Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia. The main cause of mortality in DM patients is cardiovascular disease. Patients with DM have a higher incidence of developing heart failure (HF), especially due to diabetic cardiomyopathy (DC). At the earlier stage, patients might be asymptomatic, yet it may develop to HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as it progresses. However, its essentiality is usually underestimated. DC is portrayed by increased thickness of the ventricular septal and left posterior myocardial wall. Its pathogenesis is complicated and involves numerous pathways initiated by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia, which contribute to the cardiac hypertrophy. By recognizing the importance of DC and its pathogenesis, the prognosis can be better comprehended, and new therapeutic targets could be better explored in the future.

- Open Access

- Review

The Underestimated Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Its Role in Heart Failure Progression and Implications for Drug Discovery

- Felycia Fernanda Hosyanto 1,

- Jiang Min 2,*,†,

- Suxin Luo 1,*,†,

- Shenglan Yang 1,*,†

Author Information

Received: 17 Oct 2024 | Revised: 18 Nov 2024 | Accepted: 19 Nov 2024 | Published: 27 Aug 2025

Abstract

Keywords

1.Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one chronic metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia due to the disorder in insulin secretion and/or function [1]. The global prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 529 million in 2021 [2], which is estimated to be more than 783.2 million individuals by 2045 [3]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) takes a proportion of more than 90% of patients diagnosed with DM [4]. Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of mortality in individuals with DM and two-third of mortalities is T2DM patients [5]. Diabetic patients have a higher risk of developing HF (39%) compared to non-diabetic patients (23%) [6]. Framingham Heart Study (1974) demonstrated that diabetic women have higher incidence to develop HF compared to men [7]. According to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), 1% reduction of HbA1c will lead to a 16% reduction in the HF development [8]. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients’ incidence to develop HF is higher than that of T2DM, independent of other risk factors. An increase of 1% HbA1c in T1DM causes a 30% increase in HF risk [9], while it is 8% increased risk of HF for every increased 1% HbA1c in T2DM patients [8]. Not all diabetic patients develop HF and not all HF patients have DM, yet DM is critical for the development of HF [10,11]. Diabetic patients who develop HF will have the clinical manifestations of both DM and HF. DM can progress to HF through vasculopathy, ischemic cardiomyopathy, and diabetic cardiomyopathy (DC). Myocardial ischemia resulted from both micro- and macro-vasculopathy will deteriorate the myocardial function, leading to HF, and this could be commonly alerted [12]. However, the non-ischemia cardiomyopathy, which is called diabetic cardiomyopathy, essentially contributing to cardiac dysfunction of diabetes, is always underestimated.

2.Clinical Manifestations of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DC) is defined as the pathophysiological condition—structure and function—of the heart due to DM in the absence of other etiologies and risk factors, such as coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension, and valvular disease. HF may follow at a late stage despite its asymptomatic condition in the earliest stage of the diabetes [13]. This term has been used since 1972 [14], yet it is still underappreciated. DC is common in diabetic individuals but is often underestimated due to the absence of symptoms and signs in the early stage [15].

According to several studies, in DC patients attributed to T1DM, the diastolic function impairment is frequent [16] and with earlier onset [17] than systolic function impairment. However, according to Tan et al., T1DM patients manifest more with the symptoms of systolic dysfunction [18]. Nevertheless, DC is the major cause of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). DC associated with T2DM is characterized by: (1) declined ventricular compliance; (2) increased systemic and pulmonary venous pressures and congestion; (3) HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) with diastolic dysfunction [19]. The left ventricular mass index is increased by 6–9% and by 12–14% in females and males with T2DM, respectively [8]. Hence, there is a positive relationship between T2DM and left ventricular wall thickness [8,20]. Stahrenberg et al. demonstrated that the severity and prevalence of diastolic dysfunction deteriorate as T2DM progresses, observed in the poorer diastolic parameters in diabetic patients in comparison with non-diabetic patients [21].

The clinical manifestations of DC are classified into three stages [13]. The first stage is mostly asymptomatic, characterized by increased cardiac fibrosis and stiffness. This hidden subclinical period presents with impaired diastolic filling, enhanced atrial filling, and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure [22]. The second stage of DC is characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac remodeling, deterioration of diastolic dysfunction, and HFpEF [23]. At a late stage, patients present with enlarged left ventricular chambers, HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), as well as dysfunction of both systolic and diastolic functions. Pre-ejection performance will be prolonged with shortened ejection duration. As it progresses, filling resistance and filling pressure develops [23].

