Qifuyin (QFY) has been used for the treatment of senile dementia in traditional Chinese medicine. Polysaccharides are the main components in QFY, but they have not been sufficiently studied. Here, we extracted QFY polysaccharides (QFYP) with 29.9 ± 0.81% yield and 70.1 ± 0.10% purity using hydrothermal extraction and alcohol precipitation. The QFYP-1 and QFYP-2 were separated through DEAE-52 cellulose column chromatography. The 207.1 mg QFYP-1 was obtained with 20.71% yield and 92.8% purity. The 108.0 mg QFYP-2 was extracted with 10.80% yield and 84.5% purity. The in vitro anti-oxidant assay showed that QFYP could scavenge DPPH, ABTS+, O2- radicals and chelate Fe2+, with IC50 of 0.43 mg/mL, 0.92 mg/mL, 3.4 mg/mL and 6.5 mg/mL respectively. In vivo animal experiments showed that QFYP increased the head regeneration score of the decapitated planaria after 72 h. The free-swimming behavior test of the post-regenerated planaria showed that QFYP increased the total motion distance and movement angle of planaria. This indicated that QFYP was successfully prepared, and exerted anti-oxidant effects and promoted regenerative activities.

- Open Access

- Article

Preparation of Polysaccharides from Qifuyin and Investigation of Their Anti-Oxidant and Regenerative Effects Based on Planaria

- Qingxian Wang †,

- Yuexiao Zou †,

- Shixue Wang,

- Xiaorui Cheng *

Author Information

Received: 25 Dec 2024 | Revised: 13 Jan 2025 | Accepted: 21 Jan 2025 | Published: 18 Aug 2025

Abstract

Keywords

traditional Chinese medicine | Qifuyin polysaccharides | anti-oxidant | regeneration | planaria

1.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disease. Its main clinical manifestations include progressive memory decline and cognitive dysfunction. One of the main pathologic features of AD are the loss of neurons, reduced nerve cell function, and synaptic structural damage. In aged individuals, nerve cells show reduced capacity to renew themselves and repair. In recent years, the prevalence and mortality of AD have gradually increased, and it has become the third most lethal disease in the world after tumor and cardiovascular diseases [1]. By 2060, the number of AD patients aged 65 years and older is expected to increase to 13.8 million, imparting a huge cost to society and families [2]. Despite the significant research and development of AD treatment drugs, no effective treatments have been developed.

The Qifuyin (QFY) derived from “jing yue Quan shu”. QFY was composed of Ginseng, Polygala tenuifolia, Spina Date Seed, Rehmannia glutinosa, Angelicae Sinensis, Atractylodes macrocephala, Glycyrrhiza [3]. It has been used to treat senile dementia in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) [3-5]. Modern clinical studies show that the treatment of QFY effectively increases the daily living ability score, MMSE score and cognitive function score of AD patients [6,7]. Experimental pharmacological research shows that QFY can attenuate AGEs-induced AD-like pathophysiological changes [5] and ameliorate synaptic injury and oxidative stress in APP/PS1 mice [8]. Our previous experiments revealed that the administration of QFY improved the learning and memory ability of APP/PS1 and 5×FAD mice [9,10]. However, the pharmacodynamic mechanism of QFY in treating AD is not well understood.

Polysaccharides are the most abundant and effective components of QFY. The functions of polysaccharides from herbs containing QFY have been widely reported. Ginseng polysaccharides showed several bioactivities, such as anti-inflammatory [11], anti-tumor [12–14], anti-cancer [13,15,16] and modulating intestinal microbiota [11,12]. Other herbs polysaccharides such as Angelica sinensis polysaccharide [17], Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides [18], Atractylodes macrocephala polysaccharides [19] had anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor bioactivities. Polysaccharides are complex components of the TCM. The activity of polysaccharide is influenced by monosaccharide composition, branched chain structure and molecular weight, among other factors. Ginseng polysaccharide PGP2a, with molecular weight of 3.2 × 104 Da and monosaccharide composition of galactose, arabinose, glucose and galacturonic acid in the molar ratio of 3.7∶1.6∶0.5∶5.4, possess anti-gastric cancer biological activity [13]. Ginseng polysaccharide PGPW1, with a molecular weight of 3.5 × 105 Da and monosaccharide composition of glucose, galactose, mannose and arabinose in the molar ratio of 3.3:1.2:0.5:1, was found strong anti-bladder cancer biological activity [16]. Angelica sinensis polysaccharide (ASP) is composed of glucose, galactose, arabinose, rhamnose, fucose, xylose and galacturonic acid, with a molecular weight ranging between 3.2 × 103 and 2.6 × 106 Da [17]. Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides is mainly composed of Ara, glucose, galactose, and a small amount of rhamnose, mannose, xylose, and galacturonic acid [18]. However, the QFY polysaccharides have not been studied.

Planarians are fresh-water flatworms that are generally less than 1 cm long. It possesses a central nervous system consisting of a bilobed “brain” called the cephalic ganglia and two ventral nerve cords that traverse the length of the body and support a peripheral nerve ladder [20]. Planarias has a strong ability to regenerate. They can regenerate new heads, tails, sides, or entire organisms from small body fragments in a process taking days to weeks [21]. In addition, the small size and easy breeding of planaria make it a good animal model for investigating regeneration. Planaria has been extensively used a model to study regeneration activity [21‒24], neoblasts [21,25‒27], neurotoxicology [28‒32] and screen for regenerative drugs [33‒37].

The aims of the present study were to prepare and evaluate the biological activity of QFY polysaccharides. QFY polysaccharides were obtained by water extraction and alcohol precipitation. The polysaccharides were separated by DEAE-52 cellulose column chromatography. The anti-oxidant activity of polysaccharides was evaluated through DPPH, ABTS+, and O2- radical assays. The decapitated planaria regeneration model to evaluate the promoting regeneration effects of QFY polysaccharides.

