Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) is a complex clinical and pathological condition characterized by the dysfunction of either the heart or the kidney, leading to subsequent dysfunction in the other organ in the context of acute or chronic functional impairment. Given the escalating incidence and mortality rates of CRS particularly against the backdrop of an aging population and the rising prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, underscore the need for a deeper understanding of its underlying pathogenesis. Recently, the role of mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in CRS has garnered significant research attention. Evidence suggests that aberrant activation of MR not only disrupts water and sodium homeostasis, resulting in abnormal blood volume expansion, but also triggers inflammatory responses, tissue fibrosis, and hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. These intricate pathophysiological processes exert profound negative impacts on cardiac and renal functions. Finerenone, a novel non-steroidal selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), has demonstrated significant therapeutic potential and unique pharmacological mechanism in the treatment of cardiorenal syndrome, especially chronic kidney disease (CKD) associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in recent years. In this review, we summarize the mechanisms by which finerenone interacts with MR and its promising therapeutic role in cardiorenal syndrome.

- Open Access

- Review

Finerenone Targeting the Mineralocorticoid Receptor: Therapeutic Potential for Cardiorenal Syndrome

- Hairui Zhao 1,

- Chunyv Pan 2,

- Xiaojing Cai 2,

- Manyi Wu 2,

- Bowen Qin 1,

- Hui Zhang 1,

- Hengzhi Du 2,*,

- Junhua Li 1,2,*

Author Information

Received: 07 Oct 2024 | Revised: 17 Dec 2024 | Accepted: 18 Dec 2024 | Published: 03 Nov 2025

Abstract

1.Introduction

Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) is defined as a pathophysiological disease that involves both the heart and the kidneys. It is characterized by the acute or chronic dysfunction of one organ, which primarily leads to dysfunction in the other organ and secondarily affects its function [1,2]. CRS establishes a vicious cycle wherein cardiac and renal dysfunction mutually exacerbate each other, thereby establishing a highly intricate and multifaceted network of biological communication and feedback mechanisms. These mechanisms encompass cellular, molecular, neural, endocrine, and paracrine processes [3]. Furthermore, CRS exerts a profound impact on quality of life and introduces considerable variability in prognosis, thereby attracting significant attention due to its intimate association with elevated mortality rates [4]. Consequently, a thorough investigation of the pathogenesis of CRS and the pursuit of effective treatment strategies possesses significant clinical value and profound implications.

Mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) is an important transcription factor that regulates various physiological processes by binding to mineral corticoids to maintain cardiovascular and renal homeostasis [5, 6]. As a nuclear receptor, MR regulates the biological activity of mineralocorticoids, thereby participating in the modulation of various physiological processes including which is essential for ensuring water-electrolyte balance, blood pressure stability, and cardiovascular health [7,8]. However, studies have shown that MR is abnormally activated in CRS patients, promoting excessive inflammation, fibrosis, oxidative stress, and apoptosis, which exacerbate heart and kidney damage [9]. Therefore, regulating the activity and expression level of MR is regarded as a potential new strategy for the treatment of CRS [10].

Finerenone, as a third generation non-steroidal selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects and improves cardiac and renal function by blocking the overactivation of MR [11]. Currently, finerenone is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes-related CKD [12]. With the accumulation of clinical evidence, the application of finerenone in patients with heart failure and the combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors are also being explored [13,14]. These studies are expected to further expand the application of finerenone in the treatment of CRS. In this review, we summarized the mechanistic of finerenone in CRS by interacting with MR and its promising therapeutic role in CRS.

2.Overview of CRS

2.1.Classifications and Epidemiological Characteristics of CRS

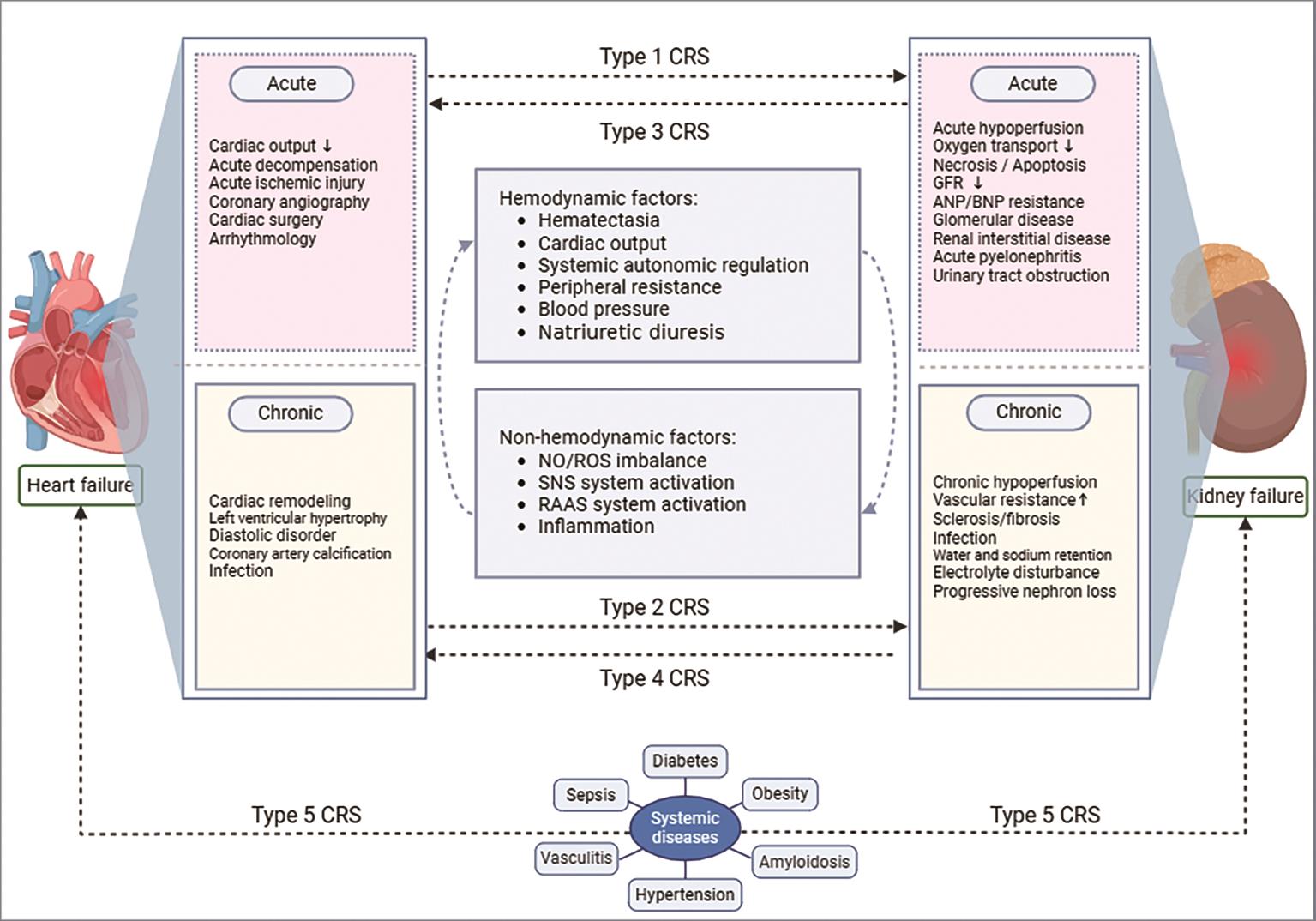

According to the CRS consensus document published by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) in 2008 [15]. CRS is systematically classified into five subtypes, characterized by the sequential involvement of organs and the nature of disease progression [16]. Type 1 CRS encapsulates a significant decline in cardiac function, such as acute cardiogenic shock or decompensated congestive heart failure, which subsequently induces acute kidney injury (AKI) [17]. Type 2 CRS is marked by chronic abnormalities in cardiac function, exemplified by chronic congestive heart failure, leading to the progressive exacerbation of CKD [18]. Type 3 CRS refers to the sudden deterioration of renal function, such as acute renal ischemia or glomerulonephritis, which triggers acute cardiac dysfunction encompassing heart failure, arrhythmias, and ischemia [19,20]. Type 4 CRS describes a scenario in which CKD, such as chronic glomerular disease, results in diminished cardiac function, cardiac hypertrophy, and elevated risk of adverse cardiovascular events [21]. Type 5 CRS encompasses systemic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, sepsis, that result in concurrent cardiac and renal dysfunction [22].

In developing countries, the burden of CRS is particularly severe due to the scarcity of resources for screening and treatment. Consequently, there is an urgent necessity to enhance and optimize public health and medical services in these regions [23,24]. CRS is particularly prevalent among hospitalized patients, especially those with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), and approximately 25% progress to type 1 CRS [25]. AKI occurs in up to 50% of cardiac intensive care units. Type 2 CRS is common in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) and has a 45% reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [26,27]. In type 3 CRS, the incidence of AKI is 9% among hospitalized patients and 35% among intensive care patients. Specific incidence data are insufficient [19,28]. Type 4 CRS poses a significant challenge to public health, as half of all patients with ESRD succumb to coronary heart disease (CHD) and its associated complications [21,29]. Type 5 CRS is more common in severe patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [22,30]. Given global aging and lifestyle changes, the incidence of CRS is expected to increase [31].