Cardiac hypertrophy is a typical structural change in the pathophysiological progression of DC, which is portrayed by ventricular septal and left posterior myocardial wall thicknesses due to compromised systolic or diastolic function [24].

3.Mechanisms of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

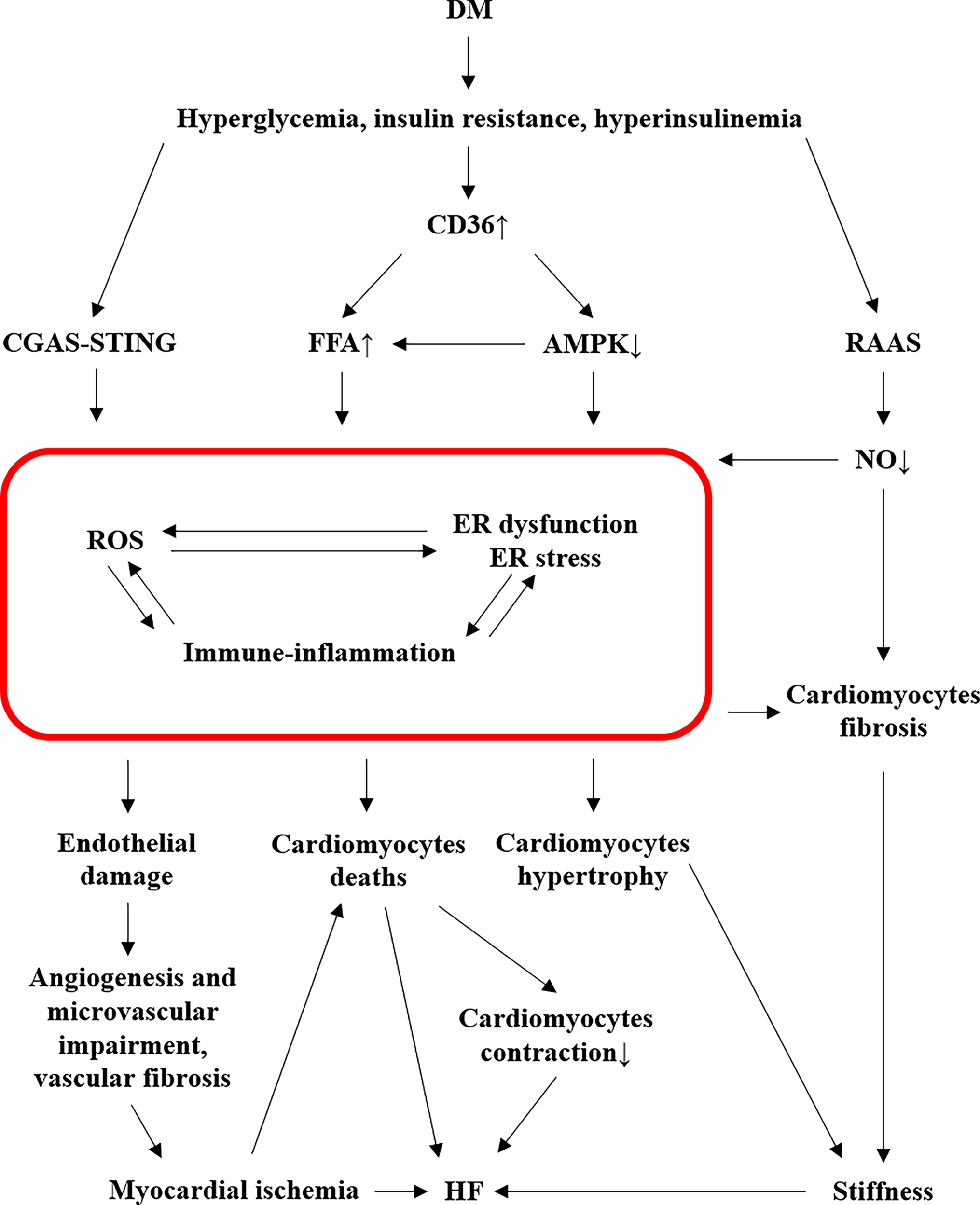

The pathogenesis of DC is complicated, which involves numerous pathways initiated by abnormal metabolism, such as hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia, that all contribute to the cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 1).

