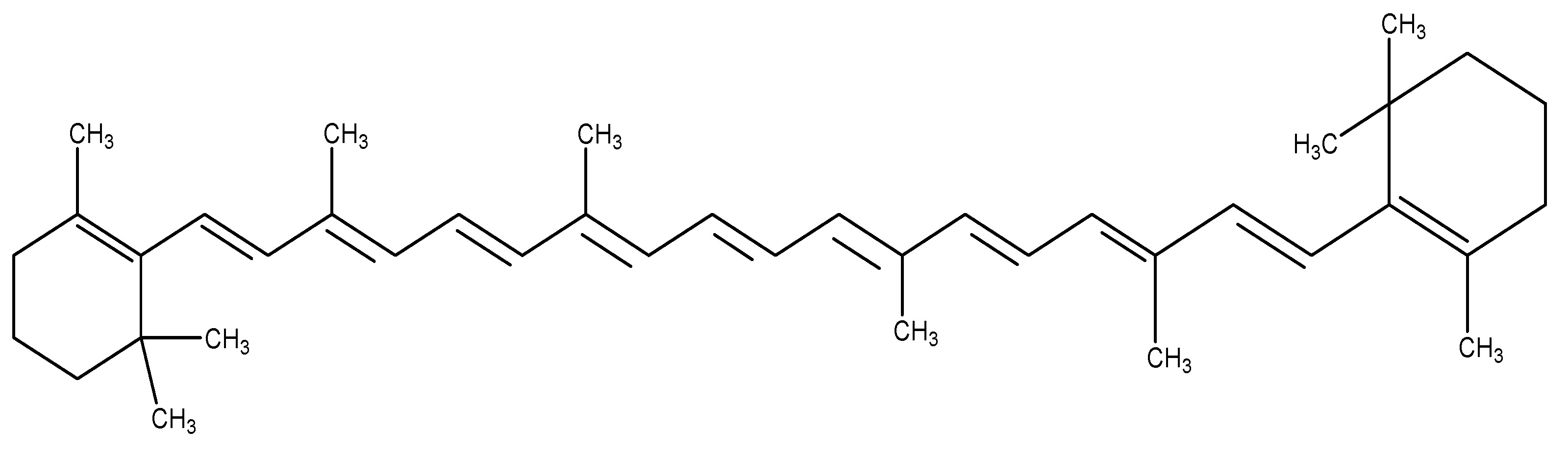

The rising global prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and obesity has intensified the search for novel therapeutic agents, with Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) emerging as a key regulator of glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion. While synthetic GLP-1 receptor agonists (RAs) like semaglutide and tirzepatide dominate clinical use, plant-derived GLP-1 modulators present a promising alternative due to their natural origin, diverse mechanisms, and potential for reduced side effects. This review systematically evaluates 34 medicinal plants—including Agave tequilana (fructans), Berberis vulgaris (berberine), Momordica charantia (bitter melon), and Panax ginseng (ginsenosides)—that exhibit GLP-1 agonist activity through pathways such as DPP-4 inhibition, bitter taste receptor activation, and SCFA-mediated GLP-1 secretion. Comparative analysis reveals that while synthetic agonists offer superior HbA1c reduction (1–2%) and weight loss (5–22.5%), natural compounds provide multimodal benefits, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and beta-cell protective effects. However, clinical evidence remains limited, with most studies confined to preclinical models. Future research should prioritize human trials, bioavailability optimization, and synergistic formulations to harness the full therapeutic potential of plant-derived GLP-1 agonists in metabolic disorders.

- Open Access

- Review

Natural Products Targeting GLP-1: Insights into Herbal Therapy for Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Function

- Akshita Vyas,

- Shraddha Mahajan,

- Sumeet Dwivedi,

- Sweta S. Koka *,

- Gajanan N. Darwhekar

Author Information

Received: 11 Jun 2025 | Revised: 29 Jul 2025 | Accepted: 31 Jul 2025 | Published: 27 Jan 2026

Abstract

Keywords

GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) | type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) | natural products | therapeutic agents | incretin | gut hormone | insulin secretion

1. Introduction

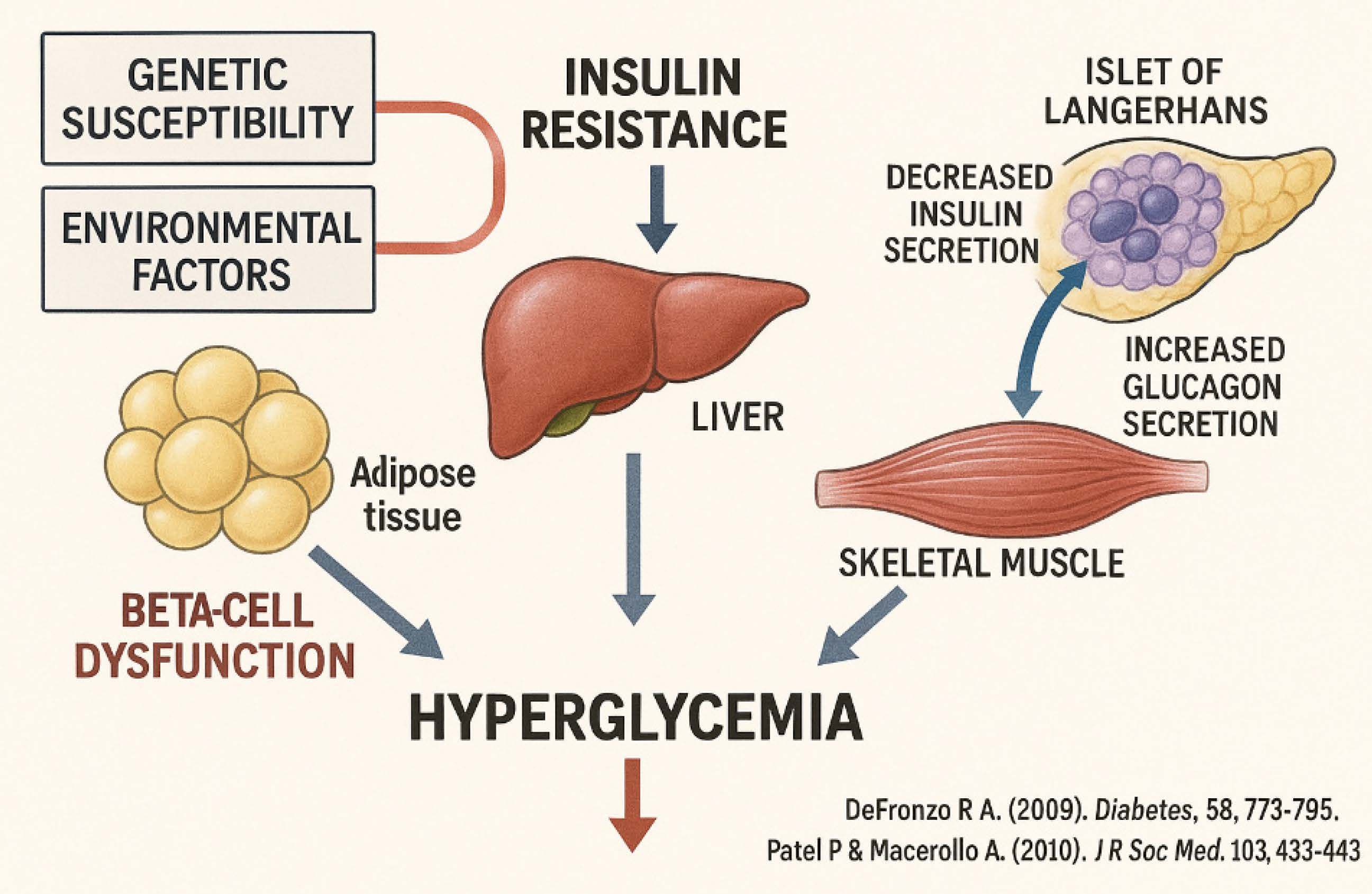

Diabetes mellitus continues to pose a global health concern, impacting around 537 million adults in 2021, with forecasts increasing to 783 million by 2045 [1]. Recent developments in diabetes management have emphasized precision medicine, AI-driven glucose monitoring, and innovative medications. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems, such the Dexcom G7 and Abbott Freestyle Libre 3, now provide real-time, non-invasive glucose tracking with enhanced precision [2]. Furthermore, closed-loop insulin administration devices (artificial pancreas) have shown a 27% decrease in hypoglycemia in individuals with type 1 diabetes [3]. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, has demonstrated a greater reduction in HbA1c (up to 2.4%) than conventional GLP-1 agonists [4]. Advancements in stem cell therapy, namely pancreatic islet transplantation, have been noted, with recent trials demonstrating insulin independence in 60% of recipients after five years. These advances highlight a transition towards individualized, technology-enhanced diabetes management, ensuring better results for patients globally [5]. As shown in Figure 1.

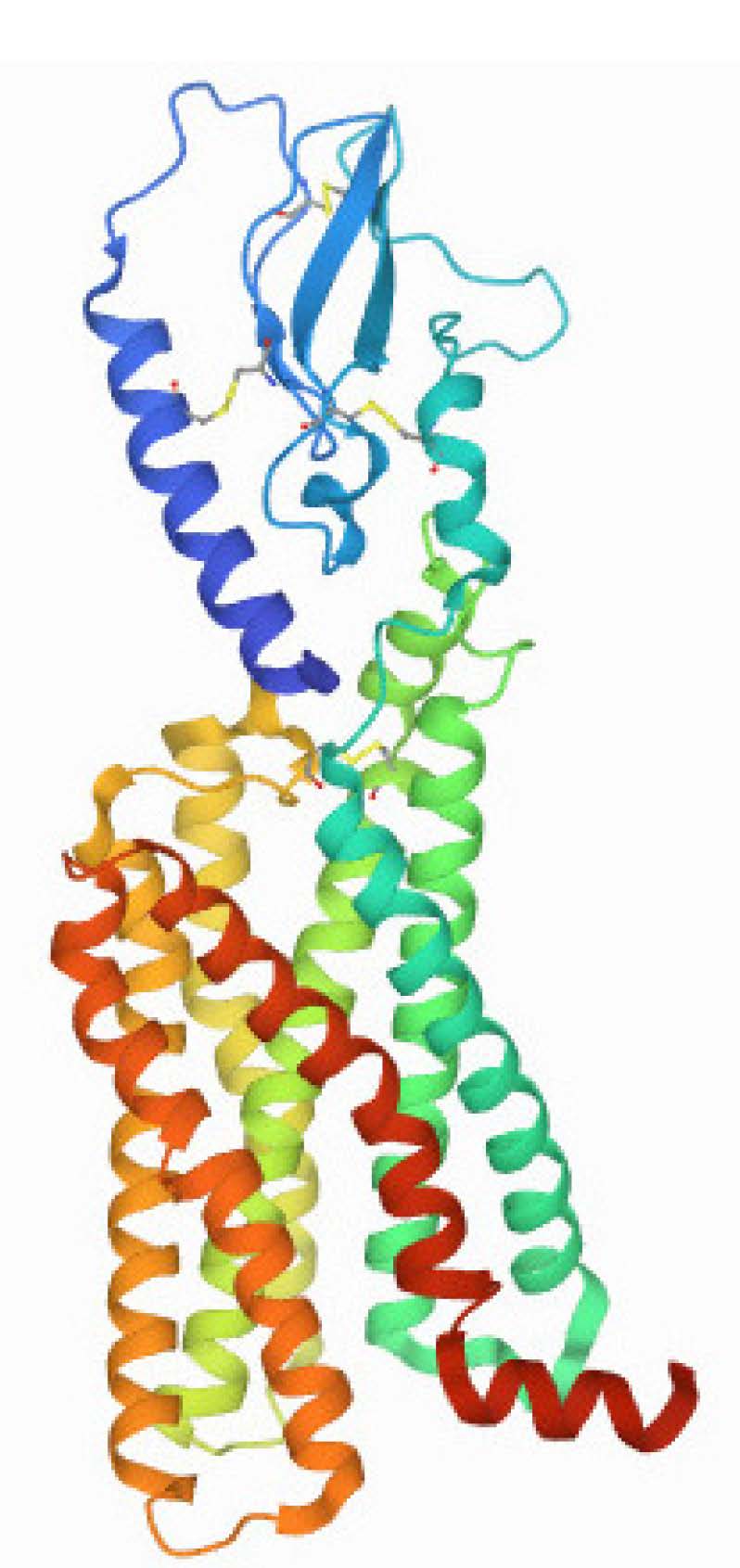

Historically, natural products have demonstrated considerable potential as a source of drug discovery with the help of their chemical structure and recent endeavors on this field have focused on investigating the GLP-1 activating capabilities of various products which are naturally sourced from traditionally employed medicinal flora or nutritional origins. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) controls insulin release from the pancreas, which in turn controls glucose homeostasis. GLP-1 agonists are useful drugs for the treatment of diabetes. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is a member of the class B family of peptide hormone G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). A significant N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) is the defining structural and functional feature of these receptors. The ECD is a universally defined structure featuring trilayer α-β-βα folds, supported by three conserved pairs of cysteine disulfide linkages. The identified compounds are mostly are selective GLP-1 modulators; In contrast to completely synthesized agonists, these natural GLP-1 modulators show distinct receptor binding mechanisms. Consequently, an effort has been made to review various plant-derived products possessing GLP-1 activating properties, specifically those acting as agonists on the GLP-1 receptor, which demonstrate interactions with both the catalytic site and the secondary binding site present in the GLP-1 receptor [8].

2. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1

A hyperglycaemic factor was discovered in the pancreatic islets within two years of the identification of insulin in 1921. Designated ‘GLUCAGON’, it is a single-chain polypeptide consisting of 29 amino acids, secreted by alpha cells of the islets of Langerhans and produced commercially by recombinant DNA technology [9]. As shown in Figure 2.

The endogenous incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) plays a prominent role in maintaining glucose homeostasis. GLP-1 is a 30-amino acid peptide secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake, released from pro-glucagon by the action of pro-hormone convertase, which processes preproglucagon, the precursor of several glucagon-related peptides. It appears in two variants, GLP-1 (7-36)-NH2 and GLP-1 (7-37). There is baseline secretion of GLP-1 even during fasting (5–10 pm), but postprandially induced production increases with meal size (10–30 pm). Postprandial secretion occurs in two phases; the primary phase begins within minutes and lasts for up to 60 min, after by a secondary phase that continues for up to 120 min after the meal [10].

The pancreas, brain, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract are among the organs that contain GLP-1. A recent study revealed that it is primarily expressed in pancreatic beta cells and seldom in alpha cells. Consuming carbohydrates, proteins, and fats causes the release of GLP-1 into the bloodstream; however, the exact mechanism of action for glucose is still being elucidated. DPP-4 degrades GLP-1, leading to the formation of biologically inactive metabolites [10].

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist:

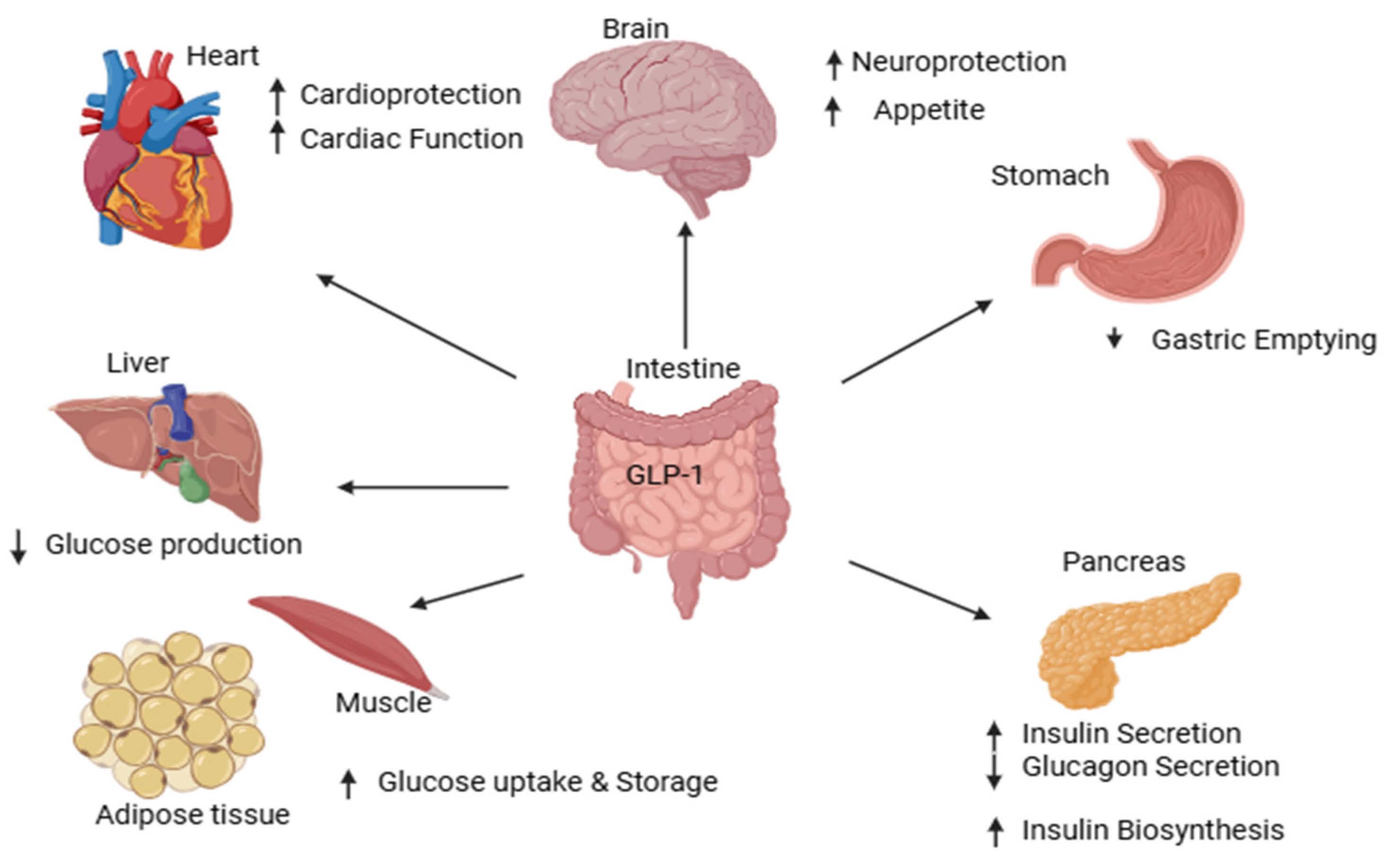

The gastrointestinal tract releases GLP-1, a major incretin, in response to glucose consumption. It delays stomach emptying, inhibits appetite by activating specific GLP-1 receptors, increases insulin production from pancreatic beta cells, and lowers glucagon secretion from alpha cells. GLP-1 usually only increases insulin production when blood glucose levels are high [11].

