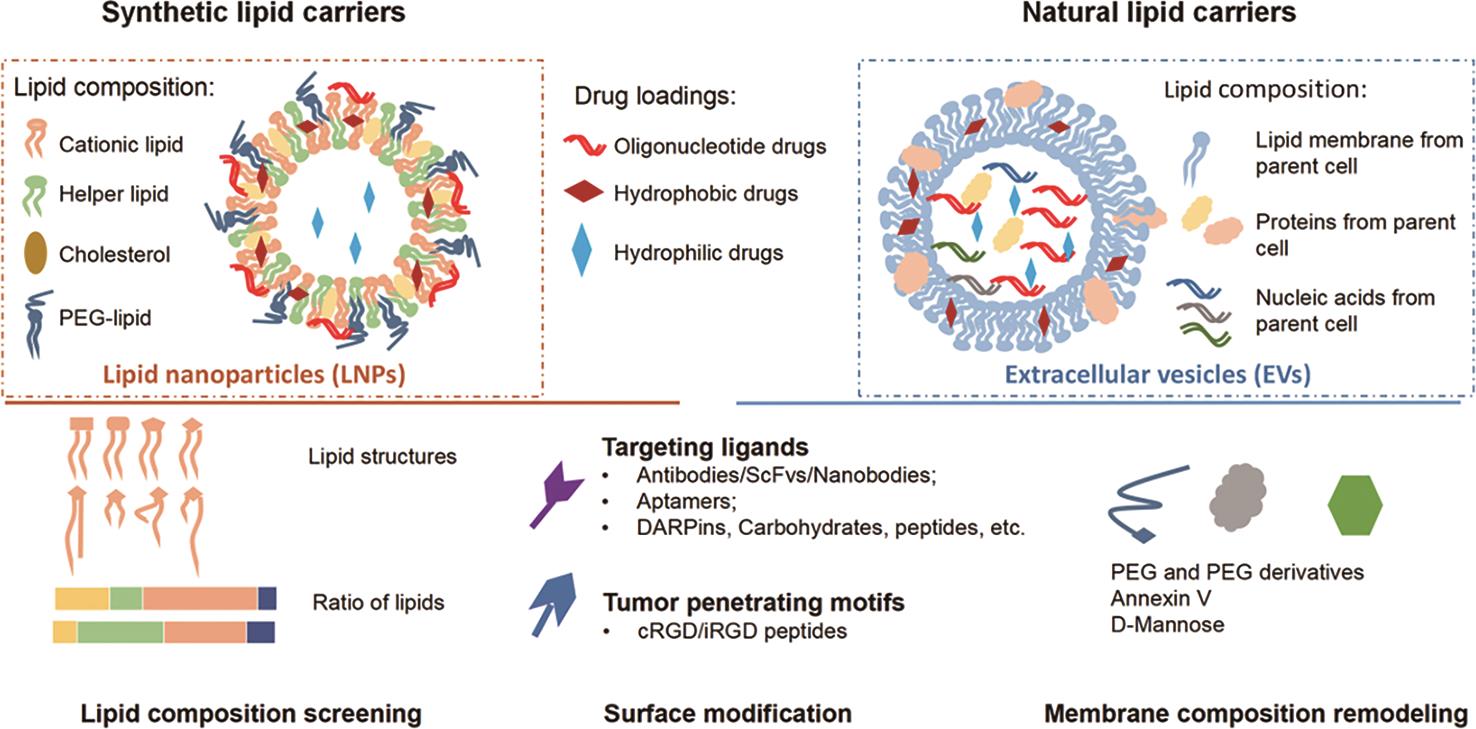

Lipid carriers are important pharmaceutical delivery systems for a variety of drugs. The primary advantage of lipid carriers lies in its ability to shield medicine cargos from proteolytic and phagocytic effects, and to facilitate delivery to tissues of interest. However, lipid carriers are also prone to systemic clearance and non-specific diffusion, thereby limiting their delivery rate to target tissues and the corresponding therapeutic efficacy. Recent research aimed at manipulating lipid membrane composition and targeting moiety has shown great promise for targeted delivery of cargo drugs. In this review, we discuss how synthetic lipid nanoparticles and naturally sourced extracellular vesicles such as exosomes are transformed with new technologies to enhance their pharmacological properties for the treatment of cancer.

- Open Access

- Review

Strategic Engineering of Lipid Drug Carriers for the Treatment of Cancer

- Shuyao Lang 1,*,†,

- Yunqing Li 2,*,†,

- Yi Kong 1,2,

- Youhai H. Chen 1,2,*

Author Information

Received: 26 Dec 2024 | Revised: 14 Mar 2025 | Accepted: 17 Mar 2025 | Published: 10 Nov 2025

Abstract

1.Introduction

With new advances in drug formulation and delivery technologies, nanomedicine has been advancing at a rapid pace and offering more effective therapeutic solutions to drug development [1–3]. Among diverse categories of nanomedicine, oligonucleotide-based medicine is small in size but significant for modulating biological functions, attracting interests from academia and industries for the treatment of various diseases [4,5] as highlighted by the 2024 Nobel-prized revelation of physiological functions of microRNAs. Oligonucleotides require protective carriers against enzymatic degradation, and clearance from circulation [1], underscoring the necessity for stable transportation by carriers in vivo. Lipid carriers, including lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes, have emerged as promising platforms for delivering therapeutic agents [1,6, 7]. partially due to their low immunogenicity and ease of manufacturing. Celebrated by the Nobel prize award for LNP-encapsulated mRNA vaccines, the importance of lipid nanocarriers in drug delivery of oligonucleotide cargos has been further appreciated.

In the context of anticancer therapy employing drug carriers, a common challenge is the restricted uptake of intravenously administered oligonucleotide drugs at tumor sites [8–13]. To address this challenge, strategies to improve the targeting ability and minimizing non-targeting effects of EVs and LNPs have been developed, which include engineering of the surface topology by modifying lipid composition or surface-decorating moieties [14–16]. In this review, we summarize and highlight ongoing lipid carrier strategies aimed at improving the efficacy of antitumor drugs.