3.1.Roles of Free Fatty Acid in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

DM induces increased free fatty acid (FFA) release from adipose tissue and enhances the capacity of myocyte sarcolemmal FFA transporters due to the increased cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36), an essential membrane protein which promotes FFA uptake, in diabetic hearts [23,25]. CD36 also plays a significant role in mediating adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway activation by diminishing its activity. DM attenuates the activation of AMPK, resulting in increased FFA uptake into the heart, triacylglycerol accumulation, and diminished utilization of glucose [26]. Consequently, FFAs accumulate in the diabetic heart as a response to maintain sufficient ATP production [18]. As time goes by, the accumulating FFAs become excessive and not able to be metabolized, also called β-oxidation, adequately, finally resulting in cardiac lipotoxicity and various detrimental consequences. Over FFA oxidation, together with advanced glycation end products (AGEs), gives rise to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to mitochondrial damage [18]. Meanwhile, excessive lipid metabolites, e.g., diacylglycerol, promote endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Besides, PKC signal is activated by increased DAGs in response to excessive free fatty acids [27]. Protein kinase C (PKC), which is associated with diacylglycerols (DAGs), contributes to DC [13].

3.2.Mitochondrial Damage in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Mitochondrial damage plays a key role in the development of DC [28]. DM causes the switch of mitochondrial main metabolic substrate from glucose to FFA [23]. In DM, FFA oxidation, AGEs, RAAS overactivation, and impaired oxidative phosphorylation all together will cause mitochondrial impairment. This mitochondrial damage induces oxidative stress, alters mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, leading to cardiomyocytes apoptosis, endothelial damages, and microvascular alteration [18]. Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction also promotes ER stress and inflammation, which in turn promote oxidative stress [23]. Mitochondrial injury is also tightly correlated with the alteration of the four essential genes: Pdk, Hmgcs2, Decr1 (up-regulated), Ivd (down-regulated), that are further involved in the inflammation pathway [29]. Thereby, mitochondrial injury is the intersection point of oxidative stress, ER stress, and inflammation, deteriorating the cardiac function of diabetes.

3.3.Inflammation in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Mitochondrial metabolism and immune-inflammation are key for DC pathogenesis, and several mitochondrial pivotal genes are implicated in diabetic inflammatory conditions. For example, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (Hmgcs2), and 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase 1 (Decr1) are up-regulated, while isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (Ivd) is down-regulated [29]. These four genes are essential in the metabolic process of mitochondria. Pdk4, which regulates pyruvate oxidation through the phosphorylation and inhibition of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC), an important control point in glucose and pyruvate metabolism, is strongly correlated with fatty acid oxidation and insulin resistance, and it has been proven to regulate B cells and M2 macrophages [29]. Hmgcs2 associated with ketogenesis, also has positive association with B cells [29]. It can be used to predict the DC outcome, progression, and prognosis [30]. Its essential role in the degradation of poly-unsaturated fatty acids is shown to have a positive relationship with B cells and M2 macrophages [29]. Elevated B cells level in DM contributes to pro-inflammatory environment [31]. Ivd is beneficial towards cardiac injury [32], but its expression is declined in DC [29]. Moreover, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is noticed to be raised in diabetic condition [33], along with increased ventricular infiltration of T cells [34] and M1 macrophages potentiated the secretion of inflammatory factors to induce insulin resistance [35]. DM also increases the chemical non-enzymatic AGEs formation that initiates the inflammation response, producing ROS, and cross-linking with extracellular matrix [13,23].

In DM, cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) could activate stimulator of interferon genes (STING). cGAS is a key cytosolic sensor [36] which is sensitive to immunological changes by inducing proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., IL-6 and TNF-a, via the transcription factor nuclear factor kB (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) [37], partaking in the oxidative stress and inflammation process in DM. STING is a primary transmembrane protein that mediates the activation of low-grade inflammation, such as aging, HF, and DM [38–40]. In diabetic heart, the cGAS-STING pathway is activated in inflammation manner, due to the escaped mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol, elevating the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3), and NLRP3 will induce cardiac pyroptosis and further promote chronic inflammation, hence contributing to the progression of DC [40].

3.4.Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and AMPK in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Excessive ROS and nitric oxide (NO), as well as the existence of inflammation, will be followed by cardiac endoplasmic reticulum (ER) dysfunction and ER stress [24,41]. These conditions are mutually reinforcing [18]. In diabetic heart, lipid metabolites such as diacylglycerol contribute to ER stress [13]. ER stress enhances cellular apoptosis and autophagy [24], and decreases the expression of sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) which will further damage cardiomyocyte contraction [13,42].