2.2.Pathogenesis of CRS

With the deepening of research, the pathogenesis of CRS is gradually explored ( Figure 1) [31,32]. As a vital organ responsible for maintaining homeostasis, the kidney adapts to variations in blood flow by adjusting the functions of renal tubule reabsorption and excretion [33]. When the heart function is compromised, specifically including ADHF, ischemic injury, coronary angiography, and cardiac surgery, which in turn may give rise to AKI. Notably, the mechanisms through which these events mediate AKI may differ [34–36]. Additionally, the deregulated neuroendocrine and cytokine systems play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of CRS [37]. Cardiac insufficiency initiates a robust activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [38,39]. This cascading effect not only results in vasoconstriction and a significant decrease in renal blood flow but also fosters the retention of water and salt, thereby exacerbating the circulatory and renal burden [40]. Specifically, the elevated aldosterone levels not only enhance the capacity of kidney for sodium reabsorption but also accelerate tubular fibrosis, ultimately causing persistent and substantial renal dysfunction [41].

Furthermore, inflammation, which serves as a crucial factor in the etiology of CRS, persists throughout the entire course of the occurrence and development of the CRS [31,42]. The initial injury of the heart and kidney triggers a wide range of inflammatory responses, leading to the release of numerous inflammatory cytokines. These mediators facilitate the infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells [27,37]. Furthermore, the persistent inflammatory state may stimulate the remodeling of the heart and promote fibrotic processes in the kidney, thereby exacerbating their respective functions and perpetuating a vicious cycle that ultimately contributes directly to damage and dysfunction of both the heart and kidney [43].

Thus, a meticulous investigation into the intricate interplay of mechanisms underlying CRS pathogenesis offers a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the disease, and provides a solid theoretical basis and practical guidance for the development of more precise and effective treatment strategies [44,45]. Ongoing and future research endeavors should prioritize the discovery of novel molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways, ultimately improving patient outcomes and prognosis [1].

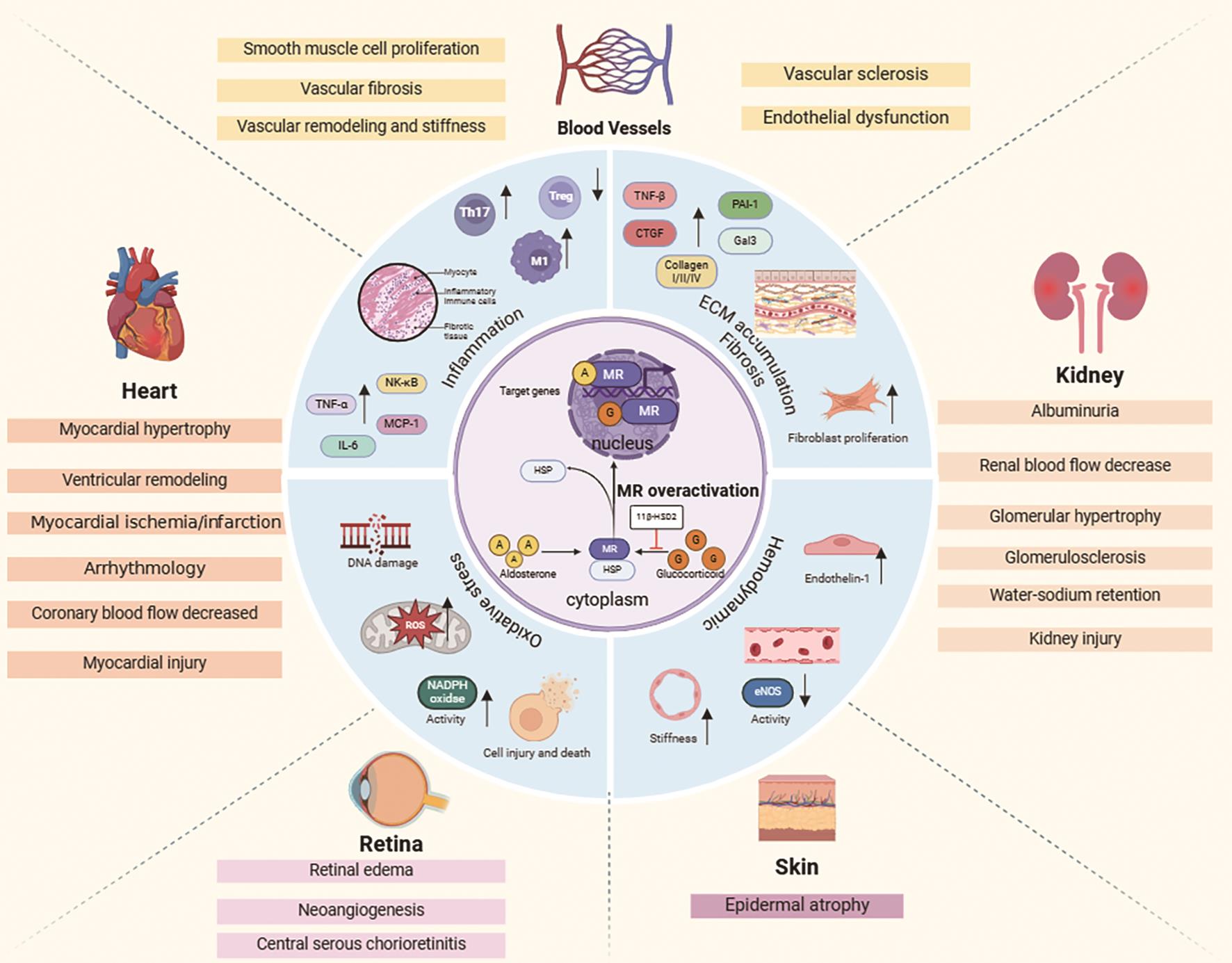

3.Biological Characteristics of MR

MR, a nuclear hormone receptor, functions as a ligand-activated transcription factor with three key components: amino-terminal transcription activation domain (AF-1), the DNA binding domain (DBD), and the carboxyl-terminal ligand binding domain (LBD) [46,47]. In the absence of ligands, MR remains inactive in the cytoplasm with heat shock protein (HSP). Binding of ligands triggers conformational changes, leading to HSP dissociation, DBD exposure, and nuclear translocation of MR [48,49]. Within the nucleus, MR uses its DBD to interact with hormone response elements on target genes, orchestrating their transcriptional activation or inhibition [50]. MR has similar affinity for progesterone, cortisol, aldosterone, and other endogenous steroids [51]. Key functional groups at C17 and C11 in its structure are crucial for ligand binding and maintaining MR activity. The C17 hydroxyl group is essential for MR-ligand binding. Additionally, the structure of MR includes modifiable sites like phosphorylation and acetylation sites [52], which significantly impact its stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity [53,54]. Physiologically, MR is widely distributed in key tissues like kidneys, heart, and blood vessels, performing numerous functions ( Figure 2). In the kidney, it regulates sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion, maintaining fluid balance and blood pressure. In blood vessels, MR modulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and contraction [55–57]. Therefore, there is great potential for specific treatment of MR in CRS.

4.Roles of MR in CRS

The signaling pathway of MR not only governs fundamental physiological processes but also plays a pivotal role in the occurrence and progression of CRS [58–60]. In the cytoplasm, the initial interaction between aldosterone and MR initiates a cascade of events that ultimately determines cellular behavior [61]. Aldosterone, a potent mineralocorticoid, circulates through the bloodstream like a messenger, delivering its signal to specific receptors on the surface or within target cells, primarily renal tubular epithelial cells [62]. Aldosterone binding to MR triggers a notable conformational change, exemplifying the molecular machinery in action. This transformation facilitates the translocation of MR from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and prepares it for interaction with DNA [63,64]. In the nucleus, MR acts as a master regulator, selectively binding to hormone response elements, modulating the expression of target genes, interacting with transcription factors, co-activators, and co-repressors, forming a vast network of molecular interactions [65,66]. In conclusion, the signal transduction mechanism of MR is a highly sophisticated and multifaceted process that involves hormone binding, receptor activation and translocation, gene transcription regulation, and crosstalk with multiple signaling pathways [67,68].

Through the decoding of the intricate mysteries surrounding above mechanism, a profound understanding of the underlying causes of numerous diseases is gained, enabling the development of highly efficacious therapeutic methodologies to address and combat them [69]. For example, in the distal nephrons, aldosterone binding to MR enhances the transcription and activity of the epithelial sodium channel, increasing sodium and fluid reabsorption, thereby maintaining fluid balance, and promoting potassium excretion to regulate electrolyte balance further [70–72]. In renal epithelial cells, the specific enzymatic activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 converts cortisol to cortisone, which in turn does not bind to MR, thereby establishing aldosterone as the primary functional ligand for MR [73–75]. Recent studies have demonstrated that excessive activation of the MR plays a pivotal role in various pathological processes within the kidney, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis. These processes, in turn, may facilitate the onset and progression of CRS [76,77]. In diabetic patients, hyperglycemia triggers the activation of the RAAS system, leading to an elevation in plasma aldosterone levels. Ultimately, this results in the excessive activation of MR and exacerbates renal fibrosis [78]. Furthermore, the inhibition of MR activity has been shown to effectively mitigate inflammation and fibrosis in the kidney, ultimately delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy [79]. Many studies suggested that MR are also overactivation in patients with hypertension, resulting in sodium and fluid retention and exacerbating renal damage and MR inhibitor could significantly reduce blood pressure and improve renal function in patients with hypertension [80,81].