2.Synthetic and Natural Lipid Carriers for Anti-Cancer Therapy

2.1.Lipid Nanoparticles

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are among the most studied artificial nano-drug delivery carriers. The first generation of LNPs, which often referred to as liposomes, was discovered in 1960s by Alec Bengham [17]. With the help of nanotechnology, the next generations of LNPs with noval lipid formulations and surface modifications for improved delivery and controlled drug release was soon under development [3,18,19]. Since 1995, the year when U.S. FDA approved the first LNP drug Doxil, a lipid nanoparticle encapsulating doxorubicin for ovarian cancer therapy, several LNP drugs have been approved for anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and anti-fungi therapies [18,19]. In recent years, LNPs for oligonucleotide delivery have started entering clinical markets. In 2018, the first LNP RNA interference drug for transthyretin amyloidosis therapy, Onpattro, was approved by FDA. Later, LNP-mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines Comirnaty and Spikevax were approved for the global clinical market [18].

LNPs that used as drug delivery carriers typically sized between 50–200 nm, which is similar in size to extracelluar vesicles (EVs). Both natural and synthetic lipids can serve as LNP components. By altering lipid compositions and fabrication, LNPs with tunable size can be designed for delivery of versatile cargo including oligonucleotides and small-molecule drugs. LNPs can be categorized into several types based on their nanostructures, including liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, and all types of LNPs are in development at pre-clinical, clinical and commercial level as drug delivery carriers. Toward bench-to-bed translation of LNP research products, stringent clinical GMP guidelines are available to standardize the protocols for large-scale manufacturing and pharmaceutical management of LNPs.

2.2.Lipid(oid)-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles

The hybrid nanoparticles that composed of lipids or lipid-like molecules (lipidoids) and polymers are emerging nano-drug delivery systems in recent years [20–23]. The lipid(oid)-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs) utilize the advantages of both lipid and polymer delivery systems: the biocompatibility, high drug loading capacity, and transfection efficiency of the lipid components, as well as the excellent mechanistic properties and drug releasing profile of the polymer materials. LPHNPs are popular drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. For example, a type of LPHNPs which contained redox-responsive poly(disulfide amide)(PDSA) core and a lipid shell consisting of a cationic lipidoid G0-C14 and two lipid-PEG compounds was used for the delivery of p53 mRNA into tumor cell and received significant therapeutic effect [24]. Benefiting from the distinct drug-loading property of lipids and polymers, LPHNPs are particularly suitable for dual delivery of drugs with completely different physicochemical properties, such as oligonucleotides and chemotherapy drugs, facilitating the combination therapy of cancer [21].

There are variable types of LPHNPs based on their architectures. The lipids and polymers can be mixed to form monolithic hybrid particles, and more commonly, the lipids and polymers are hybrid into core-shell structures, which can be further divided into four types: polymer core-lipid shell nanoparticles, lipid core-polymer shell nanoparticles (referred as polymer-caged lipid nanoparticles), hollow core lipid-polymer-lipid nanoparticles, and biomimetic nanoparticles with polymer core and cell membrane coating. Like lipid- and polymer-based drug carriers, the LPHNPs suggested promising safety profile and delivery efficacy in clinic. A COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, SW-BIC-213, which applied core-shell structured LPHNPs as a delivery system [25], was granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in Laos in 2022.

With the introduction of polymer materials, the physiochemical properties and pharmacokinetics of LPHNPs are distinct from the traditional lipid carriers. The synthesis and modification strategies of the two drug delivery systems are also significantly different from each other. There are already several excellent reviews about the lipid(oid)-polymer hybrid particles [20–22,26,27], and in this review, we would primarily focus on lipid delivery systems.

2.3.Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

Compared to the traditional nano-carrier LNPs, EVs are more recently explored nano-carriers with attractive properties for targeted drug delivery [7]. EVs encompass natural vesicles generated following invagination of plasma membrane and endosomal membrane, thereby inheriting bioactive components (e.g., oligonucleotides) as functional players from source cells [10,28]. Tumor cells or immune cells are selected as main cell sources for EV production in anticancer therapy. Whether tumor cells should be selected as the cell source for producing antitumor EVs is debatable. Tumor cell-sourced EVs garner favorable tumor-homing and immunostimulatory properties, but may have tumorigenic and immunosuppressive components that could counteract the anticancer effects of the drugs [1,12,29,30]. Tumor cell-sourced EVs can be ticking bombs to increase tumor burdens through blood circulation [12]. By contrast, immune cell-sourced EVs that carry natural antitumor components are preferably purposed to be lipid vehicles for delivering oligonucleotide in antitumor therapy [31–33].

2.4.Synthetic vs. Natural Lipid Particles: Pros and Cons

Synthetic LNPs and natural EVs as oligonucleotide cargo carriers have their own favorable properties and their disadvantages. Compared with LNPs, natural bioactive antitumor components from parent cells add therapeutic potentials and biocompatible values to EV-based antitumor therapy, but EVs are more difficult to produce at large scale with good product homogeneity. Whilst liposomes are more “druggable” with greater ease of manufacturing and higher homogeneity. Researchers have attempted structural modifications of these lipid carriers, and tried to use the favorable features of both types of carriers by making EV-like LNPs and LNP-like EVs.

Both LNPs and EVs as lipid carriers in vivo undergo a process of natural clearing from blood circulation through physical filtration and phagocytic digestion, primarily by the liver [34,35]. The remaining lipid carriers in blood circulation follow non-specific diffusion across various tissues, which further reduce bioavailability at tumor sites. Therefore, to improve bioavailability and to enhance tumor-targeting of lipid carriers are crucial for pharmacokinetic optimization toward translation into clinical applications.