2.Materials and Methods

2.1.Materials

Ginseng (2012012), Polygala tenuifolia (2012001), Spina Date Seed (2007002) were purchased from An Guo Shi Ju Yao Tang Pharmaceutical Co. (Hebei, China). Rehmannia glutinosa (201205), Angelicae Sinensis (201203), Atractylodes macrocephala (210101), Glycyrrhiza (201201) (Prepared) were purchased from An Guo Shi An Xing Chinese Medicine Decoction pieces Co. (Hebei, China). All herbs were identified by Prof. Yongqing Zhang, an experienced botanist in Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Analytical pure ethanol, n-butyl alcohol were purchased from Fu Yu Fine Chemical Co. (Tianjin, China). Analytical pure chloroform was purchased from Kunshan Jin Cheng Reagent Co. (Jiangsu, China). Concentrated sulfuric acid was purchased from Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China). Phenol was purchased from Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co. (Shanghai, China). Standard glucose and standard bovine serum albumin were purchased from Jinan Xing Ji Medical Equipment Co. (Shandong, China). Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 was purchased from Jinan Chang Ge Biotechnology Co. (Shandong, China). DPPH, potassium persulfate, ABTS+, phenazine monosodium salt, NBT, and EDTA were purchased from Anxia Biotechnology Co. (Shandong, China). Vitamin C and PMS were purchased from Zhongchu Hengtong Biotechnology Co. (Shandong, China). All other chemicals were purchased from local suppliers in Jinan and used without further purification.

2.2.Degrease and Decolorize of QFY Slices

QFY was total 43 g, including Ginseng (6 g), Rehmannia glutinosa (9 g), Angelicae (9 g), Atractylodes macrocephala (5 g), Glycyrrhiza (Prepared) (3 g), Spina Date Seed (6 g), Polygala tenuifolia (5 g). QFY was put into a 1000 mL round-bottom flask, 320 mL 95% ethanol was added. After 6 h of heating reflux, the mixture was filtered. the filter residue was dried in the oven at 60 °C, which was the degreased and decolorized QFY slices.

2.3.Preparation of QFY Polysaccharides

The QFY slices were degreased and decolorized, then placed into a 1000 mL round-bottom flask, and 430 mL distilled water was added and stirred evenly with magnetic force (Qifuyin: water = 1∶10). Soaked at 25 °C for 30 min. After 2 h of heating reflux, the mixture was filtered. The above process was repeated 3 times. The filtrates were combined and concentrated to 20 mL. After the concentrate was naturally cooled, 80 mL alcohol was added for alcohol precipitation. Precipitation could be seen. After standing at 4 °C for 48 h, the mixed solution was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the precipitation was lyophilized to obtain QFY polysaccharides (QFYP).

The sample was weighted using an analytical balance, and the extraction yield (y) was calculated using Equation (1):

where w1 represents the lyophilized mycelia weight, and w represents the QFY weight.

Purity of the polysaccharide was calculated using Equation (2):

where w2 represents the total sugar of the crude polysaccharide, determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid assay. w1 represents the lyophilized mycelia weight.

2.4.Sevage Deproteinization of QFY Polysaccharides

The lyophilized polysaccharide sample was dissolved in water (5%), then heated (70 °C) to complete dissolution. The radio of Sevage reagent (chloroform:n-butanol = 4∶1) to polysaccharides aqueous solution was 1∶5. Deproteinization was repeated 5 times. After complete oscillation by vortex, the samples were placed overnight at 25 °C and centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min. Next, the supernatant was collected and lyophilized.

2.5.Column Chromatography Isolation of QFY Polysaccharides

The deproteinized polysaccharide sample was dissolved in water (25 mg/mL), and heated (70 °C) to complete dissolution. Through the separation by DEAE Cellouse-52 column (Φ25 mm × 200 mm), the polysaccharide solution was eluted with distilled water and 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4 mol/L NaCl solution at a flow rate of 5.0 mL/min. A tube of isovolumetric elution solution was collected every 3 min and the polysaccharide content was determined using phenol-sulfuric acid assay. The elution curve was plotted with the number of tubes of eluent as abscissa and the absorbance at 490 nm as ordinate. The only eluting peak was collected and lyophilized.

2.6.Anti-Oxidant Activities of QFY Polysaccharides In Vitro

(1).DPPH radical-scavenging activity

DPPH radical-scavenging activity was measured as previously described [38]. 1.0 mL polysaccharide samples at different concentrations (0–2.0 mg/mL) were mixed with 1.0 mL DPPH solutions (0.1 mmol/L dissolved in ethanol). The mixture was shaken vigorously and then incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in the dark. The absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. Vitamin C served as a positive control group. The scavenging activity was calculated using the following Equation (3):

where A1 was the absorbance for samples mixed with DPPH, A2 was the absorbance for water mixed with DPPH solution, and A0 was the absorbance for samples mixed with water. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

(2).ABTS+ radical-scavenging activity

The ABTS+ radical scavenging activity was measured using a previously described method [39]. Briefly, 7.0 mM ABTS solution was prepared using 2.45 mM K2S2O8 solution, the mixture was stirred for 12 h in the dark at 25 °C. The ABTS+ mixture was diluted with PBS (pH 7.4), and the absorption value measured at 734 nm was 0.700 ± 0.020. 0.5 mL polysaccharide samples at different concentrations (0–10.0 mg/mL) were mixed with 2.0 mL ABTS-working solution, the mixture was shaken vigorously and then incubated at 30 °C for 2 h in the dark. The absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 734 nm. Vitamin C served as a positive control group. The IC50 was calculated using the following Equation (4):

where A1 was the absorbance for samples mixed with ABTS-working solution, A2 was the absorbance for sample mixed with water, and A0 was the absorbance for blank control absorbance. The IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