AMPK signaling pathway is notably restrained in diabetic conditions, boosting autophagy and apoptosis. Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) also regulates autophagy, wherein its suppression will facilitate the initiation of autophagy [43]. Both autophagy and apoptosis play a pivotal role in the pathogeneses of DC. In addition to autophagy, impaired AMPK activation will suppress the expression and translocation of GLUT4 and thus insulin-induced glucose uptake [44]. In contrast, the activation of AMPK will enhance the glucose uptake [45], as it causes the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters towards the cell surface [46]. Therefore, the down-regulated AMPK pathway promotes the DC.

3.5.Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Accumulation of ROS plays a crucial role in the process of DC, which promotes the expression of numerous cardiomyocyte hypertrophic genes, such as β-myosin heavy chain, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) [47]. Hyperglycemic condition will cause the binding of the excessive glucose to IGF-1, which contributes to DC via insulin receptor, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathways [48]. The expression of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX), a vital source of cardiomyocyte ROS, is increased in diabetic conditions [49]. Redundant NOX would undergo the RAAS pathway in addition to the respiratory chain, that is angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress, by activating growth factor β1/Smad 2/3 signaling pathway [49–51]. Activated xanthine oxidase and microsomal P-450 enzyme activity, as well as NO synthase uncoupling are also associated with the increased amount of ROS and downstream PKC signaling [41]. Both the decreased amount of NO and the activated PKC signaling are closely related to ROS pathway, contributing to the generation of DC.

Excessive ROS that result in the reduced NO bioavailability suppresses the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) activity and cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels, leading to the loss of the protective effects of protein kinase G (PKG) that then triggers the endothelial microvascular inflammation reaction [18], resulting in angiogenesis impairment in the development of DC [52].

Impaired glucose metabolism is another cause of abnormal RAAS pathway [13], leading to impairment of NO production, which further increases the collagen cross-linking enzymes activation, i.e., transglutaminase [53]. In addition to RAAS pathway, NF-κB contributes to the reduced NO bioavailability [54]. Consequently, overexpression of collagen in cardiomyocytes, along with the crosstalk between IGF-1 and cardiac insulin signaling pathway, contribute to the reconstruction of DC [13].

3.6.Cardiac Remodeling in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Cardiac Fibrosis and Hypertrophy

Diabetic condition will enhance the synthesis of molecules involved with collagen deposition. For instance, inflammation cytokines, connective tissue growth factor, metalloproteinases, and galectin-3, which are all recognized as collagen biomarkers, and overexpression of collagen biomarkers in cardiomyocytes could lead to cardiac fibrosis [55]. DM disturbs the NO production, which further activates the collagen cross-linking enzymes, such as transglutaminase, and this process is involved in the diabetic cardiac fibrosis [53]. Besides, endothelial and epicardial cells also lead to cardiac fibrosis via endothelial-to-mesenchymal or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition to myofibroblasts, in addition to cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts [56–58].

Oxidative stress, inflammation, and ER stress contribute to a progressive profibrotic response that induces cardiac hypertrophy and extracellular matrix (ECM) fibrosis [18]. Meanwhile, inflammatory cytokines and protein kinase are evidenced to directly cause cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, thereby promoting cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [59,60], resulting in cardiac dysfunction: diastolic and/or systolic dysfunction [18]. In this regard, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis are typical features in the remodeling of diabetic heart.

3.7.Other Pathways Implicated in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

A variety of biomolecular pathways in addition to those discussed above have also contributed to the development of DC, for instance, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate-responsive element modulator (CREM), microRNAs (miRNA), lcRNA, and exosomes. Moreover, fructose also has a role in the pathogenesis of DC.

PPARs participate in the metabolism of glucose and fatty acid, and are activated via the direct impacts of increased FFA uptake and mitochondrial FFA oxidation in DM, deteriorating the cardiac function [61]. The up-regulated O-GlcNAc induced by DM impairs mitochondrial function and insulin metabolic signaling, which further induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis [62]. In physiological condition, SGLT1 is the predominant active glucose transporter from the gastrointestinal lumen into the gastrointestinal epithelium, and SGLT2 is primarily expressed in the kidneys [63]. However, in diabetic conditions, SGLT2 is overexpressed due to the glomerular hyperfiltration, increased glucose reabsorption, and elevated plasma glucose [64], and upregulated SGLT2 is evidenced to promote vascular stiffness [64] and mitochondrial dysfunction [65]. Therefore, it can reduce the blood glucose level independently to insulin [66], and SGLT2 inhibitors have been actively used in the clinic as the effective treatment of both HF and DM patients. Nrf2 is a transcription factor responsible for oxidative stress and inflammation [67]. DM will thereby induce Nrf2 activation, which primarily binds to its inhibitor, Keap1, to prevent excessive cellular Nrf2 [68], resulting in decreased Nrf2. A potential therapeutic target is obtained by restoring Nrf2 function, as is found to prevent DM–induced lipotoxicity, inflammation, fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction [69]. CREM is an indispensable regulator of cardiac cAMP signaling. Its expression is aggravated in diabetic condition, contributing to abundant FFA accumulation and cardiac fibrosis [70], due to the sequent changes in histone acetylation and disorder of miRNAs in DM.

