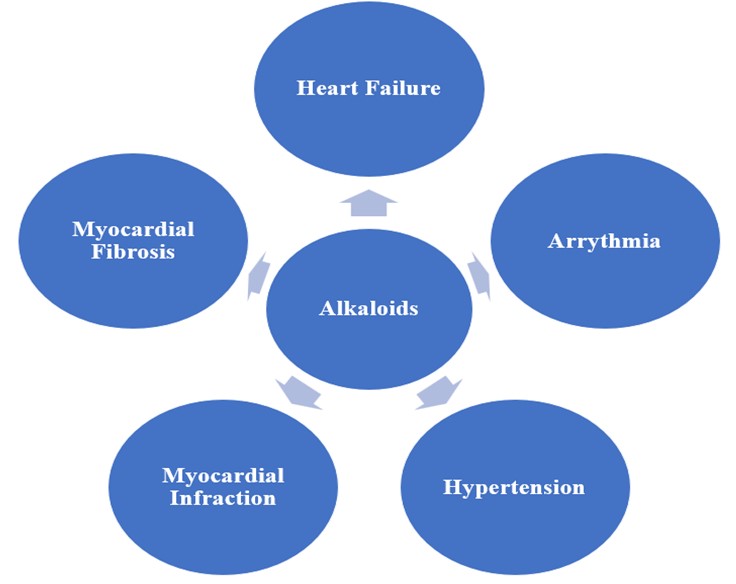

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a leading cause of death globally, particularly in low- and middle-income regions, with heart failure (HF), arrhythmia, hypertension, myocardial infarction (MI), and myocardial fibrosis among the most prominent conditions. Current therapeutic strategies focus on chemical treatments targeting neurohumoral systems like the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and employing combination therapies such as β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and newer agents like Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. However, alkaloids—naturally occurring compounds with nitrogen atoms—are emerging as promising agents in CVD treatment. Alkaloids are found in various natural sources and exhibit cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-arrhythmic properties. This review highlights the mechanisms of action of several key alkaloids in heart failure, arrhythmia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and fibrosis.

- Open Access

- Review

Alkaloids and Their Mechanisms of Action in Cardiovascular Diseases

- Anil Kumar Prajapati *,

- Gaurang Shah

Author Information

Received: 15 Jan 2025 | Revised: 03 Mar 2025 | Accepted: 18 Mar 2025 | Published: 01 Sep 2025

Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

alkaloids | mechanism of action | cardiovascular diseases | heart failure | arrhythmia | hypertension | myocardial infarction | myocardial fibrosis

