Arylsulfatase B (ARSB), also known as N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase, is a lysosomal enzyme specifically involved in the degradation of chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate. In recent years, studies have demonstrated that ARSB plays multifaceted roles in tumor extracellular matrix remodeling, signal transduction, and immune regulation. Across different cancer types, ARSB exhibits heterogeneous expression patterns and displays tumor type–dependent dual regulatory functions. Mechanistically, ARSB modulates multiple signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT, and MAPK, and influences PD-L1 expression, thereby participating in tumor proliferation, invasion, and immune evasion. This review systematically summarizes the gene structure and biological functions of ARSB, its roles across various cancer types, prognostic value based on TCGA pan-cancer data,and discusses therapeutic strategies such as enzyme replacement therapy and gene therapy, highlighting its potential as a target for personalized cancer treatment.

- Open Access

- Review

The Role and Therapeutic Potential of ARSB Gene in Tumor Development

- Zhiqiang Zhang 1,2,†,

- Qunlong Jin 1,2,†,

- LiangJin Zhang 3,†,

- Junyao Wan 3,†,

- Yunfei Gao 4,

- Ningning Li 2,5,

- Haitao Wang 6,*,

- Yulong He 1,*,

- Xin Zhong 1,2,*

Author Information

Received: 24 Apr 2025 | Revised: 05 Jun 2025 | Accepted: 10 Jun 2025 | Published: 04 Dec 2025

Abstract

Keywords

lysosomal enzyme | ARSB | tumor development | signaling pathway

1.Introduction

1.1.Current Status of Cancer

Cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease characterized by sustained proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and evasion of immune surveillance. It remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide [1]. Contemporary research has revealed that cancer initiation and progression are not solely driven by intrinsic abnormalities of tumor cells but are also profoundly influenced by the surrounding tumor microenvironment.

1.2.Composition and Function of the Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment (TME) comprises a diverse array of components, including immune cells [2], fibroblasts [3], and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [4]. These elements interact either through secreted factors or direct cellular contact to collaboratively influence cancer initiation and progression [5–7]. For instance, alterations in ECM stiffness [4], immune cell infiltration patterns [2], and metabolic reprogramming [6,8] within the TME have been shown to significantly affect tumor cell migration, proliferation, and therapeutic responsiveness [3,7]. Among these components, the ECM has recently emerged as a critical target in cancer research [9]. As a major structural and functional component of the TME, the ECM serves not only as mechanical support but also as a dynamic regulator of the microenvironment and a reservoir of signaling molecules [10]. It consists primarily of structural proteins [11], adhesive glycoproteins [12], proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) [13], and basement membrane components [14]. Through regulation of tumor cell adhesion, migration, and intracellular signaling, the ECM actively contributes to cancer progression, immune evasion, and the development of therapeutic resistance [15].

1.3.Reappraisal of Lysosomal Enzyme Function

Traditionally, lysosomes have long been regarded as the “digestive system” of the cell, primarily responsible for the degradation of macromolecules. However, recent studies have revealed that lysosomal enzymes exert far more complex functions in cancer, including roles in signal transduction [16], immune evasion [17], metabolic regulation, and cellular reprogramming [18].

Lysosomal enzymes are pivotal in ECM homeostasis. Beyond directly degrading and recycling ECM components such as collagen and GAGs, they also modulate key signaling pathways, including those involved in autophagy, and transcriptional regulation, thereby facilitating ECM remodeling [19]. Under pathological conditions, lysosomal dysfunction can lead to aberrant ECM accumulation or degradation, contributing to fibrosis, neurodegenerative disorders, and tumor progression [20]. Moreover, the exocytotic release of lysosomal enzymes plays a role in tissue repair and microenvironmental remodeling, indicating their potential involvement in tumor invasion and metastasis [21].

2.Methodology

This review was synthesized based on literature retrieved from PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), including both English and Chinese sources published between 1980 and 2024.

Search terms included:

“Arylsulfatase B”, “ARSB”, “ARSB and cancer”, “ARSB and tumor”, “ARSB and carcinoma”, “ARSB and malignancy”, “Sulfatases”, and their Chinese equivalents for CNKI.

Given the limited number of original studies on ARSB in cancer, we broadened the scope to include original research articles, reviews, and conference abstracts that provided mechanistic, clinical, or therapeutic insights related to ARSB.

After screening and evaluation, a total of 38 articles directly related to ARSB were included in this review for detailed analysis and synthesis.

3.The ARSB Gene and Its Protein

3.1.Genomic Localization and Splice Variants

ARSB, also known as N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase, is the only known enzyme capable of removing the 4-sulfate groups from dermatan sulfate (DS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) [22]. These two GAGs play essential roles in maintaining ECM integrity and lysosomal homeostasis. Their abnormal accumulation disrupts lysosomal acidification, membrane stability, and autophagic flux, particularly in the tumor microenvironment, where altered lysosomal activity can remodel the cancer cell–matrix interface and affect cell survival and invasiveness [6].