miRNAs have been implicated in diverse physiological and pathological processes, including cardiac pathology in diabetes, such as ROS over-production, mitochondrial impairment, abnormal Ca2+ handling, enhanced apoptosis, excessive autophagy, and fibrosis [71,72]. miR-34a has been proven to be a key miRNA in DC. The expression of miR-34a is decreased in the hypertrophic phase of myocardial remodeling but is increased in HF stage [73]. It inhibits the autophagy via the suppression of ATG9A expression, a protein essential for autophagy and lipid homeostasis [74,75]. Meanwhile, as angiotensin II is associated with cardiac hypertrophy and autophagy [76], its down-regulation via miR-34a can be a novel therapeutic target for cardiac hypertrophy in the future.

Exosome an extracellular vehicle for cellular activities [22]. The lately, research showed that in diabetic heart, exosomes with abundant miR-320 are released from cardiomyocytes and transported to coronary endothelial cells for downstream regulation [77]. It will decrease the NO production and vitiate angiogenesis by decreasing heat shock protein 20. Conversely, heat shock protein 20–engineered exosomes can restore the cardiac function impairment due to DM [78]. Hence, exosomes can function as both biomarkers of DM-induced disruptions and potential therapeutic target. In addition, miR-320 is found to trigger the CD36 transcription, which is essential in FFA oxidation [79].

According to numerous studies, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) is said to be correlated with the tumorigenesis by the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism [80–82], wherein the glucose metabolism is closely related to the glucose transporters (GLUTs) [82]. One study regarding the lncRNA in DC found that the level of lncRNA NKILA expression was elevated in the plasma of DC patients. These molecules have the potential of inducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and are potential diagnostic as well as therapeutic targets in the future [83].

High levels of fructose can provoke autophagy, enhancing phosphorylation that further diminishes the synthesis of ATP. This will lead to the up-regulation of O-GlcNAc and AGE production, reducing the amount of NO produced [84,85], and promoting cardiac fibrosis in the end [86].

It is important to recognize the predominant role of DC in HFpEF in the diabetes, which is often neglected. Accounting for the complicated and overlapping signal pathways in the pathogenesis of DC, the prognosis could be better comprehended and new therapeutic targets might be better explored in the future.

4.Conclusions

Patients with DM have a higher incidence of developing heart failure (HF) via diabetic cardiomyopathy (DC). Patients tend to be asymptomatic at the early stage but will develop into HFpEF along with its progression, becoming HFrEF at the late stage. Its pathogenesis involves various pathways that lead to the hypertrophy of the ventricular septum and left posterior myocardial wall, and can progress to HF at the end stage. It should be noted that the significance of DC is often neglected. According to the current pathogenesis of DC, potential effective treatment targets can be obtained. For instance, metformin and SGLT2i can protect the heart through AMPK and SGLT2 pathways, respectively [13]. Therefore, exploring the pathogenesis of DC is of great significance.

Author Contributions: F.F.H.: writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing, visualization; J.M.: writing—reviewing and editing, funding acquisition; S.Y.: conceptualization, writing—reviewing and editing, supervision, funding acquisition; S.L.: writing—reviewing and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0290, cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0288).

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.

Darenskaya, M.A; Kolesnikova, L.I; Kolesnikov, S.I; Oxidative Stress: Pathogenetic Role in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications and Therapeutic Approaches to Correction. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10517-021-05191-7.

- 2.

GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6.

- 3.

Sun, H; Saeedi, P; Karuranga, S; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119.

- 4.

American Diabetes, A. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl. 1), S14–S80. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-S014.

- 5.

Diabetic Cardiomyopathy, W.H; . Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1160–1162. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314665.

- 6.

Aronow, W.S; Ahn, C; Incidence of heart failure in 2737 older persons with and without diabetes mellitus. Chest 1999, 115, 867–868. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.115.3.867.