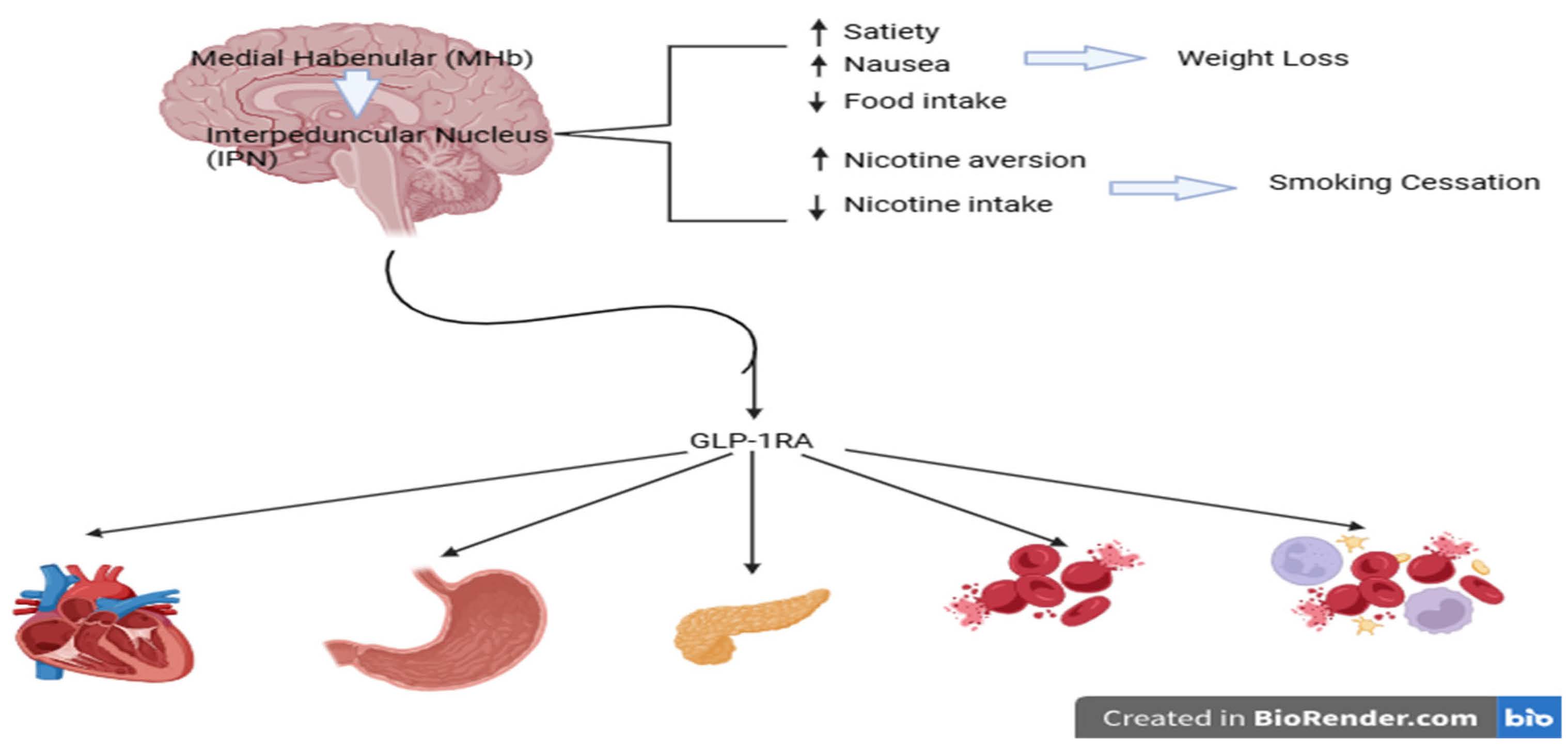

Recent studies shows that GLP-1 receptor agonists are effective adjuncts to metformin for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially for patients aiming to prevent weight gain or hyperglycemia. They are optimal for their insulinotropic effect exclusively when glucose levels are elevated, thereby providing the capacity to decrease plasma glucose while mitigating the risk of hypoglycemia. Additionally, this agonist inhibits glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, slows gastric emptying, and exerts effects by acting on the central nervous system [12]. As shown in Figure 3.

There are primarily two types of GLP-1 agonists, which are as follows:

(1) Short-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist: This class of agonists is identified by brief spikes in plasma drug concentrations following each injection, followed by sporadic intervals of very zero concentrations. The temporal action profile thus alternates between “resting” periods (during which GLP-1 receptors are not activated) and intervals (lasting several hours) during which patients are exposed to effective circulating drug concentrations.

(2) Long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist: This class of receptor agonists is characterized by consistently high drug concentrations that fall within a range that allows for substantial GLP-1 receptor stimulation with negligible inter-injection variations. This definition takes pharmacokinetics into account in addition to injection frequency [13].

3. Mechanism of Action of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist

This receptor agonist’s action relates to normal glucose tolerance; in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, the incretin effect is responsible for less than 20% of the insulin response to an oral glucose load, whereas it accounts for roughly two-thirds of the response. As a result, postprandial hyperglycemia may arise from a compromised incretin response, which may be particularly important during the postprandial period [14]. As shown in Figure 4.

Natural GLP-1 receptor agonist:

The kingdom of plants has great promise for the development of novel medications to treat a range of conditions, including diabetes mellitus. The literature study demonstrates the utilization of botanical and plant-derived treatments for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The following are natural GLP-1 receptor agonists utilized for type 2 diabetes mellitus:

(1) Agave

Biological name—Agave tequilana Gto.

Synonyms—Agave tequilana, Tequila agave and Agave angustifolia.

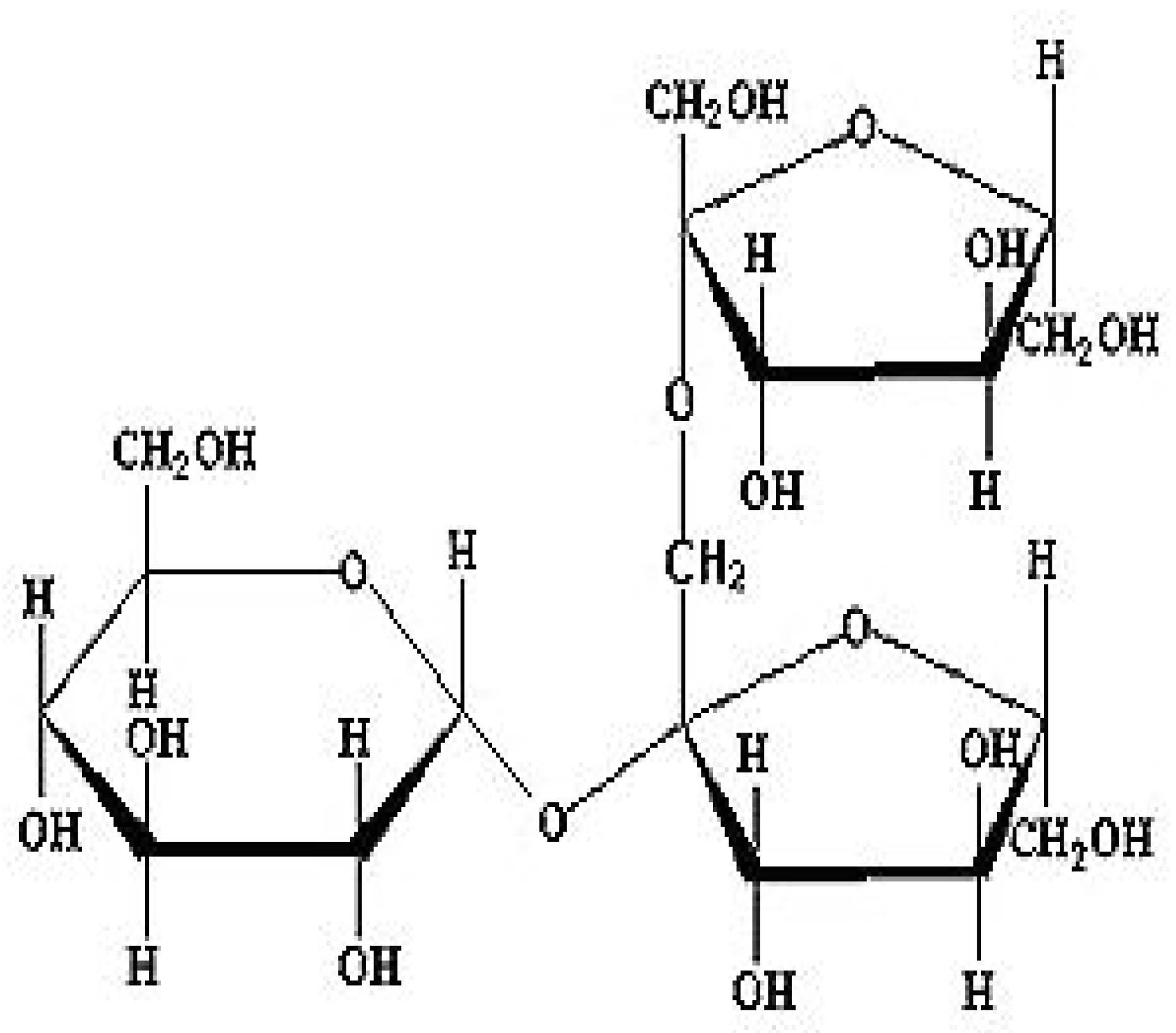

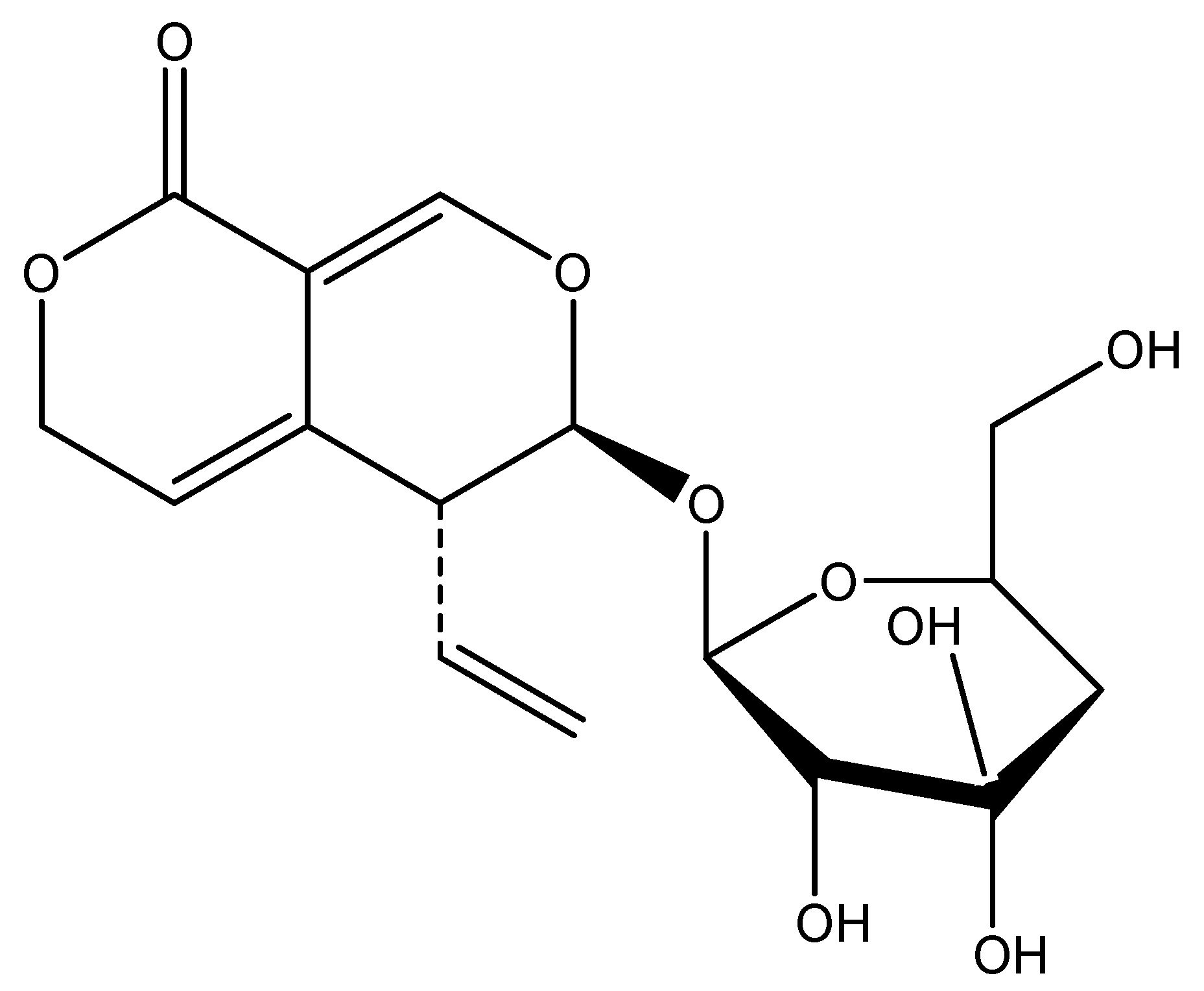

Agave is a remarkable commercial commodity in Jalisco, Mexico, as it known as the primary ingredient for tequila. This family, Agavaceae, is mostly obtained from dietary fiber, carbohydrates, proteins and fats. Fructans present in agave is stimulated GLP-1 production and increased the levels of its precursors. Fructan is a primary phytochemical in Agave plant. Recent results indicate that fructans derived from chicory roots influence appetite and metabolism of glucose while boosting GLP-1 synthesis in the colon. The roots are utilized for the induction of GLP-1, with agave fructan as the primary phytochemical. The data from recent research indicates that supplementation with 10% fructans in male C57BL/6J mice demonstrates action [15]. As shown in Scheme 1.

(2) Berberis

Scientific name—Berberis vulgaris.

Synonyms—Berberis acida and European barberry.

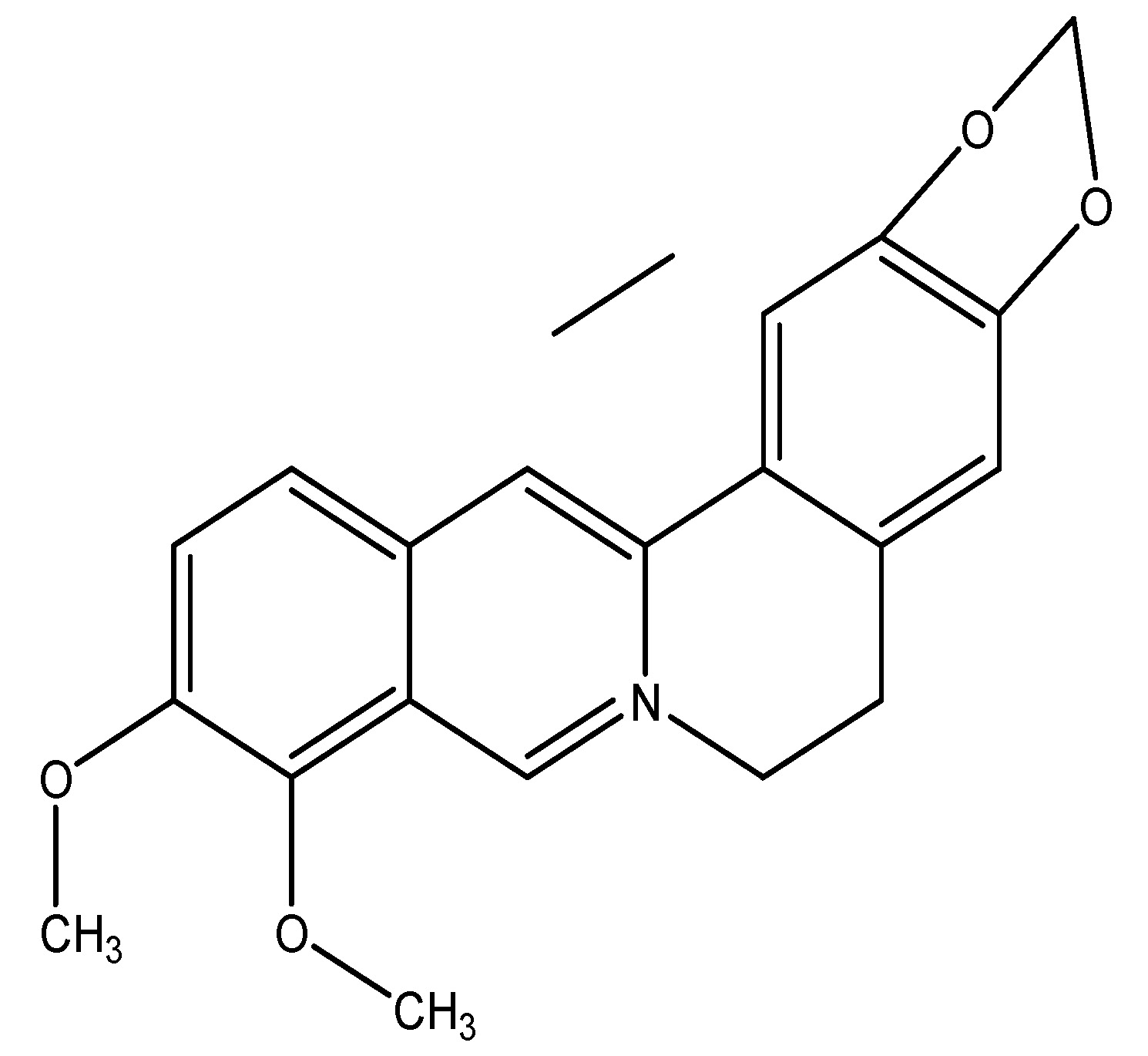

Barberry is a fruit and its plant is a shrub belonging to the Berberidaceae family, producing edible yet strongly acidic berries that are used as a tart and refreshing fruit in several nations. The primary phytochemical is berberine. According to the data administering 500 mg/kg of this substance in rats has shown an antidiabetic effect, attributable to berberine, which enhances insulin production and stimulates glycolysis. Berberine enhances the levels of glucose transporter-4 (GLUT-4) and GLP-1. The primary components utilized are roots and rhizomes [16]. As shown in Scheme 2

(3) Bitter Hop

Scientific name—Humulus lupulus.

Synonyms—Hope, Lupulus amarus and Humulus vulgaris Gilib.