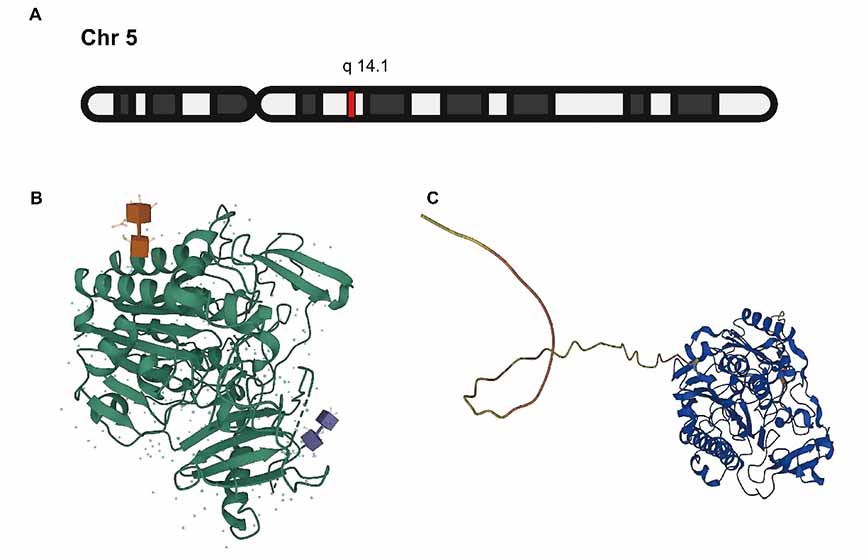

The ARSB gene is located on chromosome 5q14.1 and encodes a highly conserved lysosomal enzyme belonging to the sulfatase superfamily [23] (Figure 1). Multiple splice variants of the gene have been identified. Among them, transcript variant 1 (NM_000046.5) encodes the functional ARSB protein, consisting of 533 amino acid residues, while transcript variant 2 (NM_198709.3) encodes a 413-amino acid protein due to a 3′-end deletion [24].

3.2.Protein Structure and Catalytic Properties

The ARSB protein functions as a homodimer within the lysosome and belongs to the class of metal ion–dependent hydrolases. Its N-terminal segment (residues 1–36) constitutes a signal peptide responsible for lysosomal targeting. Notably, Cys91 undergoes post-translational modification to formylglycine, which participates in ester bond formation at the catalytic site, a crucial determinant of its enzymatic function. ARSB catalyzes the hydrolysis of the 4-sulfate groups from CS and DS, facilitating the degradation of GAGs [25].

3.3.Subcellular Localization and Biological Functions

Although ARSB is predominantly localized in the lysosome, it has also been detected on the cell membrane and in the nucleus, suggesting potential non-canonical roles in signal transduction and transcriptional regulation [26]. Alterations in ARSB expression significantly affect the sulfation patterns of the ECM, thereby modulating the binding and release of critical mediators such as galectin-3 and SHP2, with effects on cell proliferation, migration, and immune responses [22].

3.4.Mutations and Disease Associations

Loss-of-function mutations in ARSB are the primary cause of Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (MPS VI), an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder characterized by systemic accumulation of GAGs. Clinically, MPS VI manifests as skeletal abnormalities, hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary dysfunction, and cardiac valve disease [27,28]. Currently, over 160 ARSB mutations have been reported, including missense mutations, splice-site alterations, and large deletions, all of which significantly impair ARSB enzymatic activity [29–31].

4.ARSB Expression Across Human Cancers

4.1.Findings from TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis

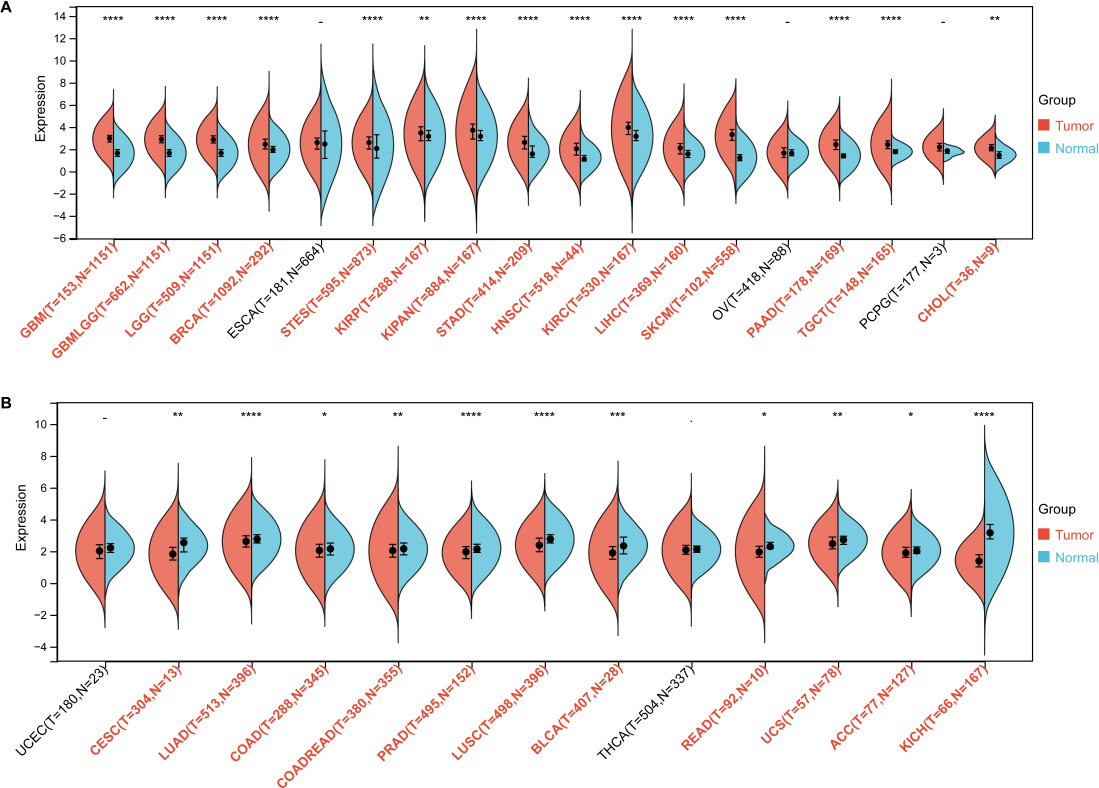

We extracted ARSB gene expression data from the standardized TCGA pan-cancer dataset in the UCSC Xena database, including both normal and tumor tissue samples. Expression values were log2(x + 1) transformed. To ensure analytical reliability, cancer types with fewer than three samples were excluded, resulting in 31 cancer types for analysis. Statistical comparisons between normal and tumor tissues were performed using R (version 3.6.4) and the unpaired Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