The activation of MR is also implicated in renal oxidative stress and inflammation processes associated with CRS. Notably, MR antagonists have been shown to significantly delay the progression of CRS [82]. For example, Jonatan et al. evaluated the antagonistic effect of MR or the deletion of MR genes in SMCs in Large White pigs, limiting IR-induced renal injury by influencing Rac1-mediated MR signaling, indicating that MR may play a significant role in type 1 CRS or type 3 CRS [83]. Chang et al. conducted a 6-month long-term observation using the rat UUO model to induce chronic renal and cardiac injuries, thereby simulating the type 4 CRS model, and demonstrated that early treatment with the MR antagonist eplerenone can significantly alleviate MR activation and cardiac fibrosis through the MR-IL-1β-VEGFA signaling pathway [84]. Moreover, in addition, many studies have shown that knock-out MR Studies can delay renal and cardiac disease progression, and may have a positive impact on the treatment and prognosis of various CRS subtypes [85,86].

In addition to the role in kidney, MR is also involved in regulating cardiac function [9,87]. Under physiological conditions, MR plays a crucial role in modulating the excitability and conduction of cardiomyocytes, thereby maintaining the normal rhythm of cardiac electrical activity and preventing abnormal electrical phenomena such as arrhythmias [88]. Under pathological conditions, over-activation of MR is also involved in the occurrence and development of heart disease. For example, Daniela et al. suggested that inflammatory crosstalk between TIMD4+ macrophages and fibroblasts may involve the macrophage MR and mitochondrial superoxide anion release and they further demonstrated that MR deficiency in macrophages reduces the formation of fibrotic niches in the aging heart, protecting against inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction [89]. Multiple research endeavors have conclusively demonstrated a direct influence of MR on cardiac fibroblasts, fostering remodeling extracellular matrix (ECM). Initial investigations utilizing isolated rat cardiac myofibroblasts revealed that aldosterone stimulates fibroblast proliferation through the activation of the Ki-RasA/MAPK1/2 signaling cascade. Notably, this stimulatory effect was mitigated by the administration of spironolactone [90]. Further corroborating this finding, aldosterone-induced proliferation in rat cardiac fibroblasts was enhanced, as evidenced by the upregulation of cyclin D1 and E2 expression [91]. Consequently, aldosterone-mediated activation of MR contributes to the proliferation of fibroblasts.

In summary, the MR is expressed in various body cells, specifically including heart and kidney cells and governs pathophysiological processes in CRS [92,93]. Therefore, the selection of an efficient and safe mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) is of paramount importance for the prevention and treatment of CRS.

5.Finerenone: The Third-Generation Non-Steroidal Selective Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists

5.1.Properties and Mechanism of Action of Finerenone

Finerenone is a novel oral non-steroidal MRAs, that effectively blocks the excessive activation of MR induced by factors such as elevated aldosterone levels [5,11]. Finerenone possesses potent anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic characteristics, enabling it to efficiently safeguard crucial organs like the heart and kidney, delivering dual therapeutic advantages for patients with conditions impacting these organs [94]. Finerenone is considered a pioneering “first-in-class” medication, ideally suited for adult patients with type 2 diabetes-associated CKD to reduce the risk of sustained eGFR decline, ESRD, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization due to heart failure [95].

Unlike traditional steroidal MRAs, finerenone exhibits distinct physicochemical properties and tissue distribution characteristics, demonstrating higher selectivity and stronger antagonistic potency towards MR (Table 1) [96]. In addition to its favorable effects on both the heart and kidney, finerenone also mitigates the risks associated with hyperkalemia and sex hormone-related adverse reactions, further enhancing its overall safety profile [97,98]. Research indicates that finerenone demonstrates superior safety and tolerability compared to traditional drugs [13,99]. Owing to its short half-life and the absence of active metabolites, finerenone may alleviate common adverse reactions, including electrolyte imbalances (particularly hyperkalemia), and potential deterioration of renal function [100].

Comparison of the Finerenone with traditional steroidal MRAs and the manifestation of its advantages.

| Characteristics | Spironolactone | Eplerenone | Finerenone | Embodiment of Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural properties | Flat (Steroidal) | Flat (Steroidal) | Bulky (Non-steroidal) | Kidney and heart dual benefits, Stronger anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects |

| Tissue distribution | Kidney >> Heart | Kidney > Heart | Kidney = Heart | |

| MR affinity | High (+++) | Low (+) | High (+++) | |

| Half-life (hours) | Long (>20) | Medium (3–6) | Short (2–4) | Lower risk of hyperkalemia |

| Absorption | 100% bioavailable | 69% bioavailable | 44% bioavailable | |

| Metabolites | Active metabolites | No active | No active | |

| MR selectivity | Low (+) | Medium (++) | High (+++) | Lower risk of hormone-related adverse reactions |

| Adverse reaction | Hyperkalemia,Hypolibido,Gynecomastia,Sexual dysfunction | Hyperkalemia,Hyponatremia,Hyperlipidemia | Hyperkalemia, No other major adverse reactions were observed |

5.2.The Antagonistic Effect of Finerenone on MR

With in-depth research into finerenone and its mechanism of action, accumulating evidence indicates that finerenone can effectively influence multiple pivotal steps in the MR signaling pathway, positively impacting cardiovascular and renal health [101]. Studies have shown that finerenone can more effectively alter the nuclear transport and subcellular localization of MR [102,103]. Compared to the traditional MRA spironolactone, finerenone demonstrates superior efficacy in this regard [104]. This regulatory effect may be achieved by influencing the distribution of MR between the nucleus and cytoplasm, thereby enhancing or inhibiting its transcriptional activity on target genes [105].