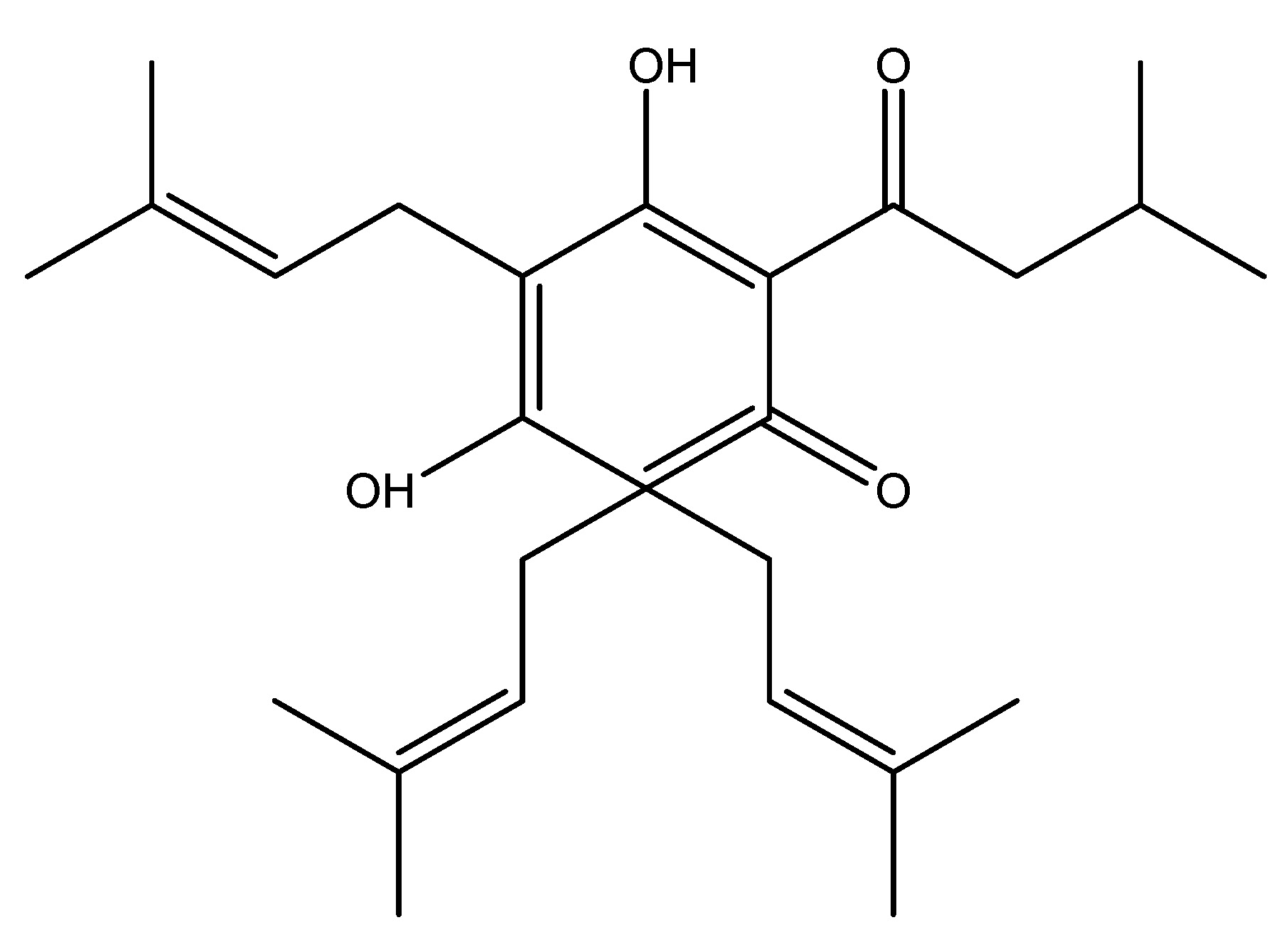

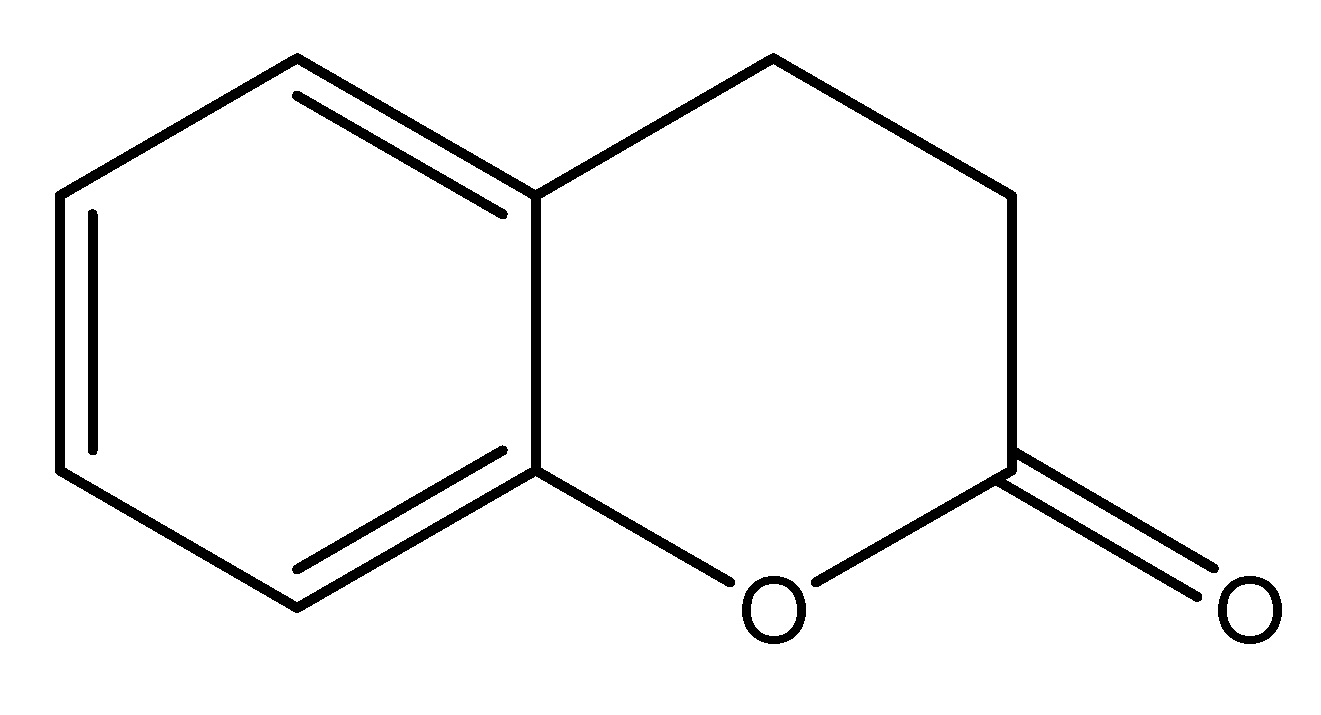

The Bitter hop is a flowering plant species belonging to the Cannabaceae family. It is mainly found in indigenous to Europe, western Asia, and North America. It is a perennial herbaceous vine that produces new shoots in the plants in early spring and reverts to a cold-hardy rhizome in autumn. This significantly contributes to the astringent quality of beer. The bitter taste receptor has been demonstrated to affect the release of many gut hormones, primarily glucagon-like peptide, which is implicated in the process of regulation of glucose homeostasis. The chemical constituents found in bitter hop include humulone, lupulone, xanthohumol and adlupulone. It is involving the endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract and their action as a possible therapeutic target for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus due to their activation of GLP-1, which results in a hypoglycemic impact [17]. As shown in Scheme 3.

(4) Bitter Melon (Karela)

Scientific name—Momordica charantia.

Synonyms—Balsam apple, Balsam pear, Bitter gourd, and Karela (India).

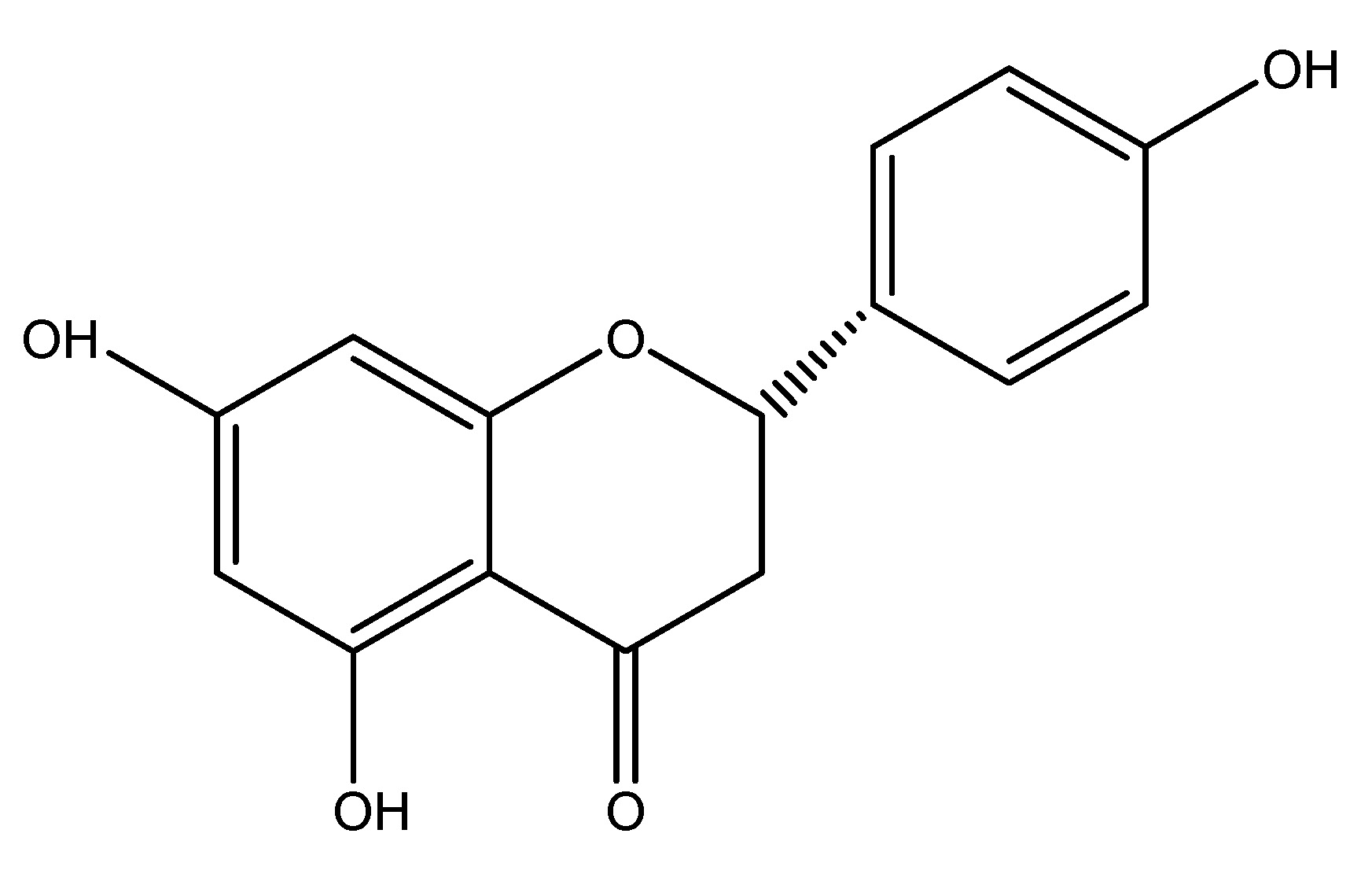

Bitter melon also known as karela is a tropical and subtropical vine belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family, extensively cultivated in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. Also, it is known as edible fruit which exhibits significant variation in shape and bitterness throughout its numerous variations. The plant derives its name from its increasingly bitter taste as it ripens, which is associated with reduced blood sugar levels. Some research indicate that this may aid in diabetes treatment, mostly with its fruit. The primary phytochemical is Karavilagenine E. In the study, the administration of 5000 mg/kg of bitter melon orally and in conjunction with a single dosage of WES for 30 min in mice resulted in elevated serum levels of GLP-1 and insulin and reduced glucose levels; also, WES was found to increase GLP-1 secretion in vivo [18]. As shown in Scheme 4.

(5) Black Chokeberry

Scientific name—Aronia melanocarpa.

Synonyms—Aronia nigra and Photinia melanocarpa.

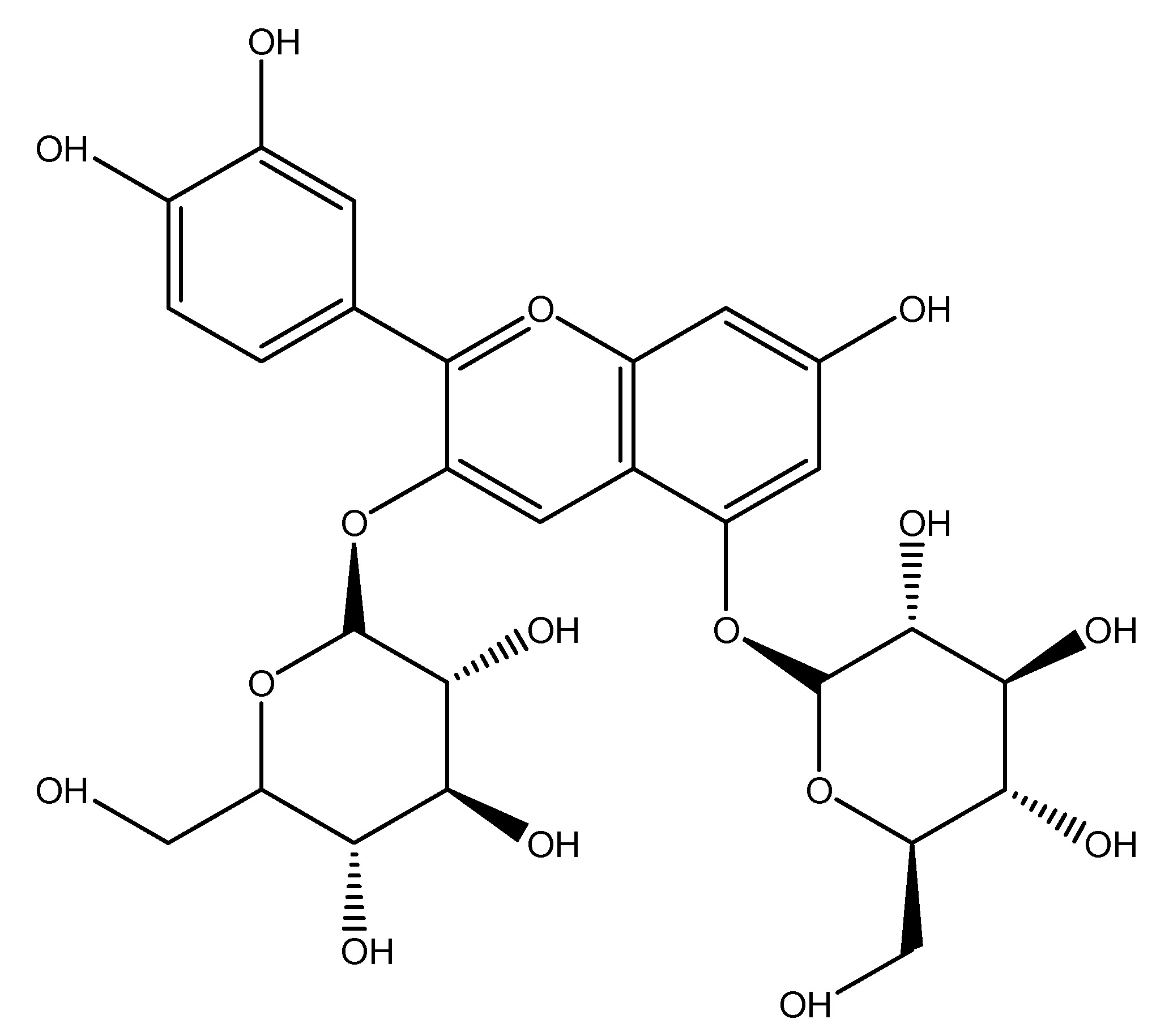

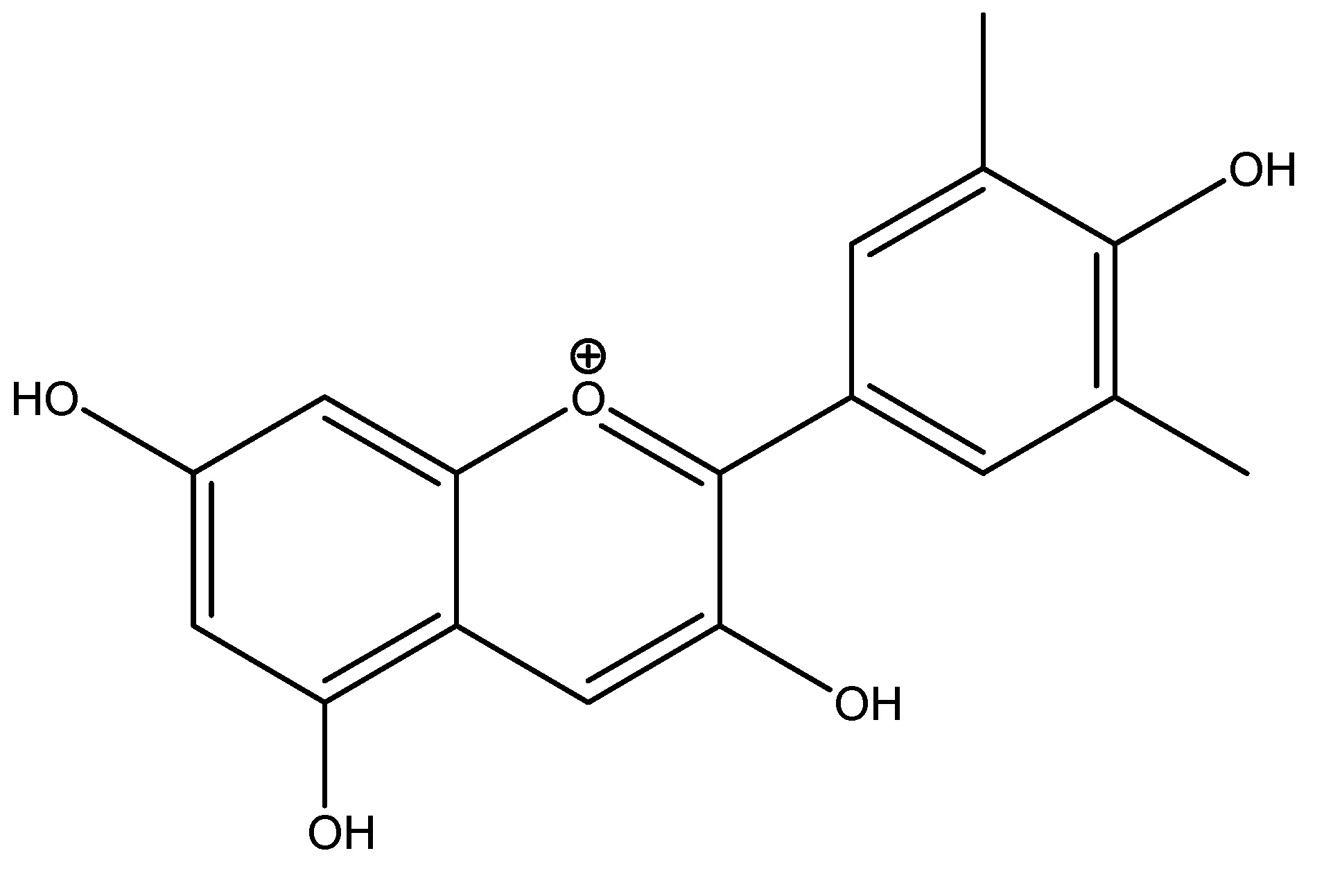

Black chokeberry is a Fruit species and its plant is shrub in the rose family native to eastern North America to extending from Canada to the central United States. This plant is belonging to the family Rosaceae and it is characterized by its glossy dark green leaves. Black chokeberry fruits are the richest sources of polyphenols and anthocyanins with chemical elements including malic acid, quinic acid, and ascorbic acid. The active molecule utilized in research studies is cyanidin 3,5-diglucoside and also juice of Black chokeberry is employed in studies. The application of an IC50 of 5.5 µM in vitro results in DPP-4 inhibition and elevates GLP-1 levels by interacting with these receptors [19]. As shown in Scheme 5.

(6) Black Currant

Scientific Name—Ribes nigrum.

Synonyms—Cassis, Ribes nigrum, Passiflora edulis, and Rubus idaeus.

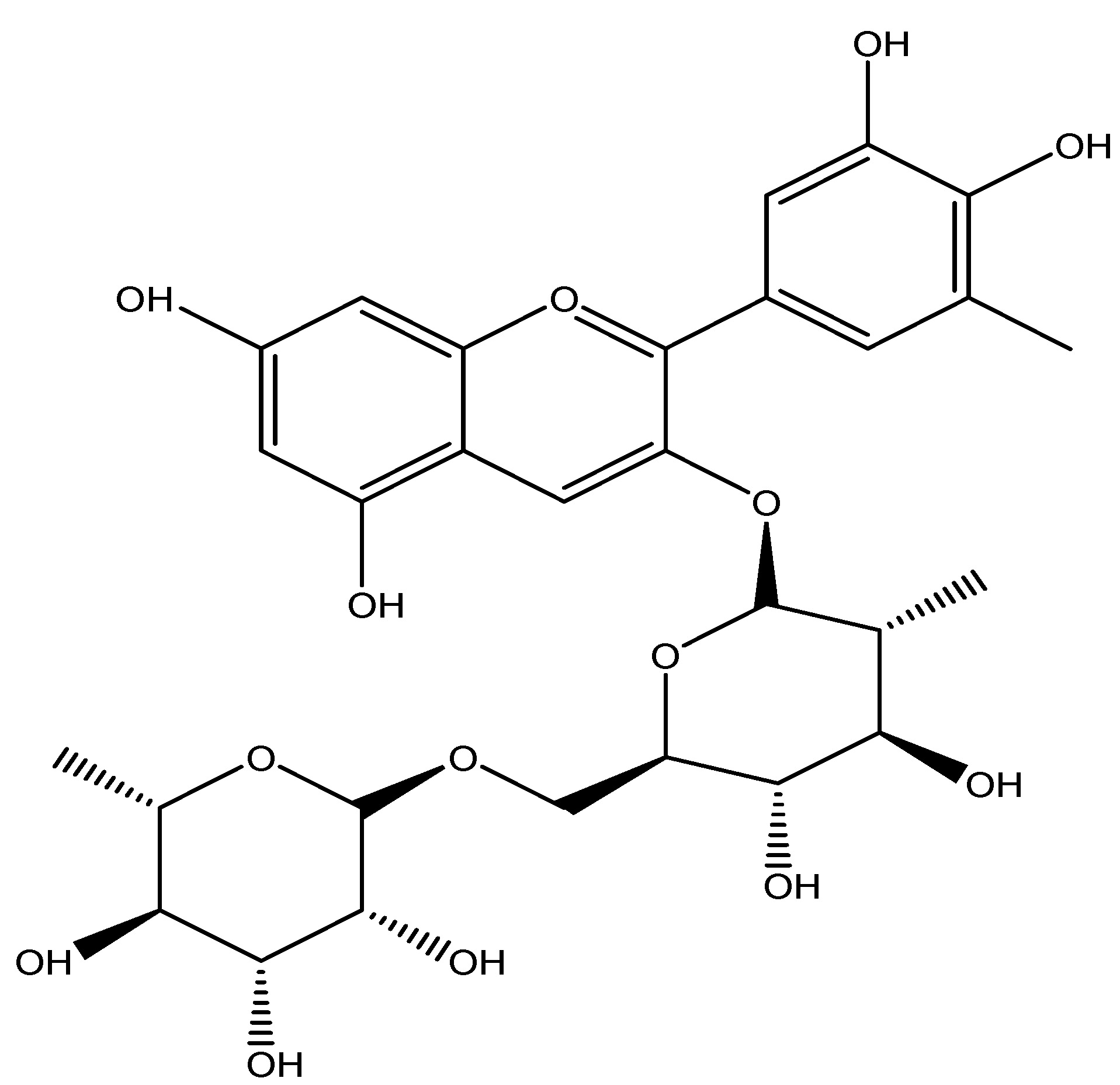

The black currant is an also berry or a fruit which is deciduous shrub plant. It is belonging to the Grossulariaceae family and cultivated for its tasty berries. It is found in indigenous to temperate regions of central and northern Europe and northern Asia thriving in fertile soils. This plant is winter hardy with its fruit that exhibits enhanced disease resistance and fruits are rich in vitamin C and polyphenols. The chemical constituents of Ribes nigrum include glucose, fructose, malic acid and citric acid. The primary active component of black current is Delphinidin 3-rutinoside. The Administration of 5 mg/kg of Ribus nigrum fruit alongside 1 mg/kg of delphinidin 3-rutinoside in GLUT ag cells enhances the GLP-1 and insulin production [20]. As shown in Scheme 6.