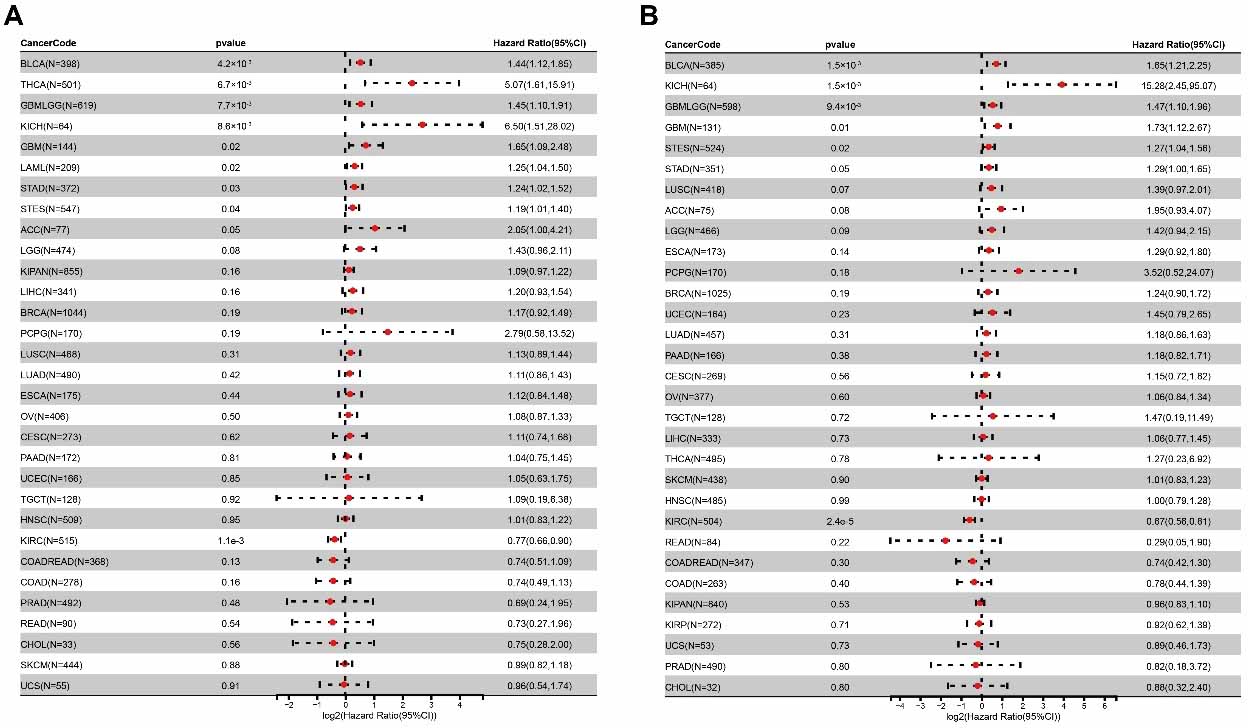

Our pan-cancer analysis revealed significant heterogeneity in ARSB expression across various tumor types and is significantly associated with both overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in multiple malignancies.

As shown (Figure 2), upregulated ARSB expression was observed in several tumors, including (Figure 2A) glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), lower grade glioma and glioblastoma (GBMLGG), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), stomach and esophageal carcinoma (STES), Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM).

In contrast, (Figure 2B) downregulation of ARSB was noted in prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), and bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA). No statistically significant differences in ARSB expression were found in esophageal carcinoma (ESCA) and thyroid carcinoma (THCA).

Survival analyses (Figure 3) demonstrated that high ARSB expression was significantly associated with poor OS and DSS in several tumor types, including GBM, GBMLGG, STAD, and STES. In contrast, low ARSB expression was correlated with poor OS and DSS in tumors such as BLCA and kidney chromophobe carcinoma (KICH).

These expression patterns suggest that ARSB does not exert a uniformly pro-tumorigenic or tumor-suppressive role across all malignancies. Instead, its regulatory effects may depend on tumor type, cellular context, and the tumor microenvironment, reflecting a complex and potentially biphasic regulatory function.

4.2.Summary of Current Research on ARSB in Cancer

ARSB exhibits differential expression across various cancer types (Table 1). Notably, MPS VI results from diverse mutations in the ARSB gene [33]—including missense, nonsense, splice-site mutations, and small deletions—that lead to absent or significantly reduced ARSB activity. In cancers where ARSB activity is diminished, although the precise cause (such as gene mutations) is not always identified, a decline in ARSB function is consistently observed.

ARSB expression and functional significance across different cancer types.

| Cancer | ARSB | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Significantly Decreased | ARSB is significantly downregulated in breast cancer cells, particularly estrogen-responsive types [34]. Functional studies suggest a tumor-suppressive role via regulation of C4S metabolism and proteoglycans such as syndecan-1 and decorin [35]. |

| Melanoma | Significantly Decreased | ARSB expression is significantly decreased in melanoma tissues and B16F10 cells. ARSB deficiency enhances cell invasiveness and MMP-2 expression, whereas treatment with exogenous recombinant ARSB suppresses tumor growth and improves survival outcomes in murine models [36,37]. |

| Prostate Cancer | Downregulated | ARSB is downregulated in prostate cancer, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and enzymatic assays, with concurrent increases in CS levels [38]. Reduced ARSB expression is significantly associated with higher Gleason scores and PSA recurrence, and serves as a prognostic biomarker superior to traditional clinical indicators [39,40]. |

| Colon Cancer | Progressively Decreased | ARSB expression and activity progressively decline from adenoma to carcinoma [26], with further reduction in invasive subtypes. Its co-expression with maspin and ARSA predicts poor prognosis [41], while ARSB silencing enhances MMP9, RhoA activation, and cell migration [42]. |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Upregulated | ARSB is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, and its circular RNA (circARSB) encodes a functional peptide, circARSB-321aa, which activates the PI3K/AKT pathway to promote cell proliferation and migration, suggesting a pro-tumorigenic role [43]. |

| Stomach Adenocarcinoma | Upregulated | ARSB is upregulated in gastric cancer tissues and correlates with TNM stage. ARSB silencing inhibits proliferation and migration, induces apoptosis, and suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling, indicating a pro-tumorigenic role [44]. |

| Lung Cancer | Significantly Upregulated | ARSB activity is significantly increased in lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. A tumor-specific ARSB isoform (B1) [45] with a unique isoelectric point (pI = 6.7) and phosphorylation was identified, suggesting potential pro-tumorigenic roles in metabolic regulation or microenvironmental adaptation [46]. |

| Thyroid Cancer | Unknown | A genome-wide association study identified a significant correlation between the ARSB SNP rs13184587 and susceptibility to differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) in an Italian population (p = 8.54 × 10-6), suggesting a potential role of the ARSB locus in DTC genetic predisposition [47]. |