3.Lipid Compositions for Enhanced Bioavailability and Targeting

3.1.Optimizing Lipid Membrane Composition Enhance the Circulatory Properties of both LNPs and EVs for Enhanced Bioavailablity

The in vivo pharmacokinetic stability and tumor retention properties of both LNPs and EVs are largely shaped by their lipid membrane composition and the decorating moieties crowning particles [15,16,18,36–38]. Systemic administration of particles in clinic is preferable but still far from practical. Like LNPs, systemically administered EVs suffer from fast clearance following phagocytic digestion by mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) and non-specific diffusion in non-targeted organs [31,39–41]. The clearance is even more profound for EVs than LNPs. As a result, the half-lives of EVs in circulation is very short (<1 h) and the bioavailability is limited [2,31]. Intrinsically poor tumor-targeting ability of natural EVs may explain why systemically administered EVs have yet to advance to phase III clinical trials. Optimizing lipid composition of these particles for improving pharmacokinetic properties such as tissue targeting is a straightforward and impactful strategy, shared in modifications of both LNPs and EVs.

3.2.Increasing Bioavailability by Rescuing Particles from Phagocytic Clearance

EVs and LNP as lipid-based carriers are inevitably subject to phagocytic clearance and diffusion into non-targeted tissues such as liver and lung. To minimize unnecessary loss of lipid carriers through phagocytic clearance and diffusion to non-targeted tissues is critical for enhancing tumor tissue uptakes [1,2,39]. Remodeling EV lipid membrane composition helps mask EVs from being tagged by MPS and allows for a larger portion of lipid carriers to accumulate at tumor sites. To avoid the depletion of EVs by MPS via the recognition of phosphatidylserine [39,42,43], the major lipid component of EV membrane, Matsumoto and colleagues introduced a high-affinity phosphatidylserine-binding protein annexin V, which competitively relieved EVs from macrophage binding and reduced non-specific liver accumulation of EVs [44]. This phenomenon was attributed to competitive charge neutralization. Similarly, PEG and its derivatives were added to EV surface by Antes and coworkers to sterically hinder the contact between phagocyte-recognizing spot (opsonin) and EV surface [41]. Collectively, by reducing non-targeted cellular uptake, surface functionalization of these lipid carriers can prolong their half-life in blood circulation [45].

3.3.Optimizating LNP Compositions for Enhanced Transfection Efficiency and Bioavailablity

In comparison, artificial particles LNPs have clearer and more controllable lipid composition than naturally produced EVs, which can be directly tailored for desirable pharmacokinetic properties. The current FDA approved LNPs for oligonucleotide drugs contain four lipid components [18]: an ionizable cationic lipid for nucleic acid loading, a helper phospholipid such as 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine (DSPC), a sterol lipid such as cholesterol for LNP formation and stabilization, and a PEG-conjugated lipid for surface shielding to prolong in vivo circulation. In exchange for the reduced toxicity, Dlin-MC3-DMA exhibited less efficient delivery rate compared to Dlin-KC2-DMA for DNA delivery [46]. Therefore, lipid compositions should be carefully screened and selected in order to achieve optimized therapeutic effect.

3.3.1.Cationic Lipids

Cationic lipids are the key components for nucleic acid loading and transfection. The early examples of LNPs usually include cationic lipids with permanent charges in physiological pH, such as (2,3-Dioleoyloxy-propyl)-trimethylammonium-chloride, (2,3-Dioleyl-propyl)-trimethylamine (DOTAP), 1,2-di-O-octadecenyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTMA), 3β[N(N’,N’Dimethylaminoethane)carbamoyl]cholesterol (DC-Chol). Later, ionizable lipids with pKa value ranged 6.2–6.5 were developed and widely applicated in research and clinic uses [47]. These ionizable lipids are cationic under acidic condition for sufficient nucleic acid loading, and are neutral under physiological pH for reduced clearance and toxicity. These ionizable lipids would gain positive charges again in the acidic condition of lysosomes and facilitate the escape of cargoes from the lysosomes for enhanced transfection efficiency. The first FDA approved siRNA drug Onpattro was composite with ionizable cationic lipid Dlin-MC3-DMA, and the Moderna COVID vaccine used another ionizable cationic lipid, SM-102, for mRNA delivery. Notably, the cationic lipids that are screened for siRNA delivery may not be the optimized one for mRNA or DNA delivery. For example, Dlin-MC3-DMA outperformed its structurally similar lipid Dlin-KC2-DMA for siRNA delivery, but exhibited less efficient delivery rate for DNA delivery [46,47]

3.3.2.Cholesterol and Cholesterol Analogues

Cholesterol and its analogues are important components for adjusting the fluidity of lipid bilayers as well as the morphology of LNPs, which further influence the cellular recognition and membrane fusion properties [48,49]. Therefore, cholesterol and analogues can significantly impact the intracellular transfection efficiency of LNPs. Sahay lab screened a collection of LNPs containing various cholesterol and cholesterol analogues for enhanced drug packaging and transfection efficiency. They noted a cholesterol analogue, β-sitosterol, enhanced the mRNA transfection of LNPs while maintaining a similar encapsulation rate compared to cholesterol LNPs [49]. Compared to spherical cholesterol LNPs, β-sitosterol-substituted LNPs were polymorphically shaped to induce a higher cellular uptake and retention. Dahlman lab reported the influence of the stereochemistry of cholesterol on endocytic process of LNPs [50]. Though LNPs with racemic mixture of cholesterol or 20α cholesterol shared similar physical properties, the cells that exposed to the two LNPs responded differently. The LNPs with racemic cholesterol were associated with higher expression levels of phagocytic and proinflammatory genes, driving a reduced in vivo mRNA delivery efficiency compared to the LNPs with 20α cholesterol. This finding emphasized the importance of stereochemistry of cholesterol on intracellular process of the LNPs.

3.3.3.Helper Phospholipids

The helper phospholipids support the formation of lipid bilayers and are known to contribute to the stability, RNA packaging and transfection efficiency of LNPs [51,52]. Helper lipids with varying polar heads and alkyl tails contribute to different membrane structures. For instance, DOPE imparts cone-shaped geometry while DOPC and DSPC imparts clindrical geometry [51]. The helper phospholipids also contribute to the immunogenicity of LNPs. Shattock lab investigated the roles of DOPC, DSPC and DOPE in being helper lipids in LNPs and recognized distinct cytokine profile in vitro and in vivo [51]. Yet, the relationship between cytokine profile and overall efficacy of LNPs has remained unclear and required further study.