(7) China Mongolia

Scientific name—Anemarrhena asphodeloides.

Synonyms—Terauchia anemarrhenifolia Nakai and Zhi mu.

Anemarrhena asphodeloids qualifies as a bitter-tasting medicinal plant and its common name is China Mongolia. It has been documented to enhance GLP-1 secretion, primarily aiding in the maintenance of healthy blood glucose levels. Anemarrhena is a genus of the Asparagaceae family which is commonly known as China magnolia because it is mostly found in China. The plant known as Zhi mu in China has its rhizome utilized in traditional Chinese medicine and exhibits properties such as diuretic and laxative effects among others. Anemarrhena comprises steroidal saponins, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, benzophenones, and alkaloids which are its main phytochemical constituents. The model for investigation of China Mongolia is the Human L cell line [21]. As shown in Scheme 7.

(8) Chinese Throughawax

Scientific Name—Bupleurum falcatum.

Synonyms—Bupleurum alpinum Nyman and Bupleurum diversifolium Rochel.

Bupleurum falcatum has been traditionally utilized as a medicinal herb in Korean medicine belonging to the Apiaceae family. Bupleurum falcatum has been utilized in Chinese medicine form more than 2000 years as a “liver tonic”. It enhances GLP-1 production and researchers suggests that the medicinal herb may serve as a therapeutic agent for diabetic mellitus. This flowering plant, sometimes referred to as sickle-leaved or hare’s-ear Chinese through wax, contains dietary polyphenols found in green tea. It reduces blood glucose levels and stimulates GLP-1 secretion via a G-protein mediated pathway, while also enhancing the insulin secretion through the modulation of ATP-dependent potassium channel thereby increasing calcium influx from intracellular reserves. Bupleurum comprises saponins, flavonoids, monoterpene glycosides, as well as coumarins and lignins as its chemical constituents. According to research data NCI-H716 cells were treated with three dosages: 100, 200, and 500 µg/mL in db/db mice, resulting in a dose-dependent increase in GLP-1 secretion, with all concentrations significantly enhancing GLP-1 secretion in the human L cell line [22]. As shown in Scheme 8.

(9) Chinese Yam

Scientific name—Dioscorea polystachya.

Synonyms—Korean yam, Cinnamon vine, Dioscorea batatas.

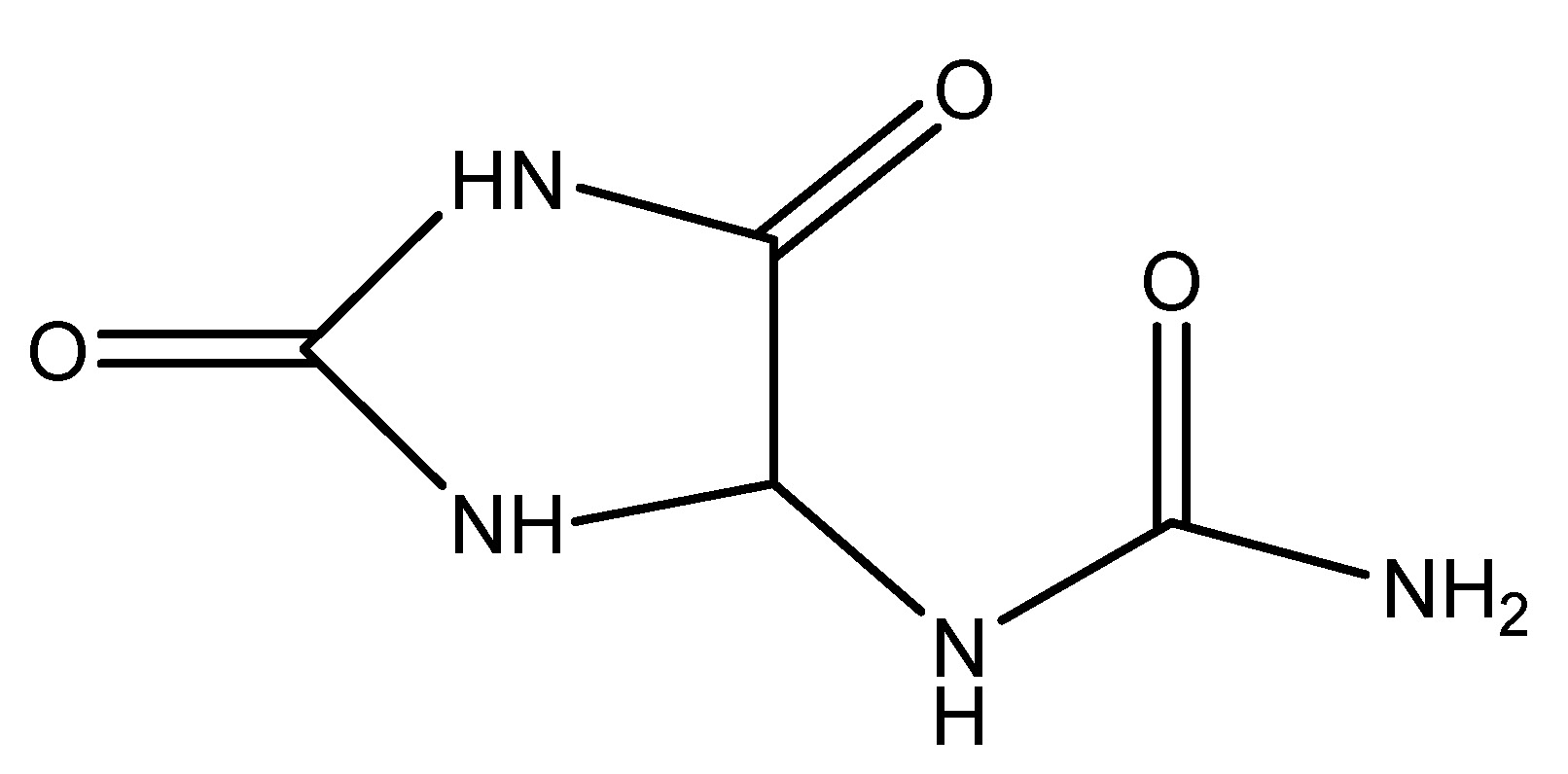

Chinese yam is a species of flowering plant in family, this is occasionally referred as Chinese potato or by its Korean name. This species belongs to the Dioscoreaceae family and is a perennial climbing vine indigenous to China and East Asia, utilized in traditional medicine. The yam is distinctive because its tubers are consumable in their uncooked state. The primary active ingredient of Chinese yam is Allantoin, which is delivered intravenously at a dose of 2 mg/kg in STZ-treated Sprague-Dawley rats, resulting in an increased release of GLP-1 [23]. As shown in Scheme 9.

(10) Cinnamon Tree

Scientific name—Cinnamomum zeylanicum.

Synonyms—Cinnamomum verum, Cinnamon, Ceylon cinnamon.

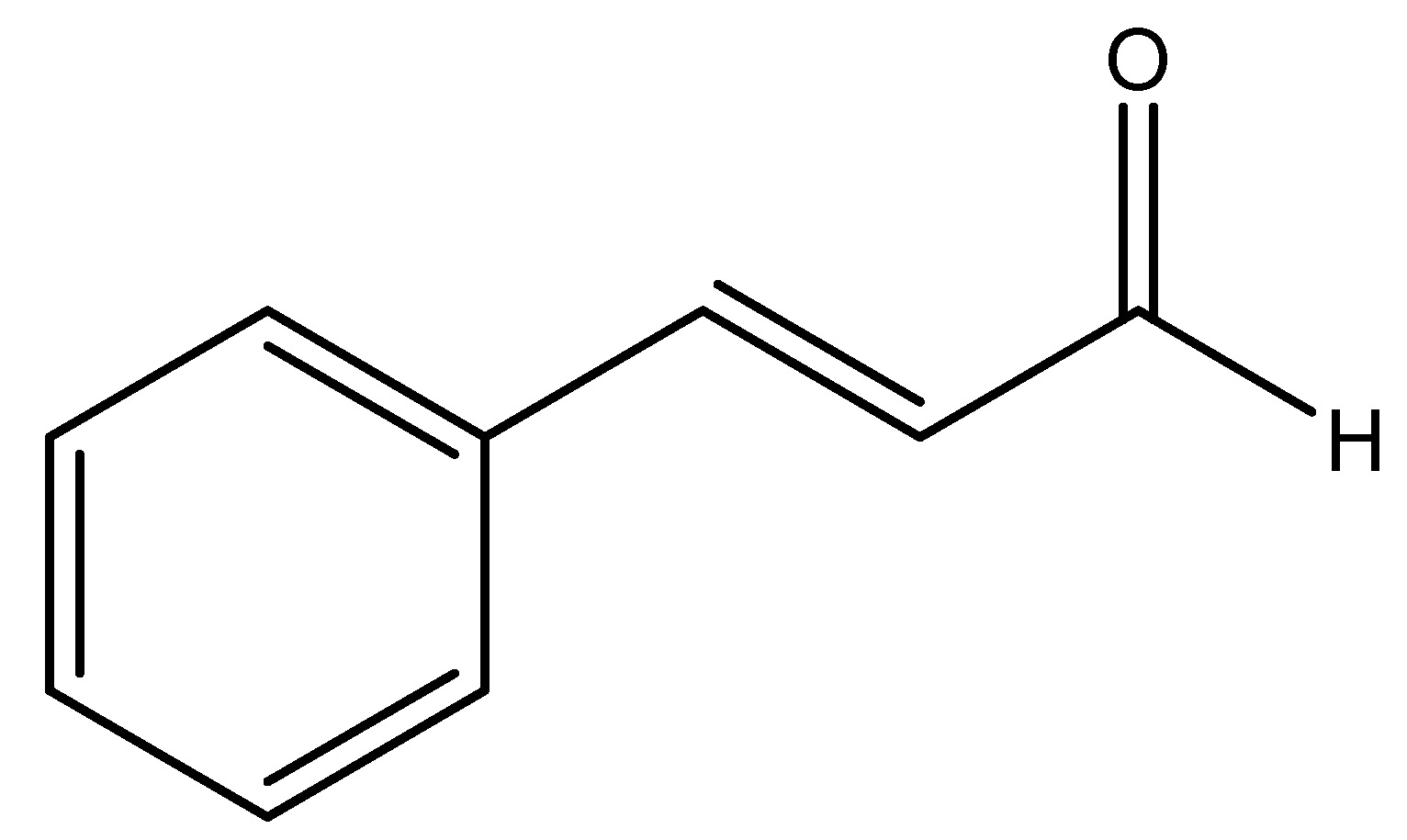

Cinnamon is a little evergreen tree belongs to the Lauraceae family, indigenous to Sri Lanka, characterized by a more nuanced flavor that renders it preferable for specific culinary applications. The bark of this tree is utilized and is presently promoted as a treatment for glucose intolerance, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. Integrative medicine which is a novel idea that amalgamates conventional treatment with evidence-based remedies. Cinnamaldehyde, cinnamate and cinnamic acid are the chemical constituents of cinnamon plants. Plexopathy exhibited a dose-dependent which is decrease in serum insulin levels and an elevation in glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) following cinnamon treatment. Similarly, in studies reported that the incorporation of 3 g of cinnamon into a rice meal in humans resulted in a significant increase in GLP-1 levels alongside a reduction in serum insulin. Enhanced glucose transfer across the cell membrane diminishes insulin resistance, perhaps explaining the decreased insulin levels [24]. As shown in Scheme 10.

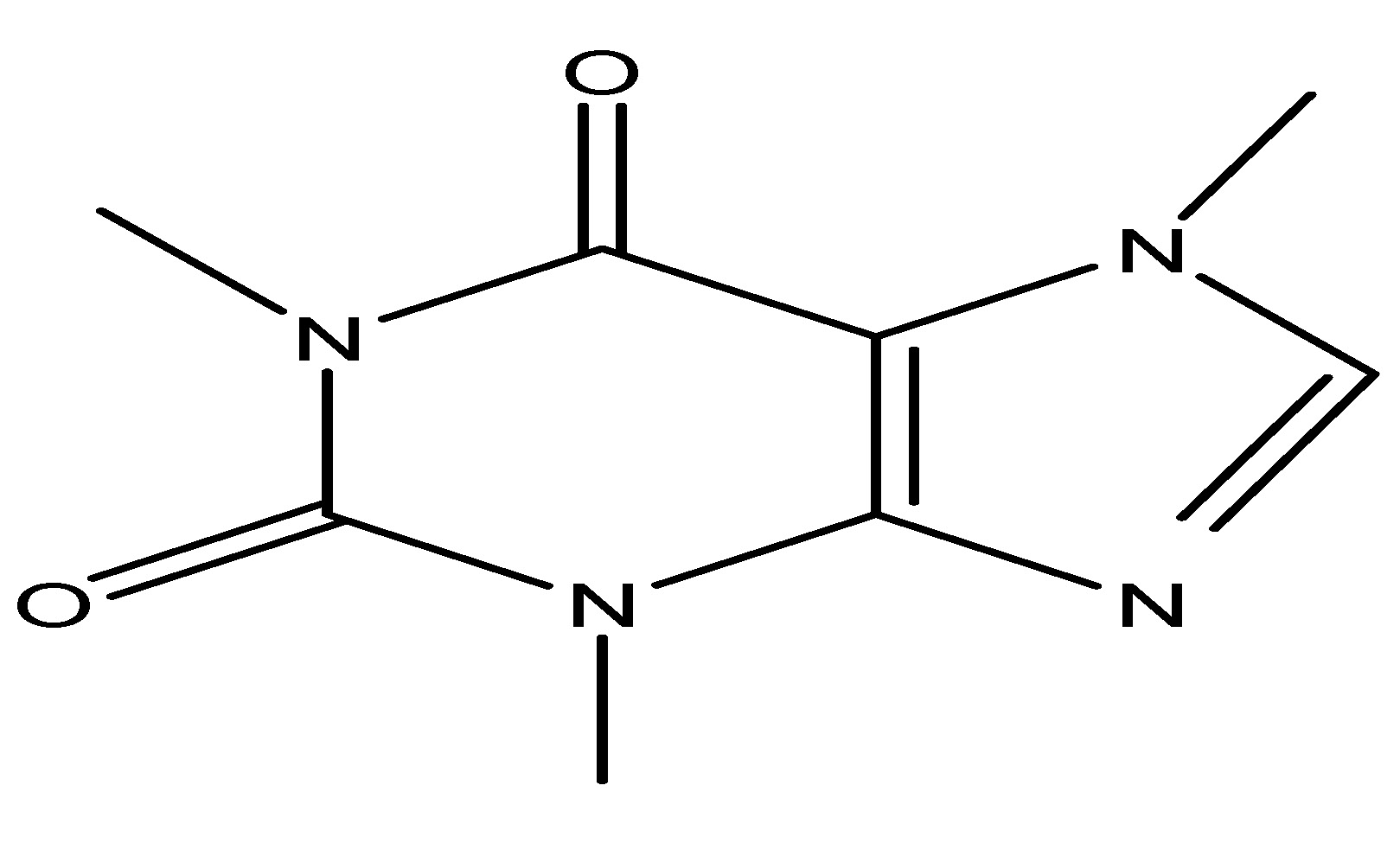

(11) Coffee

Scientific name—Coffea arabica.

Synonyms—Theobroma pentagonum, Theobroma sativum, and cocoa.

The cacao tree is a little evergreen species belonging to the Malvaceae family. The beans are utilized for coffee, making it one of the most widely used beverages globally. These beans are mostly derived from the cocoa plant and obroma cacao. The active phytochemical constituent present in this plant is caffeine, which is effective in glycemic control and it is shown that it reducd lower blood glucose levels in animal studies. Coffee drinking may also influence levels of GLP-1. In healthy fasting volunteers, 400 mL of decaffeinated coffee (equal to 2.5 mmol chlorogenic acid/l) reduces the glycemic index of meals and elevates GLP-1 levels [25]. As shown in Scheme 11.

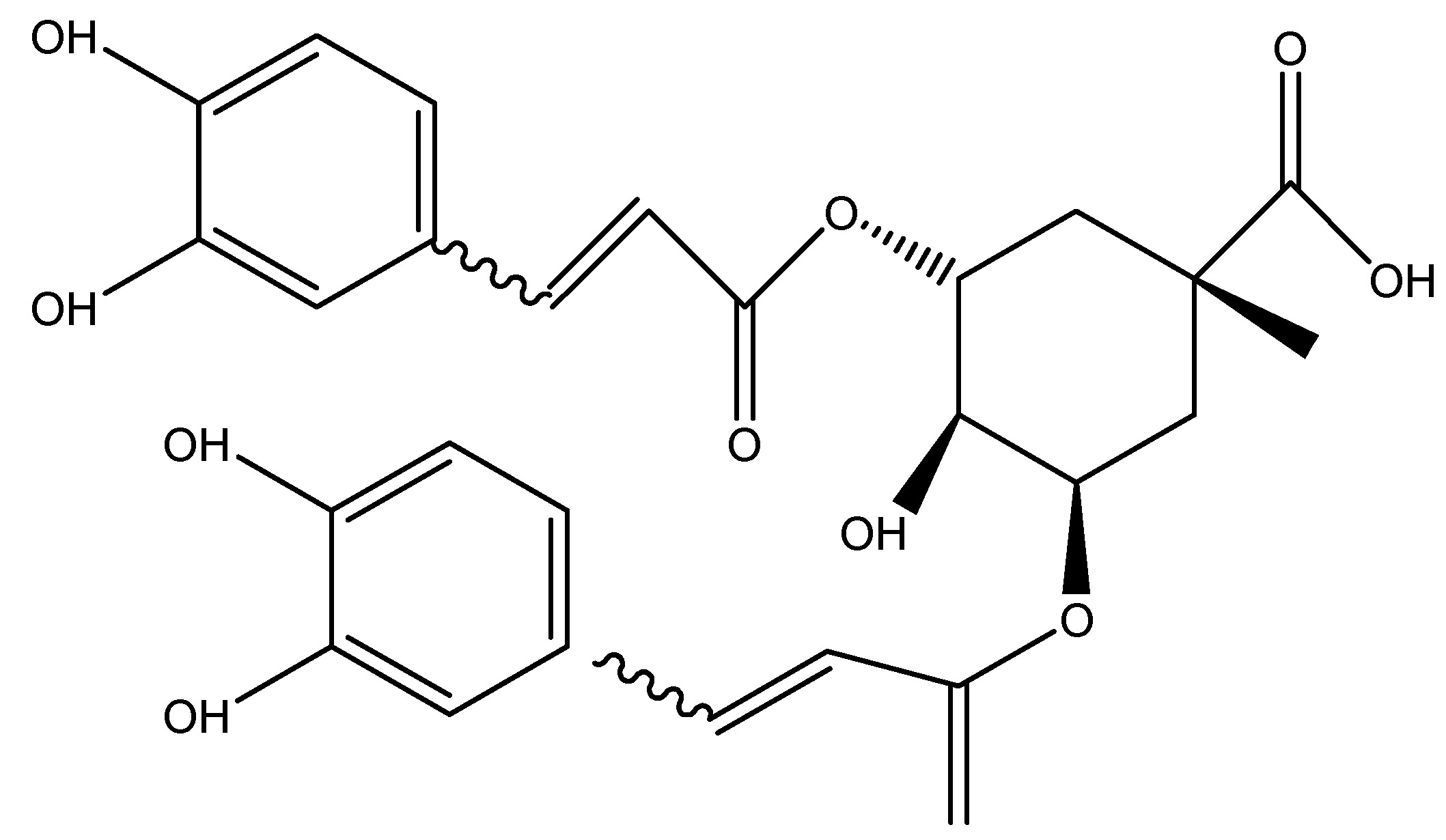

(12) Gardenia

Scientific name—Gardenia jasminoides.