1.Introduction

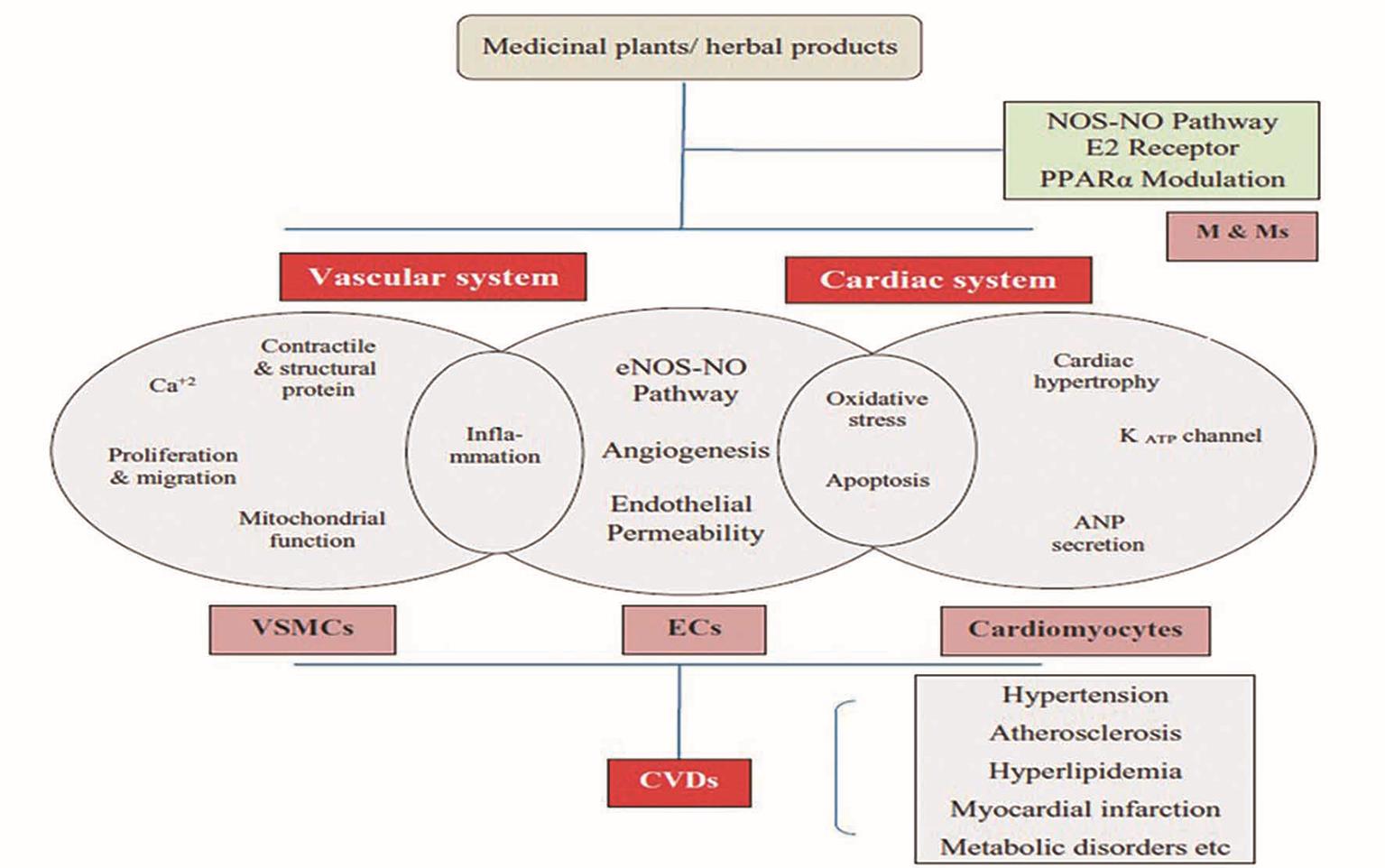

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) refers to a group of conditions that impact the heart and blood vessels. CVD encompasses various conditions, including heart failure, arrhythmia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and myocardial fibrosis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) were responsible for approximately 17.9 million deaths in 2019, accounting for 32% of all global fatalities [1]. Projections between 2025 and 2050 indicate a 90% rise in CVD prevalence. By 2050, cardiovascular-related deaths are expected to reach 35.6 million, up from 20.5 million in 2025 [2]. The development of CVD typically begins with impaired endothelial function, leading to vessel wall inflammation and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, which can result in heart attacks or strokes [3]. Heart failure (HF) involves complex physiological and pathological mechanisms, with various neurohumoral systems playing a crucial role, including the natriuretic peptide system, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), and the central nervous system (CNS) [4]. Additionally, inflammatory mediators, endothelin, and other humoral factors contribute to the disease’s progression. Traditionally, CVD treatment has focused on chemical drugs, evolving from the classic ‘cardiotonic, diuretic, vasodilator’ approach to a cornerstone combination therapy. This “golden triangle” consists of aldosterone receptor antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), and β-blockers. More recently, the introduction of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) has been shown to significantly lower the risk of cardiovascular death or readmission due to heart failure [5].

Alkaloids are a large class of naturally occurring organic compounds that contain one or more nitrogen atoms, often amino or amido groups. These compounds are found in bacteria, fungi, animals, and plants, exhibiting complex and diverse structures. Nitrogen atoms give alkaloids their basic (alkaline) properties, allowing them to react with acids to form salts, similar to inorganic bases. As basic compounds, alkaloids are typically named with the suffix “-ine” and are chemically similar to amines. In their pure form, alkaloids are generally colorless, odorless crystalline solids, though they can sometimes appear as yellowish liquids and often have a bitter taste [6]. Alkaloids play a critical role in both human medicine and the natural defense mechanisms of organisms. Medicinally, they are well-known for their cardioprotective, anesthetic, and anti-inflammatory effects. Commonly used alkaloids in clinical practice include morphine, strychnine, quinine, ephedrine, and nicotine. As of 25 October 2020, the Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) listed 27,683 alkaloids, with 990 newly discovered or reinvestigated between 2014 and 2020 [7]. Alkaloids can be synthesized through several biosynthetic pathways, such as the shikimate, ornithine, lysine, nicotinic acid, histidine, purine, terpenoid, and polyketide pathways [8]. The literature search was conducted using a search engine such as Google Scholar, utilizing keywords such as “Alkaloids”, “Mechanism of Action”, and “cardiovascular diseases”.