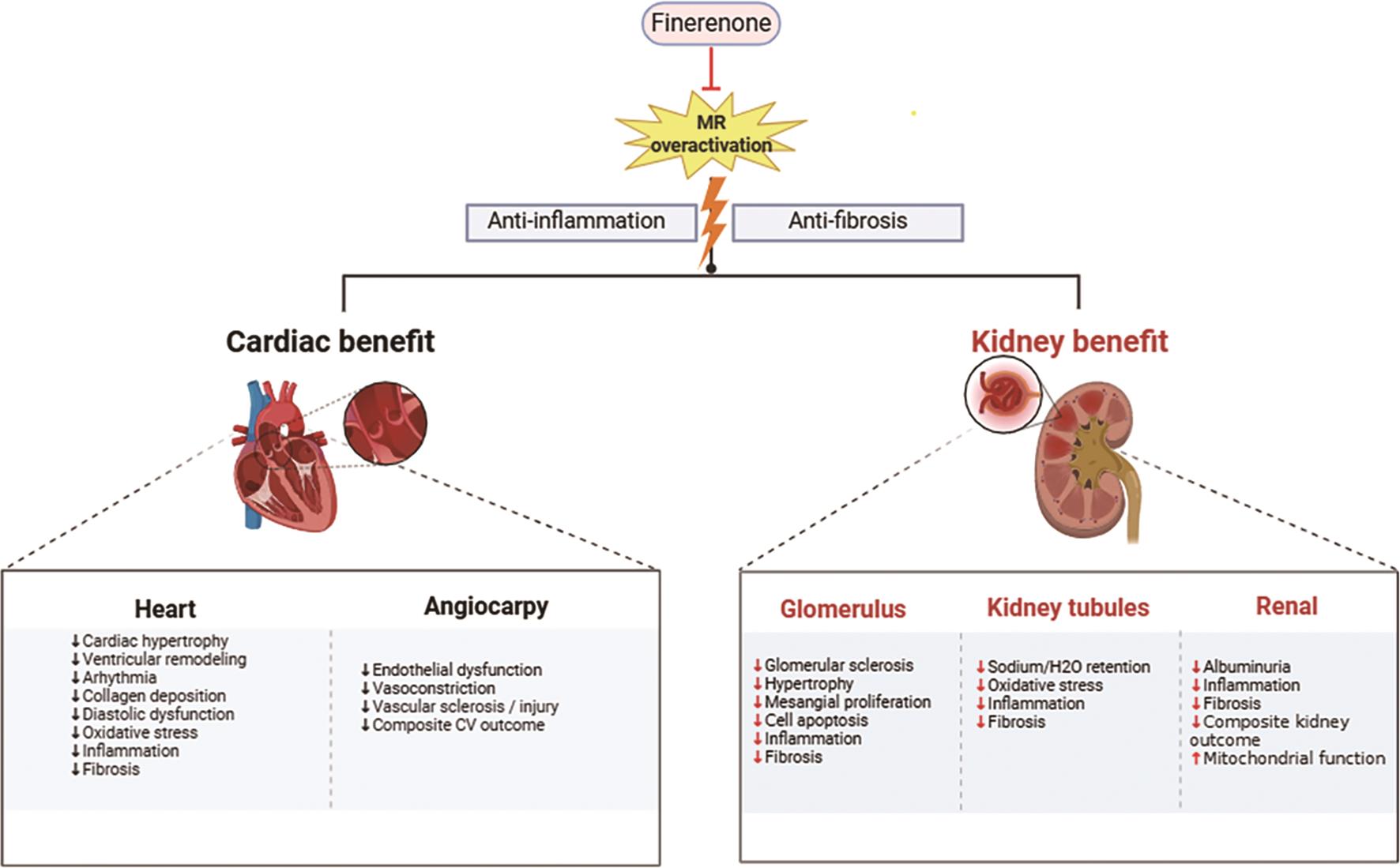

5.3.The Protective Effects of Finerenone on the Heart and Kidney

Finerenone has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in improving renal function (Figure 3) [106]. By precisely inhibiting the excessive activation of aldosterone receptors, it effectively slows down the decline in GFR, thereby safeguarding the fundamental renal functions [107]. Furthermore, finerenone significantly reduces proteinuria levels, a crucial indicator of renal disease progression, suggesting effective containment of renal injury [108,109]. Importantly, finerenone possesses the capability to repair renal cells, offering comprehensive protection to the kidneys by alleviating inflammatory and fibrotic responses, this ultimately reducing the risk of patients progressing to ESRD [110].

Additionally, finerenone plays a pivotal role in cardiac protection [111]. By blocking the excessive activation of MR in the heart and blood vessels, it alleviates cardiac burden and contributes to the enhancement of overall cardiac function [112]. Specifically, finerenone potently inhibits cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, which are key pathological mechanisms underlying heart diseases such as heart failure [113]. Through this mechanism, finerenone safeguards cardiac structure and function while mitigating the risk of cardiovascular events [13]. Moreover, finerenone regulates fluid balance, mitigating the adverse effects of fluid retention on the heart, further consolidating its position in cardiac protection [94,114]. Furthermore, the therapeutic action of finerenone involves the restoration of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway in diabetes. Finerenone treatment can restore the activity of this signaling pathway, which is closely related to the improvement of mitochondrial function [115]. This suggests that MR activation plays a pivotal role in mitochondrial dysfunction associated with diabetic tubular injury [45,116].

Modulating inflammation and fibrosis within cardiac tissue is a complex process that involves the pivotal role of the MR signaling pathway. Research has shown that this pathway significantly contributes to the inflammatory and fibrotic responses in cardiac tissue [117,118]. Finerenone can inhibit inflammatory responses and remodeling processes in cardiac tissue by regulating MR signaling in macrophages [119]. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for treating CRS, as it may help alleviate cardiac damage [120]. Finerenone also modulates the expression of various target genes involved in physiological processes such as electrolyte handling, cardiovascular function, neuronal fate determination, and adipocyte differentiation [121]. In this manner, finerenone not only improves water-sodium balance but also exerts positive effects on cardiovascular and metabolic systems [122].

6.Application of Finerenone in CRS

Finerenone has demonstrated its efficacy in multiple clinical trials [123]. Two landmark Phase 3 trials, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, have shown that compared to placebo, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and extensive CKD, finerenone reduces the risk of cardiovascular and renal failure outcomes, outweighing the risk of hyperkalemia [124,125]. In these two studies, finerenone significantly reduced the risk of kidney disease progression (17.8% vs. 21.1%) and positively affected cardiovascular risk. The FIDELITY study is a pooled analysis of two large Phase III clinical trials, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, which represent the most comprehensive research conducted to date in the field of T2D and CKD. The results of the FIDELITY study demonstrate that finerenone provides significant renal and cardiovascular benefits in patients with T2D and CKD. Specifically, compared to placebo, finerenone reduces the risk of composite renal outcomes by 23%, significantly decreases proteinuria, and achieves a 32% greater reduction in urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline at 4 months of treatment [13]. Furthermore, finerenone decreases the risk of composite cardiovascular outcomes by 14% and significantly reduces the risk of hospitalization for heart failure by 22%. Importantly, the cardiovascular benefits associated with finerenone remain consistent, irrespective of whether patients had a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) at baseline. In terms of safety, the overall frequency of adverse events with finerenone is comparable to that observed with placebo. While the incidence of hyperkalemia is slightly elevated, the increase in potassium levels is modest, and the proportion of patients permanently discontinuing treatment due to hyperkalemia is low. Notably, no sex hormone-related adverse events were observed [126]. FIDELITY subgroup analysis demonstrates that the cardiovascular benefits and safety profile of finerenone in participants with stage 4 CKD were consistent with the overall FlDELITY population; this was also the case for albuminuria and the rate of eGFR decline [13]. Furthermore, the influence of finerenone on the prognosis of patients taking sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors was also evaluated in the pooled analysis of these pre-specified studies. The research discovered that, compared with placebo, the benefits of finerenone on the cardiorenal prognosis of patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes were independent of the use of SGLT2i [95]. Regarding the risk of hyperkalemia, we have clearly stated in the article the relationship between hyperkalemia risk and GFR, emphasizing that as the GFR decreases, the risk of hyperkalemia increases [127].

ARTS-HF is a Phase IIb, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, dose-exploration study utilizing active agents as comparators. The primary objective of this study was to comprehensively assess the differences in efficacy between finerenone and eplerenone by comparing these two drugs in terms of their ability to reduce the concentration of NT-proBNP, their safety profiles, and their potential impact on clinical endpoints. The findings indicated that finerenone, particularly at daily doses ranging from 2.5 to 10.0 mg, exhibited a more pronounced effect compared to eplerenone in lowering serum potassium concentration and mitigating the decline in eGFR. In patients with stable HFrEF and moderate CKD, finerenone demonstrated therapeutic efficacy comparable to eplerenone, as evidenced by significant reductions in NT-proBNP levels and proteinuria [128].

The FINEARTS-HF study is the first to explore the efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal MRAs in HFpEF/HFmrEF patients [129]. It is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III study. A total of 6001 patients with symptomatic heart failure (NYHA Grade II-IV) with LVEF ≥ 40% were enrolled at 653 research centers in 37 countries. The study showed that for the HFmrEF/HFpEF patient population, finerenone significantly reduces the risk of composite endpoints of total heart failure events and cardiovascular mortality by 18% and 16%, respectively, while improving life quality of patients. This benefit is consistent across different patient subgroups. In terms of safety, the incidence of serious adverse events is comparable between the finerenone group and the placebo group (38.7% vs. 40.5%, respectively). Notably, the use of finerenone increases the risk of hyperkalemia (9.7% vs. 4.2%), but correspondingly decreases the risk of hypokalemia (4.4% vs. 9.7%) [130]. It is worth mentioning that the lower the GFR, the greater the risk of hyperkalemia [127]. The FINEARTS-HF study not only assessed therapeutic efficacy but also conducted a detailed examination of the safety of combination therapy. The concurrent use of finerenone and SGLT2i demonstrated additional protective effects in the treatment of patients with HF. The study supports the complementary role of finerenone and SGLT2i in the treatment of HF and suggests that the combination of these two therapies may provide additional protection for patients with HF [131].

