, policy reform and corporate responsibility. Miner. Energy-Raw Mater. Rep. 2003, 18, 2–13.

- 19.

Bridge, G. Global production networks and the extractive sector: Governing resource-based development. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 389–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn009

- 20.

Haufler, V. Disclosure as governance: The extractive industries transparency initiative and resource management in the developing world. Glob. Environ. Politics 2010, 10, 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP a 00014

- 21.

Ostensson, O.; Lof, A. Downstream Activities: The Possibilities and the Realities; WIDER Working Paper; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2017/337-0

- 22.

World Bank. World Development Indicators 2024; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator

- 23.

Sovacool, B.K.; Ali, S.H.; Bazilian, M.; et al. Sustainable minerals and metals for a low-carbon future. Science 2020, 367, 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz6003

- 24.

Natural Resource Governance Institute. Resource Governance Index 2023; NRGI: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- 25.

Collier, P.; Venables, A.J. Closing coal: Economic and moral incentives. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2014, 30, 492–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/gru024

- 26.

van der Ploeg, F. Natural resources: Curse or blessing? J. Econ. Lit. 2011, 49, 366–420. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.2.366

- 27.

Central Bank of Nigeria. Statistical Bulletin 2023; CBN: Abuja, Nigeria, 2024.

- 28.

Obi, C. The Geopolitical Consequences of Oil in Africa: The Case of Nigeria. Brown J. World Aff. 2020, 26, 1–18.

- 29.

Mjøset, L.; Cappelen, A˚ . The integration of the Norwegian oil economy into the world economy. In The Nordic Varieties of Capitalism; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 167–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0195-6310(2011)0000028008

- 30.

Norges Bank Investment Management. Historic Investments. All Investments 2024; NBIM: Oslo, Norway, 2025. Available online: https://www.nbim.no/en/investments/all-investments/#/ (accessed on 10 October 2025)

- 31.

Mommer, B. Fiscal Regimes and Oil Revenues in the UK, Alaska and Venezuela; Oxford Institute for Energy Studies: Oxford, UK, 2001.

- 32.

Corrales, J.; Penfold-Becerra, M. Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chavez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- 33.

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. 2024 OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin; OPEC Secretariat: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- 34.

Corrales, C. The Political Economy of the New Extractivism and Revolutionary Strategies in Ecuador and Venezuela; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2021.

- 35.

Ellner, S. Class strategies in chavista Venezuela: Pragmatic and populist policies in a broader context. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2019, 46, 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X18798796

- 36.

Autesserre, S. Dangerous tales: Dominant narratives on the Congo and their unintended consequences. Afr. Aff. 2012, 111, 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adr080

- 37.

Global Witness. Regions 2025; Global Witness: London, UK, 2025. Available online: https://globalwitness.org/en/regions/ (accessed on 10 October 2025)

- 38.

Seay, L. What’s Wrong with Dodd-Frank 1502? Conflict Minerals, Civilian Livelihoods, and the Unintended Consequences of Western Advocacy; Center for Global Development (CGD): Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- 39.

Sovacool, B.K. The precarious political economy of cobalt: Balancing prosperity, poverty, and brutality in artisanal and industrial mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 915–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2019.05.018

- 40.

Chilean Copper Commission. Yearbook of Statistics on Copper and Other Minerals; Chilean Copper Commission: Santiago, Chile, 2024. Available online: https://www.cochilco.cl/web/anuariode-estadisticas-del-cobre-y-otros-minerales/ (accessed on 10 October 2025)

- 41.

Sovacool, B.K.; Baum, C.M.; Low, S. Risk–risk governance in a lowcarbon future: Exploring institutional, technological, and behavioral tradeoffs in climate geoengineering pathways. Risk Anal. 2023, 43, 838–859. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13932

- 42.

Fattouh, B.; Kilian, L.; Mahadeva, L. The role of speculation in oil markets: What have we learned so far? Energy J. 2013, 34, 7–33. https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.34.3.2

- 43.

Colgan, J.D. The emperor has no clothes: The limits of OPEC in the global oil market. Int. Organ. 2014, 68, 599–632. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000489

- 44.

Colgan, J.D. Oil, domestic politics, and international conflict. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.005

- 45.

Luciani, G. Global oil markets: The need for reforms. In Handbook of Oil Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 90–106.

- 46.

Mitchell, J.V.; Mitchell, B. Structural crisis in the oil and gas industry. Energy Policy 2014, 64, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.094

- 47.

Brautigam, D. The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009.

- 48.

Gallagher, K.S.; Qi, Q. Chinese overseas investment policy: Implications for climate change. Glob. Policy 2021, 12, 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12952

- 49.

Patey, L.A. How China loses: The Pushback against Chinese Global Ambitions; Oxford University Press: NewYork, NY, USA, 2021.

- 50.

Brautigam, D. Chinese loans and African structural transformation. In China-Africa and an Economic Transformation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 129–146.

- 51.

International Energy Agency. Critical Minerals Market Review, 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1787/9cdf8f39-en

- 52.

Kolstad, I.; Søreide, T. Corruption in natural resource management: Implications for policy makers. Resour. Policy 2009, 34, 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2009.05.001

- 53.

International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Policy Pivot, Rising Threats; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- 54.

Adam, A. Ghana Petroleum Revenue Management Act: Back to Basics; Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI): New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- 55.

United Nations Environment Programme. Global Resources Outlook 2024; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2024.

- 56.

Bebbington, A. Extractive industries, socio-environmental conflicts and political economic transformations in Andean America. In Socioenvironmental Conflicts, Economic Development and Extractive Industries; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–26.

- 57.

Escobar, A.; Chaparro, M. Divergencias, alternativas y transiciones de los modelos y las comunicaciones para el buen vivir. Chasqui 2020, 144, 19–36.

- 58.

Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Gov Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025. https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/programs/participation-indigenouspeoples/implementing-united-nations-declaration-rights-indigenouspeoples.html

- 59.

Farthing, L.C.; Kohl, B.H. Evo’s Bolivia: Continuity and Change; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2014.

- 60.

Gudynas, E. Extractivisms: Tendencies and consequences. In Reframing Latin American Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 61–76.

- 61.

Sovacool, B.K.; Newell, P.; Carley, S.; et al. Equity, technological innovation and sustainable behaviour in a low-carbon future. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01257-8

- 62.

Human Rights Watch. World Report 2024; Seven Stories Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024.

- 63.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1787/15f5f4b3-en

- 64.

International Energy Agency. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/policies/16156-inflation-reduction-act-of-2022 (accessed on 10 October 2025)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.