- 7.

Kannel, W.B; Hjortland, M; Castelli, W.P; Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. Am. J. Cardiol. 1974, 34, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(74)90089-7.

- 8.

Devereux, R.B; Roman, M.J; Paranicas, M; et al. Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: The strong heart study. Circulation 2000, 101, 2271–2276. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.101.19.2271.

- 9.

Lind, M; Bounias, I; Olsson, M; et al. Glycaemic control and incidence of heart failure in 20,985 patients with type 1 diabetes: An observational study. Lancet 2011, 378, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60471-6.

- 10.

Lee, S.E; Lee, H.Y; Cho, H.J; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Acute Heart Failure in Korea: Results from the Korean Acute Heart Failure Registry (KorAHF). Korean Circ. J. 2017, 47, 341–353. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.0419.

- 11.

Park, J.J; Choi, D.J; Current status of heart failure: Global and Korea. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2020.120.

- 12.

Epidemiology, J.J; . Diabetes Metab. J. 2021, 45, 146–157. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0282.

- 13.

Jia, G; Hill, M.A; Sowers, J.R; Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Mechanisms Contributing to This Clinical Entity. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 624–638. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311586.

- 14.

Rubler, S; Dlugash, J; Yuceoglu, Y.Z; et al. New type of cardiomyopathy associated with diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 1972, 30, 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(72)90595-4.

- 15.

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Association of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity With Mortality. JAMA 2015, 314, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.7008.

- 16.

Raev, D.C. Which left ventricular function is impaired earlier in the evolution of diabetic cardiomyopathy? An echocardiographic study of young type I diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1994, 17, 633–639. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.17.7.633.

- 17.

Berkova, M; Opavsky, J; Berka, Z; et al. Left ventricular diastolic filling in young persons with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pap. 2003, 147, 57–61. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2003.008.

- 18.

Tan, Y; Zhang, Z; Zheng, C; et al. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: Preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0339-2.

- 19.

Holscher, M.E; Bode, C; Bugger, H; Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Does the Type of Diabetes Matter? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17122136.

- 20.

Eguchi, K; Boden-Albala, B; Jin, Z; et al. Association between diabetes mellitus and left ventricular hypertrophy in a multiethnic population. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, 1787–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.082.

- 21.

Stahrenberg, R; Edelmann, F; Mende, M; et al. Association of glucose metabolism with diastolic function along the diabetic continuum. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1331–1340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1718-8.

- 22.

Westermeier, F; Riquelme, J.A; Pavez, M; et al. New Molecular Insights of Insulin in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00125.

- 23.

Jia, G; DeMarco, V.G; Sowers, J.R; Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2015.216.

- 24.

Lee, M; Gardin, J.M; Lynch, J.C; et al. Diabetes mellitus and echocardiographic left ventricular function in free-living elderly men and women: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Am. Heart J. 1997, 133, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70245-x.

- 25.

Guo, C.A; Guo, S; Insulin receptor substrate signaling controls cardiac energy metabolism and heart failure. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 233, R131–R143. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-16-0679.

- 26.

Finck, B.N; Lehman, J.J; Leone, T.C; et al. The cardiac phenotype induced by PPARalpha overexpression mimics that caused by diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI14080.

- 27.

Atkinson, L.L; Kozak, R; Kelly, S.E; et al. Potential mechanisms and consequences of cardiac triacylglycerol accumulation in insulin-resistant rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 284, E923–E930. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00360.2002.

- 28.

Kim, J.A; Wei, Y; Sowers, J.R; Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165472.

- 29.

Peng, C; Zhang, Y; Lang, X; et al. Role of mitochondrial metabolic disorder and immune infiltration in diabetic cardiomyopathy: New insights from bioinformatics analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-03928-8.

- 30.

Song, J.P; Chen, L; Chen, X; et al. Elevated plasma beta-hydroxybutyrate predicts adverse outcomes and disease progression in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, aay8329. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aay8329.

- 31.

Adamo, L; Rocha-Resende, C; Lin, C.Y; et al. Myocardial B cells are a subset of circulating lymphocytes with delayed transit through the heart. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e134700. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.134700.

- 32.

Toneto, A.T; Ferreira Ramos, L.A; Salomao, E.M; et al. Nutritional leucine supplementation attenuates cardiac failure in tumour-bearing cachectic animals. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12100.

- 33.

Indrova, M; Bubenik, J; Generation of LAK cells depends on the age of LAK cell precursor donors. Folia Biol. 1988, 34, 48–52.

