Acute cardiac diseases, such as Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) and Acute Heart Failure (AHF), are significant global health concerns, contributing to high morbidity and mortality rates. AMI occurs due to reduced or blocked blood flow to the myocardium and is categorized into several types depending on underlying causes and clinical presentation. The pathological mechanisms involve interactions between atherosclerosis, thrombus formation, and ischemic cascades leading to myocardial cell death. AHF, characterized by the sudden worsening of heart failure symptoms, involves left ventricular dysfunction, fluid retention, and redistribution. Pharmacological interventions for AMI include immediate reperfusion, antithrombotic therapies, and long-term management with antiplatelets, anticoagulants, and vasodilators. AHF management primarily involves diuretics, inotropes, and vasodilators. This review article provides the pathological mechanisms, current pharmacological interventions for AMI and AHF, and future directions in their management.

- Open Access

- Review

Exploring Pathological Mechanisms and Pharmacological Interventions in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Acute Heart Failure

- Gaurang Shah,

- Anil Kumar Prajapati *

Author Information

Received: 15 Jan 2025 | Revised: 08 Apr 2025 | Accepted: 19 Apr 2025 | Published: 19 Nov 2025

Abstract

Keywords

acute cardiac diseases | acute myocardial infarction | acute heart failure | ACD | AMI | AHF

1.Introduction

Acute cardiac diseases (ACD) encompass a spectrum of conditions that result in sudden and severe impairment of the heart’s function, potentially leading to significant morbidity and mortality. These conditions include Acute Heart Failure (AHF) and Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI). The pathological mechanisms underlying these acute cardiac events are complex and multifaceted, involving intricate interactions between cellular, molecular, and systemic factors. Acute cardiac diseases, including AHF and AMI, are the primary causes of death and morbidity worldwide. They account for 30% of all global fatalities, resulting in 17.9 million deaths annually and comprising one-third of total world deaths, according to the World Health Organization [1]. Heart attacks contribute to over 80% of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)-related deaths, which exceed 17 million annually. Currently, India carries the highest burden of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) and myocardial infarction, with a reported increase of 138% [2]. This statistic underscores CVD as the foremost risk factor for death globally, causing over 17 million deaths each year. Women are more significantly affected than men, with a fatality ratio of 51% to 42%, and mortality rates increase with age [3]. Research also suggests that by 2025, the global number of premature deaths due to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) could reach over five million in men and 2.8 million in women [4]. In the United States, more than half the population is affected by CVD, with one person dying from the disease every 36 s, leading to approximately 659,000 deaths annually [5]. Projections indicate that by 2030, CVD will cause 23.6 million deaths. Over 75% of CVD-related mortality occurs in developing countries, with 82% of these in low- and middle-income nations. South Asian countries, including India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, have the highest incidence of CVD. In developed countries, myocardial infarction prevalence is higher in individuals over 75 years old compared to those under 45. Conversely, in South Asian countries, the highest prevalence is in individuals under 45 compared to those over 60. Myocardial infarction is about three times more commonly seen in males than in females. As per the Global Burden of Disease survey, the age-standardized CVD mortality rate in India is 272 per 100,000 people, which is higher than the global average of 235 per 100,000 people [6–9].

2.Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI)

The term Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) should be applied when there is evidence of acute myocardial injury accompanied by clinical signs of myocardial ischemia, along with a detectable rise and/or fall in cardiac biomarker levels (cardiac troponin), with at least one value exceeding the 99th percentile Upper Reference Limit (URL), and at least one of the following criteria is met:

⋅ Presence of symptoms indicative of myocardial ischemia

⋅ New ischemic changes observed on an ECG

⋅ Emergence of pathological Q waves

⋅ Imaging confirmation of new loss of viable heart muscle or new regional wall motion abnormalities consistent with an ischemic cause

⋅ Detection of a coronary artery thrombus via angiography or at autopsy [10]

MI classification is summarized in Table 1 [11–13].

Classification of Myocardial infarction.

| MI Type | Cause | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 MI | Atherothrombotic Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | Triggered by rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque |

| Type 2 MI | Imbalance between oxygen supply and demand | Ischemic myocardial injury without plaque rupture |

| Type 3 MI | Presumed acute ischemia without biomarker confirmation | Sudden death with signs of ischemia (e.g., new ischemic ECG changes or ventricular fibrillation) before biomarkers can be detected |

| Type 4a MI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) | MI was directly caused by the PCI procedure |

| Type 4b MI | Stent or scaffold thrombosis | Detected via angiography or postmortem |

| Type 4c MI | Restenosis following PCI | Narrowing of the artery again after previous treatment |

| Type 5 MI | Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) | MI associated with surgical revascularization |

Myocardial infarction is divided into two types depending on ECG: NSTEMI and STEMI. STEMI (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) or heart attack is caused by complete and persistent blood vessel obstruction, whereas NSTEMI (Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) indicates incomplete or intermittent blood vessel obstruction. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the primary cause of death worldwide, with myocardial infarction playing a major role.