2.Mechanism of Action of Alkaloids in CVD

2.1.Alkaloid in Heart Failure

A. Oxymatrine: It is a widely recognized quinolizidine alkaloid extracted from the root of Sophora flavescens Ait [10]. In isoproterenol (ISO)-induced heart failure, there is an increase in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [11]. TLR4, one of the most extensively studied proteins in heart injury, plays a critical role as a mediator of cardiac inflammation and contributes significantly to the progression of cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, TLR4 can activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which promotes the production of inflammatory cytokines and intensifies the inflammatory response. Activation of the MAPK pathway can also trigger nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, leading to its nuclear translocation and the mediation of inflammation. Oxymatrine (OMT), a quinoline alkaloid, exhibits various biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant, anticancer, antifibrotic, and cardiovascular protective effects. OMT was found to significantly reduce ISO-induced cardiac damage, myocardial necrosis, interstitial edema, and fibrosis. Moreover, OMT lowered the levels of Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and inhibited the expression of proteins related to the TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [12]. The structure of Oxymatrine is shown in Figure 2.

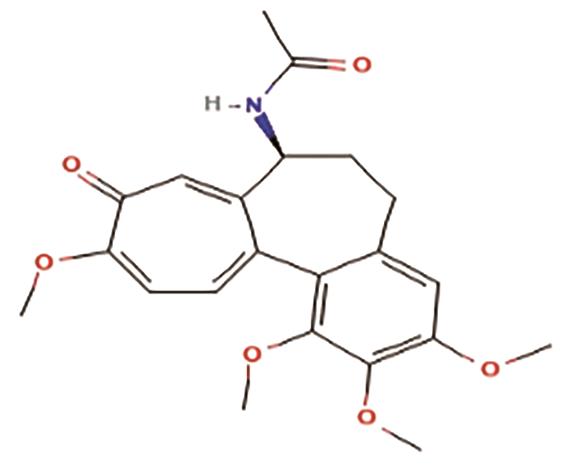

B. Colchicine: It is the main alkaloid of the Colchicum autumnale. It is also an FDA-approved alkaloid for Myocardial Infarction (Table 1). The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome initiates myocardial inflammation, oxidative stress, and coronary endothelial dysfunction, which contribute to cardiomyocyte stiffness, hypertrophy, and myocardial fibrosis—mechanisms believed to be central in developing Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Consequently, molecules capable of inhibiting HFpEF-associated cardiac inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis could offer significant therapeutic advantages. Colchicine has been shown to play a vital role in reducing systemic inflammation and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation, while also mitigating cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis in a high-salt diet (HSD)-induced HFpEF model [13]. The structure of colchicine is shown in Figure 3.

FDA Approved Alkaloids.

| Sr. No. | Alkaloids | FDA Approved Use |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Atropine | Bradycardia |

| 2. | Colchicine | Lower the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, and cardiovascular-related death in adults with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. |