Synonyms—Cape jasmine, Gardenia augusta, and Cape jessamine.

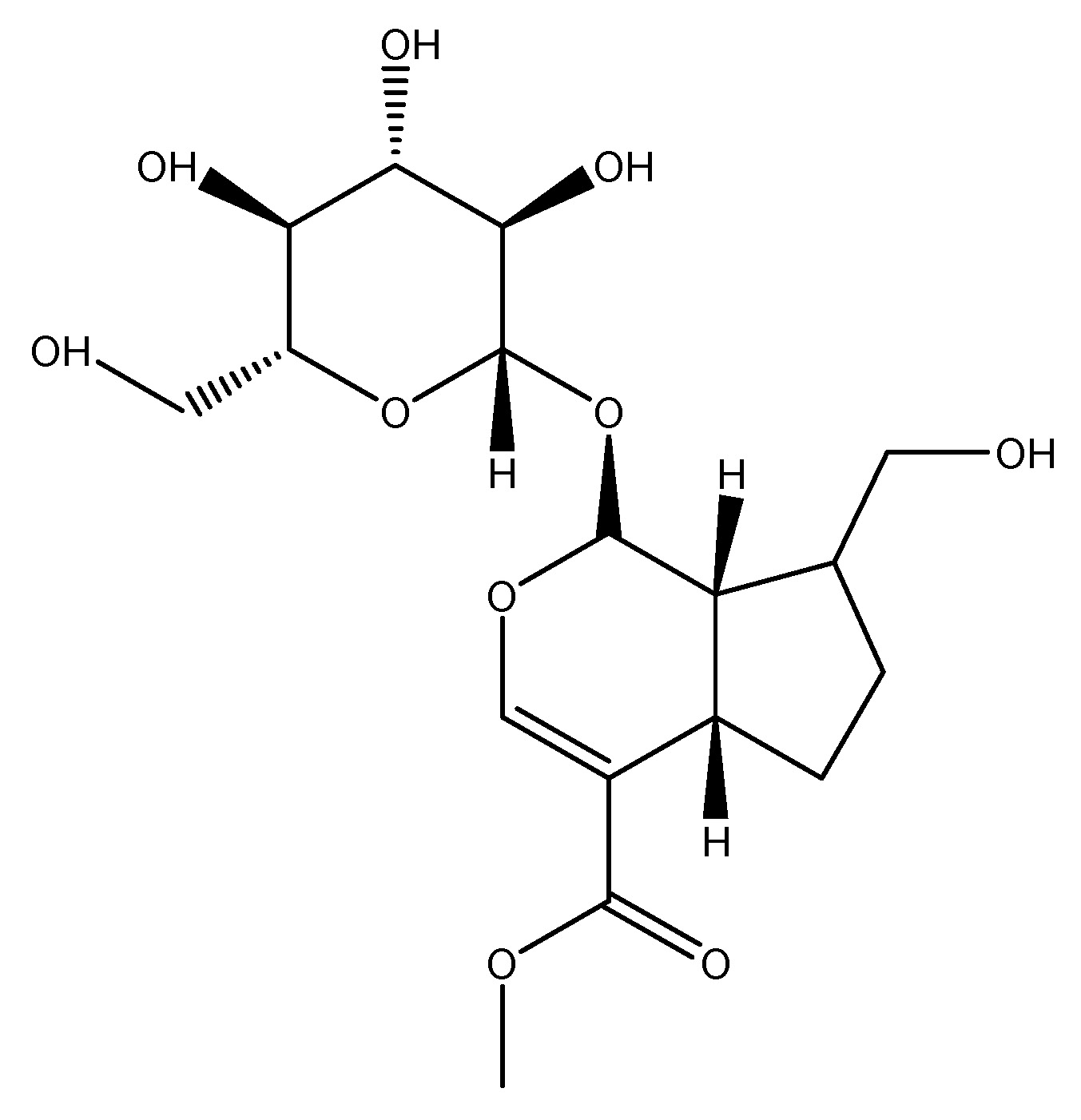

Gardenia is an evergreen flowering plant which belong to the Rubiaceae family, endemic to regions of Southeast Asia. This wild plant’s primary chemical ingredient is Geniposide (GP). The primary component is fruit, which is evidenced by studies indicating that its administration in insulin-secreting cell lines (INS-1 cells) demonstrates that geniposides mitigate oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis and enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by activating the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor [26]. As shown in Scheme 12.

(13) Ginger

Scientific name—Zingiber officinale.

Synonyms—Rhizoma zingiberis, Canton ginger, and Stem ginger.

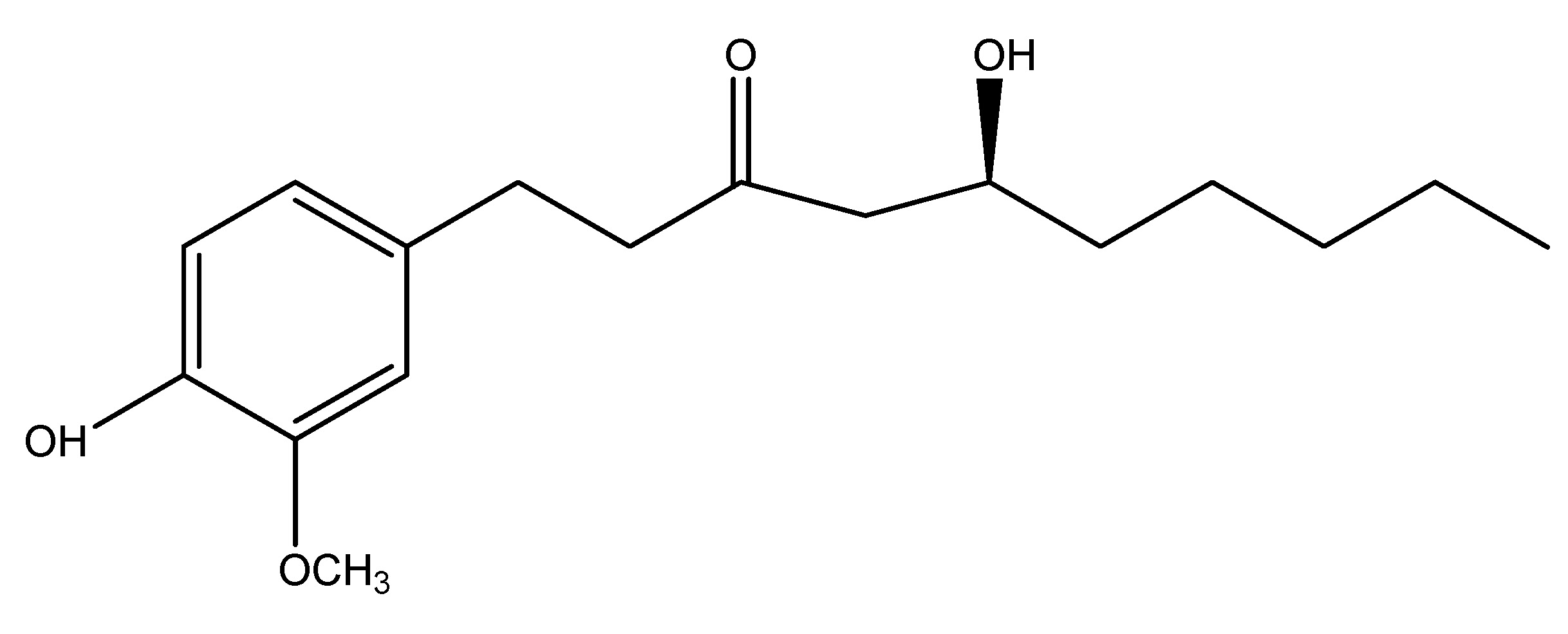

Ginger is a blooming plant and its rhizome and roots are extensively utilized as a spice. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annually & this belongs to the Zingiberaceae family. Mostly located in Southeast Asia, it comprises carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, with its chemical contents including zingiberene, curcumene, and gingerol. The primary active ingredient is gingerol, in studies, it is administered at a dosage of 200 mg/kg to in a diabetic mouse for research purposes, demonstrating activation of GLP-1 and mediation of insulin production [27]. As shown in Scheme 13.

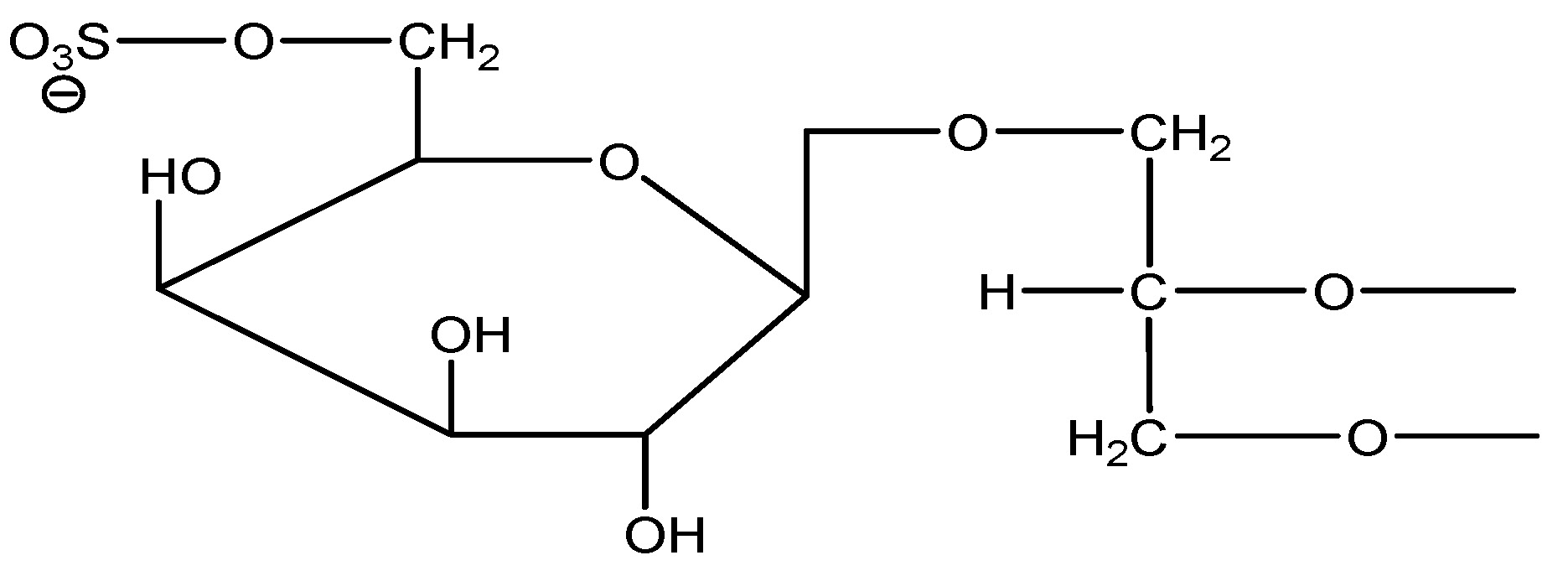

(14) Guar Gum

Scientific name—Cyamopsis tetragonoloba.

Synonyms—Cordaea fabiformis, Dolichos fabiformis, Guar flour, and Meyprofin.

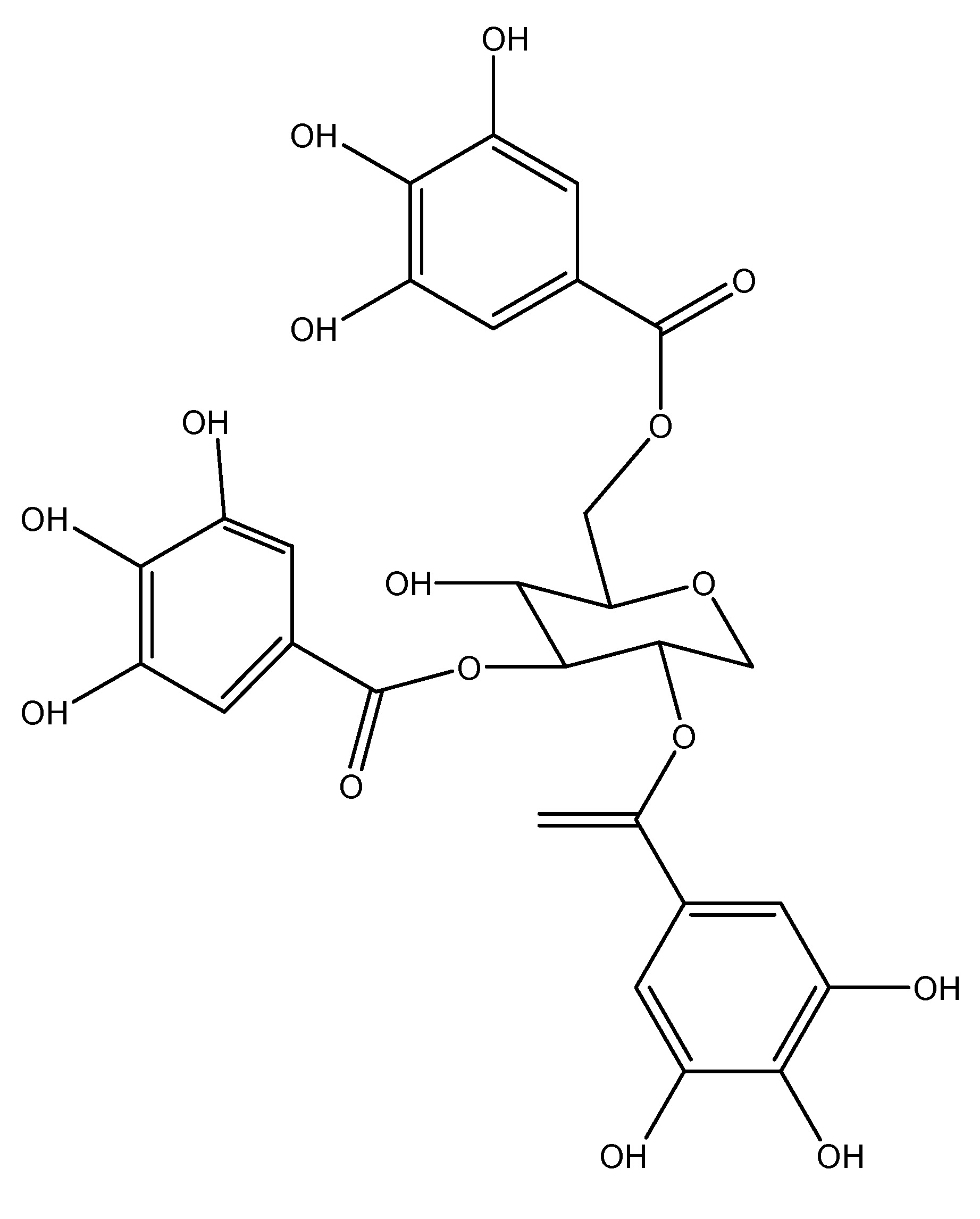

Guar gum, commonly known as guaran or guar bean, Guar Gum is a plant belonging to the Fabaceae family. It is cultivated in South Asia, where rainfall is essential for growth. It comprises a polyphenolic composition that includes gallotannins, gallic acid, and quinic acid. Three models are utilized for the investigations, and their extracts are provided. Initially, a dosage of approximately 20 to 40 mg/kg of guar gum is incorporated into the dietary intake of humans, which diminishes glucose absorption and insulin secretion. Subsequently, a quantity of about 7.6 g per meal of guar gum is administered to diabetic patients, leading to insulinemia. Lastly, a high-fat diet supplemented with 10% guar gum over a duration of 12 weeks is introduced to C57B mice, resulting in the production of short-chain fatty acids through colonic fermentation that stimulate GLP-1 release, thereby enhancing glucose clearance [28]. As shown in Scheme 14.

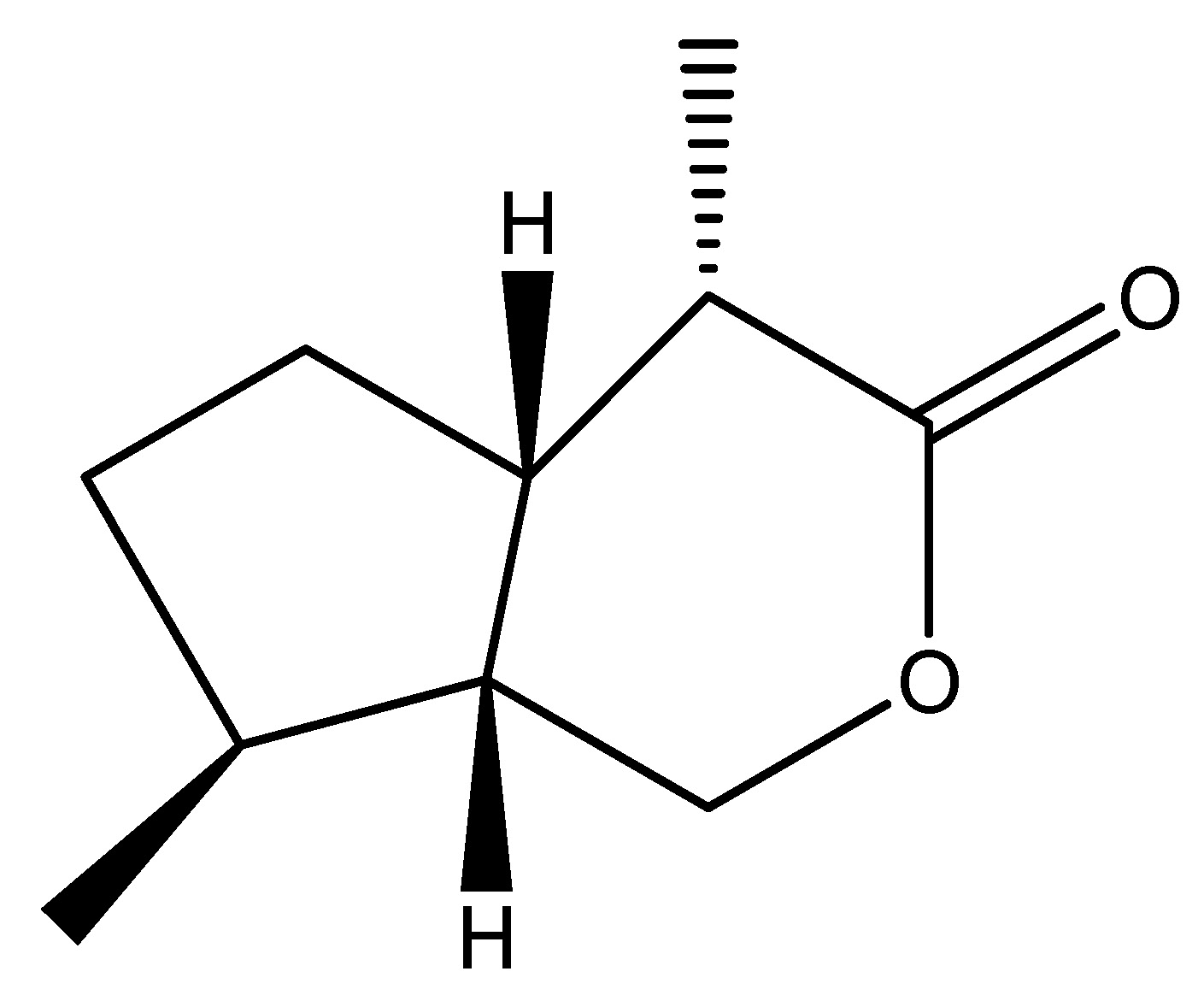

(15) Hoodia Extract

Scientific name—Kalahari cactus.

Synonyms—Bushman’s hat and Hoodia gordonii.