3.3.4.PEG-Conjugated Lipids

PEG-conjugated lipids are important for the protection of LNPs during circulation. Although the fraction of PEG-conjugated lipids in LNPs is small (typically 0.5–3 mol%), the PEG-conjugated lipids still have significant impacts on the pharmaceutical properties of LNPs. For example, 1.5 mol% of PEG-conjugated lipids with different carbon chain length (14, 16 and 18) strongly influenced the circulation time in blood (t1/2 = 0.64 h, 2.18 h and 4.03 h, respectively) and liver accumulation (871.8, 566.6 and 373.5 μg lipid per gram liver tissue in 24 h, respectively) [53]. Thus, the PEG-conjugated lipids in LNPs should also be carefully evaluated for a balanced stability and transfection efficiency [54,55].

3.4.Optimizing the LNP Components for Ligand-Free Targeting Delivery

To date, many efforts have been made to formulate LNPs over EVs, owing to its particular advantages in ease to product manipulation, manufactural standardization and management. High-throughput standardized screening method can be applied for screening LNPs for enhanced tissue-targeted delivery vehicles that target beyond hepatocytes, where the lipid carriers naturally accumulate. One of the strategies for tuning the targeting preference of LNPs is the screening of particular lipid chemical structures with desired targeting selectivity. Dahlman lab investigated 141 LNPs, which were formulated with 6 cholesterol variants (unmodified, esterified or oxidized) and 10 phospholipids at 8 different formulation ratios, by a high-throughput DNA barcoding in vivo screening system [56]. It was noted that cholesterol esterification generally improved drug delivery across different organs and cell types. Notably, they found one of the esterified cholesterols, cholesteryl oleate, selectively delivered sgRNA into hepatic endothelial cells over hepatocytes [56]. Later, Dahlman lab expanded their in vivo screening of targeting LNPs. They synthesized 13 ionizable lipids containing amines or boronic acid, and then prepared over 100 different LNPs with these 13 synthetic lipids and helper lipids [57]. The in vivo screening of these LNPs revealed a synthetic lipid, 11-A-M, which contained a diethylamino head, an adamantane tail and a linoleic acid tail, had stronger interaction with splenic T cells than with hepatocytes or liver endothelial cells. LNPs constructed with 11-A-M, cholesterol, DSPC and C14-PEG2000 successfully delivered siRNA and sgRNA to splenic T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, with few off-target effect on other cell types or tissues [57]. Xu lab designed and synthesized a library of lipidoids with 19 different heads and 13 different tails for the targeting delivery toward human primary CD8+ T cells [58]. After a rough screening, lipids containing 1-[3-Aminopropyl]imidazole head showed effective CD8 targeting delivery with various tails, indicating the targeting potential of imidazole heads. A follow-up detailed screening of 18 imidazole analogues as lipid heads was then performed. It was found that the lipidoid 93-O17S, which including an imidazole head and two sulfur substituted 17-carbon tails, had significant accumulation in spleen but not liver or other organs. Cre mRNA was delivered at ~8.2% delivery rate in splenic CD4+ T cells and ~6.5% in splenic CD8+ T cells. Xu lab also identified another lipidoid 113-O12B which has preferential targeting towards dendritic cells and macrophages in lymph nodes [59].

On the basis of the existing lipid library, the LNP targeting preference can also be rewired for targeting different tissues in a de novo strategy. Siegwart lab reported a selective organ-targeting strategy (SORT) for LNP formulation [60]. They introduced a fifth lipid component termed SORT molecules into the traditional four-component LNPs. By the introduction of different SORT molecules, the final five-component LNPs showed different targeting abilities. The addition of anionic SORT molecule, 18 PA, mediated completely selective delivery to the spleen, while the cationic SORT molecules DOTAP aided lung targeting [60]. Liu lab investigated a novel type of ionizable lipids with biodegradable ester-cores (nAcx-Cm) [61]. Interestingly, they found the cholesterol and helper phospholipid were not essential for LNP formulation in their system. The nAcx-Cm LNPs omitting cholesterol and phospholids showed targeting ability toward lung and spleen, while the cholesterol-containing nAcx-Cm LNPs favored liver delivery. Simply by optimizing the lipid compositions, LNPs and EVs with different organ/cell targeting selectivity can be achieved without additional aids from targeting ligands, which provides straightforward options for developing targeted platforms for anti-tumor therapy in different organs.

4.Surface Modifications for Enhanced Targeting and Tumor-Penetrating Properties

The passive targeting of LNPs and EVs toward tumor is typically not sufficient enough for solid tumor therapy. A review of the recent studies showed that on average only ~0.7% of the intravenously administrated nanoparticles reached solid tumorsites [62], equivalently at a dose threshold as high as 1 trillion nanoparticles in mice [63]. Besides optimizing the lipid composition of LNPs and EVs, another common strategy for improving targeting ability is the surface engineering of these particles [12,13]. Many surface engineering strategies have been attempted for both LNPs and EVs. For example, targeting ligands can be directly conjugated to reactive groups on LNPs or EVs surface through affinity-based interaction (e.g., biotin-streptavidin interaction) or covalent conjugation by chemical and enzymatic ligation (e.g., ligase-dependent reaction) [13,16,64,65]. A more straightforward way is post-insertion, which introduces entire ligand-conjugated lipids onto the preformed LNPs or EVs through co-incubation [65–68]. An alternative option of surface modification for EVs is genetic or metabolic modification of the parent cells. For example, exosomes isolated from azido-containing labeling reagent Ac4ManNAz-treated GL261 (murine glioblastoma multiforme cells) also bears azido groups on their membrane [69]. Endogenously modified EVs require no external treatments, but successful modification rate largely varies among different batches and different studies.