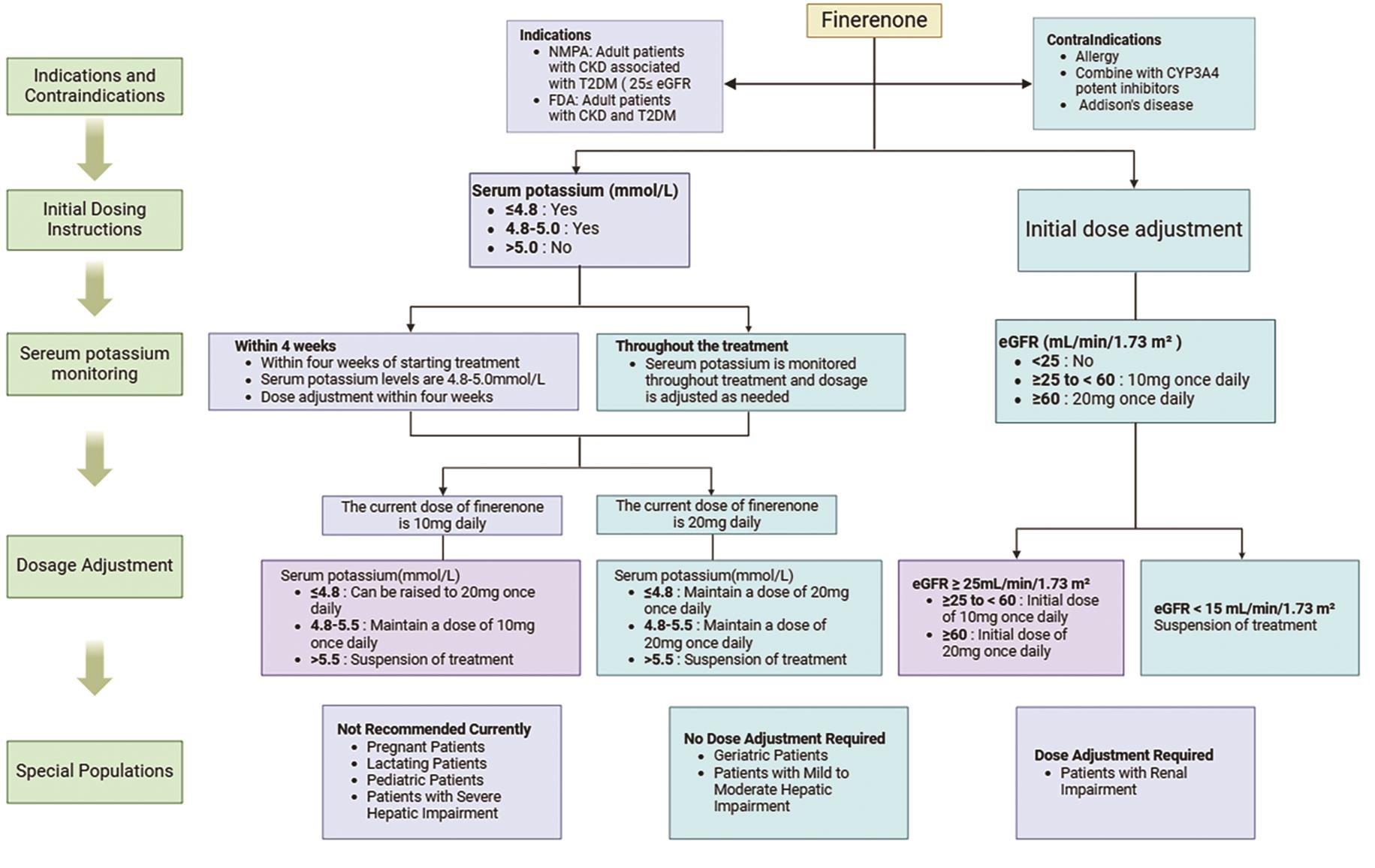

In conclusion, finerenone exhibits comprehensive benefits in the treatment of CRS. It significantly improves renal and cardiac functions while protecting multiple body systems through modulating inflammatory and fibrotic processes [112,132]. However, it is noteworthy that the specific effects of finerenone may vary among patients due to individual differences [133]. Therefore, when administering finerenone, it is imperative to tailor treatment plans based on the specific conditions and physiological characteristics of patients. Regularly monitoring relevant indicators to assess treatment efficacy and safety is also crucial [134]. By fully harnessing the multifaceted mechanisms of action of finerenone and adopting tailored treatment approaches, we can offer more precise and effective treatment options for patients with CRS, thereby improving their clinical outcomes and quality of life [13,134]. However, there remains insufficient research on its long-term effects and safety. Therefore, clinical medication should strictly comply with the principles of rational drug use and dose adjustment (Figure 4). Further studies are required to confirm its efficacy and safety across various patient populations.

7.Discussion and Prospect

Finerenone, an innovative achievement in modern medicine, distinguishes itself by its precise ability to block the excessive activation of MR [111]. This mechanism plays a pivotal role in the treatment of CRS, as it effectively inhibits inflammatory and fibrotic processes, thereby establishing a solid foundation for the restoration of cardiac and renal functions [135]. Finerenone boasts remarkable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, efficiently eliminating free radicals, reducing oxidative stress levels, and significantly inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators, thereby comprehensively alleviating heart and kidney damage [9,136]. Additionally, by optimizing microcirculation and expanding the vascular network, finerenone significantly enhances blood supply to the heart and kidneys, facilitating functional recovery of these vital organs [137]. Its unique physiological regulatory mechanism also manifests in precise modulation of renal tubular function, effectively maintaining dynamic electrolyte and fluid balance within the body, which is crucial for preserving overall cardiorenal system health [136,138].

Given the complex pathophysiology and high mortality rates associated with CRS, finerenone, with its multi-faceted protective mechanisms, has emerged as a promising new therapeutic option in this field [139]. Multiple internationally renowned large-scale clinical trials, such as FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, have robustly demonstrated the finerenone of superior efficacy and good safety profile in patients with T2DM and CKD [124,125]. These studies consistently show that finerenone can significantly reduce the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and renal events, including cardiovascular death, non-fatal stroke, heart failure hospitalization, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and renal failure, conferring substantial therapeutic benefits to patients with CRS [13,140]. According to the definition of CRS, Type 3 CRS pertains to sudden deterioration in renal function, such as acute renal ischemia or glomerulonephritis, which triggers acute cardiac dysfunction encompassing heart failure, arrhythmias, and ischemia [15,19]. Type 4 CRS describes a condition where CKD, for instance, chronic glomerular disease, results in diminished cardiac function, cardiac hypertrophy, and elevated risk of adverse cardiovascular events [21]. Therefore, since the initial disease is CKD, type 4 CRS is the main beneficiary according to the definition and characteristics of type 3 CRS and type4 CRS.

Despite the widely accepted classification scheme for CRS, there often remains a lack of clear delineation in clinical practice for the treatment and prognosis of various CRS subtypes. These subtypes frequently share certain primary or secondary pathogenic factors, thereby limiting their utility in clinical diagnosis and medication guidance [32]. We also acknowledge the significant role that finerenone plays in CRS treatment. However, we should adopt a more objective stance in evaluating its efficacy while paying close attention to its potential side effects and limitations, such as hyperkalemia and some unknown adverse events [141].

When assessing the efficacy of finerenone in CRS, existing research still has several evidence gaps. In particular, data on its efficacy and safety in specific CRS subtypes remains limited [111]. Furthermore, the effectiveness and safety of long-term treatment also require further research for confirmation. Additionally, there may be design limitations in existing studies, including insufficient sample sizes and inadequate follow-up durations [13]. The absence of extensive research evidence on cardiorenal diseases related to non-diabetic kidney disease poses a challenge to our comprehensive understanding of the efficacy and safety of finerenone [125]. Regarding the major adverse events associated with finerenone, although some studies have reported on them, further research is still necessary to confirm their incidence rates and types [141].

In light of the outstanding performance of finerenone in clinical trials, authoritative medical institutions like the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have incorporated it into relevant treatment guidelines as a recommended medication for patients with type 2 diabetes-related CKD [129,142]. This move not only further solidifies the crucial position of finerenone in treating CRS but also heralds its broad prospects for future clinical applications.

It is worth mentioning, though the classification of CRS is mainly based on the pathophysiological mechanism and clinical manifestations of the interaction between the heart and the kidney [143]. However, the contemporary management of CRS seemingly lacks specific, subtype-tailored treatment regimens. Specifically, in the case of acute CRS (types 1, 3, and 5), fundamental therapeutic strategies encompass the active management of heart failure, the maintenance of water, electrolyte, and acid-base homeostasis, the prevention or minimization of secondary renal insults such as renal hypoperfusion, nephrotoxic medications, and infections, the prompt addressing and prevention of acute complications, the reduction of mortality rates, and the prevention of the chronic progression of heart and/or renal failure [24]. On the other hand, in the context of chronic CRS (types 2 and 4), the primary focus is on the aggressive management of the underlying disease, the improvement of cardiac function, the mitigation of renal dysfunction progression, the prevention and management of chronic complications, the minimization or avoidance of CRS recurrences, and the enhancement of survival rates and quality of life [144,145]. Nonetheless, in the realm of clinical practice, these classifications may fail to provide substantial information regarding the mechanisms, treatment options, or prognostic outcomes associated with CRS, thus limiting their practical utility.

In conclusion, finerenone, with its unique multi-target therapeutic mechanism, dual protective effects on the cardiovascular and renal systems, robust clinical trial evidence, and endorsement by authoritative guidelines, has opened up a new therapeutic avenue for patients with CRS. It not only effectively alleviates symptoms and improves quality of life but also demonstrates significant potential in reducing disease risks and improving prognosis. Consequently, finerenone undoubtedly holds a pivotal position in the field of cardiorenal protection and is poised to become one of the mainstream treatment options in this domain in the future.

Author Contributions: H.D. and J.L.: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition; H.Z. (Hairui Zhao): writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing, visualization; C.P., X.C. and M.W.: writing—reviewing and editing. B.Q. and H.Z. (Hui Zhang): supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82400342, 82470295, 81470094, 81873556), Bethune Charitable Foundation (grant numbers HXJH-2022-10), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2024M761030).

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Acknowledgments: We thank our colleagues in Chen Chen’s group for technical assistance and stimulating discussions during the course of this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies: No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Patel, K.P; Katsurada, K; Zheng, H; Cardiorenal Syndrome: The Role of Neural Connections Between the Heart and the Kidneys . Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1601– 1617. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.122.319989.

- 2.