2.1.Pathological Mechanism of AMI

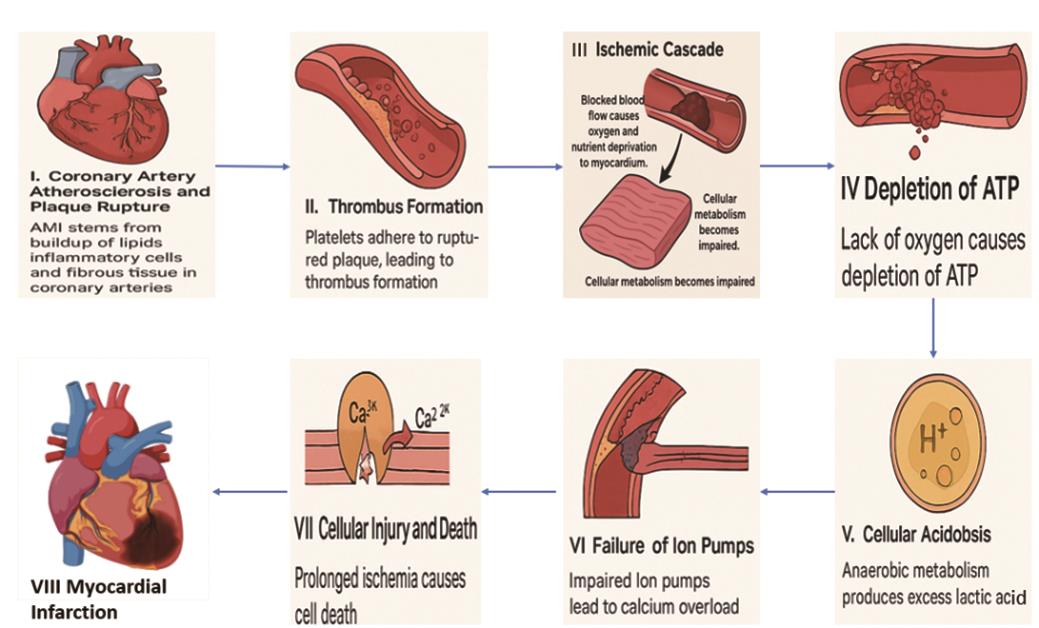

AMI, generally referred to as a heart attack, occurs due to the sudden obstruction of a coronary artery and usually occurs after the breakdown of an atherosclerotic plaque. This initiates a complex series of pathological events that lead to the death of myocardial cells and potentially irreversible injury to the heart muscle. The mechanisms are the following and are shown in Figure 1.

I. Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis and Plaque Rupture: AMI primarily stems from the progressive buildup of lipids, inflammatory cells, and fibrous tissue in coronary arteries, forming plaques. These plaques can be destabilized due to factors like elevated low-density lipoproteins (LDL), oxidative stress, and inflammation. The rupture of these unstable plaques exposes their contents to the bloodstream, triggering thrombus formation [14].

II. Thrombus Formation: Plaque rupture sets off a cascade where platelets adhere to exposed collagen in the arterial wall, releasing pro-inflammatory substances that enhance thrombus growth. The resulting thrombus can moderately or fully block the coronary artery, leading to ischemia beyond the blockage [15–17].

III. Ischemic Cascade: The cessation or reduction of blood flow to the heart muscle deprives it of oxygen and essential nutrients, severely impairing cellular metabolism.

IV. Depletion of ATP: Cardiomyocytes, lacking oxygen, cannot produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in energy depletion [18].

V. Cellular Acidosis: Anaerobic metabolism leads to lactic acid buildup, causing intracellular acidosis that further compromises cellular function [19].

VI. Failure of Ion Pumps: ATP depletion disrupts ion pump activity, particularly the Na+/K+ ATPase pump, causing intracellular calcium overload and subsequent cellular damage.

VII. Cellular Injury and Death: Prolonged ischemia leads to irreversible damage and death of cells through apoptotic (programmed cell death) and necrotic pathways. Early energy depletion triggers apoptotic pathways, while severe ischemia induces necrosis, characterized by cell swelling and rupture, causing extensive myocardial damage [20].