Various types of targeting ligands including antibodies, peptides, carbohydrates, aptamers and DARPins, can be applied for LNPs and EVs modification. Antibody-conjugates are the most prominent tumor-targeting solution, with attribute of their high specificity and affinity for particular structures of interest [7,39]. The conventional targeting antibodies inducing direct tumor lysis include the antibodies against tumor-specific antigens or tumor-associated antigens [3,13], such as HER2 [14,70], ER [71], EGFR [72,73], VEGFR2 [74], CD44 [75], etc. Manipulating the immunodynamics can be a “sidekick” of indirect attack on tumor. The most commonly selected targets are surface markers on immune cells, e.g., CD3, CD4 and CD8 on T cells [76-78]. Particles may carry multiple targeting moieties for bridging tumor and immune cells for an enhanced anti-tumor immunity. For example, Zhang and colleagues genetically engineered exosome-producing Expi293 cells which produce EVs expressing both anti-CD3 and anti-HER2 (referred as SMART-Exo) [14,74]. The resulting SMART-Exo significantly aggregated Jurkat and HER2+ tumor cell lines, and induced significant T cell activation. In agreement with the in vitro results, the SMART-Exo induced marked CD3+ T cell infiltration in tumors and efficiently limited tumor growth in vivo [14].

Besides targeting antibodies, aptamers is another emerging category of high-specificity and tumor-targeting moieties which have drawn enormous interest from academia and industry. Aptamers are selected from high-throughput screening methodology, namely systematic evaluation of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) [79–81], where single-stranded aptamer candidates of high selectivity and high affinity are pooled and enriched [81–83]. Aptamers are designed to recognize particular three-dimensional structures varied from proteins, nucleotides to whole cells [82,83]. Since successful clinical approvals of aptamers by FDA [84], researchers have been endeavoring to take advantage of the specificity of aptamers in developing EVs. Aptamers are believed to be employed as an ideal targeting moiety with high tissue-penetrating ability and tumor selectivity superior to antibody conjugates [85–87]. Esposito and coworkers incorporated breast cancer cell-derived EVs with 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA aptamer for breast cancer targeting. They reported that such EV product has high selectivity ex vivo for primary breast cancer cells over normal breast tissues [88]. Another noted significance of aptamers to EV therapeutics was seen in an aptamer-oriented macrophage EVs for glioblastoma [89]. Wu et al. took use of a well-characterized aptamer AS1411 that specifically recognized cancer-associated surface protein nucleolin, and validated the importance of apatamer in improvement in tumor-targeting ability of EVs. Taken advantage of their high specificity towards targets, aptamers can be utilized as a smart tool for capturing cancer-specific structures with circumvention of adverse effects and unnecessary EV uptake in non-targeted tissues [86].

Tumor-penetrating motifs confer tumor intravasation following the initial recognition step by interacting with tumor cell surface. A representative example refers to cyclic peptide containing Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD), which has been incorporated into lipid carriers as a tumor-penetrating motif in antitumor treatments [90]. Following association with tumor surface marker αVβ3 integrin molecule, RGD-linked lipid nanocarriers are more readily internationalized into tumor tissues with better cargo delivery rate [91]. An improved version of RGD peptide, noted as iRGD (CRGDK/RGPD/EC), is also commonly introduced in anti-tumor delivery systems [92]. Compared to cRGD, the iRGD peptide binds another tumor marker NRP-1 when proteolytically cleaved by tumor after initial binding with αVβ3 integrin, which leads to a further tumor penetration [92,93]. This is attributed to enhanced permeability retention effect (EPR), by which nano-sized particles are naturally born with an advantage of entering leaky blood vessels lining vascularized tumor tissues [90]. In addition to ligand addition, the source of EVs preserves an added advantage in targeting the source tissue with attribute of their homing ability. Wang et al. reported a successful targeted delivery for gliobalstoma with microglial cell-derived exosomes as the drug vehicle, with excellent penetrating rate across the blood-brain-barrier [69].

5.Future Perspectives

Accumulating research in recent years have investigated lipid particles with efficient in vivo targeting ability toward tumor or immune tissues. This review gathers and discusses functional studies on how tumor-targeting ability of LNPs and EVs is shaped by the following two factors: (1) lipid composition and (2) surface modification of the particles. (Summarized in Figure 1). Several tricky issues have been addressed. First, in vitro screening of tissue-targeting lipids remains as a common strategy in current studies. Though in vitro screening experiments for tumor-targeting lipid carriers is cost-effective for most cases, the in vivo performance of the lipids identified by in vitro screening is not always satisfactory [94]. Therefore, high-throughput in vivo screening with facility of the DNA barcodes and modern sequencing technologies can be a possible alternative solution to less informative in vitro screening [56,57]. Second, it should be noted that targeting ligands modified on LNPs and EVs may induce undesired interactions and stimulation on target cells. For example, during successful engineering of T cells in vivo, anti-CD3 antibody conjugated LNPs induced undesired splenic T cells migration and phenotype shifts [78]. Potential risks of tropism of EV carriers and unknown impacts on non-targeted tissues are critical pharmacological properties to be well characterized for clinical study. Third, in vivo immunogenicity of lipid carriers, particularly LNPs containing non-natural lipid structures, should be carefully evaluated [95]. Highly immunogenic lipids are double-edged swords in anticancer therapies: LNP carriers may serve as adjuvants for inducing strong anti-tumor immunity, whilst potentially inducing exaggerated immune responses and consequent resistance after multiple administrations. Adverse effects such as allergy and autoimmune diseases may occur after the administration of LNPs due to the immunogenic components [94-96]. As lipid-based drug carriers progress toward clinical use, their safety and regulatory approval will be crucial. Comprehensive studies on the long-term effects, immunogenicity, and toxicology of lipid carriers are essential for their successful translation into clinical use. Tumor cells exhibit significant heterogeneity, which can affect the efficiency of targeted drug delivery. Overcoming this challenge will require the development of more sophisticated targeting strategies and personalized approaches.

6.Conclusions

The strategic engineering of lipid drug carriers presents substantial potential for the advancement of cancer therapy. Through the manipulation of lipid composition and the functionalization of surface properties, researchers are developing more efficient and targeted drug delivery systems aimed at enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of cancer treatments. As these technologies evolve and surmount existing obstacles, lipid carriers are anticipated to become a fundamental component of precision medicine in oncology.