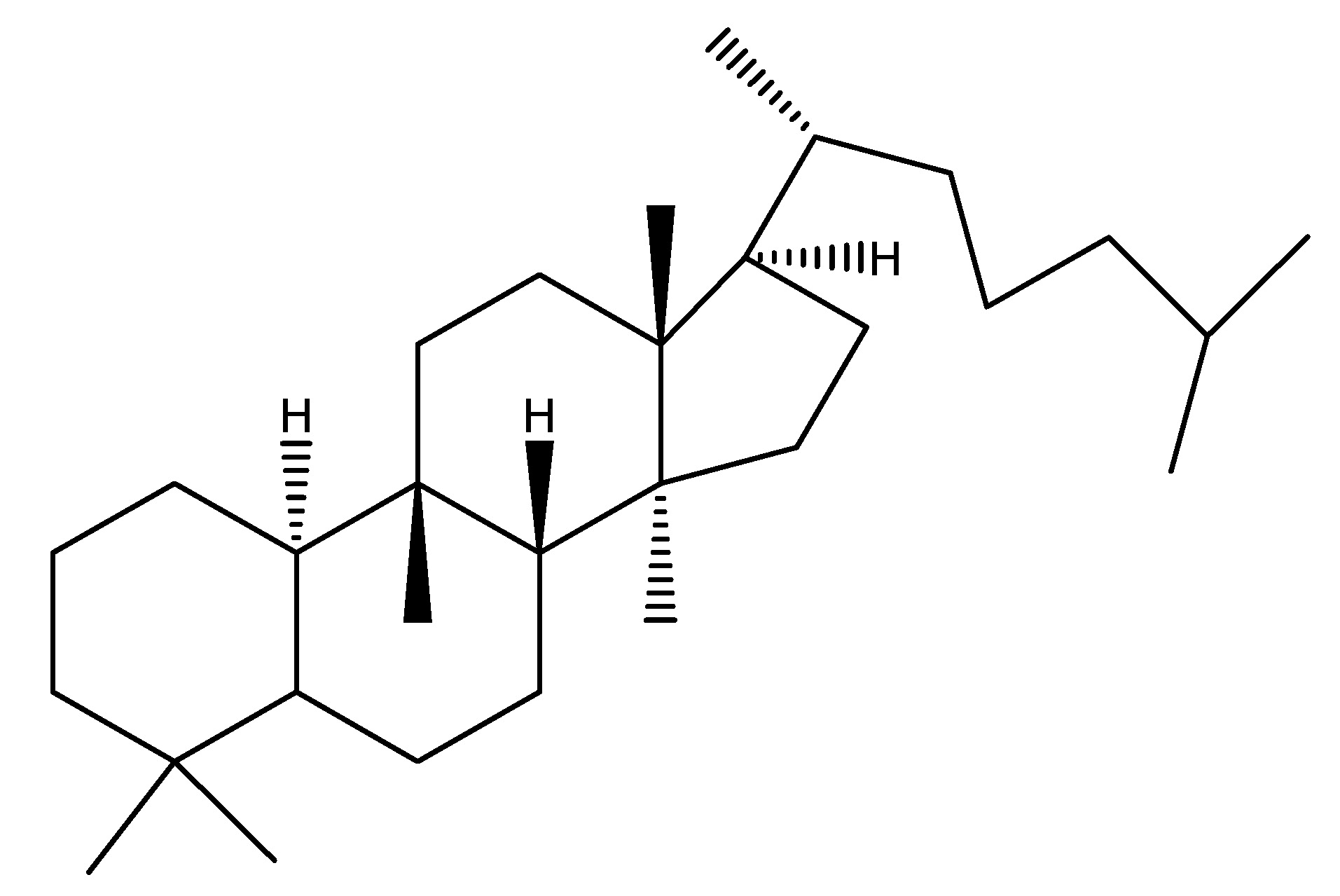

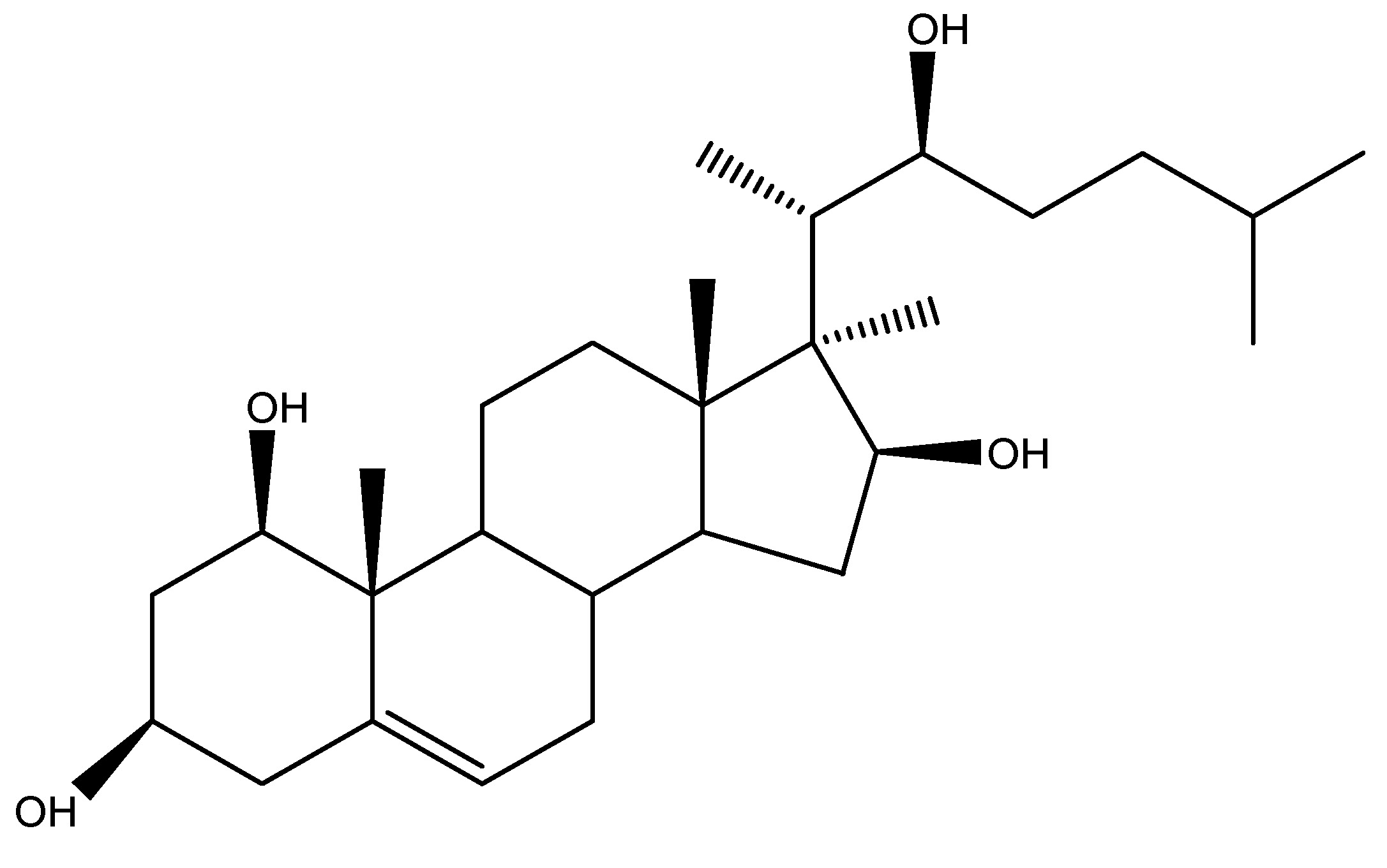

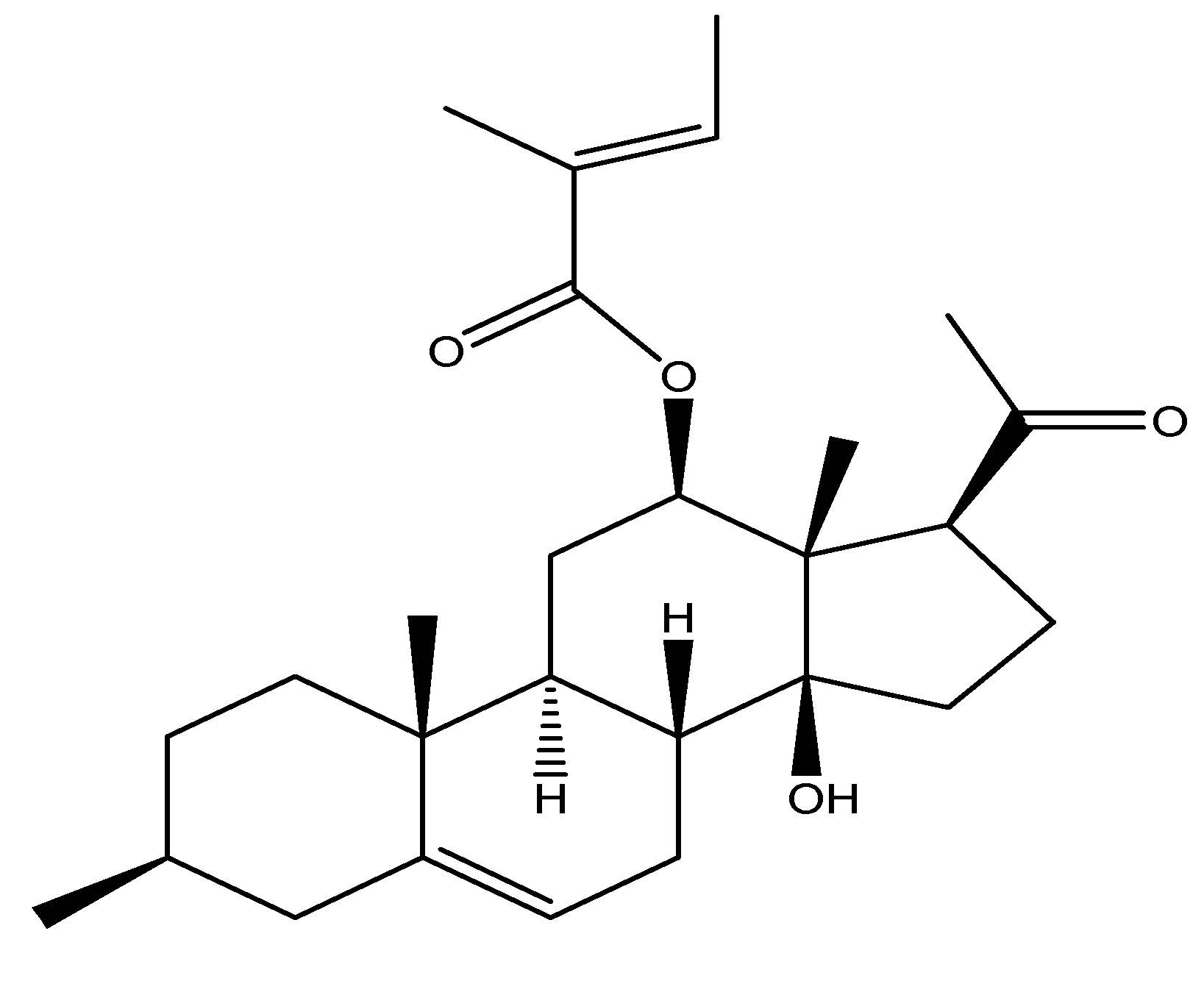

H. Hoodia gordonii is a leafless, prickly succulent plant possess its therapeutic powers in traditional medicine. It naturally occurs in Botswana, South Africa, and Namibia and belongs to the Apocynaceae family and the Hoodia genus. It primarily functions as an appetite suppressor. Gordonosides F is a steroid extracted from the African cactiform Hoodia gordonii, historically utilized by the Xhomani Bushmen as an anorexiant during hunting excursions. Recent investigations involving GPR119 knockout mice demonstrated the oral administration of this H. The extract of Gordonii and its active component, Gordonosides F, promoted glucose-dependent GLP-1 and insulin release, demonstrating a blood glucose-lowering action during the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Hoodia comprises steroid glycosides, fatty acids, plant sterols, and polar chemical compounds. Administering 1000 mg/kg of extract and 200 mg/kg of the active component Gordonosides F in mice resulted in enhanced plasma insulin and plasma GLP-1 production during the OGTT. Isolated rat islets stimulated by GLP-1 have anti-diabetic effects through the activation of GLP-1 receptor agonists [29]. As shown in Scheme 15.

(16) Korean Pine

Scientific name—Pinus koraiensis.

Synonyms—Nana Chinese Pine Nut and P. koraiensis.

Pinus koraiensis, generally referred to as the Korean pine, is a species endemic to eastern Asia, including Korea, northeastern China, and Mongolia, and belongs to the family Pinaceae. This plant is a member of the white pine group, its Pinus section named as Quinquefoliae. The phytochemicals present in these plants are free from fatty acids (FFA) and triglycerides (TG), with the primary component of this plant being the seeds, which are utilized for research purposes. Administration of a 50 µM dose of each free fatty acid from this plant to human females for study revealed that GLP-1 levels were up 60 min after the introduction of pine nuts. It signifies its action as a GLP-1 receptor agonist [30]. As shown in Scheme 16.

(17) Little Dragon

Scientific nomenclature—Artemisia dracunculus L.

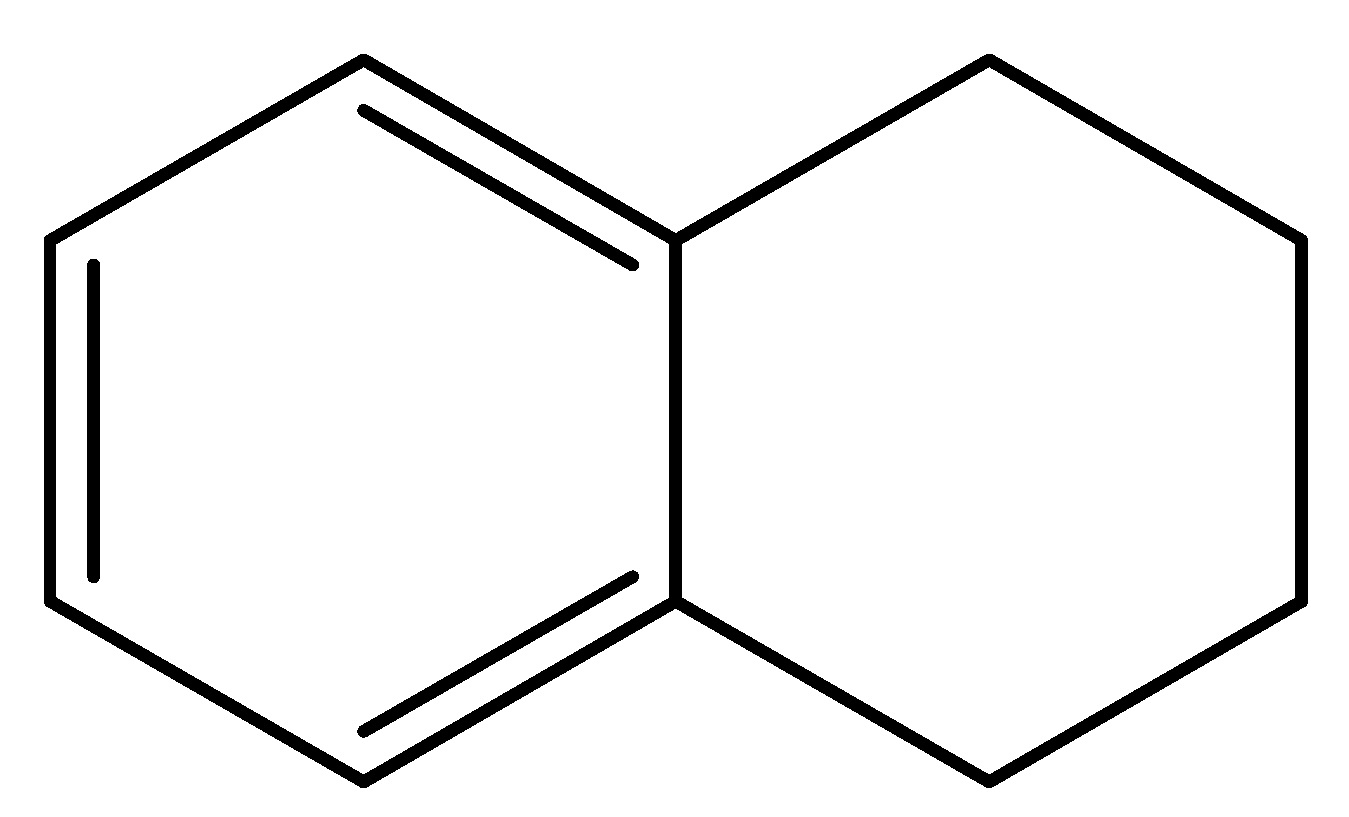

Synonyms—Wild tarragon, Artemisia cernua, Estragon, and Tarragon.

Artemisia dracunculus, commonly referred to as little dragon and it is a perennial herb belonging to the Asteraceae family. It is prevalent in the wild throughout much of North America and Eurasia. The primary component utilized is the leaves of this plant, with Tetralin as the principal chemical constituent. In research administration of 500 mg/kg of Tarralin in a KK-A (gamma mice) resulted in reduced glucose levels and enhanced the binding affinity of Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) to its receptor in vitro. Compared to treatment with established anti-diabetic medications, there were reduced blood glucose levels [31]. As shown in Scheme 17.

(18) Mango

Scientific name—Mangifera indica.

Synonyms—Dicot genus, Mangifera, Mangifera indica, Magnoliopsid genus, and Mangifera amba.

Mangifera indica, usually referred to as mango which is mainly known for its fruit. It is a species of flowering plant belonging to the sumac and Anacardiaceae families. It is believed that this plant is originated from the region including northwestern Myanmar, Bangladesh, and India and is characterized as a huge fruit tree. The primary component of this tree utilized for research purposes. The mango tree possesses nutritional and phytochemical constituents, including macronutrients (which contains carbohydrates, proteins, amino acids, and lipids) as well as leucine, valine, arginine, and fatty acids. The study indicated that a concentration of 320 µg/mL of Mangifera indica used in the in vitro model suppresses DPP-4 and enhances GLP-1 for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [32]. As shown in Scheme 18.

(19) Mate Tea

Scientific name—Ilex paraguariensis.

Synonyms—Yerba mate, Guarani, and Erva-mate.

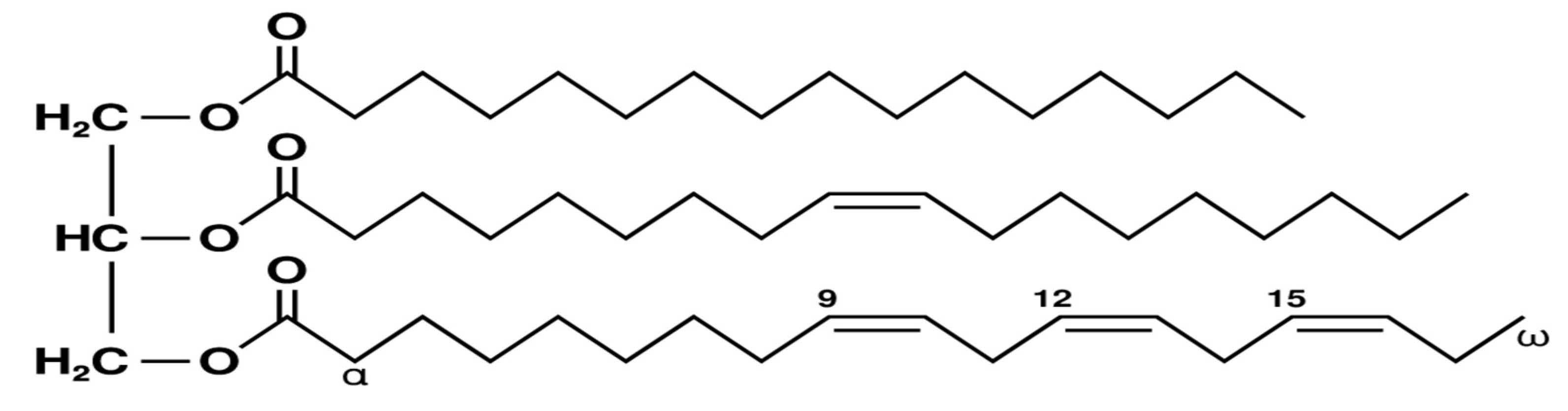

Mate tea is a species of the holly genus of the Aquifoliaceae family, native to South America. It was identified by the French botanist Augustin Saint-Hilaire and its aqueous extract is derived from the leaves of plant. The chemical constituents of this plant are matesaponin, 3,5-O-dicaffeoyl-d-quinic acid, and matesaponin-2. Administration of 50 and 100 mg/kg/day of the medication in a male mice demonstrated an effect on GLP-1, while acute administration of the primary ingredients of mate resulted in considerable elevations in GLP-1 levels. Compounds (3,5-Odicaffeoyl-d-quinic acid and matesaponin-2 and linolenic acid exhibited significant elevations in GLP-1 levels [33]. As shown in Scheme 19.