(3).O2- radical-scavenging activity

The scavenging activity of polysaccharides on the superoxide radical was assayed using methods reported by Robak and Gryglewski [40]. Briefly, 50 μL of different concentrations of polysaccharide sample (0.25–5.0 mg/mL) was mixed with 50 μL NBT solution (0.30 mmol/L), 50 μL NADH solution (0.936 mmol/L), 50 μL PMS solution (0.12 μmol/L). The reaction mixture was shaken thoroughly and then incubated at 25 °C for 5 min, and the absorbance at 569 nm was measured. The scavenging ability of polysaccharide on the superoxide radical was calculated according to the following Equation (5).

where A1 was the absorbance of the polysaccharide samples group, and A2 was the absorbance for samples solution without NBT solution, and A0 was the absorbance for blank control absorbance, respectively. The IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

(4).Fe2+-chelating activity

The Fe2+-chelating rate was determined using a previously reported method with slight modification [39]. 100 μL of polysaccharide samples at a series of concentrations (0–40 mg/mL) were mixed with 20 μL of FeCl2 (2 mmol/L), 50 μL of ferrozine solution (5 mmol/L), and 135 μL of distilled water. The reaction was shaken vigorously and left to stand at 25 °C for 10 min. The absorbance of the mixture was determined at 562 nm. The Fe2+-chelating rate was calculated using the following Equation (6).

where A1 was the absorbance of the polysaccharide samples group, A2 was the absorbance for samples solution mixed water, and A0 was the absorbance for FeCl2 solution mixed with water, respectively. The IC50 was calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

2.7.Test Animals

Planaria, strain ZB-1, were provided by Dr. Xu Zhenbiao of Shandong University of Technology (Zibo, Shandong, China). They were maintained at 22 °C in dechlorinated tap water, from which chlorine naturally dissipated by letting the water sit in open stainless-steel containers for 3 d. The animals were fed fresh beef liver twice a week but were not fed for 7 d before the regeneration assay.

2.8.Tolerance Concentration of QFY Polysaccharides in Planaria

Planarians were exposed to QFY polysaccharides concentrations of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 mg/mL. The experiment was examined at 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 16 h, 32, 64 h for mortality and number of dead organisms recorded. Animals with body degeneration or no detectable movement under intense light were considered dead. The death rate of planaria with concentration at different times was recorded. The maximum concentration that was not lethal to planaria was defined as the maximum tolerance concentration of planaria.

2.9.Regeneration Assay

A regeneration assay was performed for the control group and three treatment groups. Based on the results of the tolerance concentration of QFY polysaccharides, the polysaccharides were tested in the regeneration assays at concentrations of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/mL. The planaria were decapitated immediately behind the auricles, as described previously [29], and used immediately. Eight decapitated planaria were kept in 10 mL of test media in 6-hole plates and three replicates for each concentration with four groups. The regeneration assays were conducted under static conditions at 22 °C with a 12∶12 h dark:light cycle. The decapitated animals were observed under a dissection microscope at 72, 88, 96, 104, 112, and 116 h after decapitation. The regeneration score standard of planaria was determined using a previous method with slight modifications [31].

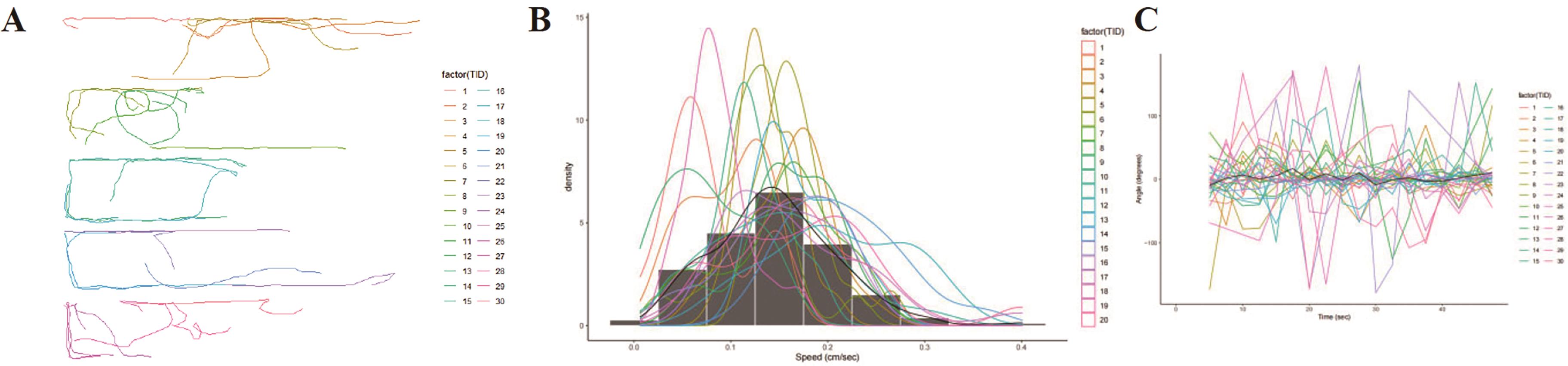

2.10.Free Swimming Behavior Test of the Post-Regenerated Planaria

The behavior of the post-regenerating planaria were tested by a self-made multifunctional detection tank after six days of administration with polysaccharide. The speed, angle of motion, total distance of motion were calculated using Image J and R (4.2.1) [41].

2.11.Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used to plot and analyze data. Data between the two groups were compared using Student’s t-test. Comparison of data from multiple groups against one group was conducted using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

3.Result

3.1.Preparation of QFY Polysaccharide

In this work, the content of polysaccharides was determined using the phenol-concentrated sulfuric acid colorimetry, and glucose was used as the standard. The extraction yield of polysaccharide was 29.9 ± 0.81% with 70.1 ± 0.10% purity. Six polysaccharides fractions of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 were separated by DEAE-52 cellulose column chromatography (Figure 1). The QFYP-1 was obtained 207.1 mg with 20.71% yield and 92.8% purity. The QFYP-2 was obtained 108.0 mg with 10.80% yield and 84.5% purity. Fraction 1 and 2 polysaccharides were all white flocculent solids after lyophilized.