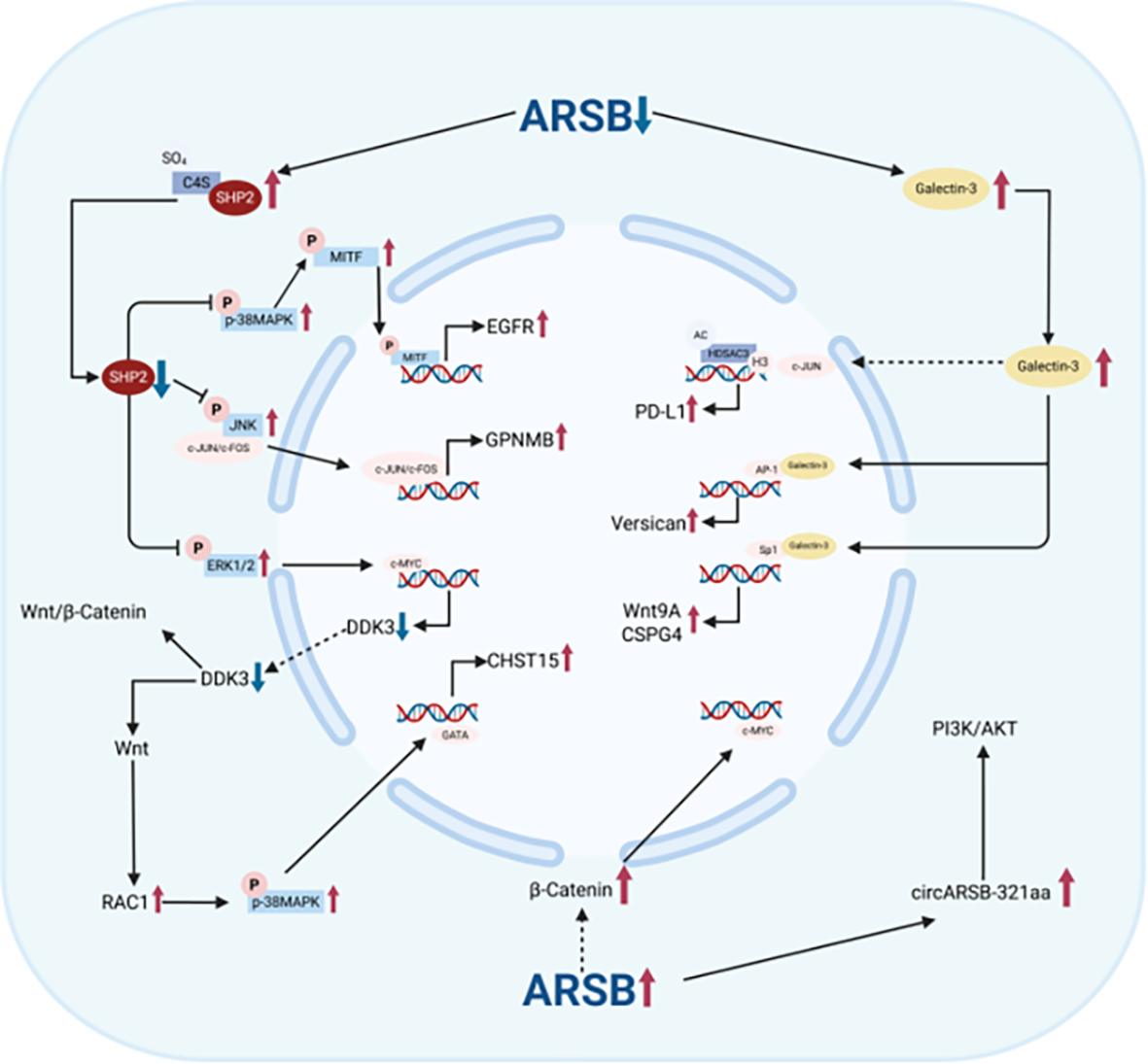

5.Mechanistic Roles of ARSB in Cancer

Recent studies have shown that ARSB influences multiple signaling pathways and regulatory axes involved in tumor initiation and progression, demonstrating complex, tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms, as summarized in the Table 2.

Mechanistic roles of ARSB in different cancer types.

| Cancer | Pathway/ Regulatory Axis | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer | C4S/SHP2/JNK/ EGFR Pathway | ARSB downregulation leads to C4S accumulation, which inhibits SHP2 activity, activates JNK signaling, promotes c-Jun nuclear translocation and EGFR upregulation, thereby enhancing EGF-induced proliferation in prostate cancer cells [48]. |

Galectin-3/AP-1/ Versican Pathway | ARSB loss increases C4S and versican expression via enhanced AP-1 activity due to reduced Galectin-3 binding [49]. In prostate cancer, low ARSB enhances versican–EGFR interaction, potentially affecting EGFR signaling [39,50,51]. | |

Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway | ARSB downregulation in prostate cancer promotes C4S accumulation, inhibits SHP2, and induces epigenetic silencing of DKK3, thereby activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling [52]. | |

| Prostate Cancer | Non-canonical Wnt/CHST15/ CSE Pathway | ARSB downregulation activates the Wnt3A/Rac1/p38 MAPK/GATA-3 axis, promoting CHST15 expression and CSE accumulation, thereby inducing EMT and enhancing invasiveness [53]. |

| Melanoma | MAPK/ERK Pathway | ARSB downregulation in melanoma inhibits SHP2 via C4S accumulation, activates p38 MAPK/MITF signaling, and upregulates GPNMB, promoting malignancy [54]. ARSB restoration reverses these effects, reduces Sp1, and suppresses MMP2/9 expression, limiting invasiveness [37]. |