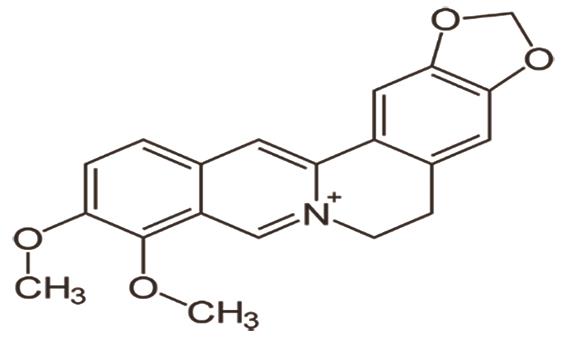

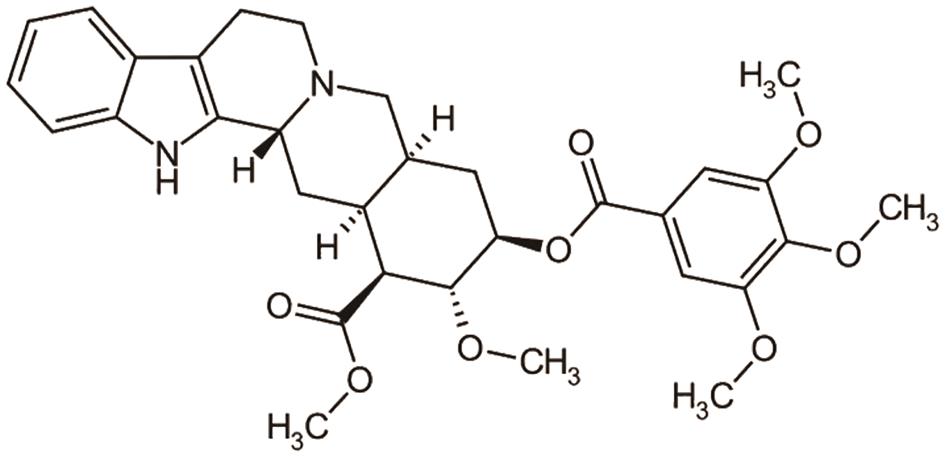

C. Berberine, a plant-derived alkaloid found in many Berberis species, but mainly found in Berberis vulgaris [14]. Heart failure outcomes are indirectly affected by lowering blood pressure through adrenergic receptor blockade and inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which produces a central sympatholytic effect. Its direct effects in heart failure are achieved through various mechanisms, including enhancing coronary artery flow, improving myocardial ischemia caused by pituitrin, regulating heart rate, reducing the incidence of ischemic ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and modulating inward and outward K+ rectifier currents. These actions prolong the duration of the action potential and facilitate rapid repolarization [15]. The structure of berberine is shown in Figure 4.

2.2.Alkaloid in Arrhythmia

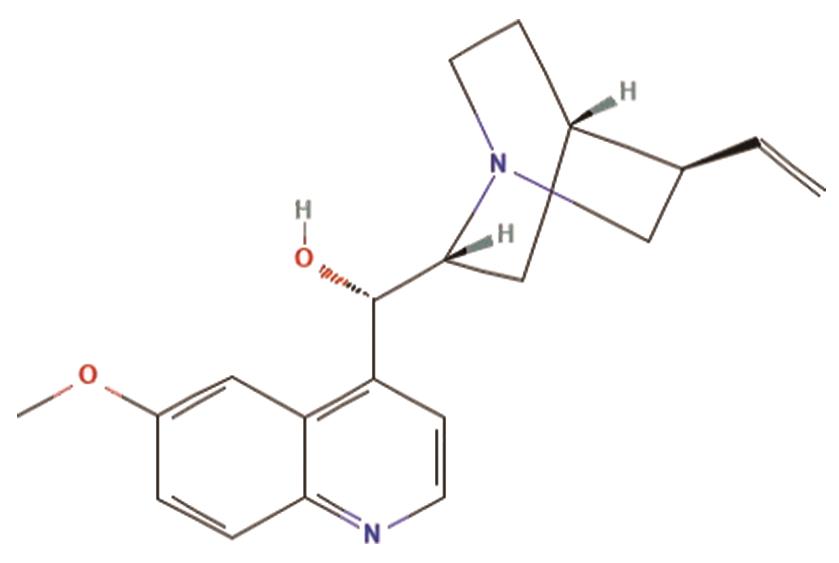

A. Quinidine is the d-isomer of quinine, the primary alkaloid found in the bark of cinchona trees. While quinine is commonly used to treat malaria, quinidine serves as a class Ia antiarrhythmic drug, according to the Vaughan Williams classification. It targets voltage-gated sodium channels (NaV channels) and delayed rectifier potassium channels, playing a key role in managing cardiac arrhythmias [16]. The structure of quinidine is shown in Figure 5.

B. Aloperine, a quinolizidine alkaloid derived from plant Sophora alopecuroides L., functions as an antiarrhythmic agent by inhibiting voltage-gated Na+ channels in rat ventricular myocytes [17]. The structure of aloperine is shown in Figure 6.

C. Acrophyllidine, a furoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Acronychia halophylla, functions as an antiarrhythmic agent by blocking Na+, the transient outward (Ito), and the steady-state outward K+ current (ISS) channels, while partially inhibiting Ca2+ channels, thereby modifying electrophysiological properties [18].

2.3.Alkaloid in Hypertension

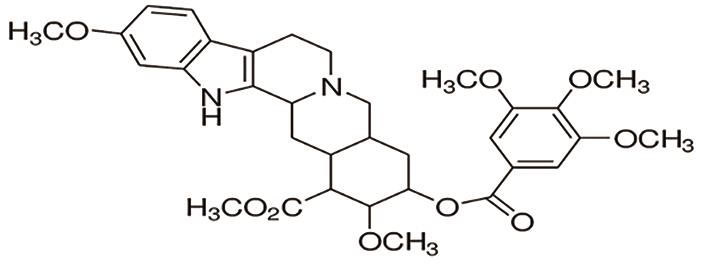

A. Reserpine, the main alkaloid in Rauvolfia serpentina, is known for its antihypertensive properties. It works by inhibiting sympathetic nervous system activity and regulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), effectively reducing blood pressure [19]. The structure of reserpine is shown in Figure 7.