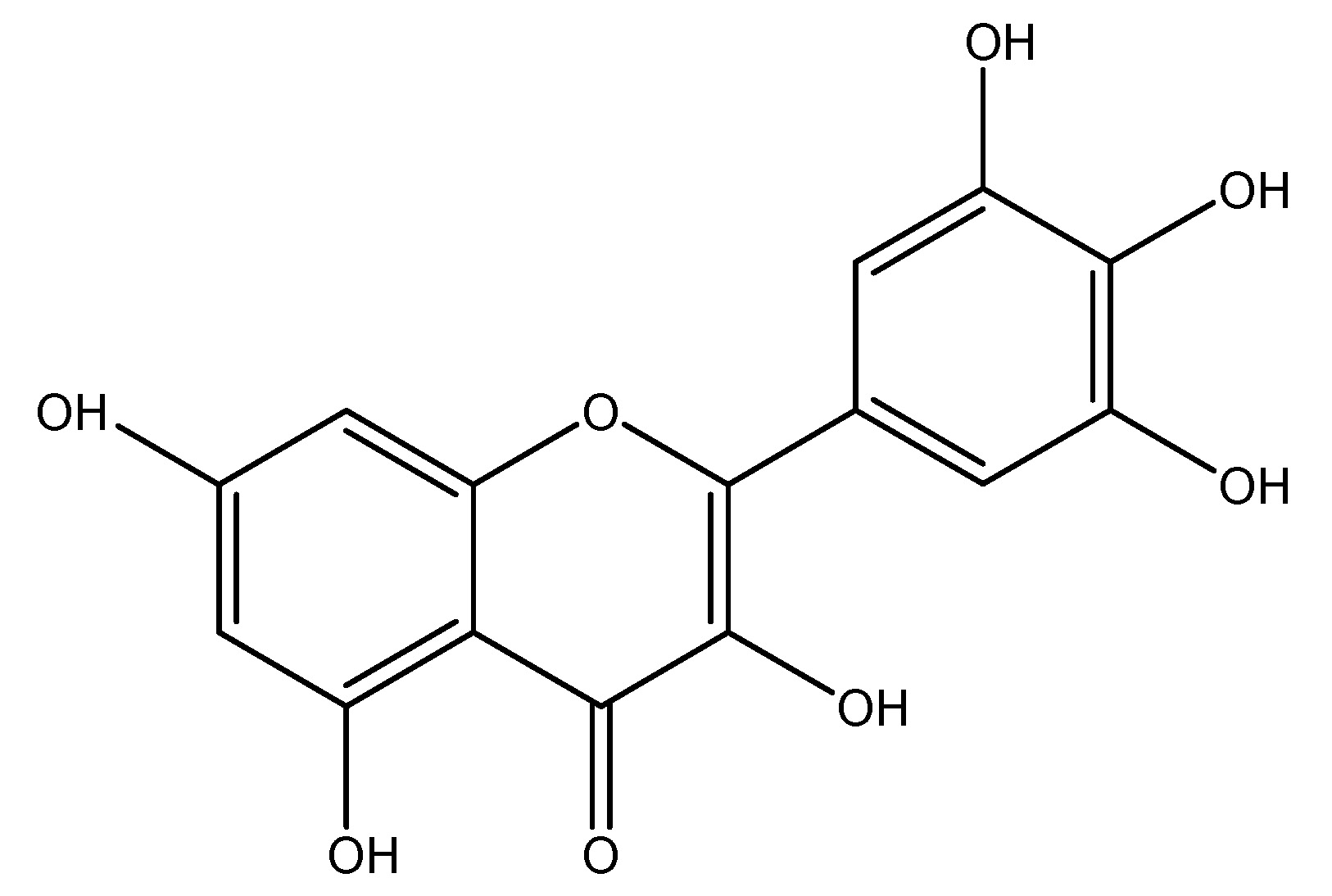

(20) Myricetin

Scientific name—Myrica rubra.

Synonyms—Cannabiscetin, Myricetol, and Myricitin.

Evidence indicates that myricetin plant possesses anti-diabetic properties, which are mediated through the regulation of glucose transport via glucose transporter. Myricetin functions as a glucose-dependent insulin secretagogue, akin to GLP-1 and includes the inhibition of beta cell apoptosis, glucoregulation and the prevention of hypoglycemia. This plant is belonging to the Myricaceae family. It is a flavonoid derived from the leaves of Myrica rubra, comprising protein, polyphenols, arabinose, and myricetinin as its chemical constituents. Subcutaneous injections of 250 µg/kg body weight were delivered into the male wistar rats, resulting in an insulin secretion assay that demonstrates anti-diabetic characteristics through the activation of GLP-1 receptor agonists. In human tests, an oral dosage of 250 µg/kg body weight resulted in a reduction of two injections per day [34]. As shown in Scheme 20.

(21) Olive Oil

Scientific name—Olea europaea L.

Synonyms—Indian olive, Olea ferruginea, and Mature fruit.

Olive oil is a fixed oil extracted from the ripe fruits of Olea europaea it is a member of the Oleaceae family. This is a conventional tree crop of the mediterranean region and obtained by pressing whole olives to extract the oil. The content of olive oil fluctuates based on the harvest period and extraction method. It mostly comprises oleic acid, palmitic acid, linoleic acid and monounsaturated fatty acids, with oligofructose as the active component. This mostly modulates GLP-1 homeostasis through the action of a GLP-1 receptor agonist [31].

(22) Phlomoides rotata

Biological origin—Phlomoides rotata.

Synonyms—Jerusalem sage, Lampwick plant, and Phlomoides.

This is a flowering plant from the Lamiaceae family, native to the Mediterranean region and extending eastward across Central Asia to China. This herb is utilized as a traditional restorative remedy for tuberculosis, respiratory conditions, cardiovascular diseases and rheumatoid arthritis. The chemical constituents of this plant are luteolin, isoorientin, and chlorogenic acid. The administered active compound is Shanzhiside methylester, utilized in Wistar rats for allodynia testing at concentrations of 10, 30, 100, and 300 µg intrathecally, functioning as a GLP-1 receptor agonist [11]. As shown in Scheme 21.

(23) Plantago indica

Scientific nomenclature—Plantago indica.

Synonyms—Plantago major, Plantago lanceolata, Plantago psyllium, and Plantago arenaria.

Plantago indica is a flowering plant belonging to the Plantaginaceae family, indigenous to regions of Africa, Europe, Russia, and Asia. Primarily located in arid inland regions, this plant is not widely utilized as a food source; nonetheless, it has been cultivated for its seeds, which possess medical properties as a laxative. This plant has several potent chemical ingredients, including flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolic acid derivatives, and iridoid glycosides which contribute to its particular therapeutic effects. In trials, a fiber-enriched breakfast of 23 g is administered to healthy young individuals, resulting in decreased glycemia and increased postprandial GLP-1 levels [29]. As shown in Scheme 22.

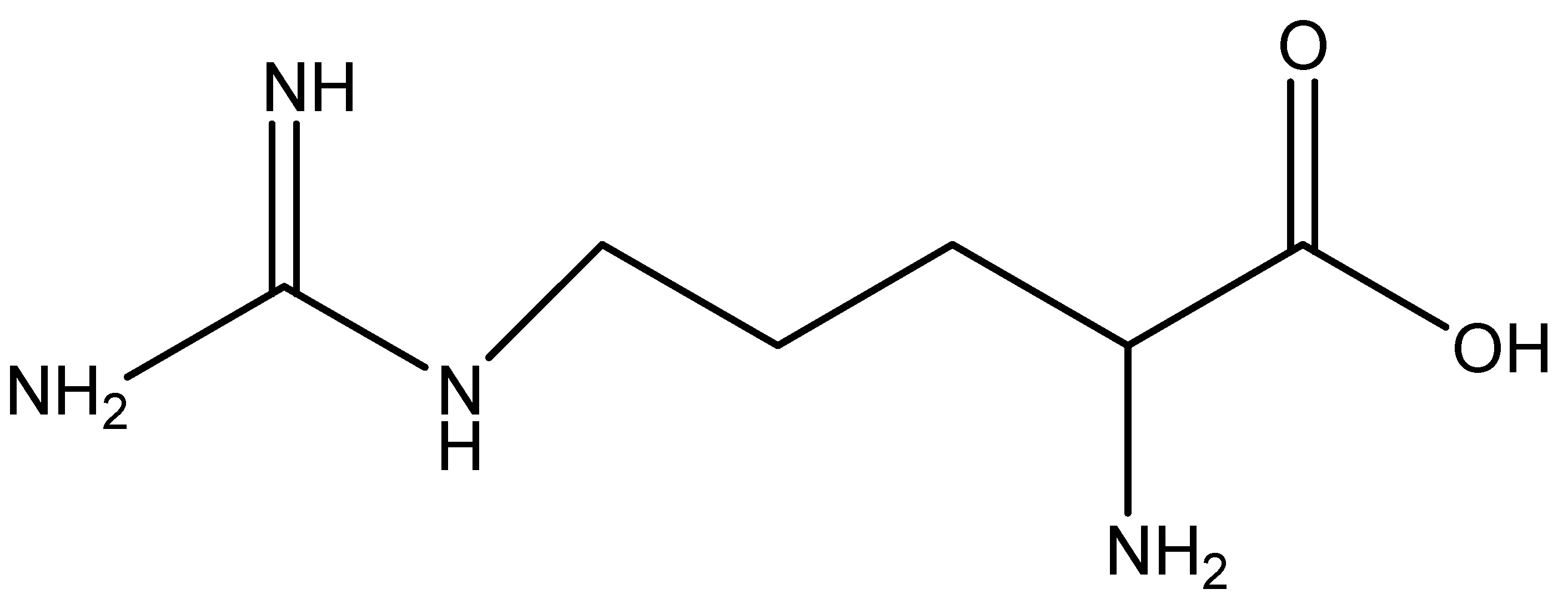

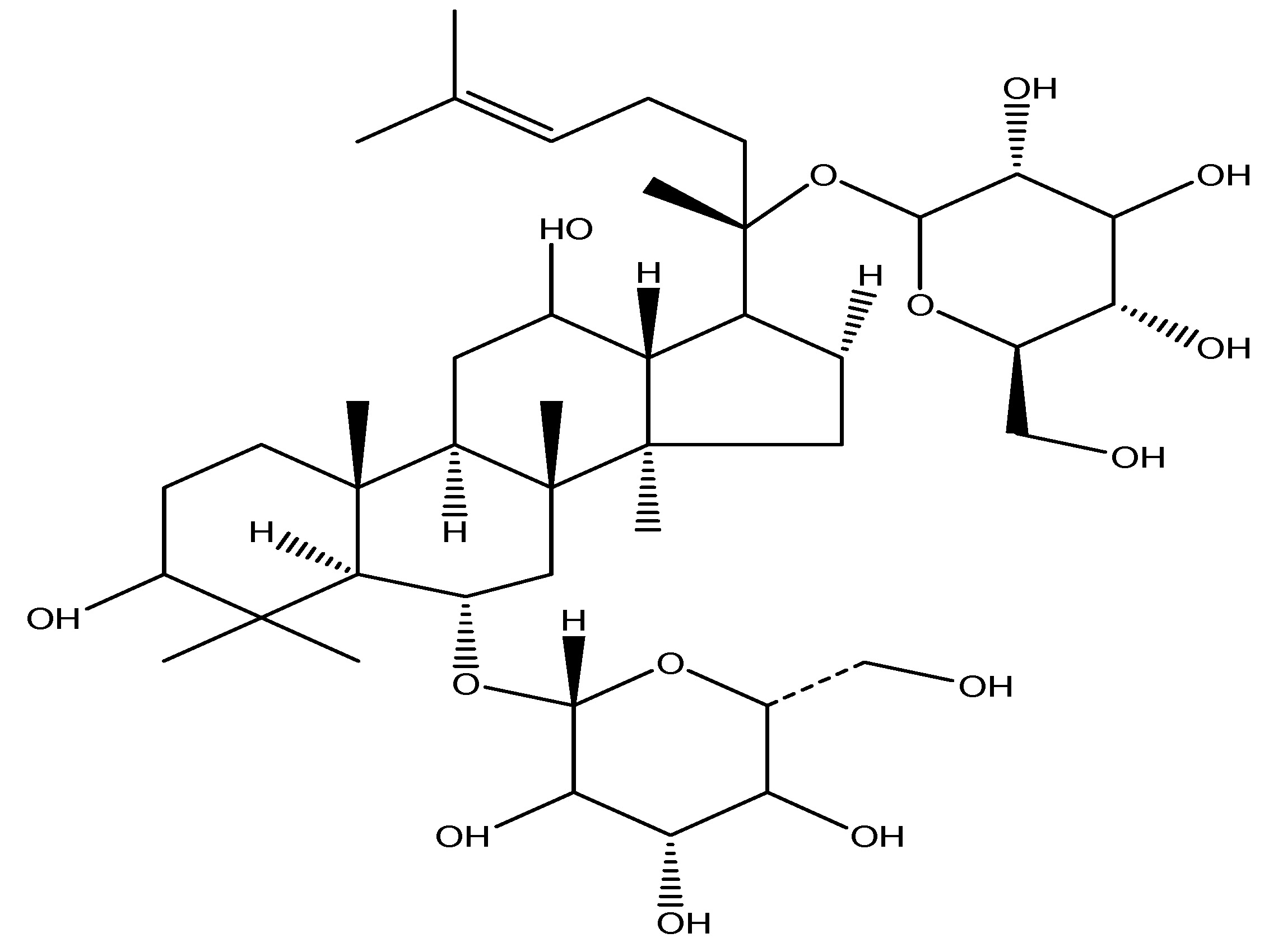

(24) Panax Ginseng

Scientific name—Panax ginseng.

Synonyms—Korean Ginseng, Herbal Ginseng, and South Chinese Ginseng.

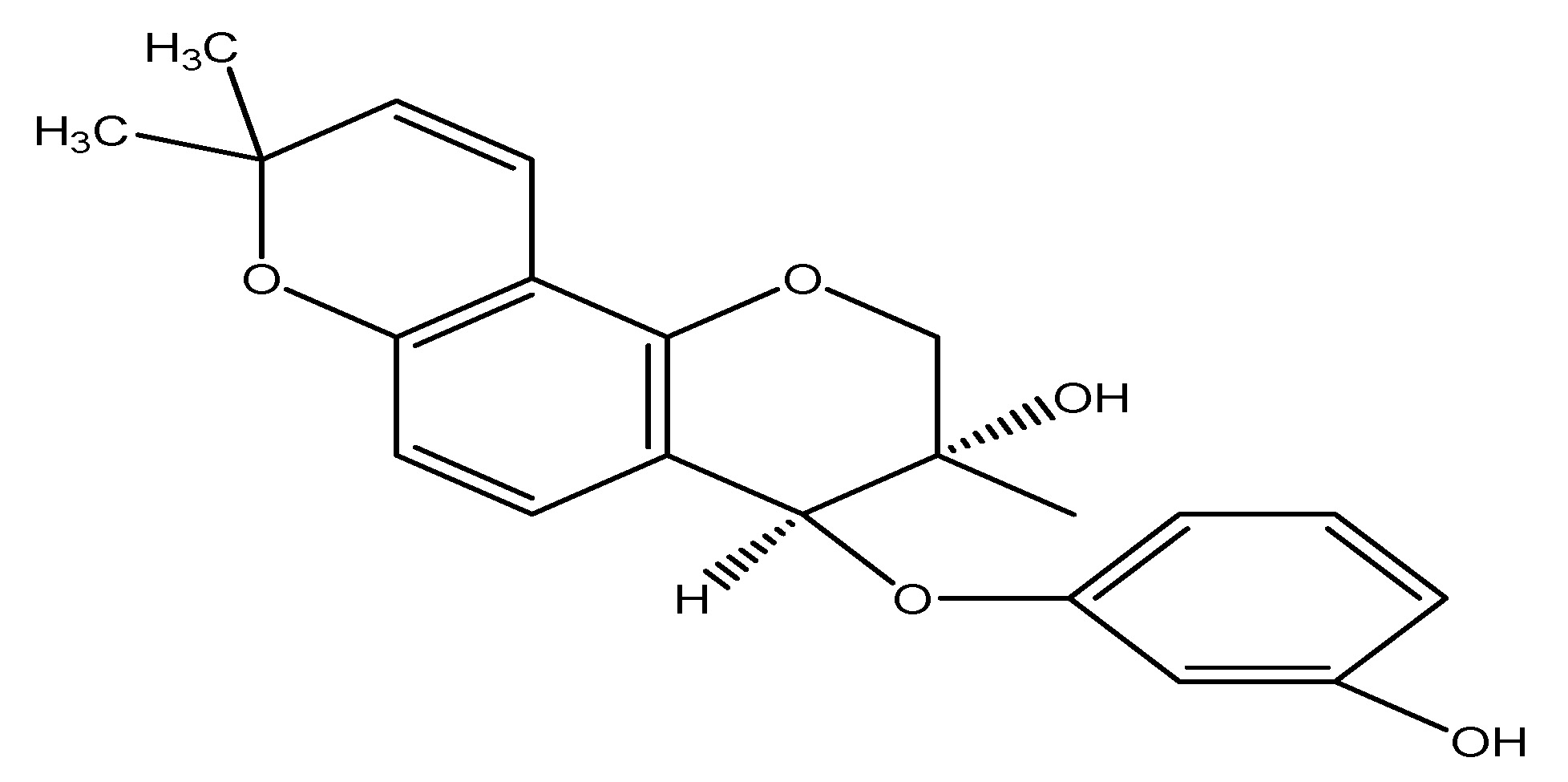

Panax ginseng is a plant whose root is the primary source of ginseng and belongs to the Araliaceae family. It interacts with sweet taste receptors present in enteroendocrine L cells. When it is used for In -vitro investigations utilizing human and murine enteroendocrine cells indicated that this stimulates GLP-1 production. It is a dietary supplement. Numerous ginsenoids including Rb1, Rb2, Re, C-K and Rg3 have been documented to exhibit anti-diabetic and anti-obesity properties. Panax Ginseng is rich in ginsenosides, triterpenoids, gintonin and saponins. Prolonged intraperitoneal administration of Rb1 (10 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction in food consumption and body mass, and demonstrated an impact on a GLP-1 receptor agonists. Intraperitoneal administration of Re (20 mg/kg) for 12 days decreased fasting blood glucose levels in ob/ob mice [32]. As shown in Scheme 23.

(25) Pomelo

Scientific name—Citrus maxima.

Synonyms—Pummelo, Shaddock, Citrus grandis, and Citrus decumana.

Citrus maxima, often known as pomelo, is the largest citrus fruit belonging to the Rutaceae family and serves as the primary ancestor of the grapefruit. It is a native, non-hybrid citrus fruit originating from Southeast Asia. The extract of dried fruit of this is utilized for investigations on its chemical contents which include Naringenin, Osthol and DDPH. Seventy percent ethanol extract was provided at doses of 300, 600 and 1200 mg/kg to genetically obese in Zucker rats resulting in a reduction of circulating GLP-1 by acting on GLP-1 receptors [32]. As shown in Scheme 24.

(26) Pygeum

Scientific name—Prunus Africana.

Synonyms—Ironwood, African cherry, Stinkwood, and Bitter almond.