Author Contributions: Y.H.C., Y.L. and S.L.: concepted the topic; S.L. and Y.L.: wrote the original draft of the manuscript; Y.H.C. and Y.K.: reviewed and edited the manuscript; Y.H.C.: supervised this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA0912400), the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2301006, B2404003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32130040, 82250710172), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220818100806015, JCYJ20220531100205011, JCYJ20240813161113018, JCYJ20220530154215035), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515110037).

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: Y.H.C. is a member of the boards of Amshenn Inc. and Binde Inc. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies: No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Wu, P; Zhang, B; Ocansey, D.K.W; et al. Extracellular vesicles: A bright star of nanomedicine . Biomaterials 2021, 269, 120467.

- 2.

Clemmens, H; Lambert, D.W; Extracellular vesicles: Translational challenges and opportunities . Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1073– 1082.

- 3.

Hannon, G.J; Rossi, J.J; Unlocking the potential of the human genome with RNA interference . Nature 2004, 431, 371– 378.

- 4.

Roberts, T.C; Langer, R; Wood, M.J.A; Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery . Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 673– 694.

- 5.

Mehta, M; Bui, T.A; Yang, X; et al. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Drug/Gene Delivery: An Overview of the Production Techniques and Difficulties Encountered in Their Industrial Development . ACS Mater. Au 2023, 3, 600– 619.

- 6.

Wang, Z; Mo, H; He, Z; et al. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging drug delivery system for cancer treatment: Current strategies and recent advances . Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113480.

- 7.

Németh, K; Varga, Z; Lenzinger, D; et al. Extracellular vesicle release and uptake by the liver under normo- and hyperlipidemia . Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 7589– 7604.

- 8.

Li, J; Zhang, H; Jiang, Y; et al. The landscape of extracellular vesicles combined with intranasal delivery towards brain diseases . Nano Today 2024, 55, 102169.

- 9.

Kalluri, R; LeBleu, V.S; The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes . Science 2020, 367, eaau 6977.

- 10.

Sousa, D; Ferreira, D; Rodrigues, J.L; et al. Chapter 14—Nanotechnology in Targeted Drug Delivery and Therapeutics. In Applications of Targeted Nano Drugs and Delivery Systems; Dasgupta, N., Mishra, R.K., Thomas, S., et al., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 357– 409.

- 11.

Cheng, X; Henick, B.S; Cheng, K; Anticancer Therapy Targeting Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles . ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6748– 6765.

- 12.

Zahednezhad, F; Allahyari, S; Sarfraz, M; et al. Liposomal drug delivery systems for organ-specific cancer targeting: Early promises, subsequent problems, and recent breakthroughs . Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2024, 21, 1363– 1384.

- 13.

Shi, X; Cheng, Q; Hou, T; et al. Genetically Engineered Cell-Derived Nanoparticles for Targeted Breast Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 536– 547.

- 14.

Zhang, X; Sun, Y; Chen, W; et al. Nanoparticle functionalization with genetically-engineered mesenchymal stem cell membrane for targeted drug delivery and enhanced cartilage protection . Biomater. Adv. 2022, 136, 212802.

- 15.

Smyth, T; Petrova, K; Payton, N.M; et al. Surface Functionalization of Exosomes Using Click Chemistry . Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 1777– 1784.

- 16.

Bangham, A.D; Horne, R.W; Negative staining of phospholipids and their structural modification by surface-active agents as observed in the electron microscope . J. Mol. Biol. 1964, 8, 660-IN 10.

- 17.

Albertsen, C.H; Kulkarni, J.A; Witzigmann, D; et al. The role of lipid components in lipid nanoparticles for vaccines and gene therapy . Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114416.

- 18.

Nsairat, H; Khater, D; Sayed, U; et al. Liposomes: Structure, composition, types, and clinical applications . Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394.

- 19.

Date, T; Nimbalkar, V; Kamat, J; et al. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanocarriers for delivering cancer therapeutics . J. Control. Release 2018, 271, 60– 73.

- 20.

Gajbhiye, K.R; Salve, R; Narwade, M; et al. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: A custom-tailored next-generation approach for cancer therapeutics . Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 160.

- 21.

Li, X; Qi, J; Wang, J; et al. Nanoparticle technology for mRNA: Delivery strategy, clinical application and developmental landscape . Theranostics 2024, 14, 738– 760.

- 22.

Jansen, M.A.A; Klausen, L.H; Thanki, K; et al. Lipidoid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles loaded with TNF siRNA suppress inflammation after intra-articular administration in a murine experimental arthritis model . Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 38– 48.

- 23.

Kong, N; Tao, W; Ling, X; et al. Synthetic mRNA nanoparticle-mediated restoration of p53 tumor suppressor sensitizes p53-deficient cancers to mTOR inhibition . Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw1565.

- 24.

Gui, Y.Z; Li, X.N; Li, J.X; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, SW-BIC-213, as a heterologous booster in healthy adults: An open-labeled, two-centered and multi-arm randomised, phase 1 trial . EBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104586.

- 25.

Kassaee, S.N; Richard, D; Ayoko, G.A; et al. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles against lung cancer and their application as inhalable formulation . Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 2113– 2133.

- 26.

Sunoqrot, S; Abdel Gaber, S.A; Abujaber, R; et al. Lipid- and Polymer-Based Nanocarrier Platforms for Cancer Vaccine Delivery . ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 4998– 5019.

- 27.

Nieuwland, R; Falcon‐Perez, J.M; Soekmadji, C; et al. Essentials of extracellular vesicles: Posters on basic and clinical aspects of extracellular vesicles . J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1548234.

- 28.

Herrmann, I.K; Wood, M.J.A; Fuhrmann, G; Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform . Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748– 759.

- 29.

Zuo, B; Qi, H; Lu, Z; et al. Alarmin-painted exosomes elicit persistent antitumor immunity in large established tumors in mice . Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1790.

- 30.

Choi, S.J; Cho, H; Yea, K; et al. Immune cell-derived small extracellular vesicles in cancer treatment . BMB Rep. 2022, 55, 48– 56.

- 31.

Federici, C; Shahaj, E; Cecchetti, S; et al. Natural-Killer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Immune Sensors and Interactors . Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 262.

- 32.

Lugini, L; Cecchetti, S; Huber, V; et al. Immune surveillance properties of human NK cell-derived exosomes . J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 2833– 2842.