2.2.Pharmacological Interventions

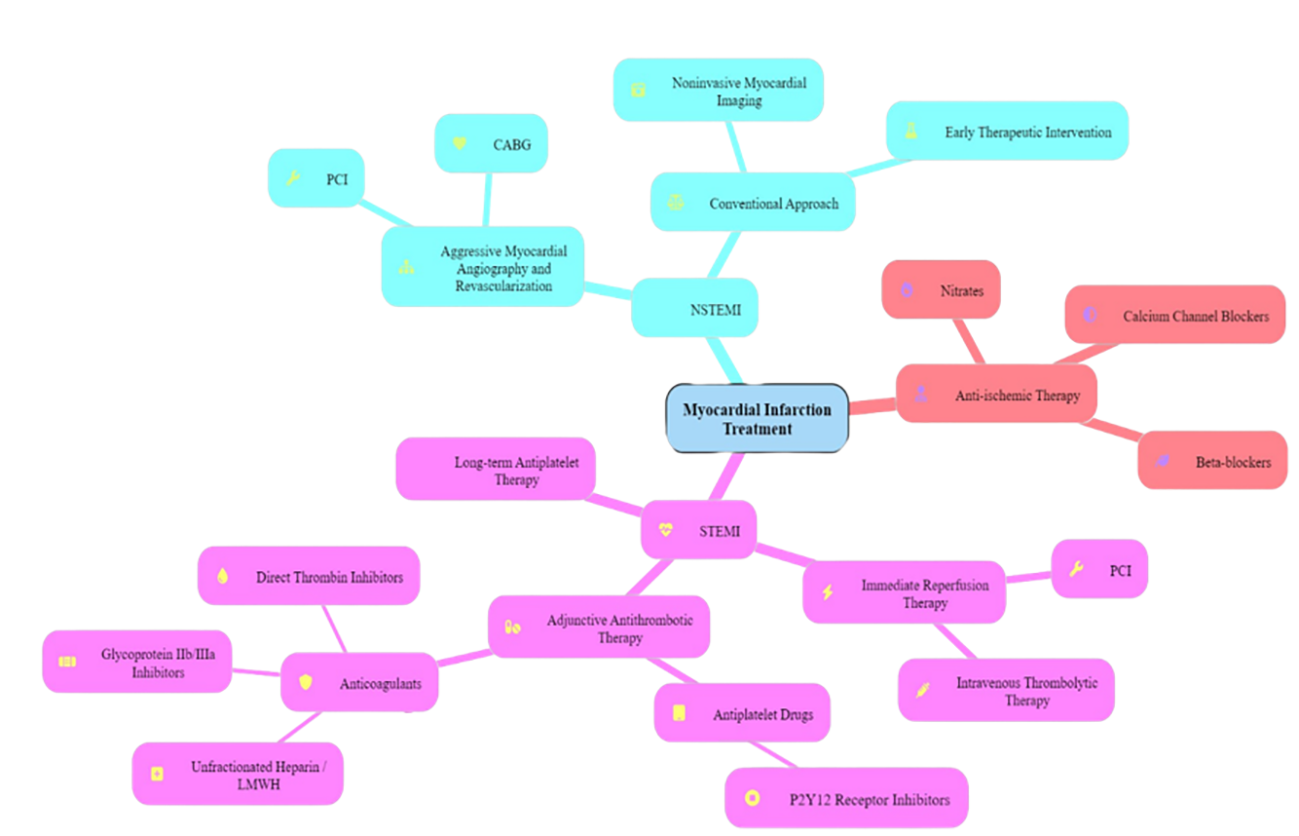

The main treatment goals for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are to provide rapid reperfusion therapy, stabilize the acute coronary lesion, address any remaining ischemia, consider revascularization, and implement long-term secondary prevention measures. Reperfusion in STEMI is achieved through either percutaneous coronary intervention or intravenous thrombolytic therapy. Adjunctive antithrombotic therapy involves the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs (Table 2 and Figure 2). These medications help prevent additional thrombosis and enable the body’s natural fibrinolytic processes to break down the existing clot. Long-term antiplatelet therapy is essential to lower the risk of recurrent thrombosis and to prevent the progression to full coronary artery blockage. For NSTEMI, Treatment strategies usually involve an initial aggressive strategy, including myocardial angiography and revascularization via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Alternatively, a conventional strategy with initial therapeutic intervention and noninvasive myocardial imaging may be used. In STEMI as well as NSTEMI, anti-ischemic therapy primarily involves the use of beta-blockers and nitrates to reduce myocardial oxygen demand. Calcium channel blockers are prescribed if symptoms persist or recur despite full-dose treatment with nitrates and beta-blockers [6].

Pharmacological therapy of AMI.

| Drug Class | Drug Name | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelet | ||

| Cyclooxygenase inhibitor | Aspirin | Aspirin permanently blocks cyclooxygenase-1 in platelets and stops the production of thromboxane A2 (TXA2), a potent vasoconstrictor and stimulator of platelet aggregation. |

| Thienopyridine derivatives | Clopidogrel, Ticlopidine, and Prasugrel | Thienopyridine derivatives are processed in the liver, where they are converted into active metabolites that permanently bind to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptors on platelets, leading to a substantial decrease in platelet activation. |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockers | Abciximab, Eptifibatide and Tirofiban | These drugs disrupt platelet cross-linking and thrombus formation, serving as potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation. |

| Anticoagulants | ||

| Unfractionated Heparin | Heparin | Heparin boosts the function of the enzyme inhibitor antithrombin III, inhibiting the development of new clots and stopping the growth of existing clots within blood vessels. It also helps prevent the re-accumulation of clots following spontaneous fibrinolysis. |