3.2.Anti-Oxidant Activities of QFY Polysaccharides In Vitro

The DPPH radical, ABTS+ radical and O2- radical scavenging activities of QFY polysaccharides were increased with the increasing concentrations (Figure 2A,C,E). The IC50 of polysaccharides were 0.43 mg/mL, 0.92 mg/mL and 3.4 mg/mL for DPPH radical, ABTS+ radical and O2- radical, respectively. The IC50 of positive control vitamin C was 4.8 × 10-3 mg/mL, 1.4 × 10-2 mg/mL and 8.1 × 10-2 mg/mL (Figure 2B,D,F). Similarly, the Fe2+-chelating rate increased with the increase in the concentrations of QFY polysaccharides (Figure 2G). The IC50 of polysaccharides was 6.5 mg/mL, while the IC50 of positive control EDTA was 3.8 × 10-2 mg/mL (Figure 2H).

3.4.The Effect of QFY Polysaccharides on the Head Regeneration of Planaria

The results of QFY polysaccharides tolerance concentration of planaria are shown in Figure 3. With the increase of QFY polysaccharides concentration, the death rate of planaria increased. Moreover, the death rate of planaria increased with the extension of time under the same concentration. The mortality of planaria was concentration-dependent. At concentrations 8 and 10 mg/mL, the planaria appeared dead after 1 h, until all died quickly. At concentrations 4 and 6 mg/mL, the planaria died with time, until all died at 8 h and 64 h, respectively. At a concentration of 2 mg/mL or less, the planaria did not die during the entire experiment. Even after extending the observation period to 128 h, the planaria exhibited no signs of mortality. In this work, we set the maximum tolerance concentration of planaria as 2.0 mg/mL, and conducted the subsequent regeneration experiment of planaria.