- 33.

Morishita, M; Takahashi, Y; Nishikawa, M; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Tissue Distribution of the B16BL6-Derived Exosomes Using a Streptavidin-Lactadherin Fusion Protein and Iodine-125-Labeled Biotin Derivative After Intravenous Injection in Mice . J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 705– 713.

- 34.

Hwang, D.W; Choi, H; Jang, S.C; et al. Noninvasive imaging of radiolabeled exosome-mimetic nanovesicle using 99mTc-HMPAO . Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15636.

- 35.

Sun, D; Zhuang, X; Xiang, X; et al. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: The anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes . Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1606– 1614.

- 36.

Alfutaimani, A.S; Alharbi, N.K; Alahmari, A.S; et al. Exploring the landscape of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): A comprehensive review of LNPs types and biological sources of lipids . Int. J. Pharm. X 2024, 8, 100305.

- 37.

Tenchov, R; Bird, R; Curtze, A.E; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles horizontal line From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Delivery, a Landscape of Research Diversity and Advancement . ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982– 17015.

- 38.

Ferreira, D; Moreira, J.N; Rodrigues, L.R; New advances in exosome-based targeted drug delivery systems . Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 172, 103628.

- 39.

Wiklander, O.P.B; Nordin, J.Z; O’Loughlin, A; et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting . J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26316.

- 40.

Antes, T.J; Middleton, R.C; Luther, K.M; et al. Targeting extracellular vesicles to injured tissue using membrane cloaking and surface display . J. Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 61.

- 41.

Segawa, K; Nagata, S; An Apoptotic ‘Eat Me’ Signal: Phosphatidylserine Exposure . Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 639– 650.

- 42.

Matsumura, S; Minamisawa, T; Suga, K; et al. Subtypes of tumour cell-derived small extracellular vesicles having differently externalized phosphatidylserine Mannose-Modified Serum Exosomes for the Elevated Uptake to Murine Dendritic Cells and Lymphatic Accumulation . J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1579541.

- 43.

Matsumoto, A; Takahashi, Y; Nishikawa, M; et al. Role of Phosphatidylserine-Derived Negative Surface Charges in the Recognition and Uptake of Intravenously Injected B16BL6-Derived Exosomes by Macrophages . J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 168– 175.

- 44.

Smyth, T; Kullberg, M; Malik, N; et al. Biodistribution and delivery efficiency of unmodified tumor-derived exosomes . J. Control. Release 2015, 199, 145– 155.

- 45.

Kulkarni, J.A; Myhre, J.L; Chen, S; et al. Design of lipid nanoparticles for in vitro and in vivo delivery of plasmid DNA . Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 1377– 1387.

- 46.

Jayaraman, M; Ansell, S.M; Mui, B.L; et al. Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8529– 8533.

- 47.

Zhang, Y; Li, Q; Dong, M; et al. Effect of cholesterol on the fluidity of supported lipid bilayers . Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 196, 111353.

- 48.

Patel, S; Ashwanikumar, N; Robinson, E; et al. Naturally-occurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA . Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 983.

- 49.

Hatit, M.Z.C; Dobrowolski, C.N; Lokugamage, M.P; et al. Nanoparticle stereochemistry-dependent endocytic processing improves in vivo mRNA delivery . Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 508– 515.

- 50.

Barbieri, B.D; Peeler, D.J; Samnuan, K; et al. The role of helper lipids in optimising nanoparticle formulations of self-amplifying RNA . J. Control. Release 2024, 374, 280– 292.

- 51.

Zimmer, D.N; Schmid, F; Settanni, G; Ionizable Cationic Lipids and Helper Lipids Synergistically Contribute to RNA Packing and Protection in Lipid-Based Nanomaterials . J. Phys. Chem. B. 2024, 128, 10165– 10177.

- 52.

Mui, B.L; Tam, Y.K; Jayaraman, M; et al. Influence of Polyethylene Glycol Lipid Desorption Rates on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of siRNA Lipid Nanoparticles . Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e139.

- 53.

Gao, M; Zhong, J; Liu, X; et al. Deciphering the Role of PEGylation on the Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated mRNA Delivery to the Liver . ACS Nano 2025, 19, 5966– 5978.

- 54.

Zhang, L; Seow, B.Y.L; Bae, K.H; et al. Role of PEGylated lipid in lipid nanoparticle formulation for in vitro and in vivo delivery of mRNA vaccines . J. Control. Release 2025, 380, 108– 124.

- 55.

Paunovska, K; Gil, C.J; Lokugamage, M.P; et al. Analyzing 2000 in vivo Drug Delivery Data Points Reveals Cholesterol Structure Impacts Nanoparticle Delivery . ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8341– 8349.

- 56.

Lokugamage, M.P; Sago, C.D; Gan, Z; et al. Constrained Nanoparticles Deliver siRNA and sgRNA to T Cells In vivo without Targeting Ligands . Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1902251.

- 57.

Zhao, X; Chen, J; Qiu, M; et al. Imidazole-Based Synthetic Lipidoids for In vivo mRNA Delivery into Primary T Lymphocytes . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20083– 20089.

- 58.

Chen, J; Ye, Z; Huang, C; et al. Lipid nanoparticle-mediated lymph node-targeting delivery of mRNA cancer vaccine elicits robust CD8 + T cell response . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207841119.

- 59.

Cheng, Q; Wei, T; Farbiak, L; et al. Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing . Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 313– 320.

- 60.

Su, K; Shi, L; Sheng, T; et al. Reformulating lipid nanoparticles for organ-targeted mRNA accumulation and translation . Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5659.

- 61.

Wilhelm, S; Tavares, A.J; Dai, Q; et al. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours . Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16014.

- 62.

Ouyang, B; Poon, W; Zhang, Y.N; et al. The dose threshold for nanoparticle tumour delivery . Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1362– 1371.

- 63.

Jia, G; Han, Y; An, Y; et al. NRP-1 targeted and cargo-loaded exosomes facilitate simultaneous imaging and therapy of glioma in vitro and in vivo . Biomaterials 2018, 178, 302– 316.

- 64.