B. Deserpidine is an ester alkaloid present in Rauvolfia serpentina, but it differs from reserpine by the absence of a methoxy group at C-11, which is present in reserpine. Like reserpine, Deserpidine binds to and inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), competing with angiotensin I for binding. This inhibition prevents the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II [20]. The structure of Deserpidine is shown in Figure 8.

2.4.Alkaloid in Myocardial Infarction

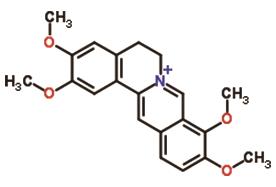

A. Palmatine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid found in Berberis cretica, helps mitigate acute myocardial infarction by activating the pAMPK/Nrf2 signaling pathway [21]. The structure of palmatine is shown in Figure 9.

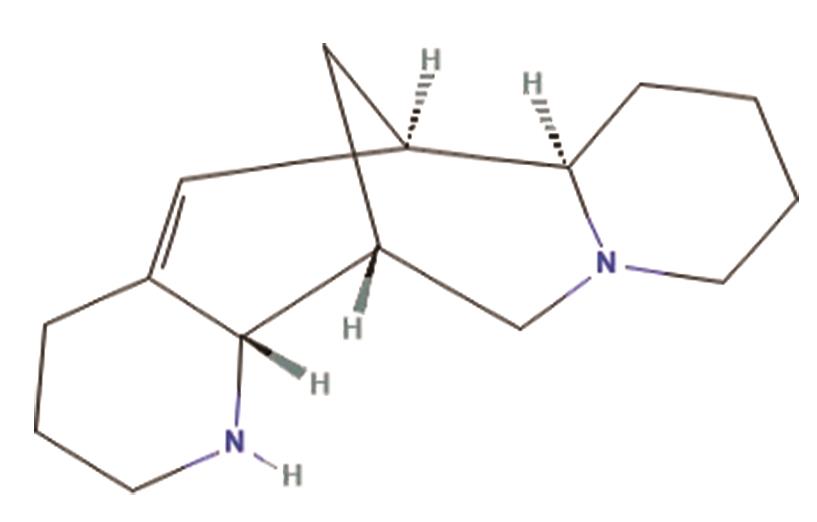

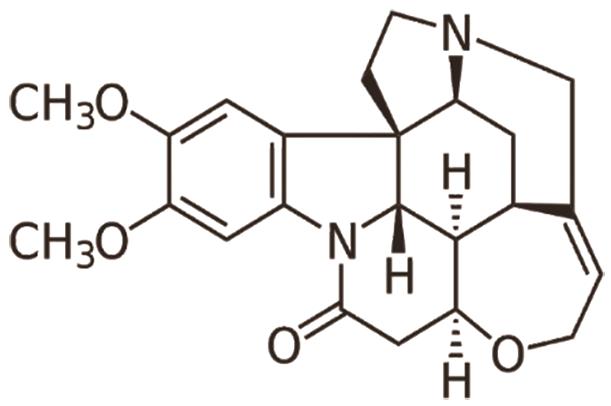

B. Brucine, an alkaloid found in Strychnos nux-vomica, has shown potential in reducing myocardial ischemia injury by inhibiting Na+/K+-ATPase, as demonstrated in a study on isoprenaline-induced myocardial ischemia [22]. The structure of brucine is shown in Figure 10.

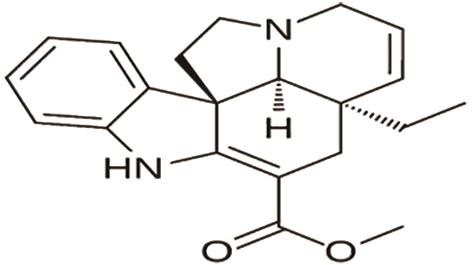

C. Tabersonine, an alkaloid found in Catharanthus roseus, effectively treats myocardial infarction by reducing cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. It achieves this by targeting transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and inhibiting TAK1-mediated inflammation [23]. The structure of tabersonine is shown in Figure 11.

2.5.Alkaloids for Myocardial Fibrosis

A. Palmatine, a protoberberine alkaloid found in Berberis cretica, helps reduce myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting fibroblast activation via the STAT3 pathway and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and interleukin-6 [24].