HDAC3/c-Jun/ PD-L1 Regulatory Axis | ARSB loss promotes nuclear c-Jun accumulation and HDAC3-mediated H3K27 acetylation at the PD-L1 promoter, increasing PD-L1 expression. Exogenous ARSB interacts with IGF2R and suppresses PD-L1, enhancing immune cytotoxicity [55]. | |

| Stomach Adenocarcinoma | Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway | ARSB upregulates β-catenin and c-Myc to promote proliferation and migration, while its knockdown inhibits the pathway and induces apoptosis [44]. |

| Colon Cancer | BMP4/Wnt9A/CHST11 Pathway | ARSB downregulation increases C4S sulfation, which traps BMP4 at the membrane and reduces Smad3 phosphorylation and CHST11 expression. Meanwhile, reduced Galectin-3 binding promotes Wnt9A upregulation via Sp1, which further suppresses CHST11. This bidirectional regulation may alter glycosylation and progression in colorectal cancer [56]. |

| Maspin/ARSB Regulatory Axis | ARSB downregulation with increased maspin is linked to greater invasion and lymphatic metastasis, suggesting a cooperative role in immune evasion and tumor progression [57]. | |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | PI3K/AKT Pathway | circARSB encodes the oncogenic peptide circARSB-321aa, which activates PI3K/AKT signaling to promote proliferation and migration, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target and prognostic marker [43]. |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Warburg Effect | ARSB loss promotes the Warburg effect by reducing oxygen consumption and increasing lactate production, disrupting redox balance even under normoxia [58]. |

The decline in ARSB activity promotes cancer progression primarily through decreased SHP2 activity and increased Galectin-3 levels. In addition, cancers with elevated ARSB activity are mainly associated with the activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (Figure 4).

6.Therapeutic Implications of ARSB in Cancer

Aberrant expression and function of ARSB in various cancers highlight its potential as a valuable therapeutic target. Drawing on its well-established role in the treatment of genetic disorders, particularly MPS VI, current evidence suggests that ARSB-targeted cancer therapy may be explored on three major fronts.

6.1.Insights from ARSB-Deficiency Therapies into Cancer Intervention

As the causative gene for MPS VI, ARSB has been the focus of extensive therapeutic research. Its clinical management provides a foundational reference for translational approaches in oncology.

6.1.1.Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT)

ERT using recombinant human ARSB (galsulfase) has been shown to significantly improve tissue damage and functional impairment in MPS VI patients [27]. However, long-term ERT can induce anti-ARSB antibodies, potentially diminishing therapeutic efficacy. This underscores the need to consider immunogenicity mitigation strategies—such as PEGylation, antibody screening, or adjuvant modulation—if ARSB-based ERT is to be repurposed for cancer treatment.

6.1.2.Long-Term Replacement Potential of Gene Therapy

Gene therapy offers a promising strategy for sustained correction or regulation of pathogenic genes, enabling targeted and durable interventions in complex diseases such as cancer. Its advantages include high specificity, long-term efficacy, and applicability to various treatment-resistant malignancies [63,64]. A 2024 study reported that liver-targeted AAV8.TBG.hARSB achieved stable expression of ARSB enzyme activity for over three years in MPS VI patients—reaching 38–67% of normal levels—without serious adverse events [30]. This approach suggests the feasibility of localized and controllable ARSB restoration in cancer, particularly for focal tumors with ARSB downregulation, such as melanoma and prostate cancer.

6.1.3.Metabolic Reprogramming and Microenvironmental Modulation

ARSB enzymatic activity is oxygen-dependent, and its deficiency has been shown to induce metabolic reprogramming and promote the Warburg effect [58]. This suggests ARSB may serve as a regulator of oxidative metabolism in metabolically active tumors. Restoration of ARSB expression may help re-establish metabolic balance within the tumor microenvironment, potentially enhancing the efficacy of other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy.

6.2.Replacement Strategies for ARSB-Deficient Cancers

In cancers such as melanoma, prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer, ARSB is frequently downregulated, leading to C4S accumulation, SHP2 inactivation, dysregulation of MAPK and JNK signaling, and activation of immune evasion pathways [36,48,55]. Exogenous recombinant ARSB has been shown to suppress tumor progression and prolong survival in preclinical models [37]. Drawing from MPS VI treatment experience, several considerations are essential for ARSB replacement in cancer. Localized delivery: Higher intratumoral concentrations are required than in systemic deficiency, possibly achievable via nanocarriers or IGF2R-targeted systems [55,65] elicit anti-ARSB antibodies, necessitating immune tolerance strategies [66]. Combination therapies: ARSB restoration may enhance sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors [67], and be synergistic with metabolic modulators or anti-angiogenic agents [68].

6.3.ARSB Inhibition Strategies for Cancers with High ARSB Expression

In gastric and liver cancers, high ARSB expression is associated with activation of Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/AKT pathways, promoting proliferation, migration, and treatment resistance [43,44]. Thus, ARSB may serve as an upstream target for growth inhibition and signaling reprogramming.

Future ARSB inhibitors for cancer should be highly specific, low-molecular-weight, and stable, referencing steroid sulfatase inhibitor development [69]. Local delivery is preferred to limit off-target effects and immunogenicity [70], and combination therapy may enhance Wnt or PI3K/AKT blockade.

Given the role of the tumor stroma in progression and resistance [71], and the ability of ARSB to induce EMT [53], combining ARSB inhibition with anti-stromal strategies may further improve outcomes [72].

7.Review and Outlook on ARSB in Cancer

Several reviews have discussed the role of ARSB in disease pathogenesis and its potential as a therapeutic target [22,73]. While existing literature has explored its biological functions in metabolic disorders and selected cancers, systematic analyses are still lacking. Key gaps include: (1) mechanistic studies of its context-dependent dual roles—oncogenic in gastric cancer vs. tumor-suppressive in prostate cancer [40]; (2) integrated bioinformatic reviews utilizing datasets such as TCGA to define expression profiles, prognostic value, and regulatory networks.