| Low molecular weight heparin | Enoxaparin and Dalteparin | These drugs exert their anti-thrombotic effect by binding to antithrombin III. This activation blocks coagulation factors Xa and IIa (thrombin), and by inhibiting thrombin, it stops the synthesis of fibrin clots. |

| Direct thrombin blockers | Dabigatran, Argatroban, and Bivalirudin | Direct thrombin blockers prevent the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin by inhibiting thrombin. |

| Nitro-Vasodilators | ||

| Nitrates | Nitroglycerin | Nitroglycerin triggers guanylate cyclase, leading to the increased production of intracellular cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP). This process causes vasodilation through the relaxation of smooth muscle cells, thereby increasing blood flow to the myocardium. Additionally, vasodilation reduces myocardial preload and cardiac wall stress. |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | ||

| Selective Beta-1 Blocker | Metoprolol, Esmolol and Atenolol | Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists inhibit the adrenergic beta receptor. In treating myocardial infarction, these medications help relieve myocardial ischemia by lowering the heart’s oxygen demand. They do so by reducing heart rate, myocardial contractility, and blood pressure, which in turn eases ischemic chest pain. |

| Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors | ||

| ACE Inhibitors | Captopril, Lisinopril and Enalapril | These agents prevent the transformation of angiotensin I into angiotensin II, leading to decreased secretion from the adrenal cortex and subsequently inhibiting the release of aldosterone. |

| Angiotensin-II Receptor Blockers (ARB) | ||

| ARB | Telmisartan, Losartan and Valsartan | These drugs block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. This results in vasodilation, decreased vasopressin secretion, and decreased formation and release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex. |

| Thrombolytics/Fibrinolytic | ||

| Thrombolytics | Urokinase, Streptokinase, Reteplase, and Alteplase | These medications convert plasminogen into plasmin, an enzyme that breaks down fibrin, the key protein in blood clot formation. By dissolving fibrin, thrombolytics help eliminate clots and reestablish blood flow to the affected region. |

Opioids: Opioids like morphine and fentanyl are powerful analgesics recommended for alleviating ischemic chest pain. Oxygen: Routine oxygen supplementation is not advised for patients who are not experiencing hypoxia.

3.Acute Heart Failure

AHF is defined as the sudden development or worsening of heart failure symptoms, necessitating medical intervention and typically resulting in hospitalization of the patient [21]. In 2005, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) described AHF as the sudden development of symptoms and signs resulting from abnormal heart function, which may arise with or without a pre-existing heart condition [22]. In their 2012 guidelines, the ESC revised this definition to describe heart failure as an abnormality in the morphology or physiology of the heart, leading to its inability to supply oxygen at a rate adequate to meet the body’s metabolic demands, even when normal filling pressures are maintained [23]. As outlined in the 2013 Practice Guideline by the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA), heart failure is characterized as a multifaceted clinical condition resulting from any impairment in the filling or pumping function of the heart’s ventricles [24,25]. Patients who present with AHF typically have an average age of 70 to 73 years, with about 50% being male. A large proportion, ranging from 65 to 75%, has a prior history of heart failure. Upon presentation, most patients show normal or high blood pressure, while those with low blood pressure make up less than 8%, and those experiencing cardiogenic shock account for fewer than 1–2% [26]. Patients with AHF often have multiple comorbid conditions, which can be broadly categorized as non-cardiovascular and cardiovascular. The cardiovascular history often includes arterial hypertension, affecting about 70% of patients, coronary artery disease (50–60%), and atrial fibrillation (30–40%) [27,28]. Non-cardiovascular comorbidities are common and include diabetes mellitus (around 40%), kidney failure affects 20–30% of patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is present in 20–30%, and anemia is seen in 15–30% [26,29,30].

3.1.Pathological Mechanism of AHF

Acute heart failure (AHF) is complex and heterogeneous, largely influenced by the nature of the underlying cardiac disease. Key mechanisms include left ventricular (LV) impairment in both systolic and diastolic function, fluid retention, and fluid redistribution.