Pham, T.C; Jayasinghe, M.K; Pham, T.T; et al. Covalent conjugation of extracellular vesicles with peptides and nanobodies for targeted therapeutic delivery . J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12057.

- 65.

Nobs, L; Buchegger, F; Gurny, R; et al. Current methods for attaching targeting ligands to liposomes and nanoparticles . J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 1980– 1992.

- 66.

Rosenblum, D; Gutkin, A; Kedmi, R; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing using targeted lipid nanoparticles for cancer therapy . Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc9450.

- 67.

Veiga, N; Goldsmith, M; Granot, Y; et al. Cell specific delivery of modified mRNA expressing therapeutic proteins to leukocytes . Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4493.

- 68.

Yang, J; Li, Y; Jiang, S; et al. Engineered brain-targeting exosome for reprogramming immunosuppressive microenvironment of glioblastoma . Exploration 2025, 5, 20240039.

- 69.

Longatti, A; Schindler, C; Collinson, A; et al. High affinity single-chain variable fragments are specific and versatile targeting motifs for extracellular vesicles . Nanoscale 2018, 10, 14230– 14244.

- 70.

Wang, Y; Wang, Z; Qian, Y; et al. Synergetic estrogen receptor-targeting liposome nanocarriers with anti-phagocytic properties for enhanced tumor theranostics . J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 1056– 1063.

- 71.

Li, Y; Gao, Y; Gong, C; et al. A33 antibody-functionalized exosomes for targeted delivery of doxorubicin against colorectal cancer . Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1973– 1985.

- 72.

Martinelli, E; De Palma, R; Orditura, M; et al. Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy . Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 158, 1– 9.

- 73.

Wicki, A; Rochlitz, C; Orleth, A; et al. Targeting tumor-associated endothelial cells: Anti-VEGFR2 immunoliposomes mediate tumor vessel disruption and inhibit tumor growth . Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 454– 464.

- 74.

Hayward, S.L; Wilson, C.L; Kidambi, S; Hyaluronic acid-conjugated liposome nanoparticles for targeted delivery to CD44 overexpressing glioblastoma cells . Oncotarget 2016, 7, 34158– 34171.

- 75.

Ramishetti, S; Kedmi, R; Goldsmith, M; et al. Systemic Gene Silencing in Primary T Lymphocytes Using Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles . ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6706– 6716.

- 76.

Tombácz, I; Laczkó, D; Shahnawaz, H; et al. Highly efficient CD4+ T cell targeting and genetic recombination using engineered CD4+ cell-homing mRNA-LNPs . Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 3293– 3304.

- 77.

Kheirolomoom, A; Kare, A.J; Ingham, E.S; et al. In situ T-cell transfection by anti-CD3-conjugated lipid nanoparticles leads to T-cell activation, migration, and phenotypic shift . Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121339.

- 78.

Xu, R; Yu, Z.L; Liu, X.C; et al. Aptamer-Assisted Traceless Isolation of PD-L1-Positive Small Extracellular Vesicles for Dissecting Their Subpopulation Signature and Function . Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1016– 1026.

- 79.

Hamula, C.L.A; Zhang, H; Guan, L.L; et al. Selection of aptamers against live bacterial cells . Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 7812– 7819.

- 80.

Kohlberger, M; Gadermaier, G; SELEX: Critical factors and optimization strategies for successful aptamer selection . Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 1771– 1792.

- 81.

Jayasena, S.D. Aptamers: An Emerging Class of Molecules That Rival Antibodies in Diagnostics . Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 1628– 1650.

- 82.

Proske, D; Blank, M; Buhmann, R; et al. Aptamers—Basic research, drug development, and clinical applications . Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 69, 367– 374.

- 83.

Mullard, A. FDA approves second RNA aptamer . Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 774.

- 84.

Xiang, D; Zheng, C; Zhou, S.F; et al. Superior Performance of Aptamer in Tumor Penetration over Antibody: Implication of Aptamer-Based Theranostics in Solid Tumors . Theranostics 2015, 5, 1083– 1097.

- 85.

Zhou, J; Rossi, J; Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: Current potential and challenges . Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 181– 202.

- 86.

Shigdar, S; Schrand, B; Giangrande, P.H; et al. Aptamers: Cutting edge of cancer therapies . Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2396– 2411.

- 87.

Esposito, C.L; Quintavalle, C; Ingenito, F; et al. Identification of a novel RNA aptamer that selectively targets breast cancer exosomes . Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 23, 982– 994.

- 88.

Wu, T; Liu, Y; Cao, Y; et al. Engineering Macrophage Exosome Disguised Biodegradable Nanoplatform for Enhanced Sonodynamic Therapy of Glioblastoma . Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2110364.

- 89.

Huynh, E; Zheng, G; Cancer nanomedicine: Addressing the dark side of the enhanced permeability and retention effect . Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 1993– 1995.

- 90.

Hedhli, J; Czerwinski, A; Schuelke, M; et al. Synthesis, Chemical Characterization and Multiscale Biological Evaluation of a Dimeric-cRGD Peptide for Targeted Imaging of αVβ3 Integrin Activity . Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3185.

- 91.

Zuo, H. iRGD: A Promising Peptide for Cancer Imaging and a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Various Cancers . J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 9367845.

- 92.

Guan, J; Guo, H; Tang, T; et al. iRGD-Liposomes Enhance Tumor Delivery and Therapeutic Efficacy of Antisense Oligonucleotide Drugs against Primary Prostate Cancer and Bone Metastasis . Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100478.

- 93.

Paunovska, K; Sago, C.D; Monaco, C.M; et al. A Direct Comparison of in vitro and in vivo Nucleic Acid Delivery Mediated by Hundreds of Nanoparticles Reveals a Weak Correlation . Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 2148– 2157.

- 94.

Lee, Y; Jeong, M; Park, J; et al. Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics . Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2085– 2096.

- 95.

Nilsson, L; Csuth, Á; Storsaeter, J; et al. Vaccine allergy: Evidence to consider for COVID-19 vaccines . Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 21, 401– 409.

- 96.

Toussirot, É; Bereau, M; Vaccination and Induction of Autoimmune Diseases . Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2015, 14, 94– 98.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.