However, current findings on ARSB expression remain inconsistent across studies. These discrepancies likely stem from tumor-specific biology—such as microenvironmental differences and glycosaminoglycan composition—as well as methodological variations. For example, some studies assess mRNA only, while others evaluate protein levels or enzymatic activity via IHC, western blot, or activity assays. Antibody specificity, sample preservation, and detection thresholds further complicate interpretation. Older studies [45,46] also lacked clear distinction between ARSB and ARSA, possibly contributing to misidentification.

This review builds upon current knowledge by combining bioinformatics and experimental validation, offering a comprehensive summary of ARSB’s roles and therapeutic implications across cancer types, along with challenges in clinical translation. Reviews on the sulfatase family also highlight ARSB’s broader biological relevance beyond MPS VI, including tumor suppression and signaling regulation [22].

In summary, ARSB plays a complex, tumor-specific role in cancer development by modulating GAGs sulfation, thereby influencing signaling, the tumor microenvironment, and immune response. Therapeutic strategies targeting ARSB—via gene therapy, enzyme restoration, or inhibition—show promise, especially in ARSB-deficient tumors. Preclinical melanoma models demonstrate that recombinant ARSB exerts antitumor effects [69], supporting its translational potential.

Future research should focus on cancer-type–specific functions of ARSB, standardization of detection protocols, and further preclinical validation across broader malignancies. Clinical trials evaluating ARSB-targeted therapies—starting with galsulfase in cancers with strong preclinical evidence—are essential to determine safety and efficacy. Development of specific ARSB inhibitors may also benefit cancers with ARSB overexpression. Continued investigation into ARSB biology will likely contribute to the advancement of novel and effective cancer therapies.

Author Contributions: Z.Z.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, software; Q.J.: writing—review and editing, data curation, investigation; L.Z.: writing—review and editing, data curation, investigation; J.W.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, investigation; Y.G.: writing—review and editing, investigation, resources; N.L.: writing—review and editing, methodology, validation; H.W.: writing—review and editing, supervision, validation; Y.H.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, supervision, project administration, resources; X.Z.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, supervision, project administration, resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies: No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

Abbreviations

| ACC | Adrenocortical carcinoma | KIRP | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein-1 | LAML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| ARSB | N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase | LGG | Brain Lower Grade Glioma |

| BLCA | Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma | LIHC | Liver hepatocellular carcinoma |

| BMP4 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 | LUAD | Lung adenocarcinoma |

| BRCA | Breast invasive carcinoma | LUSC | Lung squamous cell carcinoma |

| C4S | chondroitin 4-sulfate | MESO | Mesothelioma |

| CESC | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma | MITF | microphthalmia-associated transcription factor |

| CHOL | Cholangiocarcinoma | MMP-2 | pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| CHST11 | Carbohydrate Sulfotransferase 11 | MMP9 | matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| CHST15 | Carbohydrate Sulfotransferase 15 | MPS VI | Mucopolysaccharidosis VI |

| c-Jun | cellular Jun | OS | Overall Survival |

| COAD | Colon adenocarcinoma | OS* | Osteosarcoma |

| COADREAD | Colon adenocarcinoma/Rectum adenocarcinoma | OV | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma |

| CS | chondroitin sulfate | p38 MAPK | p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| CSE | chondroitin sulfate E | PAAD | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

| DLBC | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma | PCPG | Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid | PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| DS | dermatan sulfate | PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| DSS | Disease-Specific Survival | PI3K/AKT | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| ECM | extracellular matrix | PRAD | Prostate adenocarcinoma |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor | PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor | Rac1 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 |

| EMT | Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition | READ | Rectum adenocarcinoma |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 | SARC | Sarcoma |

| ERT | Enzyme Replacement Therapy | SHP2 | Src Homology 2 Domain-Containing Phosphatase 2 |

| ESCA | Esophageal carcinoma | SKCM | Skin Cutaneous Melanoma |

| FPPP | FFPE Pilot Phase II | Smad3 | Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog 3 |

| GAGs | glycosaminoglycans | Sp1 | Specificity Protein 1 |

| Galectin-3 | Galactoside-Binding Lectin 3 | STAD | Stomach adenocarcinoma |

| GATA-3 | GATA Binding Protein 3 | STES | Stomach and Esophageal carcinoma |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme | TGCT | Testicular Germ Cell Tumors |

| GBMLGG | lower grade glioma and glioblastoma | THCA | Thyroid carcinoma |

| GPNMB | transmembrane glycoprotein NMB; glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein B | THYM | Thymoma |

| H3K27 | Histone H3 Lysine 27 | TME | tumor microenvironment |

| HDAC3 | Histone Deacetylase 3 | UCEC | Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma |

| HNSC | Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma | UCS | Uterine Carcinosarcoma |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal Kinase | UVM | Uveal Melanoma |

| KICH | Kidney Chromophobe | Wnt/β-Catenin | Wingless/Integrated, Beta-Catenin |

| KIPAN | Pan-kidney cohort | Wnt3A | Wingless-Type MMTV Integration Site Family, Member 3A |

| KIRC | Kidney clear cell carcinoma | Wnt9A | Wingless-Type MMTV Integration Site Family, Member 9A |

References

- 1.

Folkman, J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin. Oncol. 2002, 29, 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1053/sonc.2002.37263.

- 2.

Fridman, W.H; Pagès, F; Sautès-Fridman, C; et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3245.

- 3.

Kalluri, R; Fibroblasts in cancer, M; . Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1877.

- 4.

Lu, P; Weaver, V.M; Werb, Z; The extracellular matrix: A dynamic niche in cancer progression. J. Cell. Biol. 2012, 196, 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201102147.

- 5.

Joyce, J.A; Pollard, J.W; Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2618.

- 6.