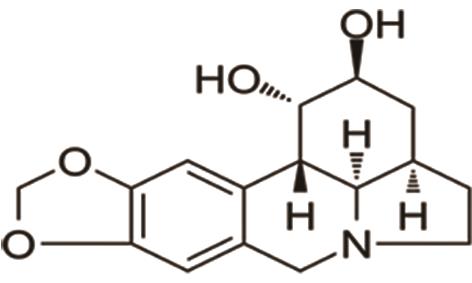

B. Dihydrolycorine: It is found in Lycoris radiata. In pathological conditions like acute myocardial infarction (MI), increased Runx1 expression reduces cardiac contractile function. Dihydrolycorine, an alkaloid, has shown promise as a Runx1 inhibitor. Treatment with this compound may help prevent adverse cardiac remodeling by downregulating fibrotic genes, such as collagen I, TGFβ, and p-smad3, and reducing the expression of the apoptosis gene Bax. Additionally, it improves cardiac function indicators, including Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), Left ventricular systolic function (LVSF), Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) [25]. The structure of dihydrolycorine is shown in Figure 12.

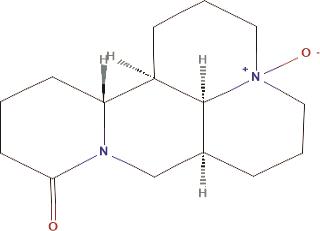

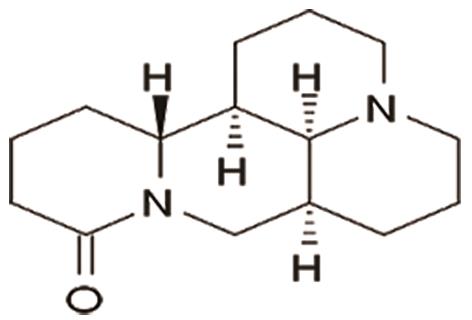

C. Matrine: It is a quinolizidine alkaloid derived from Radix sophorae flava and reduces pathological cardiac fibrosis by modulating the RPS5/p38 signaling pathway [26]. The structure of matrine is shown in Figure 13.

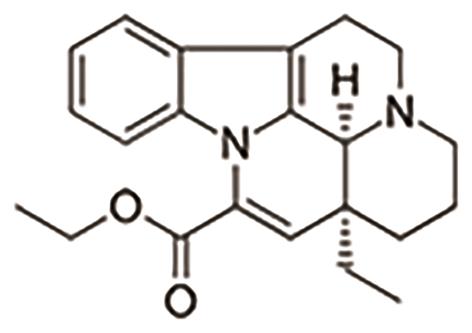

D. Vinpocetine is derived from a slight modification of vincamine, an alkaloid extracted from the periwinkle plant (Vinca minor). It helps prevent pathological cardiac remodeling, such as myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, by targeting Phosphodiesterase 1 (PDE1) [27]. The structure of vinpocetine is shown in Figure 14.

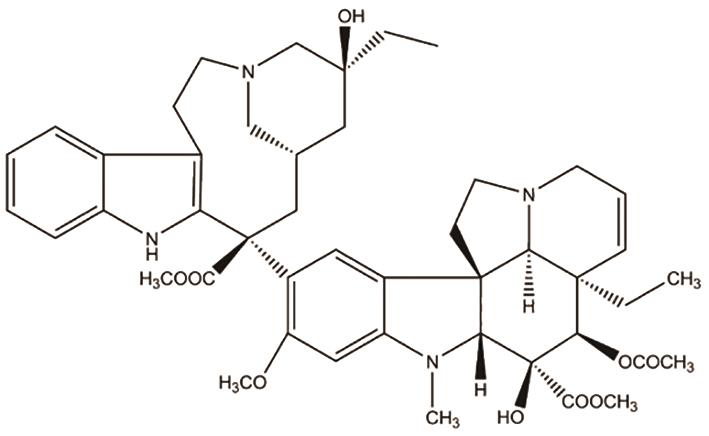

E. Vincristine reduces cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [28]. The structure of vincristine is shown in Figure 15.

3.Limitation

Alkaloids used in cardiovascular disease management face several limitations, including bioavailability, standardization, safety, and clinical efficacy. Therefore, further research is required to evaluate their effectiveness and safety across different populations and to establish the optimal dosage and formulation.