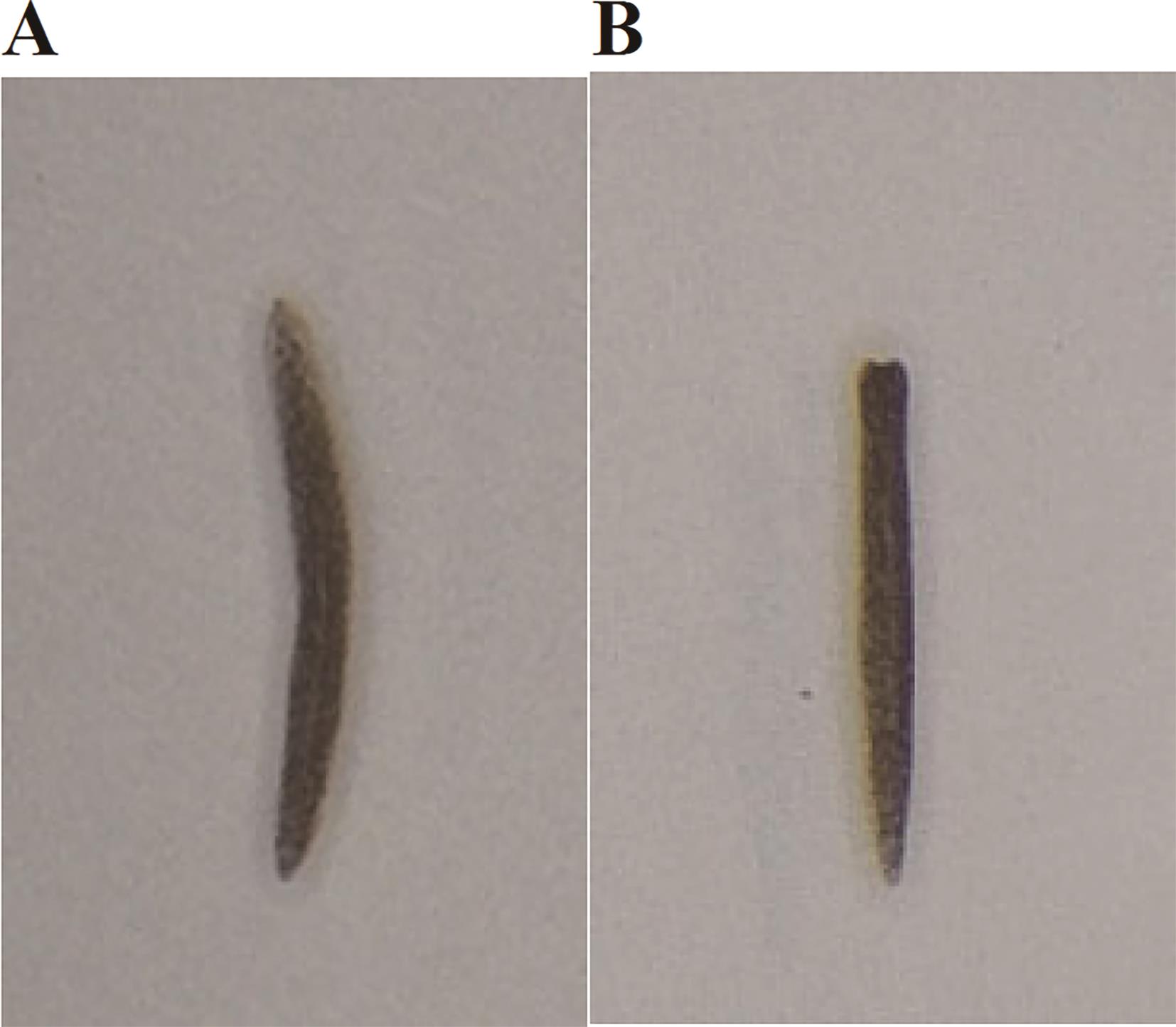

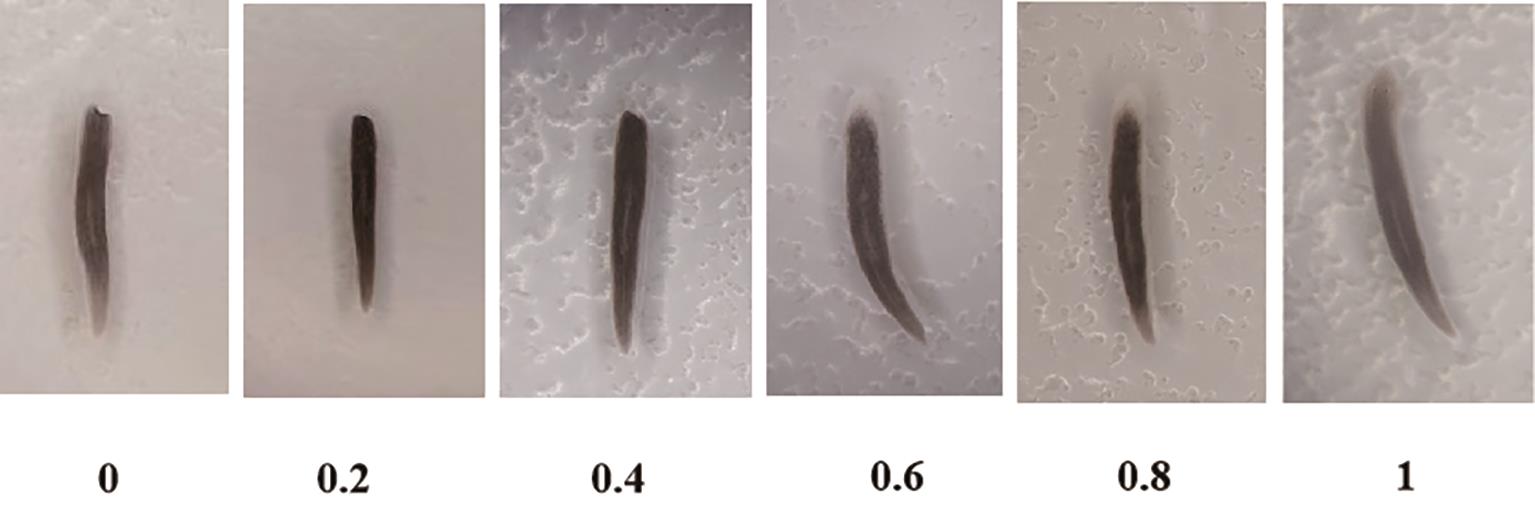

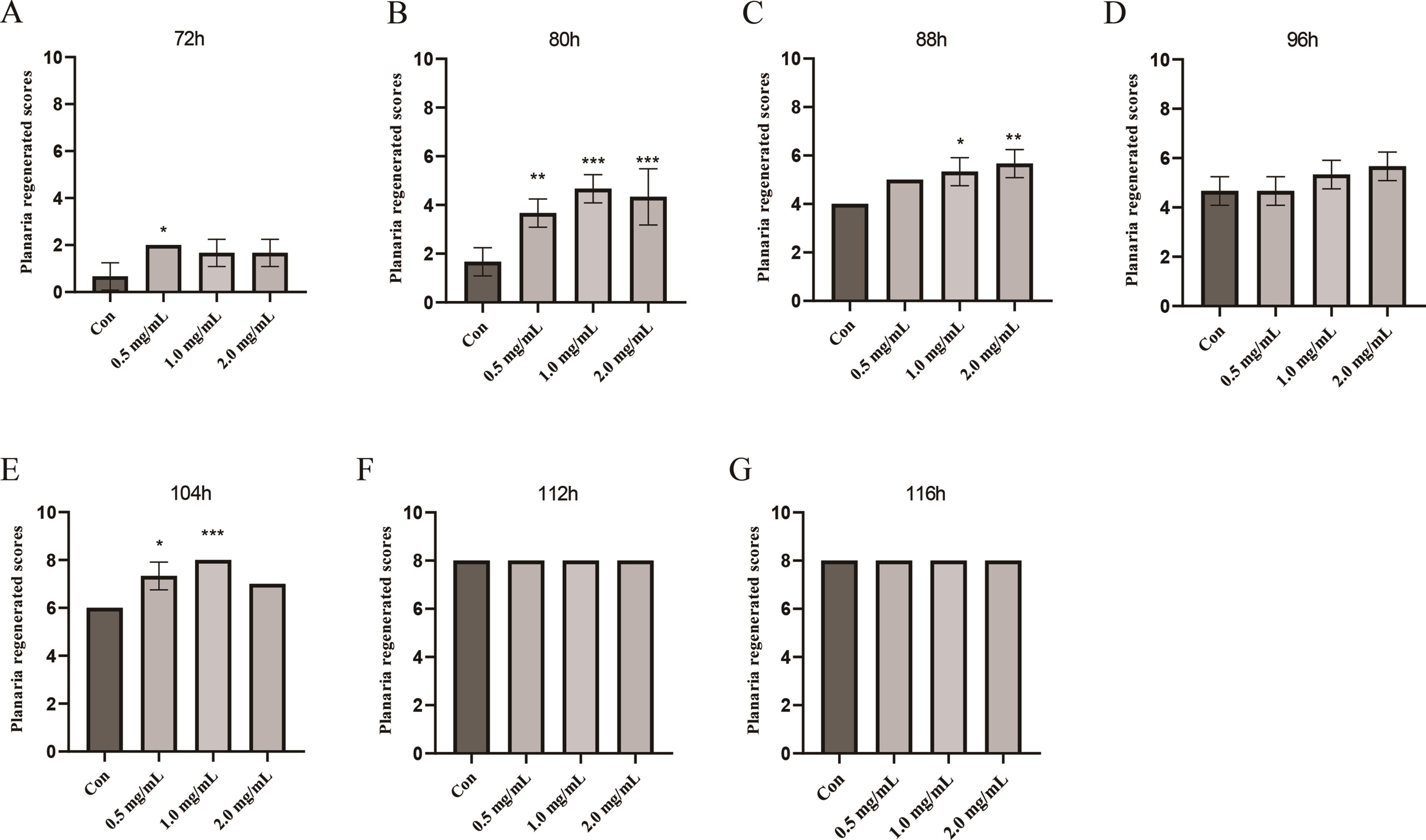

For the QFY polysaccharides, the regeneration experiments were carried out in the concentrations 0 mg/mL(con), 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL. The photos of planaria before and after decapitating are shown in Figure 4. The score range of planaria regeneration was set at 0–1 modified from Henderson and Eakin 1959 (Figure 5). The regeneration scores of 0.5 mg/mL group were higher than in the control group at 72 h, while there was no significant difference in 1.0 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL group (Figure 6A). With the extension of time, the regeneration scores of all groups were improved. At 80 h, 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL group were all higher than the control group (Figure 6B, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.001). At 88 h, 1.0 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL group were all higher than in the control group (Figure 6C, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). At 104 h, 0.5 mg/mL and 1.0 mg/mL differed significantly from the control group (Figure 6E, p < 0.05, p < 0.001). All the planaria formed complete heads within 112 h after decapitation. The results showed that the 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL polysaccharides promoted the regeneration of the head of planaria.