Hanahan, D; Weinberg, R.A; Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

- 7.

Quail, D.F; Joyce, J.A; Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1423–1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3394.

- 8.

Perera, R.M; Bardeesy, N; Pancreatic Cancer Metabolism: Breaking It Down to Build It Back Up. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1247–1261. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-15-0671.

- 9.

Huang, J; Zhang, L; Wan, D; et al. Extracellular matrix and its therapeutic potential for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00544-0.

- 10.

Karamanos, N.K; Theocharis, A.D; Piperigkou, Z; et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6850–6912. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15776.

- 11.

Hohenester, E; Engel, J; Domain structure and organisation in extracellular matrix proteins. Matrix Biol. 2002, 21, 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00191-3.

- 12.

Rosso, F; Giordano, A; Barbarisi, M; et al. From cell-ECM interactions to tissue engineering. J. Cell. Physiol. 2004, 199, 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.10471.

- 13.

Pomin, V.H; Mulloy, B; Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph11010027.

- 14.

Brown, B; Lindberg, K; Reing, J; et al. The basement membrane component of biologic scaffolds derived from extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12, 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.2006.12.519.

- 15.

Theocharis, A.D; Skandalis, S.S; Gialeli, C; et al. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001.

- 16.

Lawrence, R.E; Zoncu, R; The lysosome as a cellular centre for signalling, metabolism and quality control. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2019, 21, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-018-0244-7.

- 17.

Spill, F; Reynolds, D.S; Kamm, R.D; et al. Impact of the physical microenvironment on tumor progression and metastasis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 40, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.007.

- 18.

Del Prete, A; Schioppa, T; Tiberio, L; et al. Leukocyte trafficking in tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017, 35, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2017.05.004.

- 19.

Fonović, M; Turk, B; Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 2560–2570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.017.

- 20.

Boya, P. Lysosomal function and dysfunction: Mechanism and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 766–774. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2011.4405.

- 21.

Tancini, B; Buratta, S; Delo, F; et al. Lysosomal Exocytosis: The Extracellular Role of an Intracellular Organelle. Membranes 2020, 10, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes10120406.

- 22.

Tobacman, J.K; Bhattacharyya, S; Profound Impact of Decline in N-Acetylgalactosamine-4-Sulfatase (Arylsulfatase B) on Molecular Pathophysiology and Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113146.

- 23.

Modaressi, S; Rupp, K; von Figura, K; et al. Structure of the human arylsulfatase B gene. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler 1993, 374, 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1515/bchm3.1993.374.1-6.327.

- 24.

Litjens, T; Baker, E.G; Beckmann, K.R; et al. Chromosomal localization of ARSB, the gene for human N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulphatase. Hum. Genet. 1989, 82, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00288275.

- 25.

Hanson, S.R; Best, M.D; Wong, C.H; Sulfatases: Structure, mechanism, biological activity, inhibition, and synthetic utility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 5736–5763. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200300632.

- 26.

Prabhu, S.V; Bhattacharyya, S; Guzman-Hartman, G; et al. Extra-lysosomal localization of arylsulfatase B in human colonic epithelium. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011, 59, 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1369/0022155410395511.

- 27.

Brands, M.M; Hoogeveen-Westerveld, M; Kroos, M.A; et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI phenotypes-genotypes and antibody response to galsulfase. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-51.

- 28.

Mathew, J; Jagadeesh, S.M; Bhat, M; et al. Mutations in ARSB in MPS VI patients in India. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2015, 4, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.06.002.

- 29.

Ittiwut, C; Boonbuamas, S; Srichomthong, C; et al. Novel Mutations, Including a Large Deletion in the ARSB Gene, Causing Mucopolysaccharidosis Type VI. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2017, 21, 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/gtmb.2016.0221.

- 30.

Rossi, A; Romano, R; Fecarotta, S; et al. Multi-year enzyme expression in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI after liver-directed gene therapy. Med 2024, 6, 100544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2024.10.021.

- 31.

Malekpour, N; Vakili, R; Hamzehloie, T; Mutational analysis of ARSB gene in mucopolysaccharidosis type VI: Identification of three novel mutations in Iranian patients. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 950–956. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2018.27742.6760.

- 32.

GeneCards. ARSB gene—Arylsulfatase B. GeneCards Human Gene Database 2024. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=ARSB(accessed on 4 June 2025).

- 33.

Tomanin, R; Karageorgos, L; Zanetti, A; et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (MPS VI) and molecular analysis: Review and classification of published variants in the ARSB gene. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1788–1802. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23613.

- 34.

Bhattacharyya, S; Tobacman, J.K; Steroid sulfatase, arylsulfatases A and B, galactose-6-sulfatase, and iduronate sulfatase in mammary cells and effects of sulfated and non-sulfated estrogens on sulfatase activity. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 103, 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.08.002.

- 35.

Bhattacharyya, S; Kotlo, K; Shukla, S; et al. Distinct effects of N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase and galactose-6-sulfatase expression on chondroitin sulfates. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 9523–9530. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M707967200.

- 36.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Terai, K; et al. Decline in arylsulfatase B leads to increased invasiveness of melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 4169–4180. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.13751.

- 37.

Bhattacharyya, S; Insug, O; Tu, J; et al. Exogenous recombinant N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase (Arylsulfatase B., ARSB) inhibits progression of B16F10 cutaneous melanomas and modulates cell signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166913.

- 38.

Ricciardelli, C; Mayne, K; Sykes, P.J; et al. Elevated stromal chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan predicts progression in early-stage prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 1997, 3, 983–992.

- 39.

Feferman, L; Bhattacharyya, S; Deaton, R; et al. Arylsulfatase B (N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase): Potential role as a biomarker in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013, 16, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2013.18.

- 40.

Feferman, L; Deaton, R; Bhattacharyya, S; et al. Arylsulfatase B is reduced in prostate cancer recurrences. Cancer Biomark. 2017, 21, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.3233/cbm-170680.

- 41.