3.1.1.LV Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunction

Acute heart failure commonly arises from a sudden deterioration in cardiac function, mainly due to the exacerbation of left ventricular diastolic function. This results in elevated left ventricular filling pressures and pulmonary congestion [31]. Acute myocardial ischemia is a common cause of such changes. Left ventricular (LV) contraction relies heavily on oxidative energy production. When ischemia occurs, it disrupts systolic function, leading to increased remaining left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume and filling pressure. Left Ventricular filling happens in two stages: the initial quick stage, which depends on quick myocardial relaxation, and a subsequent stage, which relies on left atrial contraction and the pressure gradient between the atrium and ventricle. Myocardial relaxation, which requires energy, involves the removal of cytoplasmic calcium primarily through the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pump and, to a lesser extent, through expulsion across the cardiomyocyte’s plasma membrane. The characteristics at the end of diastole of the left ventricle (LV) are influenced by factors such as residual LV end-diastolic volume and structural changes like delayed relaxation and fibrosis. Acute ischemia significantly reduces oxidative ATP production in cardiomyocytes, impairing myocardial relaxation and early LV filling, which raises filling pressures. Pre-existing conditions that affect relaxation or increase end-diastolic LV stiffness heighten the risk of acute heart failure (AHF). Atrial fibrillation can also impair LV filling by eliminating atrial contraction, significantly raising filling pressures in cases with preexisting diastolic dysfunction. For instance, severe mitral stenosis, often due to rheumatic heart disease, indicates diastolic dysfunction resulting from valve abnormalities rather than structural disease of the left ventricle (LV). Such valve issues can lead to atrial fibrillation, which further elevates the risk of acute heart failure (AHF) [32].

3.1.2.Fluid Retention

Fluid retention frequently arises from increased neurohormonal activation, specifically the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vasopressin system, resulting in the retention of salt and water by the kidneys. This can also be iatrogenic, such as from excessive intravenous fluid administration. Neurohormonal pathways are often activated early in the disease progression in chronic HF patients or those with kidney disease, making these patients particularly susceptible to fluid deposition [33].

3.1.3.Fluid Redistribution

Adrenergic activation can cause temporary vasoconstriction, resulting in a rapid shift of blood volume from the splanchnic and peripheral venous systems to the pulmonary circulation without the need for external fluid retention, a phenomenon known as fluid redistribution. Large veins normally hold about a quarter of the total blood volume, stabilizing cardiac preload and buffering fluid retention. When ventricular-vascular coupling is imbalanced, marked by heightened afterload and decreased venous capacitance, it increases preload and end-diastolic volume, which can significantly elevate cardiac workload and worsen pulmonary and systemic congestion. Furthermore, acute mechanical factors can elevate ventricular preload, playing a role in the onset of acute heart failure [34,35].

3.2.Pharmacological Interventions

3.2.1.Diuretics

The main treatment for AHF focuses on diuretics, with intravenous loop diuretics like furosemide, torsemide, or bumetanide, serving as the primary treatment for patients with AHF and fluid overload [36].

3.2.2.Digoxin

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and acute heart failure (AHF) are closely linked conditions that often coexist in various ways. AF may act as a trigger for AHF, arise as a result of it, or simply be present without directly contributing. The relationship between AF and AHF is complex due to shared underlying mechanisms, and each condition can worsen the other. Managing AF in the emergency setting when AHF is present remains a clinical challenge, influenced by the timing of onset and the severity of symptoms. Digoxin, an affordable and widely accessible cardiac glycoside, has long been recognized for its ability to enhance cardiac contractility. It also has Vago mimetic effects, slowing conduction through the atrioventricular (AV) node and helping to control heart rate. Current guidelines support its use for rate control in AF, particularly in patients who also have heart failure [36,37]. In the context of AHF—especially when AF is present or when symptoms persist despite optimized therapy—digoxin may help improve hemodynamic status and reduce the risk of hospitalization. However, it does not confer a mortality benefit [38].

3.2.3.Anticoagulants

Patients with acute heart failure (AHF) face a high risk of developing deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) due to elevated venous pressures and reduced cardiac output. Accordingly, current guidelines recommend thromboprophylaxis for hospitalized patients with acute heart failure (AHF); thromboembolic prevention using agents such as low molecular weight heparin is advised for patients with acute heart failure (AHF) who lack particular indications for anticoagulation and have no contraindications. This approach aims to lower the risk of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism [39].

3.2.4.Inotropes/Vasopressors

They support systemic perfusion and safeguard end-organ function in patients with severe systolic dysfunction, presenting with hypotension (under 90 mmHg) or diminished cardiac output, accompanied by congestion and impaired organ perfusion [40]. Phosphodiesterase type 3 (PDE3) inhibitors, such as milrinone and enoximone, are used as inotropic agents in the treatment of acute heart failure, particularly when catecholamines prove ineffective. These drugs work by increasing intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, which enhances calcium entry into cardiac cells, thereby boosting myocardial contractility and improving cardiac output [41]. Enhancing myocardial function through catecholamines and phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors inevitably raises intracellular calcium levels. However, this elevation can lead to dangerous arrhythmias and heightened energy demand by the heart. In contrast, calcium sensitizers can improve cardiac performance without increasing oxygen consumption or triggering life-threatening arrhythmias. Currently, two calcium sensitizers are available for treating heart failure in humans. Pimobendan, a positive inotrope, also suppresses the production of proinflammatory cytokines, though it significantly inhibits PDE at therapeutic doses. Levosimendan, on the other hand, enhances myocardial contractility without substantial PDE inhibition at clinically relevant concentrations [42].