Ye, W.Q.W; Qureshi, M.A; Auguste, B; Cardiorenal syndrome . CMAJ 2023, 195, E 1154. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.230226.

- 3.

McCallum, W; Sarnak, M.J; Cardiorenal Syndrome in the Hospital . Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 933– 945. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.0000000000000064.

- 4.

Costanzo, M.R. The Cardiorenal Syndrome in Heart Failure . Heart Fail. Clin. 2020, 16, 81– 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2019.08.010.

- 5.

Epstein, M; Kovesdy, C.P; Clase, C.M; et al. Aldosterone, Mineralocorticoid Receptor Activation, and CKD: A Review of Evolving Treatment Paradigms . Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 658– 666. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.04.016.

- 6.

Lother, A. Mineralocorticoid Receptors: Master Regulators of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling . Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 354– 356. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.317424.

- 7.

Barrera-Chimal, J; Jaisser, F; Vascular and inflammatory mineralocorticoid receptors in kidney disease . Acta Physiol. 2020, 228, e 13390. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13390.

- 8.

Camarda, N.D; Ibarrola, J; Biwer, L.A; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Vascular Smooth Muscle: Blood Pressure and Beyond . Hypertension 2024, 81, 1008– 1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.21358.

- 9.

Barrera-Chimal, J; Bonnard, B; Jaisser, F; Roles of Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Cardiovascular and Cardiorenal Diseases . Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2022, 84, 585– 610. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-060821-013950.

- 10.

Mamazhakypov, A; Hein, L; Lother, A; Mineralocorticoid receptors in pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure: From molecular biology to therapeutic targeting . Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 231, 107987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107987.

- 11.

Finerenone: First Approval, J.E; . Drugs 2021, 81, 1787– 1794. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01599-7.

- 12.

Bakris, G.L; Agarwal, R; Anker, S.D; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes . N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2219– 2229. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2025845.

- 13.

Agarwal, R; Filippatos, G; Pitt, B; et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: The FIDELITY pooled analysis . Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 474– 484. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab777.

- 14.

Pitt, B; Filippatos, G; Agarwal, R; et al. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes . N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2252– 2263. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110956.

- 15.

Ronco, C; House, A.A; Haapio, M; Cardiorenal syndrome: Refining the definition of a complex symbiosis gone wrong . Intensive Care Med. 2008, 34, 957– 962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-008-1017-8.

- 16.

House, A.A; Anand, I; Bellomo, R; et al. Definition and classification of Cardio-Renal Syndromes: Workgroup statements from the 7th ADQI Consensus Conference . Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 1416– 1420. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfq136.

- 17.

Ronco, C; Cicoira, M; McCullough, P.A; Cardiorenal syndrome type 1: Pathophysiological crosstalk leading to combined heart and kidney dysfunction in the setting of acutely decompensated heart failure . J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1031– 1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.077.

- 18.

Jois, P; Mebazaa, A; Cardio-renal syndrome type 2: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment . Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 26– 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.11.004.

- 19.

Chuasuwan, A; Kellum, J.A; Cardio-renal syndrome type 3: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment . Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 31– 39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.11.005.

- 20.

Ruocco, G; Palazzuoli, A; Ter Maaten, J.M; The role of the kidney in acute and chronic heart failure . Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 107– 118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-019-09870-6.

- 21.

Granata, A; Clementi, A; Virzì, G.M; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome type 4: From chronic kidney disease to cardiovascular impairment . Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 1– 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.02.019.

- 22.

Soni, S.S; Ronco, C; Pophale, R; et al. Cardio-renal syndrome type 5: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment . Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 49– 56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.11.007.

- 23.

Hatamizadeh, P; Fonarow, G.C; Budoff, M.J; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: Pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management . Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2013, 9, 99– 111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2012.279.

- 24.

Rangaswami, J; Bhalla, V; Blair, J.E.A; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: Classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: A scientific statement from the american heart association . Circulation 2019, 139, e840– e878. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000664.

- 25.

Aronson, D; Darawsha, W; Promyslovsky, M; et al. Hyponatraemia predicts the acute (type 1) cardio-renal syndrome . Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 49– 55. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hft123.

- 26.

Ureña-Torres, P; D’Marco, L; Raggi, P; et al. Valvular heart disease and calcification in CKD: More common than appreciated . Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 2046– 2053. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz133.

- 27.

Xu, X; Zhang, B; Wang, Y; et al. Renal fibrosis in type 2 cardiorenal syndrome: An update on mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities . Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114901.

- 28.

Uchino, S; Kellum, J.A; Bellomo, R; et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational, multicenter study . JAMA 2005, 294, 813– 818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.7.813.

- 29.

Jankowski, J; Floege, J; Fliser, D; et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options . Circulation 2021, 143, 1157– 1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.050686.

- 30.

Ronco, C; McCullough, P; Anker, S.D; et al. Cardio-renal syndromes: Report from the consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative . Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 703– 711. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp507.

- 31.

Zannad, F; Rossignol, P; Cardiorenal Syndrome Revisited . Circulation 2018, 138, 929– 944. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.028814.

- 32.

Introducing Nephrocardiology, P; . Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 311– 313. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10940821.

- 33.

Schefold, J.C; Filippatos, G; Hasenfuss, G; et al. Heart failure and kidney dysfunction: Epidemiology, mechanisms and management . Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 610– 623. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2016.113.

- 34.

Zoccali, C; Mallamaci, F; Halimi, J.M; et al. From Cardiorenal Syndrome to Chronic Cardiovascular and Kidney Disorder: A Conceptual Transition . Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 19, 813– 820. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.0000000000000361.

- 35.

Gembillo, G; Visconti, L; Giusti, M.A; et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: New Pathways and Novel Biomarkers . Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1581. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11111581.

- 36.

Boorsma, E.M; Ter Maaten, J.M; Voors, A.A; et al. Renal Compression in Heart Failure: The Renal Tamponade Hypothesis . JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 175– 183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2021.12.005.

- 37.

Zhao, Y; Wang, C; Hong, X; et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates both heart and kidney injury in type 2 cardiorenal syndrome . Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 815– 829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.11.021.

- 38.

Ruiz-Hurtado, G; Ruilope, L.M; Cardiorenal protection during chronic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system suppression: Evidences and caveats . Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2015, 1, 126– 131. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvu023.

- 39.

Mentz, R.J; Stevens, S.R; DeVore, A.D; et al. Decongestion strategies and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in acute heart failure . JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 97– 107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.09.003.

- 40.

Albaghdadi, M; Gheorghiade, M; Pitt, B; Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism: Therapeutic potential in acute heart failure syndromes . Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2626– 2633. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr170.

- 41.

Cabandugama, P.K; Gardner, M.J; Sowers, J.R; The Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System in Obesity and Hypertension: Roles in the Cardiorenal Metabolic Syndrome . Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 129– 137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.009.

- 42.

Amador-Martínez, I; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E; Bernabe-Yepes, B; et al. Mitochondrial Impairment: A Link for Inflammatory Responses Activation in the Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 4 . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242115875.

- 43.

Jentzer, J.C; Bihorac, A; Brusca, S.B; et al. Contemporary Management of Severe Acute Kidney Injury and Refractory Cardiorenal Syndrome: JACC Council Perspectives . J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1084– 1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.070.

- 44.

Poveda, J; Vázquez-Sánchez, S; Sanz, A.B; et al. TWEAK-Fn14 as a common pathway in the heart and the kidneys in cardiorenal syndrome . J. Pathol. 2021, 254, 5– 19. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.5631.

- 45.

Doi, K; Noiri, E; Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiorenal Syndrome . Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016, 25, 200– 207. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2016.6654.

- 46.

Lu, N.Z; Wardell, S.E; Burnstein, K.L; et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXV. The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: Glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, progesterone, and androgen receptors . Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 782– 797. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.58.4.9.

- 47.

Sheppard, K.E. Nuclear receptors . II. Intestinal corticosteroid receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002, 282, G742– G746. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00531.2001.

- 48.

Oitzl, M.S; van Haarst, A.D; de Kloet, E.R; Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses controlled by the concerted action of central mineralocorticoid (MRS) and glucocorticoid receptors (GRS) . Psychoneuroendocrinology 1997, 22, S87– S93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00020-6.

- 49.

Pippal, J.B; Fuller, P.J; Structure-function relationships in the mineralocorticoid receptor . J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 41, 405– 413. https://doi.org/10.1677/jme-08-0093.

- 50.

Fardella, C.E; Miller, W.L; Molecular biology of mineralocorticoid metabolism . Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1996, 16, 443– 470. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.002303.

- 51.

Whaley-Connell, A; Johnson, M.S; Sowers, J.R; Aldosterone: Role in the cardiometabolic syndrome and resistant hypertension . Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 52, 401– 409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2009.12.004.

- 52.

Fuller, P.J; Yao, Y; Yang, J; et al. Mechanisms of ligand specificity of the mineralocorticoid receptor . J. Endocrinol. 2012, 213, 15– 24. https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-11-0372.

- 53.

Ruhs, S; Strätz, N; Schlör, K; et al. Modulation of transcriptional mineralocorticoid receptor activity by nitrosative stress . Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1088– 1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.028.

- 54.