- 34.

Nevers, T; Salvador, A.M; Grodecki-Pena, A; et al. Left Ventricular T-Cell Recruitment Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 776–787. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002225.

- 35.

Lehrke, M; Reilly, M.P; Millington, S.C; et al. An inflammatory cascade leading to hyperresistinemia in humans. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e45. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0010045.

- 36.

Yu, L; Liu, P; Cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS: Regulation, function, and human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021, 6, 170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00554-y.

- 37.

Decout, A; Katz, J.D; Venkatraman, S; et al. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 548–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z.

- 38.

Gulen, M.F; Samson, N; Keller, A; et al. cGAS-STING drives ageing-related inflammation and neurodegeneration. Nature 2023, 620, 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06373-1.

- 39.

Guo, Y; You, Y; Shang, F.F; et al. iNOS aggravates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction via activation of the cytosolic-mtDNA-mediated cGAS-STING pathway. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4229–4246. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.84049.

- 40.

Yan, M; Li, Y; Luo, Q; et al. Mitochondrial damage and activation of the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS-STING pathway lead to cardiac pyroptosis and hypertrophy in diabetic cardiomyopathy mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-01046-w.

- 41.

Giacco, F; Brownlee, M; Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1058–1070. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545.

- 42.

Yang, L; Zhao, D; Ren, J; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and protein quality control in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.006.

- 43.

Talukder, M.A; Kalyanasundaram, A; Zuo, L; et al. Is reduced SERCA2a expression detrimental or beneficial to postischemic cardiac function and injury? Evidence from heterozygous SERCA2a knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H1426–H1434. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2007.

- 44.

Zou, M.H; Xie, Z; Regulation of interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in the diabetic heart: New role of AMPK. Autophagy 2013, 9, 624–625. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.23577.

- 45.

Nielsen, J.N; Jorgensen, S.B; Frosig, C; et al. A possible role for AMP-activated protein kinase in exercise-induced glucose utilization: Insights from humans and transgenic animals. Biochem Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0310186.

- 46.

Chen, Y.C; Lee, S.D; Kuo, C.H; et al. The effects of altitude training on the AMPK-related glucose transport pathway in the red skeletal muscle of both lean and obese Zucker rats. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2011, 12, 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1089/ham.2010.1088.

- 47.

Rosenkranz, A.C; Hood, S.G; Woods, R.L; et al. B-type natriuretic peptide prevents acute hypertrophic responses in the diabetic rat heart: Importance of cyclic GMP. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2389–2395. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2389.

- 48.

Sundgren, N.C; Giraud, G.D; Schultz, J.M; et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositol-3 kinase mediate IGF-1 induced proliferation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 285, R1481–R1489. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00232.2003.

- 49.

Jia, G; Habibi, J; Aroor, A.R; et al. Enhanced endothelium epithelial sodium channel signaling prompts left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in obese female mice. Metabolism 2018, 78, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.08.008.

- 50.

Lee, S.J; Kang, J.G; Ryu, O.H; et al. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid on transforming growth factor beta1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-fibronectin pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism 2009, 58, 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2008.12.006.

- 51.

Murdoch, C.E; Chaubey, S; Zeng, L; et al. Endothelial NADPH oxidase-2 promotes interstitial cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction through proinflammatory effects and endothelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2734–2741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.572.

- 52.

Wu, H; Yang, Z; Wang, J; et al. Exploring shared therapeutic targets in diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetic foot ulcers through bioinformatics analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 230. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50954-z.

- 53.

Bertoni, A.G; Goff, D.C; D’Agostino, R.B; Jr.;et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy and subclinical cardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 588–594. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1501.

- 54.

Mariappan, N; Elks, C.M; Sriramula, S; et al. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 85, 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvp305.

- 55.

Passino, C; Barison, A; Vergaro, G; et al. Markers of fibrosis, inflammation, and remodeling pathways in heart failure. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 443, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2014.09.006.

- 56.

Smith, C.L; Baek, S.T; Sung, C.Y; et al. Epicardial-derived cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fate specification require PDGF receptor signaling. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, e15–e26. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235531.

- 57.

Travers, J.G; Kamal, F.A; Robbins, J; et al. Cardiac Fibrosis: The Fibroblast Awakens. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1021–1040. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306565.

- 58.

Zeisberg, E.M; Tarnavski, O; Zeisberg, M; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 2007, 13, 952–961. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1613.

- 59.