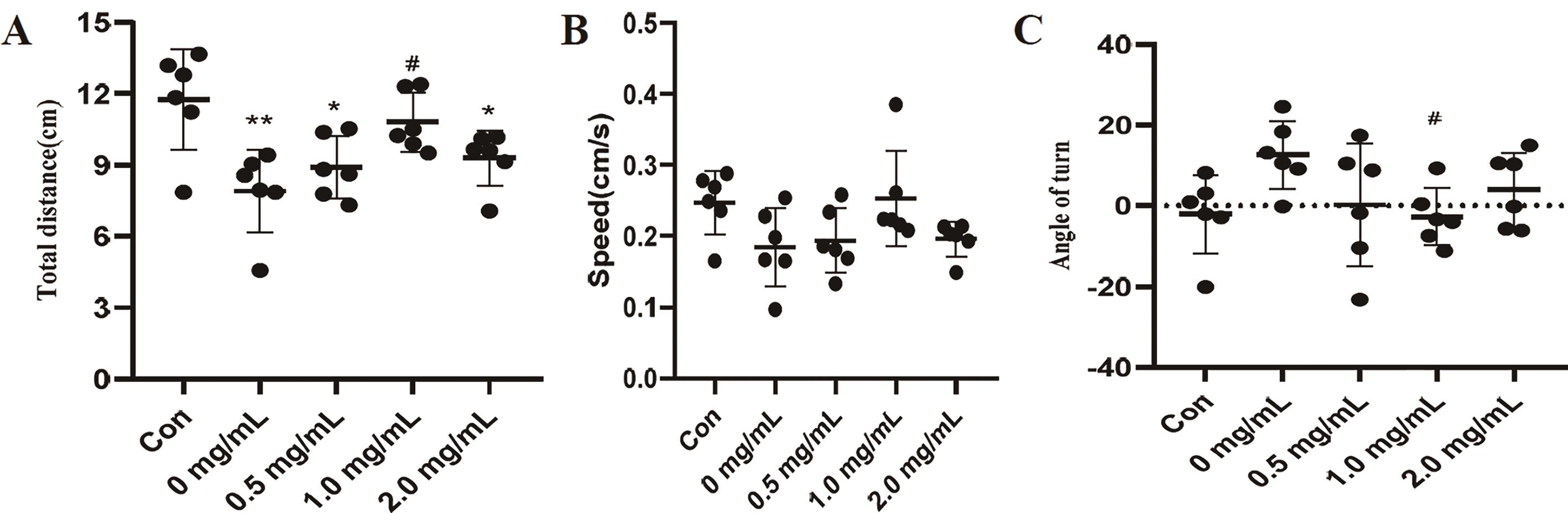

3.5.Free Swimming Behavior Test of the Post-Regenerated Planaria

The decapitated planaria were cultured in QFY polysaccharide solutions of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/mL concentration for six days. The planaria had regenerated completely when viewed with eyes. Further investigation is needed to assess whether the planaria head fully regained its functional capacity. Therefore, we tested the free-swimming behavior of planaria. The results are shown in Figure 7. The control group was intact planaria without decapitating. Compared with the control group, the total distance of post-regenerated planaria of 0, 0.5, 2.0 mg/mL group was significantly decreased (Figure 7A). The total distance was not significantly different between the 1.0 mg/mL group and the control group, but it was significantly higher compared with 0.0 mg/mL group. There was no significant difference in the speed of planaria in all groups (Figure 7B). Compared with the control group, there was no significant change in the turned angle of planaria in each group. Compared with 0 mg/mL group, the turned angle of 1.0 mg/mL group was significantly reduced (Figure 7C). The movement track diagram of the post-regenerated planaria is shown in Figure 8. These results indicated that 1.0 mg/mL polysaccharides not only promoted the regeneration of the head of planaria, but also promoted the recovery of the head function.