4.Challenges in Alkaloid-Based Cardiovascular Therapy

Alkaloids have significant therapeutic promise in the treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but several obstacles prevent their widespread use and practical translation. These difficulties mostly consist of regulatory obstacles, pharmacokinetic restrictions, toxicity issues, and difficulties with isolation and synthesis. The difficulty of isolating and synthesizing alkaloids is one of the main obstacles to using them for CVD treatment. Because alkaloids are frequently found in extremely small amounts in their natural sources, large-scale extraction is expensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, their complex chemical structures make synthetic manufacturing extremely challenging, necessitating sophisticated methods and specialized knowledge to accomplish effective and scalable synthesis. These elements support the exorbitant price and restricted accessibility of treatments based on alkaloids. The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of alkaloids is another important concern. Numerous alkaloids have limited systemic bioavailability, fast metabolism, and poor water solubility, all of which considerably diminish their therapeutic efficacy in vivo. To overcome these constraints and guarantee long-lasting therapeutic benefits, sophisticated drug delivery techniques such as liposomal formulations, nanoencapsulation, and prodrug methods must be developed. However, before being used in therapeutic settings, these tactics need more investigation and regulatory clearance. Alkaloid treatment also raises serious questions about toxicity and adverse consequences. Even though many alkaloids have strong pharmacological properties, other substances, like strychnine and aconitine, are extremely poisonous at therapeutic dosages. To guarantee safety throughout medication development, this calls for exacting dose optimisation, risk assessment, and toxicity profiling. To address these issues and provide a beneficial therapeutic index, comprehensive preclinical and clinical research is needed. The development of medications based on alkaloids is further hampered by supply and regulatory limitations. Because of the strict standards for efficacy, safety, and quality control, the regulatory approval procedure for therapies derived from natural products is frequently drawn out. Furthermore, considering the various environmental, agricultural, and geopolitical factors that can impact production, it is still difficult to guarantee a steady and continuous supply of alkaloid-rich plant sources.

5.Future Direction

Computational Tool Integration: The field of alkaloid-based drug discovery is changing as a result of developments in computational biology and artificial intelligence (AI). The effectiveness of drug development can be increased by using AI-driven algorithms to anticipate binding affinities, optimize lead compounds, and speed up structure-activity relationship (SAR) research. The time and expense involved in finding effective and specific alkaloid-based treatments for cardiovascular disorders can be greatly decreased by using these computational techniques.

Green Chemistry Innovations: To increase sustainability in medication development, alkaloid research is increasingly adopting green chemistry concepts. Eco-friendly extraction methods, biodegradable catalysts, and renewable solvents are being investigated as ways to improve the sustainability of alkaloid synthesis and separation. These developments address both ecological and economic issues by lowering the environmental impact while also facilitating scalable and affordable production.

6.Conclusions

Alkaloids, a diverse class of naturally occurring compounds, exhibit significant cardioprotective effects in various cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, arrhythmia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and myocardial fibrosis. Their mechanisms of action involve anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-arrhythmic, and vasodilatory properties, often targeting key signaling pathways such as TLR4/NF-κB, MAPK, RAAS, and PDE1. Notable alkaloids like oxymatrine, colchicine, berberine, and quinidine have demonstrated therapeutic potential in both preclinical and clinical studies. While traditional CVD treatments rely on neurohumoral modulation, alkaloids offer promising complementary or alternative approaches. Further research is needed to optimize their efficacy, safety, and clinical applications in cardiovascular medicine.

Author Contributions: A.K.P. wrote and edited the manuscript, and G.S. supervised the review article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments: Piyush Parmar.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

|

Cardiovascular diseases |

(CVDs) |

|

|

Heart failure |

(HF) |

|

|

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

(RAAS) |

|

|

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

(ACEIs) |

|

|

Angiotensin II receptor blockers |

(ARBs) |

|

|

Dictionary of Natural Products |

(DNP) |

|

|

Isoproterenol |

(ISO) |

|

|

Oxymatrine |

(OMT) |

|

|

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

(HFpEF) |

|

|

High-salt diet |

(HSD) |

|

|

Acetylcholinesterase |

(AChE) |

|

|

Myocardial infarction |

(MI) |

|

|

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

(LVEF) |

|

|

Left ventricular end-systolic dimension |

(LVESD) |

|

|

Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension |

(LVEDD) |

|

|

Left ventricular systolic function |

(LVSF) |

References

- 1.

Jan, B; Dar, M.I; Choudhary, B; et al. cardiovascular diseases among Indian Older Adults: A Comprehensive Review. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2024, 2024, 6894693.

- 2.

Chong, B; Jayabaskaran, J; Jauhari, S.M; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, zwae281. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae281.

- 3.

Wargocka-Matuszewska, W; Uhrynowski, W; Rozwadowska, N; et al. Recent Advances in Cardiovascular Diseases Research Using Animal Models and PET Radioisotope Tracers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 353.

- 4.

Prajapati, AK; Shah, G; Exploring in vivo and in vitro models for heart failure with biomarker insights: a review. The Egypt Heart J. 2024; 76:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-024-00568-1

- 5.