Bhattacharyya, S; Tobacman, J.K; Arylsulfatase B regulates colonic epithelial cell migration by effects on MMP9 expression and RhoA activation. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2009, 26, 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-009-9253-z.

- 42.

Kovacs, Z; Jung, I; Szalman, K; et al. Interaction of arylsulfatases A and B with maspin: A possible explanation for dysregulation of tumor cell metabolism and invasive potential of colorectal cancer. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 3990–4003. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.3990.

- 43.

Wang, W. Functional and Mechanistic Study of Circ RNA ARSB in the Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Thesis, Ph.D; , 2023.

- 44.

Bi, C. The Role of ARSB in Regulating Proliferation, Migration, and Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells through the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Thesis, Master’s; , 2023.

- 45.

Gasa, S; Makita, A; Kameya, T; et al. Elevated activities and properties of arylsulfatases A and B and B-variant in human lung tumors. Cancer Res. 1980, 40, 3804–3809.

- 46.

Gasa, S; Makita, A; Phosphorylation on protein and carbohydrate moieties of a lysosomal arylsulfatase B variant in human lung cancer transplanted into athymic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 5034–5039.

- 47.

Figlioli, G; Köhler, A; Chen, B; et al. Novel genome-wide association study-based candidate loci for differentiated thyroid cancer risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2084–E2092. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1734.

- 48.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Han, X; et al. Decline in arylsulfatase B expression increases EGFR expression by inhibiting the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 and activating JNK in prostate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 11076–11087. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA117.001244.

- 49.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Arylsulfatase B regulates versican expression by galectin-3 and AP-1 mediated transcriptional effects. Oncogene 2014, 33, 5467–5476. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.483.

- 50.

Ricciardelli, C; Mayne, K; Sykes, P.J; et al. Elevated levels of versican but not decorin predict disease progression in early-stage prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4, 963–971.

- 51.

Ricciardelli, C; Sakko, A.J; Ween, M.P; et al. The biological role and regulation of versican levels in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-009-9182-y.

- 52.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Chondroitin sulfatases differentially regulate Wnt signaling in prostate stem cells through effects on SHP2, phospho-ERK1/2, and Dickkopf Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor (DKK3). Oncotarget 2017, 8, 100242–100260. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22152.

- 53.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Han, X; et al. Increased CHST15 follows decline in arylsulfatase B (ARSB) and disinhibition of non-canonical WNT signaling: Potential impact on epithelial and mesenchymal identity. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 2327–2344. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.27634.

- 54.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Inhibition of Phosphatase Activity Follows Decline in Sulfatase Activity and Leads to Transcriptional Effects through Sustained Phosphorylation of Transcription Factor MITF. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153463.

- 55.

Bhattacharyya, S; O-Sullivan, I; Tobacman, J.K; N-Acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase (Arylsulfatase B) Regulates PD-L1 Expression in Melanoma by an HDAC3-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115851.

- 56.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Regulation of chondroitin-4-sulfotransferase (CHST11) expression by opposing effects of arylsulfatase B on BMP4 and Wnt9A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1849, 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.12.009.

- 57.

Kovacs, Z; Banias, L; Osvath, E; et al. Synergistic Impact of ARSB, TP53, and Maspin Gene Expressions on Survival Outcomes in Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Clinicopathological Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5721.

- 58.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Restriction of Aerobic Metabolism by Acquired or Innate Arylsulfatase B Deficiency: A New Approach to the Warburg Effect. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32885. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32885.

- 59.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Dihydrotestosterone inhibits arylsulfatase B and Dickkopf Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor (DKK)-3 leading to enhanced Wnt signaling in prostate epithelium in response to stromal Wnt3A. Prostate 2019, 79, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.23776.

- 60.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Tobacman, J.K; Increased expression of colonic Wnt9through SpA1-mediated transcriptional effects involving arylsulfatase B, chondroitin 4-sulfate, and galectin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17564–17575. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.561589.

- 61.

Tobacman, J.K; Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Abstract 4699: Decline in Arylsulfatase B (ARSB) increases PD-L1 expression in melanoma, hepatic, prostate, and mononuclear cells. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 4699. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.Am2020-4699.

- 62.

Bhattacharyya, S; Feferman, L; Sharma, G; et al. Increased GPNMB, phospho-ERK1/2, and MMP-9 in cystic fibrosis in association with reduced arylsulfatase B. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 124, 168–175.

- 63.

Arabi, F; Mansouri, V; Ahmadbeigi, N; Gene therapy clinical trials, where do we go? An overview. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113324.

- 64.

Amer, M.H. Gene therapy for cancer: Present status and future perspective. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2014, 2, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-8426-2-27.

- 65.

Au, J.L; Jang, S.H; Wientjes, M.G; Clinical aspects of drug delivery to tumors. J. Control. Release 2002, 78, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00488-6.

- 66.

Kraehenbuehl, L; Weng, C.H; Eghbali, S; et al. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00552-7.

- 67.

Tang, J; Yu, J.X; Hubbard-Lucey, V.M; et al. Trial watch: The clinical trial landscape for PD1/PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 854–855. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.210.

- 68.

Baumeister, S.H; Freeman, G.J; Dranoff, G; et al. Coinhibitory Pathways in Immunotherapy for Cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 34, 539–573. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112049.

- 69.

Shah, R; Singh, J; Singh, D; et al. Sulfatase inhibitors for recidivist breast cancer treatment: A chemical review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 114, 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.02.054.

- 70.

Zu, H; Gao, D; Non-viral Vectors in Gene Therapy: Recent Development, Challenges, and Prospects. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 78. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-021-00608-7.

- 71.

Valkenburg, K.C; de Groot, A.E; Pienta, K.J; Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-018-0007-1.

- 72.

Wan, P.K; Ryan, A.J; Seymour, L.W; Beyond cancer cells: Targeting the tumor microenvironment with gene therapy and armed oncolytic virus. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1668–1682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.015.

- 73.

Kovacs, Z; Jung, I; Gurzu, S; Arylsulfatases A and B: From normal tissues to malignant tumors. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2019.152516.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.