4.Discussion

Hydrothermal extraction and alcohol precipitation are the traditional extraction methods for polysaccharides from TCM. To improve the extraction rate of polysaccharides, ultrasonic-assisted extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction and microwave-assisted extraction methods have been developed [17,18]. These extraction methods have been used for extraction of single medicinal polysaccharide from QFY [16,42]. To explore the active substance basis of QFY, we still choose the traditional hydrothermal extraction and alcohol precipitation to prepare polysaccharides. Here, we successfully prepared QFY polysaccharides with a 29.9% yield. The high polysaccharide extraction rate was due to the high sugar content of the medicine itself, and honey was added in the processing of the medicine. Of course, there are also impurities in the extracted polysaccharide, and the purity of the polysaccharide is about 70%.

Polysaccharide from TCM and single herb showed anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, anti-cancer and other biological activities. Similarly, it has been reported that the polysaccharides from the herb of QFY also showed anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor anti-cancer activity [11,12]. Here, we found that QFYP could scavenge DPPH, ABTS+, and O2- radicals, while chelating Fe2+. This is consistent with the reported anti-oxidant activity of ginseng polysaccharide [42]. QFY polysaccharides can enhance the regeneration score of decapitated planaria and improve their post-regeneration locomotor abilities. This indicated that QFY polysaccharide can promote the regeneration of the functional head in planaria. It was crucial in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. Mechanistically, the QFY polysaccharide can promote the head or nerve regeneration of planaria by reducing oxidative stress and promoting the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells of planaria. However, the specific mechanism needs to be studied.

In this study, we selected planaria to test the regenerative activity for the following four reasons: (1) Planaria has a strong regenerative ability and can regenerate any missing part of the body, especially the head regeneration was more attractive. (2) The head of planaria contains a nerve cluster analogous to the central nervous system (CNS), making it ideal for investigations on neuro-regenerative activity. (3) Planaria has a short regeneration cycle, and can regenerate into a complete individual within 7 days, and the experiment cycle was short. (4) Planaria are small in size and easy to breed and cultivate. The advantages of using this model include its ability to screen a large number of compounds for active substances that promote regeneration, particularly nerve regeneration. This approach allows for the identification of promising candidates before advancing to more complex animal models, such as mice, thus saving both time and financial resources. Among the limitations of using this model is that planarians are invertebrates and thus, substances that are effective in planaria may not achieve similar effects on higher animals. However, this phenomenon cannot be avoided even in mouse models.

Planarians have a strong ability to regenerate. In our experiments, we found that decapitated planarians can regenerate its entire head within seven days. This was consistent with those reported in the literature. Planarians have been extensively studied, such as research on the regulatory mechanism of regeneration [21–24], neoblasts [25–27], neurotoxicology [28,32] and screening of regenerative drugs [33–35] using planaria as a model. Analysis of the phenotype has revealed that the head of the planaria can be completely regenerated, but whether its function is restored is not known. In this study, the regenerated planaria were tested for free swimming behavior to observe the function of new head.

5.Conclusions

We obtained QFY polysaccharides by hydrothermal extraction and alcohol precipitation, and separated through the DEAE-52 cellulose column chromatography. The in vitro anti-oxidant assay demonstrated that QFYP had superior scavenging activities on DPPH, ABTS+, O2- radicals and chelating activities of Fe2+. QFYP can significantly promote head regeneration and recovery of the head function in planaria. This suggests that QFYP might be used to treat AD and planarian can be used as a model for screening and evaluating compounds for AD.

Author Contributions: Xiaorui, Cheng conceived and supervised the project. Yuexiao, Zou did most of the experiments. Shixue, Wang assisted in part of the experiments. Qingxian, Wang analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82374062), and Shandong Province Technology Innovation Guidance Program (Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Funds) Project (YDZX2023003, YDZX2023137).

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations: CNS: Central nervous system, DPPH: 2,2-Di(4-tert-octylphenyl)-1-picrylhydrazyl, free radical; ABTS+: 2, 2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonicacid; O2-: Superoxide radical; IC50: half maximal inhibitory concentration; EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; NBT: Nitrotetrazolium Blue chloride; NADH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PMS: Phenazine methosulfate.

References

- 1.

Lj, A; Mq, A; Yue, F.A; et al. Dementia in China: epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 81–92.

- 2.

Better, M.A. 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’S Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695.

- 3.

Ong, W; Wu, Y; Farooqui, T; et al. Qi Fu Yin-a Ming dynasty prescription for the treatment of dementia. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 7389–7400.

- 4.

Wang, S; Liu, J; Ji, W; et al. Qifu-Yin attenuates AGEs-induced Alzheimer-like pathophysiological changes through the RAGE/NF-κB pathway. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2014, 12, 920–928.

- 5.

Xiao, Q; Wang, X; Qi, D; et al. Research progress of Qifuyin decoction and its additive prescription in treating dementia. Mil. Med. Sci. 2019, 43, 391–396.

- 6.

Wang, G. Treatment of 33 cases of Alzheimer’s disease with sea of marrow emptiness treated by thumbtack needling combined with Qifu Yin. Zhejiang J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 53, 205.

- 7.

Li, J; Liang, P; Clinical observation of Qifuyin decoction plus minus combined with memantine hydrochloride in treating moderate and severe Alzheimer’s disease. J. Med. Theory Pract. 2020, 33, 3180–3182.

- 8.

Wang, S; Huang, J; Chen, Y; et al. Qifuyin activates the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling and ameliorates synaptic injury and oxidative stress in APP/PS1 mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 333, 118497.

- 9.

Yang, X; Ye, T; He, Y; et al. Qifuyin attenuated cognitive disorders in 5×FAD mice of Alzheimer’s disease animal model by regulating immunity. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1183764.

- 10.

Xiao, Q; Ye, T; Wang, X; et al. Effects of Qifuyin on aging of APP/PS1 transgenic mice by regulating the intestinal microbiome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1048513.

- 11.