3.2.5.Vasodilators

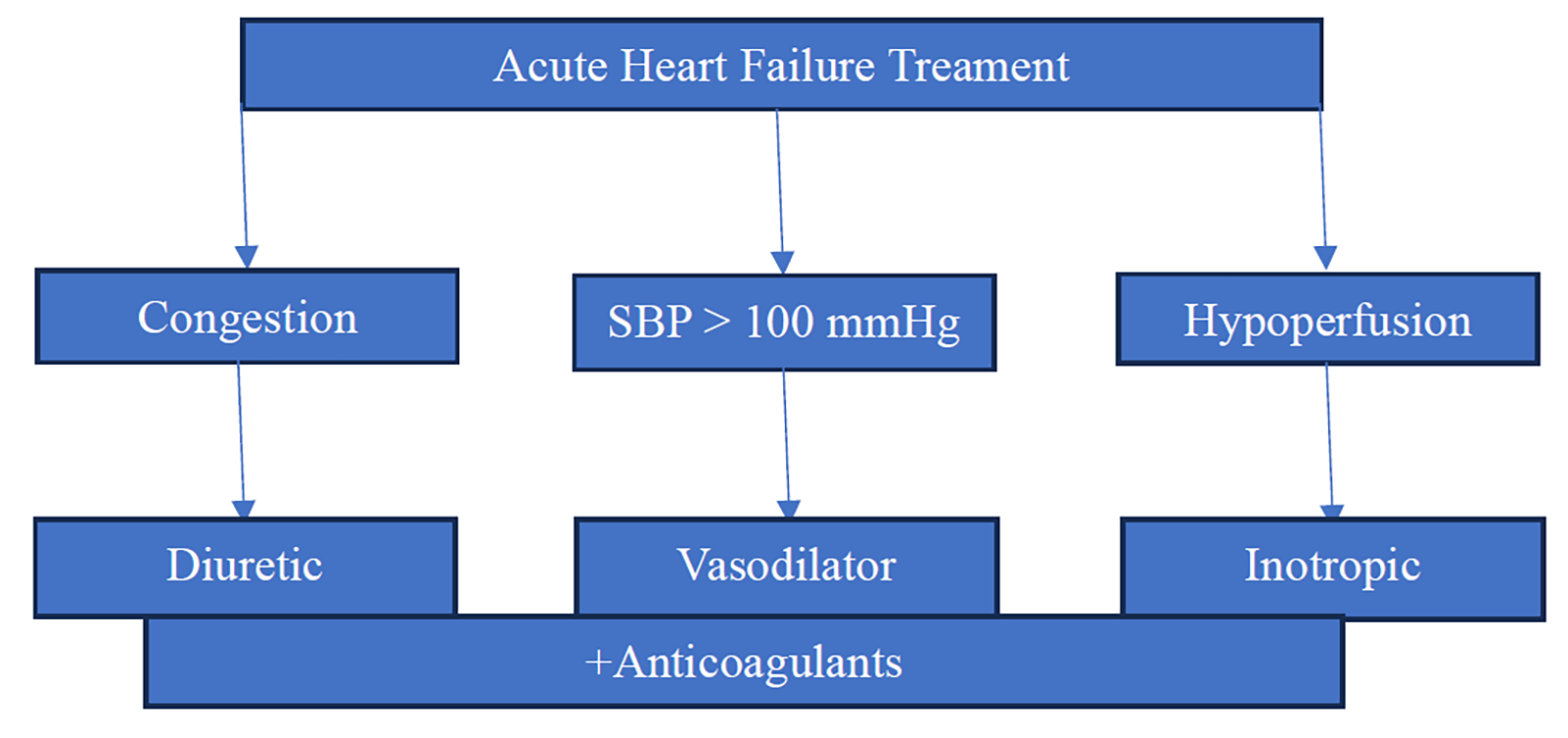

They alleviate shortness of breath in patients who do not have hypotension (systolic blood pressure > 110 mmHg) and can be helpful for those with severe congestion combined with hypertension or significant mitral valve regurgitation impacting left ventricular function. Nitrates are usually administered as a starting bolus, followed by continuous infusion. However, they should be avoided in individuals with obstructive valvular disorders, such as severe aortic stenosis, or restrictive conditions like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Figure 3 and Table 3) [43].