Mahadik, N; Bhattacharya, D; Padmanabhan, A; et al. Targeting steroid hormone receptors for anti-cancer therapy-A review on small molecules and nanotherapeutic approaches . Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 14, e1755. https://doi.org/10.1002/wnan.1755.

- 55.

Wu, J; Luft, F.C; Mineralocorticoid-receptor signalling in vascular smooth muscle . Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 1360– 1362. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs562.

- 56.

Young, M.J; Rickard, A.J; Mechanisms of mineralocorticoid salt-induced hypertension and cardiac fibrosis . Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 350, 248– 255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.008.

- 57.

Caprio, M; Newfell, B.G; la Sala, A; et al. Functional mineralocorticoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and promote leukocyte adhesion . Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 1359– 1367. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.108.174235.

- 58.

Iovino, M; Messana, T; Lisco, G; et al. Signal Transduction of Mineralocorticoid and Angiotensin II Receptors in the Central Control of Sodium Appetite: A Narrative Review . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111735.

- 59.

Funder, J.W. Mineralocorticoid receptors: Distribution and activation . Heart Fail. Rev. 2005, 10, 15– 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-005-2344-2.

- 60.

De Kloet, E.R. Hormones and the stressed brain . Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1018, 1– 15. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1296.001.

- 61.

Trapp, T; Holsboer, F; Heterodimerization between mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors increases the functional diversity of corticosteroid action . Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 1996, 17, 145– 149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-6147(96)81590-2.

- 62.

Funder, J.W. Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors: Biology and clinical relevance . Annu. Rev. Med. 1997, 48, 231– 240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.231.

- 63.

Rivers, C.A; Rogers, M.F; Stubbs, F.E; et al. Glucocorticoid Receptor-Tethered Mineralocorticoid Receptors Increase Glucocorticoid-Induced Transcriptional Responses . Endocrinology 2019, 160, 1044– 1056. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2018-00819.

- 64.

Funder, J.W. Aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptors: Lessons from gene deletion studies . Hypertension 2006, 48, 1018– 1019. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.Hyp.0000249855.29529.84.

- 65.

Briet, M. Mineralocorticoid receptor, the main player in aldosterone-induced large artery stiffness . Hypertension 2014, 63, 442– 443. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.02581.

- 66.

Fettweis, G; Johnson, T.A; Almeida-Prieto, B; et al. The mineralocorticoid receptor forms higher order oligomers upon DNA binding . Protein. Sci. 2024, 33, e4890. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.4890.

- 67.

de Kloet, E.R; Van Acker, S.A; Sibug, R.M; et al. Brain mineralocorticoid receptors and centrally regulated functions . Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 1329– 1336. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00971.x.

- 68.

Kolkhof, P; Borden, S.A; Molecular pharmacology of the mineralocorticoid receptor: Prospects for novel therapeutics . Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 350, 310– 317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.025.

- 69.

Stier, C.T., Jr. Mineralocorticoid receptors in myocardial infarction . Hypertension 2009, 54, 1211– 1212. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.109.140384.

- 70.

Luther, J.M; Brown, N.J; The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and glucose homeostasis . Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 734– 739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2011.07.006.

- 71.

Davel, A.P; Jaffe, I.Z; Tostes, R.C; et al. New roles of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptors in cardiovascular disease: Translational and sex-specific effects . Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H989– H999. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00073.2018.

- 72.

Berger, S; Bleich, M; Schmid, W; et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor knockout mice: Lessons on Na+ metabolism . Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 1295– 1298. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00965.x.

- 73.

Armanini, D; Fiore, C; Calò, , L.A; Mononuclear leukocyte mineralocorticoid receptors . A possible link between aldosterone and atherosclerosis. Hypertension 2006, 47, e 4; replyauthor e4- 5. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.0000197933.23193.31.

- 74.

Luft, F.C. 11β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase-2 and Salt-Sensitive Hypertension . Circulation 2016, 133, 1335– 1337. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.116.022038.

- 75.

Chapman, K; Holmes, M; Seckl, J; 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: Intracellular gate-keepers of tissue glucocorticoid action . Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1139– 1206. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00020.2012.

- 76.

Zhao, R; Hong, L; Shi, G; et al. Mineralocorticoid promotes intestinal inflammation through receptor dependent IL17 production in ILC3s . Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 130, 111678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111678.

- 77.

Verma, A; Solomon, S.D; Optimizing care of heart failure after acute MI with an aldosterone receptor antagonist . Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2007, 4, 183– 189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-007-0011-8.

- 78.

Bienvenu, L.A; Reichelt, M.E; Morgan, J; et al. Cardiomyocyte Mineralocorticoid Receptor Activation Impairs Acute Cardiac Functional Recovery After Ischemic Insult . Hypertension 2015, 66, 970– 977. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.115.05981.

- 79.

Anker, S.D; Caprio, M; Vitale, C; Possible interactive effect of testosterone and aldosterone receptor antagonists on cardiac apoptosis . Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2010, 63, 760– 762. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70159-6.

- 80.

Blanner, P.M; Barve, R.A; Bolten, C.W; Mineralocorticoid receptors and vascular inflammation: New answers, new questions . Endocrinology 2007, 148, 1498– 1501. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-0104.

- 81.

Stojadinovic, O; Lindley, L.E; Jozic, I; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists-A New Sprinkle of Salt and Youth . J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 1938– 1941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.025.

- 82.

Shibata, S; Ishizawa, K; Uchida, S; Mineralocorticoid receptor as a therapeutic target in chronic kidney disease and hypertension . Hypertens. Res. 2017, 40, 221– 225. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.137.

- 83.

Barrera-Chimal, J; Andre-Gregoire, G; Dinh Cat, A.N; et al. Benefit of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism in AKI: Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Rac1 . J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1216– 1226. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016040477.

- 84.

Chang, Y; Ben, Y; Li, H; et al. Eplerenone Prevents Cardiac Fibrosis by Inhibiting Angiogenesis in Unilateral Urinary Obstruction Rats . J. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2022, 2022, 1283729. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1283729.

- 85.

Rickard, A.J; Morgan, J; Tesch, G; et al. Deletion of mineralocorticoid receptors from macrophages protects against deoxycorticosterone/salt-induced cardiac fibrosis and increased blood pressure . Hypertension 2009, 54, 537– 543. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131110.

- 86.

Usher, M.G; Duan, S.Z; Ivaschenko, C.Y; et al. Myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor controls macrophage polarization and cardiovascular hypertrophy and remodeling in mice . J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3350– 3364. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI41080.

- 87.

Young, M.J; Clyne, C.D; Mineralocorticoid receptor actions in cardiovascular development and disease . Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 901– 911. https://doi.org/10.1042/ebc20210006.

- 88.

Galuppo, P; Bauersachs, J; Mineralocorticoid receptor activation in myocardial infarction and failure: Recent advances . Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 42, 1112– 1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2012.02676.x.

- 89.

Fraccarollo, D; Geffers, R; Galuppo, P; et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor promotes cardiac macrophage inflammaging . Basic Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 243– 260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-024-01032-6.

- 90.

Stockand, J.D; Meszaros, J.G; Aldosterone stimulates proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts by activating Ki-RasA and MAPK1/2 signaling . Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003, 284, H176– H184. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00421.2002.

- 91.

Wang, Q; Cui, W; Zhang, H.L; et al. Atorvastatin suppresses aldosterone-induced neonatal rat cardiac fibroblast proliferation by inhibiting ERK1/2 in the genomic pathway . J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 61, 520– 527. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0b013e31828c090e.

- 92.

Epstein, M. Aldosterone and Mineralocorticoid Receptor Signaling as Determinants of Cardiovascular and Renal Injury: From Hans Selye to the Present . Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 209– 216. https://doi.org/10.1159/000515622.

- 93.

DuPont, J.J; Jaffe, I.Z; 30 Years of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor: The role of the mineralocorticoid receptor in the vasculature . J. Endocrinol. 2017, 234, T67– T82. https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-17-0009.

- 94.

Parfianowicz, D; Shah, S; Nguyen, C; et al. Finerenone: A New Era for Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism and Cardiorenal Protection . Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 47, 101386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101386.

- 95.

Rossing, P; Anker, S.D; Filippatos, G; et al. Finerenone in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes by Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor Treatment: The FIDELITY Analysis . Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2991– 2998. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-0294.

- 96.

Griesler, B; Schuelke, C; Uhlig, C; et al. Importance of Micromilieu for Pathophysiologic Mineralocorticoid Receptor Activity-When the Mineralocorticoid Receptor Resides in the Wrong Neighborhood . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232012592.

- 97.

Agarwal, M.K; Mirshahi, M; General overview of mineralocorticoid hormone action . Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 84, 273– 326. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00038-8.

- 98.

Hellal-Levy, C; Fagart, J; Souque, A; et al. Mechanistic aspects of mineralocorticoid receptor activation . Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 1250– 1255. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00958.x.

- 99.

Pitt, B; Kober, L; Ponikowski, P; et al. Safety and tolerability of the novel non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist BAY 94-8862 in patients with chronic heart failure and mild or moderate chronic kidney disease: A randomized, double-blind trial . Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2453– 2463. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht187.