Chen, X.-J; Liu, S.-Y; Li, S.-M; et al. The recent advance and prospect of natural source compounds for the treatment of heart failure. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27110.

- 6.

Kurek, J. Introductory Chapter: Alkaloids-Their Importance in Nature and for Human Life; Alkaloids–Their Importance in Nature and Human Life; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019.

- 7.

Heinrich, M; Mah, J; Amirkia, V; Alkaloids Used as Medicines: Structural Phytochemistry Meets Biodiversity—An Update and Forward Look. Molecules 2021, 26, 1836.

- 8.

Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P; López-Martínez, L.X; Contreras-Angulo, L.A; et al. Plant Alkaloids: Structures and Bioactive Properties; Plant-Derived Bioactives; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 85–117.

- 9.

Shah, S.M.A; Akram, M; Riaz, M; et al. Cardioprotective Potential of Plant-Derived Molecules: A Scientific and Medicinal Approach. Dose Response 2019, 17, 155932581985224.

- 10.

Runtao, G; Guo, D; Jiangbo, Y; et al. Oxymatrine, the Main Alkaloid Component of Sophora Roots, Protects Heart against Arrhythmias in Rats. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 226–230.

- 11.

Katare, P.B; Bagul, P.K; Dinda, A.K; et al. Toll-Like Receptor 4 Inhibition Improves Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Health in Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Rats. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 719.

- 12.

Sun, H; Bai, J; Sun, Y; et al. Oxymatrine attenuated isoproterenol-induced heart failure via the TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK pathways in vivo and in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 941, 175500.

- 13.

Shen, S; Duan, J; Hu, J; et al. Colchicine alleviates inflammation and improves diastolic dysfunction in heart failure rats with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 929, 175126.

- 14.

Neag, M.A; Mocan, A; Echeverría, J; et al. Berberine: Botanical Occurrence, UsesTraditional, MethodsExtraction, and Relevance in Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Hepatic, and DisordersRenal. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 557.

- 15.

Carrizzo, A; Izzo, C; Forte, M; et al. A Novel Promising Frontier for Human Health: The Beneficial Effects of Nutraceuticals in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8706.

- 16.

Quinidine, D.J; . Encyclopedia of Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 593–594.

- 17.

Li, M; Du, Y; Zhong, F; et al. Inhibitory effects of aloperine on voltage-gated Na+ channels in rat ventricular myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2021, 394, 1579–1588.

- 18.

Chang, G.-J; Wu, M.-H; Chen, W.-P; et al. Electrophysiological characteristics of antiarrhythmic potential of acrophyllidine, a furoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Acronychia halophylla. Drug Dev. Res. 2000, 50, 170–185.

- 19.

Shankar. T, Srinivas. T. Studies on Biological Activity and Mechanisms of Action in Alkaloids of Rauvolia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex-Kurz. for Hypertension Lowering. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 12, 1623–1625.

- 20.

Varchi, G; Battaglia, A; Samorì, C; et al. Synthesis of Deserpidine from Reserpine. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1629–1631.

- 21.

Hao, M; Jiao, K; Palmatine Alleviates Acute Myocardial Infarction Through Activating pAMPK/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Mouse Model. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2022, 32, 627–635.

- 22.

Liu, B; Zhang, Y; Wu, Q; Wang, L; Hu, B; Alleviation of isoprenaline hydrochloride induced myocardial ischemia injury by brucine through the inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 149, 111332.

- 23.

Dai, C; Luo, W; Chen, Y; et al. Tabersonine attenuates Angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling and dysfunction through targeting TAK1 and inhibiting TAK1-mediated cardiac inflammation. Phytomedicine 2022, 103, 154238.

- 24.

Lin, S; Zhang, S; Zhan, A; et al. Palmatine alleviates cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting fibroblast activation through the STAT3 pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 967, 176395.

- 25.

Ni, T; Huang, X; Pan, S; et al. Dihydrolycorine Attenuates Cardiac Fibrosis and Dysfunction by Downregulating Runx1 following Myocardial Infarction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8528239.

- 26.

Zhang, X; Hu, C; Zhang, N; et al. Matrine attenuates pathological cardiac fibrosis via RPS5/p38 in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 573–584.

- 27.

Wu, M; Zhang, Y; Xu, X; et al. Vinpocetine Attenuates Pathological Cardiac Remodeling by Inhibiting Cardiac Hypertrophy and Fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 157–166.

- 28.

Ge, C; Cheng, Y; Fan, Y; et al. Vincristine attenuates cardiac fibrosis through the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 1409–1426.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.