| Drug Class | Drug Name | Mechanism of Action | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block the Na+/K+/Cl- cotransport system in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, and also increase the excretion of Ca2+. | Allergy, dehydration, gout, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, metabolic alkalosis, nephritis, ototoxicity. | ||

| Inhibit Na+/Cl- reabsorption in the early distal convoluted tubule and reduce Ca2+ excretion. | Hypercalcemia, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hyponatremia. Sulfa allergy. | ||

| Spironolactone and eplerenone act as competitive antagonists of aldosterone receptors in the cortical collecting tubule. | Endocrine effects with spironolactone (such as antiandrogen effects and gynecomastia). Hyperkalemia (which can cause arrhythmias) | ||

| Inotropes/Vasopressors | Dobutamine | Agonists of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors, with varying effects on α receptors | Hypotension, Phlebitis, Increased myocardial oxygen demand, |

| Dopamine | Adrenergic and dopaminergic receptor agonist | Tachycardia, Arrhythmias, | |

| Milrinone | A phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor that elevates cyclic adenosine monophosphate | Hypotension, Ventricular arrhythmias, Tachycardia | |

| Norepinephrine | Strong agonist of beta1 and alpha1 receptors | Arrhythmias, End-organ hypoperfusion, Tissue necrosis | |

| Epinephrine | Complete agonist of beta receptors | ||

| Vasodilators | Promote vasodilation by boosting nitric oxide (NO) levels in vascular smooth muscle, which raises cGMP levels and induces smooth muscle relaxation, affecting veins more than arteries. | ||

| A short-acting vasodilator affects both arteries and veins equally. Increases Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP) through the direct release of nitric oxide (NO). |

4.Future Directions

Acute cardiac disease therapeutics present exciting opportunities to advance treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes. A promising direction involves the development of combination therapies, where multiple therapeutic agents are combined in a polypill to target various pathways in the pathophysiology of acute cardiac diseases, potentially enhancing treatment efficacy through synergistic effects (Table 4).

| Category | Target/Drug Class | Potential Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Platelet Inhibition Optimization | P2Y12 blockers + PAR antagonists + GP IIb/IIIa blockers | Maximize platelet inhibition and reduce thrombotic events |

| Novel Cardioprotective Targets | Acid-sensitive cardiac ion channels | Enhance cardioprotection and reduce infarct size |

| Targets Influencing Necroptosis & Inflammation | Ferritin heavy chain (FTH1), IFNGR1, STAT3, TLR4 | Modulate necroptosis and immune cell infiltration in AMI |

| Emerging Antiplatelet Targets | Glycoprotein VI (GPVI), PAR-4, Glycoprotein Ib (GPIb), 5-HT2A receptor, protein disulfide isomerase, P-selectin, PI3Kβ | Improve the efficacy of antiplatelet therapies. |

These emerging targets in acute cardiac diseases have the potential to significantly improve outcomes by addressing critical factors such as oxidative stress, inflammation, atherosclerosis, cardiac remodeling, and myocardial infarction [48]. Such advancements could also reduce the healthcare costs associated with cardiovascular diseases, paving the way for a new era of personalized and effective ACD treatments.

5.Conclusions

In conclusion, this review article presents an overview of the pathophysiology and pharmacological management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and acute heart failure (AHF). It explores future research into innovative pharmacological agents and targeted therapies that could significantly improve outcomes for patients with acute cardiac diseases, potentially reducing healthcare costs and advancing treatment approaches.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies: No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Cabral, C.E; Klein, M.R.S.T; Phytosterols in the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017, 109, 475–482. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20170158.

- 2.

Jan, B; Dar, M.I; Choudhary, B; et al. Cardiovascular Diseases Among Indian Older Adults: A Comprehensive Review. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2024, 2024, 6894693. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6894693.

- 3.

Nichols, M; Townsend, N; Scarborough, P; et al. Cardiovascular Disease in Europe 2014: Epidemiological Update. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2950–2959. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299.

- 4.

Loitongbam, L; Surin, W.R; The Rising Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Thrombosis in India: An Epidemiological Review. Cureus 2024, 16, 73786. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.73786.

- 5.

Benjamin, E.J; Blaha, M.J; Chiuve, S.E; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e146–e603. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485.

- 6.

Fathima, S.N. An Update on Myocardial Infarction. In Current Research and Trends in Medical Science and Technology; Kumar, D., Ed.; Scripown Publications: New Delhi, India, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1–33.

- 7.

Gupta, R; Mohan, I; Narula, J; Trends in Coronary Heart Disease Epidemiology in India. Ann. Glob. Health 2016, 82, 307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2016.04.002.

- 8.

Chadwick Jayaraj, J; Davatyan, K; Subramanian, S.S; et al. Epidemiology of Myocardial Infarction. In Myocardial Infarction; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.74768.

- 9.

Mendis, S. Global Progress in Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 67, S32–S38. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2017.03.06.

- 10.

Thygesen, K; Alpert, J.S; Jaffe, A.S; et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation 2018, 72, 2231–2264. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617.

- 11.

Thygesen, K; Alpert, J.S; White, H.D; Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2007, 116, 2634–2653. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397.

- 12.

Thygesen, K; Alpert, J.S; Jaffe, A.S; et al. Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2551–2567. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184.

- 13.

Thygesen, K; Alpert, J.S; Jaffe, A.S; et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 237–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462.

- 14.

Libby, P; Bornfeldt, K.E; Tall, A.R; Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 531–534. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308334.

- 15.