Wang, D; Shao, S; Zhang, Y; et al. Insight into polysaccharides from Panax ginseng C. A. meyer in improving intestinal inflammation: Modulating intestinal microbiota and autophagy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 683911.

- 12.

Huang, J; Liu, D; Wang, Y; et al. Ginseng polysaccharides alter the gut microbiota and kynurenine/tryptophan ratio, potentiating the antitumour effect of antiprogrammed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) immunotherapy. Gut 2022, 71, 734–745.

- 13.

Li, C; Tian, Z; Cai, J; et al. Panax ginseng polysaccharide induces apoptosis by targeting Twist/AKR1C2/NF-1 pathway in human gastric cancer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 103–109.

- 14.

Wang, J; Zuo, G; Li, J; et al. Induction of tumoricidal activity in mouse peritoneal macrophages by ginseng polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2010, 46, 389–395.

- 15.

Cai, J; Wu, Y; Li, C; et al. Panax ginseng polysaccharide suppresses metastasis via modulating Twist expression in gastric cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 57, 22–25.

- 16.

Li, C; Cai, J; Geng, J; et al. Purification, characterization and anticancer activity of a polysaccharide from Panax ginseng. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 968–973.

- 17.

Nai, J; Zhang, C; Shao, H; et al. Extraction, structure, pharmacological activities and drug carrier applications of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 2337–2353.

- 18.

Simayi, Z; Rozi, P; Yang, X; et al. Isolation, structural characterization, biological activity, and application of Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides: Systematic review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 387–398.

- 19.

Feng, Z; Yang, R; Wu, L; et al. Atractylodes macrocephala polysaccharides regulate the innate immunity of colorectal cancer cells by modulating the TLR4 signaling pathway. Oncotargets Ther. 2019, 12, 7111–7121.

- 20.

Agata, K; Soejima, Y; Kato, K; et al. Structure of the planarian central nervous system (CNS) revealed by neuronal cell markers. Zool. Sci. 1998, 15, 433–440.

- 21.

Reddien, P. The cellular and molecular basis for planarian regeneration. Cell 2018, 175, 327–345.

- 22.

Pascual-Carreras, E; Marín-Barba, M; Castillo-Lara, S; et al. Wnt/β-catenin signalling is required for pole-specific chromatin remodeling during planarian regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 298.

- 23.

Kang, J; Chen, J; Dong, Z; et al. The negative effect of the PI3K inhibitor 3-methyladenine on planarian regeneration via the autophagy signalling pathway. Ecotoxicology 2021, 30, 1941–1948.

- 24.

Harrath, A; Aldahmash, W; Alrezaki, A; et al. Using autophagy, apoptosis, cytoskeleton, and epigenetics markers to investigate the origin of infertility in ex-fissiparous freshwater planarian individuals (nomen nudum species) with hyperplasic ovaries. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023, 199, 107935.

- 25.

Fan, Y; Chai, C; Li, P; et al. Ultrafast distant wound response is essential for whole-body regeneration. Cell 2023, 186, 3606–3618.

- 26.

Park, C; Owusu-Boaitey, K; Valdes, G; et al. Fate specification is spatially intermingled across planarian stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7422.

- 27.

Cui, G; Dong, K; Zhou, J; et al. Spatiotemporal transcriptomic atlas reveals the dynamic characteristics and key regulators of planarian regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3205.

- 28.

Gao, T; Sun, B; Xu, Z; et al. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics reduces regeneration and growth in planarians. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128673.

- 29.

Lowe, J.R; Mahool, T.D; Staehle, M.M; Ethanol exposure induces a delay in the reacquisition of function during head regeneration in Schmidtea mediterranea. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2015, 48, 28–32.

- 30.

Ofoegbu, P.U; Lourenço, J; Mendo, S; et al. Effects of low concentrations of psychiatric drugs (carbamazepine and fluoxetine) on the freshwater planarian, Schmidtea mediterranea. Chemosphere 2019, 217, 542–549.

- 31.

Effects of bisphenol A, M; japonica, Dugesia; . Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2015, 96, 1174–1184.

- 32.

Pagán, O.R; Rowlands, A.L; Urban, K.R; Toxicity and behavioral effects of dimethylsulfoxide in planaria. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 407, 274–278.

- 33.

Han, Y; Chen, D; Xu, Z; et al. The screening model of pro-regenerative drugs was constructed by using head regeneration of planaria. For. By-Prod. Spec. China 2017, 5, 1–5.

- 34.

Xu, Z.; Song, L. Planaria: A model organism for screening regenerative and senescence related drugs in vivo. Chin. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 38, 744–749.

- 35.

Zhou, Y; Yan, M; Gao, L; et al. Reseach on animal models of aging and its application in screening the activity of anti-aging drugs. Chin. Herb. Med. 2017, 48, 1061–1071.

- 36.

Holtze, S; Gorshkova, E; Braude, S; et al. Alternative animal models of aging research. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 660959.

- 37.

Henry, J; Wlodkowic, D; Towards high-throughput chemobehavioural phenomics in neuropsychiatric drug discovery. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 340.

- 38.

Sugahara, S; Ueda, Y; Fukuhara, K; et al. Antioxidant effects of herbal tea leaves from yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) on multiple free radical and reducing power assays, especially on different superoxide anion radical generation systems. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, 2420–2429.

- 39.

Shi, K; Yang, G; He, L; et al. Purification, characterization, antioxidant, and antitumor activity of polysaccharides isolated from silkworm cordyceps. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13482.

- 40.

Ju, Y; Xue, Y; Huang, J; et al. Antioxidant Chinese yam polysaccharides and its pro-proliferative effect on endometrial epithelial cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 81–85.

- 41.

Inoue, T; Agata, K; Quantification of planarian behaviors. Dev. Growth Differ. 2022, 64, 16–37.

- 42.

Chen, F; Huang, G; Antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from different sources of ginseng. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 906–908.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.