Gordon, J.W; Shaw, J.A; Kirshenbaum, L.A; Multiple facets of NF-kappaB in the heart: To be or not to NF-kappaB. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 1122–1132. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928.

- 60.

Nakamura, M; Sadoshima, J; Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 387–407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0007-y.

- 61.

Wagner, N; Wagner, K.D; The Role of PPARs in Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9112367.

- 62.

Makino, A; Dai, A; Han, Y; et al. O-GlcNAcase overexpression reverses coronary endothelial cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 309, C593–C599. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00069.2015.

- 63.

Lehrke, M; Marx, N; Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, S37–S47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.014.

- 64.

Lytvyn, Y; Bjornstad, P; Udell, J.A; et al. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibition in Heart Failure: Potential Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Summary of Clinical Trials. Circulation 2017, 136, 1643–1658. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030012.

- 65.

SGLT, M; 2 inhibitors: Role in protective reprogramming of cardiac nutrient transport and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 443–462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00824-4.

- 66.

Hsia, D.S; Grove, O; Cefalu, W.T; An update on sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017, 24, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000311.

- 67.

He, F; Ru, X; Wen, T; NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134777.

- 68.

Niture, S.K; Khatri, R; Jaiswal, A.K; Regulation of Nrf2-an update. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 66, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.008.

- 69.

Zhang, Z; Wang, S; Zhou, S; et al. Sulforaphane prevents the development of cardiomyopathy in type 2 diabetic mice probably by reversing oxidative stress-induced inhibition of LKB1/AMPK pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 77, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.09.022.

- 70.

Barbati, S.A; Colussi, C; Bacci, L; et al. Transcription Factor CREM Mediates High Glucose Response in Cardiomyocytes and in a Male Mouse Model of Prolonged Hyperglycemia. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2391–2405. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2016-1960.

- 71.

Barwari, T; Joshi, A; Mayr, M; MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2577–2584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.945.

- 72.

Zampetaki, A; Kiechl, S; Drozdov, I; et al. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 810–817. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357.

- 73.

Huang, J; Sun, W; Huang, H; et al. miR-34a modulates angiotensin II-induced myocardial hypertrophy by direct inhibition of ATG9A expression and autophagic activity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94382. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094382.

- 74.

Mailler, E; Guardia, C.M; Bai, X; et al. The autophagy protein ATG9A enables lipid mobilization from lipid droplets. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6750. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26999-x.

- 75.

Meng, Y; Luo, Q; Chen, Q; et al. A noncanonical autophagy function of ATG9A for Golgi integrity and dynamics. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1607–1608. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2131244.

- 76.

Porrello, E.R; Delbridge, L.M; Cardiomyocyte autophagy is regulated by angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors. Autophagy 2009, 5, 1215–1216. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.5.8.10153.

- 77.

Wang, X; Huang, W; Liu, G; et al. Cardiomyocytes mediate anti-angiogenesis in type 2 diabetic rats through the exosomal transfer of miR-320 into endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 74, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.05.001.

- 78.

Wang, X; Gu, H; Huang, W; et al. Hsp20-Mediated Activation of Exosome Biogenesis in Cardiomyocytes Improves Cardiac Function and Angiogenesis in Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3111–3128. https://doi.org/10.2337/db15-1563.

- 79.

Li, H; Fan, J; Zhao, Y; et al. Nuclear miR-320 Mediates Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction by Activating Transcription of Fatty Acid Metabolic Genes to Cause Lipotoxicity in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 1106–1120. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314898.

- 80.

Corbet, C; Feron, O; Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer progression. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000381.

- 81.

Corbet, C; Pinto, A; Martherus, R; et al. Acidosis Drives the Reprogramming of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Cancer Cells through Changes in Mitochondrial and Histone Acetylation. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.003.

- 82.

Lu, W; Cao, F; Wang, S; et al. LncRNAs: The Regulator of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Tumor Cells. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.01099.

- 83.

Li, Q; Li, P; Su, J; et al. LncRNA NKILA was upregulated in diabetic cardiomyopathy with early prediction values. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 1221–1225. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2019.7671.

- 84.

Johnson, R.J; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G; Nakagawa, T; The effect of fructose on renal biology and disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 2036–2039. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010050506.

- 85.

Samuel, V.T. Fructose induced lipogenesis: From sugar to fat to insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.003.

- 86.

Delbridge, L.M; Benson, V.L; Ritchie, R.H; et al. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: The Case for a Role of Fructose in Disease Etiology. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3521–3528. https://doi.org/10.2337/db16-0682.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.