Ojha, N; Myocardial Infarction, A.S; Publishing, StatPearls; Island, Treasure; , 2023.

- 16.

Mechanic, O.J; Gavin, M; Grossman, S.A; Acute Myocardial Infarction; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2017.

- 17.

Ruggeri, Z.M. Platelets in Atherothrombosis. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1102-1227.

- 18.

Frangogiannis, N.G. Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction. In Comprehensive Physiology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1841–1875. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c150006.

- 19.

Halestrap, A.P; Richardson, A.P; The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition: A Current Perspective on Its Identity and Role in Ischaemia/Reperfusion Injury. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2015, 78, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.018.

- 20.

Frangogiannis, N.G. The Mechanistic Basis of Infarct Healing. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2006, 8, 1907–1939. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2006.8.1907.

- 21.

Farmakis, D; Parissis, J; Lekakis, J; et al. Acute Heart Failure: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2015, 68, 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2014.11.004.

- 22.

Nieminen, M.S; Böhm, M; Cowie, M.R; Executive Summary of the Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Heart Failure: The Task Force on Acute Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 384–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi044.

- 23.

McMurray, J.J.V; Adamopoulos, S; Anker, S.D; et al. ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in Collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1787–1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104.

- 24.

Yancy, C.W; Jessup, M; Bozkurt, B; et al. ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, e147–e239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019.

- 25.

Krüger, W. Acute Heart Failure Syndromes. In Acute Heart Failure; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 81–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54973-6_2.

- 26.

Farmakis, D; Parissis, J; Papingiotis, G; et al. Acute Heart Failure; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199687039.003.0051_update_001.

- 27.

Kim, I.-C. Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail. Clin. 2021, 17, 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2021.03.001.

- 28.

Di Palo, K.E; Barone, N.J; Hypertension and Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2020, 16, 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2019.09.001.

- 29.

Pellicori, P; Cleland, J.G.F; Clark, A.L; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2020, 16, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2019.08.003.

- 30.

Ananthram, M.G; Gottlieb, S.S; Renal Dysfunction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail. Clin. 2021, 17, 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2021.03.005.

- 31.

Arrigo, M; Parissis, J.T; Akiyama, E; et al. Understanding Acute Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Diagnosis. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2016, 18, G11–G18. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suw044.

- 32.

Shah, A.M. Ventricular Remodeling in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2013, 10, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-013-0166-4.

- 33.

Hartupee, J; Mann, D.L; Neurohormonal Activation in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.163.

- 34.

Arrigo, M; Jessup, M; Mullens, W; et al. Acute Heart Failure. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0151-7.

- 35.

Cotter, G; Metra, M; Milo-Cotter, O; et al. Fluid Overload in Acute Heart Failure — Re-distribution and Other Mechanisms beyond Fluid Accumulation. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2008, 10, 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.01.007.

- 36.

McDonagh, T.A; Metra, M; Adamo, M; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368.

- 37.

Velliou, M; Sanidas, E; Diakantonis, A; et al. The Optimal Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Acute Heart Failure in the Emergency Department. Medicina 2023, 59, 2113. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122113.

- 38.

Campbell, T.J; MacDonald, P.S; Digoxin in Heart Failure and Cardiac Arrhythmias. Med. J. Aust. 2003, 179, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05445.x.

- 39.

Siniarski, A; Gąsecka, A; Borovac, J.A; et al. Blood Coagulation Disorders in Heart Failure: From Basic Science to Clinical Perspectives. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.12.012.

- 40.

Masarone, D; Melillo, E; Gravino, R; et al. Inotropes in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2021, 17, 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2021.05.004.

- 41.

Hoffman, T.M. Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors. In Heart Failure in the Child and Young Adult; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 517–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802393-8.00040-5.

- 42.

Lehmann, A; Boldt, J; Kirchner, J; The Role of Ca++-Sensitizers for the Treatment of Heart Failure. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2003, 9, 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075198-200310000-00002.

- 43.

Carlson, M.D; Eckman, P.M; Review of Vasodilators in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The Old and the New. J. Card. Fail. 2013, 19, 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.05.007.

- 44.

Felker, G.M; Ellison, D.H; Mullens, W; et al. Diuretic Therapy for Patients with Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1178–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.059.

- 45.

Mauro, C; Chianese, S; Cocchia, R; et al. Acute Heart Failure: Diagnostic–Therapeutic Pathways and Preventive Strategies—A Real-World Clinician’s Guide. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030846.

- 46.

Mitsis, A; Myrianthefs, M; Sokratous, S; et al. Emerging Therapeutic Targets for Acute Coronary Syndromes: Novel Advancements and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081670.

- 47.

Alenazy, F.O; Thomas, M.R; Novel Antiplatelet Targets in the Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Platelets 2021, 32, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2020.1763731.

- 48.

Afzal, M. Recent Updates on Novel Therapeutic Targets of Cardiovascular Diseases. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2021, 476, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03891-8.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.