- 100.

Dinh Cat, A.N; Friederich-Persson, M; White, A; et al. Adipocytes, aldosterone and obesity-related hypertension . J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2016, 57, F7– F21. https://doi.org/10.1530/jme-16-0025.

- 101.

Lowe, J; Kolkhof, P; Haupt, M.J; et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism by finerenone is sufficient to improve function in preclinical muscular dystrophy . ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 3983– 3995. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12996.

- 102.

Fejes-Tóth, G; Pearce, D; Náray-Fejes-Tóth, A; Subcellular localization of mineralocorticoid receptors in living cells: Effects of receptor agonists and antagonists . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2973– 2978. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.6.2973.

- 103.

Hernández-Díaz, I; Giraldez, T; Arnau, M.R; et al. The mineralocorticoid receptor is a constitutive nuclear factor in cardiomyocytes due to hyperactive nuclear localization signals . Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3888– 3899. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2010-0099.

- 104.

Shimojo, M; Ricketts, M.L; Petrelli, M.D; et al. Immunodetection of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in human mineralocorticoid target tissues: Evidence for nuclear localization . Endocrinology 1997, 138, 1305– 1311. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.138.3.4994.

- 105.

Li, X; Yang, A; Wen, P; et al. Nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group c member 2 (NR3C2) is downregulated due to hypermethylation and plays a tumor-suppressive role in colon cancer . Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 2669– 2679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-022-04449-6.

- 106.

Ruilope, L.M; Pitt, B; Anker, S.D; et al. Kidney outcomes with finerenone: An analysis from the FIGARO-DKD study . Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 372– 383. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfac157.

- 107.

Funder, J.W. The nongenomic actions of aldosterone . Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 313– 321. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2005-0004.

- 108.

Rico-Mesa, J.S; White, A; Ahmadian-Tehrani, A; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists: A Comprehensive Review of Finerenone . Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-020-01399-7.

- 109.

Kolkhof, P; Delbeck, M; Kretschmer, A; et al. Finerenone, a novel selective nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist protects from rat cardiorenal injury . J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 64, 69– 78.

- 110.

Jin, T; Fu, X; Liu, M; et al. Finerenone attenuates myocardial apoptosis, metabolic disturbance and myocardial fibrosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus . Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01064-3.

- 111.

González-Juanatey, J.R; Górriz, J.L; Ortiz, A; et al. Cardiorenal benefits of finerenone: Protecting kidney and heart . Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 502– 513. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2171110.

- 112.

Filippatos, G; Anker, S.D; Pitt, B; et al. Finerenone and Heart Failure Outcomes by Kidney Function/Albuminuria in Chronic Kidney Disease and Diabetes . JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 860– 870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2022.07.013.

- 113.

Messaoudi, S; Azibani, F; Delcayre, C; et al. Aldosterone, mineralocorticoid receptor, and heart failure . Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 350, 266– 272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.038.

- 114.

Haller, H; Bertram, A; Stahl, K; et al. Finerenone: A New Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Without Hyperkalemia: An Opportunity in Patients with CKD? Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2016, 18, 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-016-0649-2.

- 115.

Yao, L; Liang, X; Liu, Y; et al. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction via PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway in diabetic tubulopathy . Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102946.

- 116.

Swaab, D.F; Bao, A.M; Lucassen, P.J; The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration . Ageing Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 141– 194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003.

- 117.

Agarwal, R; Kolkhof, P; Bakris, G; et al. Steroidal and non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal medicine . Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 152– 161. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa736.

- 118.

Luther, J.M; Fogo, A.B; The role of mineralocorticoid receptor activation in kidney inflammation and fibrosis . Kidney Int. 2022, 12, 63– 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.006.

- 119.

Chang, W.T; Lin, Y.W; Chen, C.Y; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists Mitigate Mitral Regurgitation-Induced Myocardial Dysfunction . Cells 2022, 11, 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11172750.

- 120.

Ferreira, N.S; Tostes, R.C; Paradis, P; et al. Aldosterone, Inflammation, Immune System, and Hypertension . Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 15– 27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa137.

- 121.

Ong, G.S; Young, M.J; Mineralocorticoid regulation of cell function: The role of rapid signalling and gene transcription pathways . J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2017, 58, R33– R57. https://doi.org/10.1530/jme-15-0318.

- 122.

Blazek, O; Bakris, G.L; Slowing the Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease . Cells 2023, 12, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12151975.

- 123.

Liuzzo, G; Volpe, M; FIGARO-DKD adds new evidence to the cardiovascular benefits of finerenone across the spectrum of patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease . Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4789– 4790. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab725.

- 124.

Filippatos, G; Pitt, B; Agarwal, R; et al. Finerenone in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes with and without heart failure: A prespecified subgroup analysis of the FIDELIO-DKD trial . Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 996– 1005. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.2469.

- 125.

Filippatos, G; Anker, S.D; Agarwal, R; et al. Finerenone Reduces Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Analyses From the FIGARO-DKD Trial . Circulation 2022, 145, 437– 447. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.057983.

- 126.

Sarafidis, P; Agarwal, R; Pitt, B; et al. Outcomes with Finerenone in Participants with Stage 4 CKD and Type 2 Diabetes: A FIDELITY Subgroup Analysis . Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 602– 612. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.0000000000000149.

- 127.

Morales, E; Cravedi, P; Manrique, J; Management of Chronic Hyperkalemia in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: An Old Problem with News Options . Front. Med. 2021, 8, 653634. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.653634.

- 128.

Pitt, B; Anker, S.D; Böhm, M; et al. Rationale and design of MinerAlocorticoid Receptor antagonist Tolerability Study-Heart Failure (ARTS-HF): A randomized study of finerenone vs. eplerenone in patients who have worsening chronic heart failure with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease . Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 224– 232. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.218.

- 129.

Solomon, S.D; Ostrominski, J.W; Vaduganathan, M; et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: The FINEARTS-HF trial . Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 1334– 1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.3266.

- 130.

Mc Causland, F.R; Vaduganathan, M; Claggett, B.L; et al. Finerenone and Kidney Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure: The FINEARTS-HF Trial . J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 85, 159– 168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.091.

- 131.

Vaduganathan, M; Claggett, B.L; Kulac, I.J; et al. Effects of the Non-Steroidal MRA Finerenone with and without Concomitant SGLT2 Inhibitor Use in Heart Failure . Circulation 2025, 151, 149– 158. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.072055.

- 132.

Agarwal, R; Tu, W; Farjat, A.E; et al. Impact of Finerenone-Induced Albuminuria Reduction on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Mediation Analysis . Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 1606– 1616.

- 133.

Filippatos, G; Anker, S.D; Agarwal, R; et al. Finerenone and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes . Circulation 2021, 143, 540– 552. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.051898.

- 134.

Neuen, B.L; Heerspink, H.J.L; Vart, P; et al. Estimated Lifetime Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Mortality Benefits of Combination Treatment with SGLT2 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, and Nonsteroidal MRA Compared with Conventional Care in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Albuminuria . Circulation 2024, 149, 450– 462. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.123.067584.

- 135.

Ferrario, C.M; Schiffrin, E.L; Role of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiovascular disease . Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 206– 213. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.302706.

- 136.

Lattenist, L; Lechner, S.M; Messaoudi, S; et al. Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Finerenone Protects Against Acute Kidney Injury-Mediated Chronic Kidney Disease: Role of Oxidative Stress . Hypertension 2017, 69, 870– 878. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.116.08526.

- 137.

Ruilope, L.M; Agarwal, R; Anker, S.D; et al. Blood Pressure and Cardiorenal Outcomes with Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes . Hypertension 2022, 79, 2685– 2695. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.122.19744.

- 138.

Zhu, Z; Rosenkranz, K.A.T; Kusunoki, Y; et al. Finerenone Added to RAS/SGLT2 Blockade for CKD in Alport Syndrome. Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial with Col4a3-/- Mice . J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 1513– 1520. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.0000000000000186.

- 139.

Braam, B; Joles, J.A; Danishwar, A.H; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome--current understanding and future perspectives . Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 48– 55. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2013.250.

- 140.

Shi, Q; Nong, K; Vandvik, P.O; et al. Benefits and harms of drug treatment for type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials . BMJ 2023, 381, e074068. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-074068.

- 141.

Agarwal, R; Joseph, A; Anker, S.D; et al. Hyperkalemia Risk with Finerenone: Results from the FIDELIO-DKD Trial . J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 225– 237. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021070942.

- 142.

Beghini, A; Sammartino, A.M; Papp, Z; et al. 2024 update in heart failure . ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 8– 42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14857.

- 143.

Ronco, C; Haapio, M; House, A.A; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome . J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1527– 1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051.

- 144.

Gallo, G; Lanza, O; Savoia, C; New Insight in Cardiorenal Syndrome: From Biomarkers to Therapy . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065089.

- 145.

Cardiorenal Syndrome Guidelines Working Group of Chinese Nephrologist Association of Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cardiorenal syndrome (2023 Edition) . Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2023, 103, 3705– 3759. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20230822-00277.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.