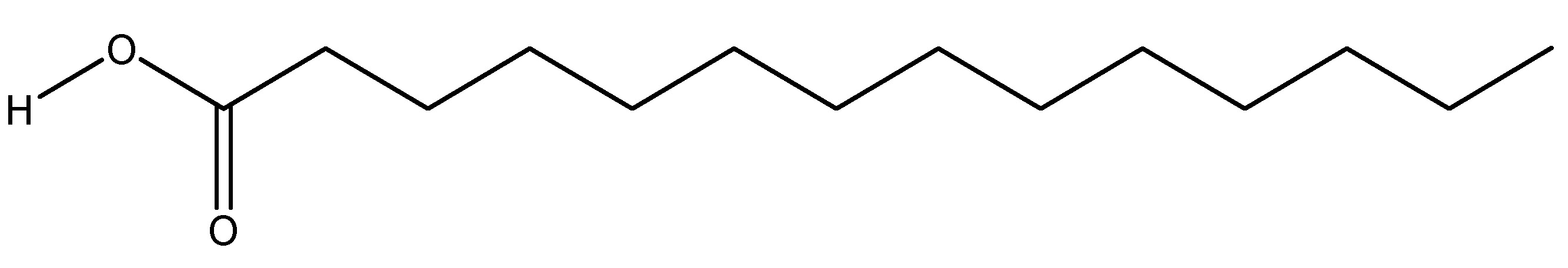

Pygeum is widely distributed over Africa, particularly in the mountainous regions of central and southern Africa, and belongs to the Rosaceae family. The primary component utilized in research is the bark. The chemical constituents include lauric acid, myristic acid, sitostenone, sitosterol, and ursolic acid. This is utilized in traditional medicine to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia. Doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg of this are administered into the Wistar rats. Which indicates this plant enhances insulin secretion by reducing DPP-4 activity, hence prolonging the half-life of GLP-1 [30]. As shown in Scheme 25.

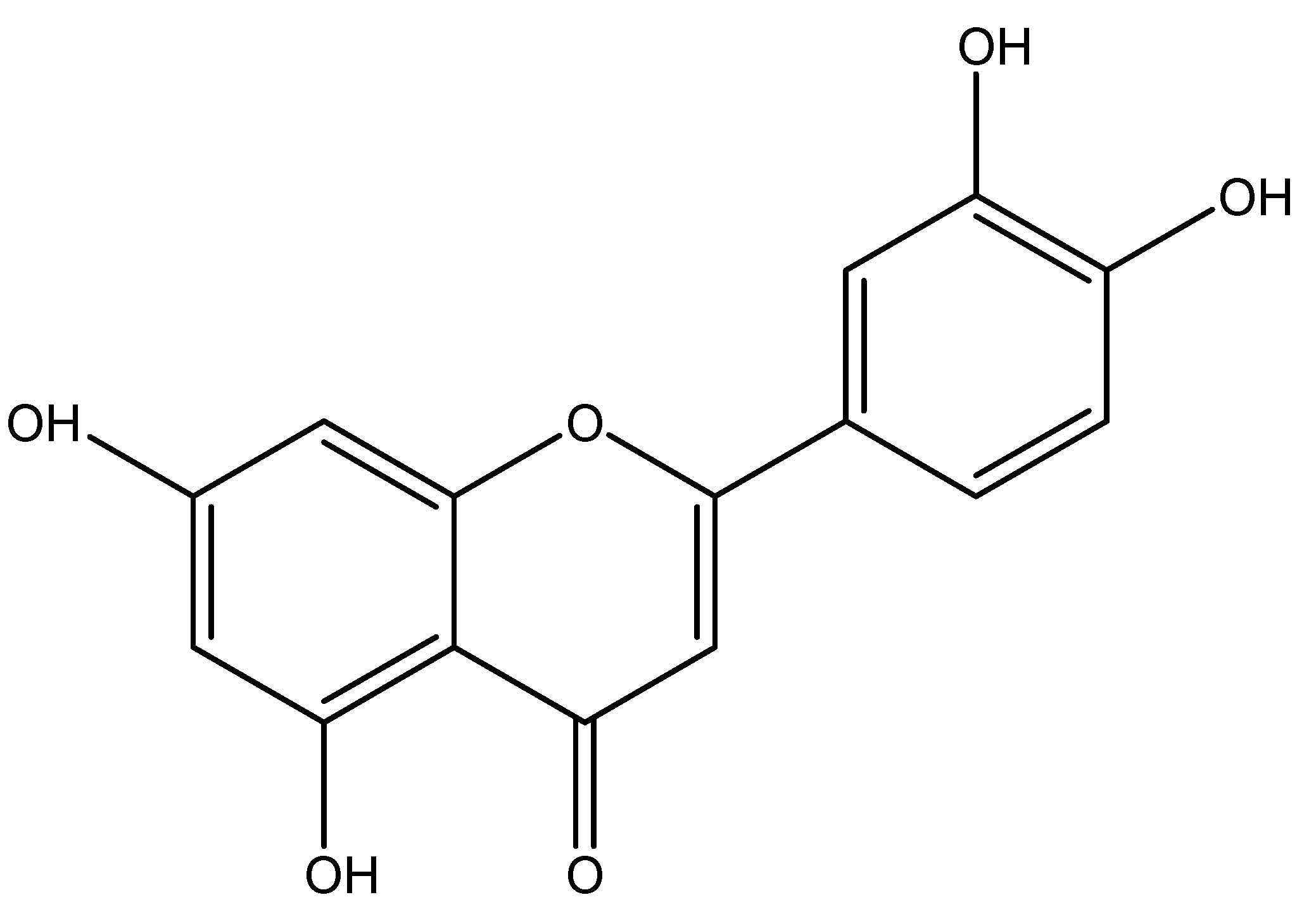

(27) Quercetin

Scientific name—Quercus.

Synonyms—Quercetin, Xanthaurine, Quercitol, and Quertine.

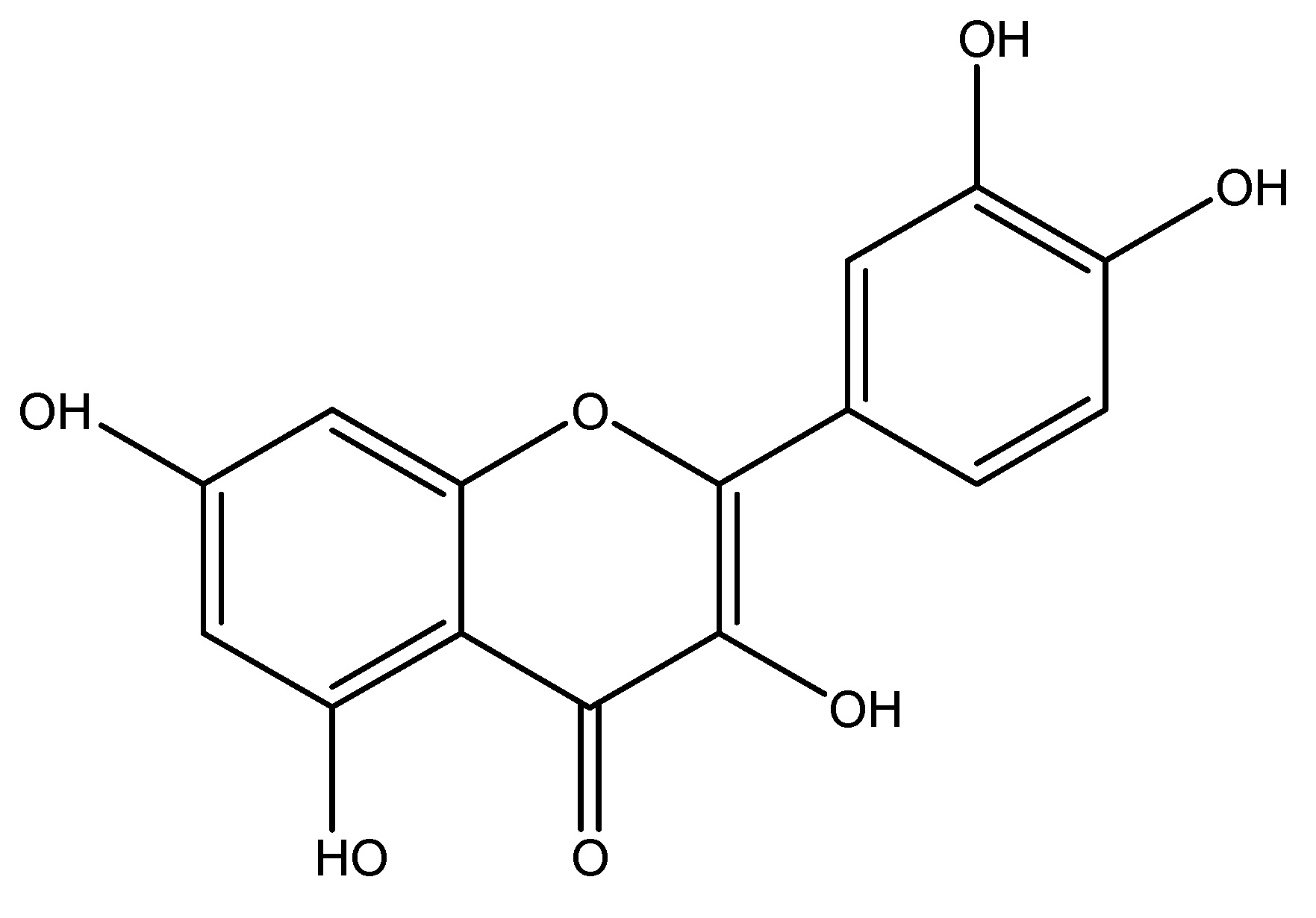

Quercetin is a typical flavonoid that exhibits biochemical and physiological effects, including anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic characteristics. Quercetin is a flavonol, a type of plant pigment belonging to the flavonoid which is a group of polyphenols, predominantly found in fruits, vegetables, leaves and seeds. Quercetin belongs to the family Quercaceae. It exhibits bitterness and reduces blood glucose and urinary sugar levels when administered via IV injections of STZ at 40 mg/kg in Wistar rats, demonstrating anti-diabetic effects through GLP-1 receptor activity. Intraperitoneal injections having doses of 10–15 mg/kg/day for two weeks in people exhibit features analogous to those observed in animal models [31]. As shown in Scheme 26.

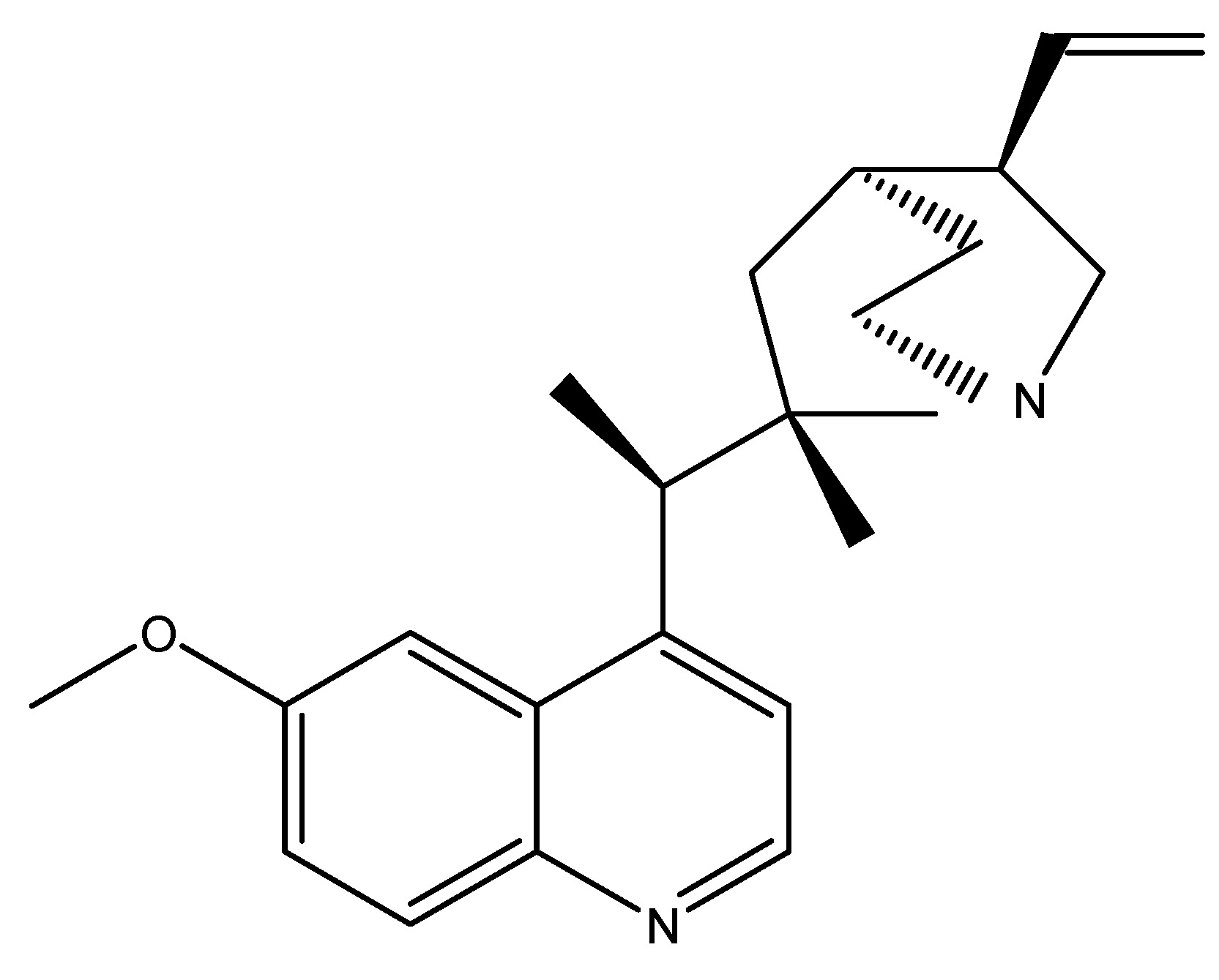

(28) Quinine

Scientific name—Cinchona calisaya.

Synonyms—Colchicine, Hyoscine, Scopolamine, and Strychnine.

Quinine induces GLP-1 secretion in human enteroendocrine NCI-H716 cells. Which is similar to the bitter taste receptor agonist called denatonium, representing a unique class of GLP-1 secretagogues that do not provoke nausea or aversive sensations on the tongue. Quinine is a naturally occurring white crystalline alkaloid found in the bark of the cinchona tree, which belongs to the Rubiaceae family. A recent study has shown that bitter taste receptors are utilized in the treatment of humans, namely in the NCI-H716 cell line. Quinine is an alkaloid medication that primarily consists of the chemical constituent’s quinidine, quinine, and cinchonine. Evidence indicates that it possesses antidiabetic characteristics via functioning as a GLP-1 receptor agonist on human L cell lines [33]. As shown in Scheme 27.

(29) Scabra

Scientific name—Gentiana scabra.

Synonyms—Dasystephana scabra (Bunge), Japanese gentian, Gentiana fortune Hook.

Gentiana scabra qualifies as a bitter-tasting medicinal plant, and its root extracts have a GLP-1 secreting action in humans; it belongs to the Gentianaceae family. The chemical ingredients include Secoiritoid glycosides, amarogentin, and gentiopicrin, which are responsible for the bitter flavor. Scabra is a medicinal herb utilized for the treatment of “sogal,” which shares a similar pathology with diabetes mellitus (DM). Gentiana Scabra root extracts induce GLP-1 secretion in human cells via a G-protein subunit-mediated route, resulting in the release of GLP-1 and insulin, which mitigate hyperglycemic condition in a type 2 diabetes mice model. Research on a human model indicated that Scabra extracts (100 mg/kg) reduced glucose levels in db/db mice during the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) while plasma GLP-1 and insulin levels significantly rose 10 min post-administration [33]. As shown in Scheme 28.

(30) Sour Orange

Scientific name—Citrus aurantium.

Synonyms—Seville orange, Bitter orange, Bigarade orange, and Aurantium acre mill.

Sour orange is a citrus species have traditionally been utilized as medicinal herbs within the Rutaceae family in Eastern cultures. A recent study indicates that a novel oriental herbal medication demonstrates efficacy in treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. It comprises flavonoids, glycosides, and alkaloids. Recent studies on Citrus aurantium indicate that the hexane fraction of CA (HFCA) stimulates NCI-H716 cells and induces membrane depolarization in NCI-H716, resulting in the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which regulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. GLP-1 has been utilized in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). The chemical ingredients are apigenin and luteolin. This was also a study conducted on the Human L cell line [34]. As shown in Scheme 29.

(31) Soybean

Scientific name—Glycine max.

Synonyms—Soybean, soy, and soja bean.

The soybean is a leguminous plant indigenous to East Asia, extensively cultivated for its edible seeds with several applications. This plant belongs to the Fabaceae family and its roots function as GLP-1 receptor agonists. The primary phytochemical constituents of Glycine max are glyceollins, delivered at a dosage of 20 mg/kg in diabetic mice. Glyceollins also enhanced GLP-1.

Secretion to augment insulinotropic effects in enteroendocrine cells. In conclusion, glyceollins function as GLP-1 receptor agonists and may also aid in the prevention of prostate cancer in women [34]. As shown in Scheme 30.

(32) Sweet Potato

Scientific nomenclature—Ipomoea batatas.

Synonyms—Ipomoea edulis and Ipomoea vulvus.

The sweet potato is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the Convolvulaceae family, which is also known as bindweed or morning glory. It possesses big, starchy, and sweet-tasting tuberous roots utilized as a root vegetable. They mostly constitute North America, and their nutrient composition includes carbs, fats, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. The primary chemical constituents of Ipomoea batatas include myristic acid, tetracosane, beta-carotene, and daucosterol. The leaf extract and quinic acid derivatives are utilized in experiments, administering 10 mg/mL of extract components and 10 mM to diabetic mice GLUTag cells, resulting in reduced glycemia and increased GLP-1 production [19]. As shown in Scheme 31.

(33) Vitis vinifera

Scientific name—Vitis vinifera.

Synonyms—Muscadine, Genus Vitis, Vitis vinifera, Common grapevine, and Grape.

The common grape vine is a flowering plant species indigenous to southwestern Asia, Morocco, and Portugal. This plant belongs to the Vitaceae family and it is utilized to manufacture wine, vinegar, or juice, and is dried to create raisins. The primary chemical ingredients are phenolic chemicals, stilbenoids, and anthocyanins. The active component Procyanidins is administered to Wistar rats at a dose of 500 mg/kg for research purposes, resulting in an increase in plasma GLP-1 levels in rats [19]. As shown in Scheme 32.

(34) Wheat

Scientific name—Triticum aestivum.

Synonyms—Gluten, Semolina, Spelt, Durum, and Triticum vulgare.

Wheat, also referred to as bread wheat, is a cultivated species that constitutes approximately 95% of global wheat production, yielding the highest monetary returns among crops. It belongs to the Poaceae family, with its primary component being fibers, which contain chemical constituents such as glycolipids and phenolic compounds. Studies conducted on humans indicate a dosage of 24 g per day. Augmenting wheat fiber consumption requires several months but ultimately leads to enhanced production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This is referenced in Ayurveda as a herbal medicinal method, detailing the diseases of kapha and pitta [35]. As shown in Scheme 33.

4. Impact of GLP-1 on Obesity

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, initially designed for type 2 diabetes (T2D), have emerged as a revolutionary treatment for obesity owing to their significant impact on weight reduction and metabolic control. These medicines augment glucose-dependent insulin secretion, inhibit glucagon release, and prolong gastric emptying; nevertheless, their most pronounced effect in obesity is appetite reduction through central nervous system (CNS) mechanisms, mainly within the hypothalamus [35]. Semaglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 agonist, exhibited a sustained weight decrease of approximately 15% of body weight in clinical studies, whereas tirzepatide, a combination GIP/GLP-1 agonist, attained a weight loss of up to 22.5% in the SURMOUNT trials [36,37]. In addition to weight loss, GLP-1 agonists enhance cardiometabolic risk factors by decreasing visceral fat, blood pressure, and inflammation [38]. Nonetheless, gastrointestinal adverse symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting) persist often, and long-term safety data are still being examined. Due to their effectiveness, GLP-1-based medicines have become fundamental in obesity pharmacotherapy, with current investigations into next-generation multi-agonists (e.g., retatrutide) aimed at improving results [39].

Trails

The quantity of clinical trials examining the benefits of medical plant extracts or natural products is notably small and has shown minimal efficacy. A study evaluated a rose hip fruit extract (40 g for 6 weeks) in a randomized, double-blind, crossover design involving 31 obese participants with normal or reduced glucose tolerance; however, the extract did not influence incretin levels [40]. As shown in Table 1.

Comprehensive table summarizing plant-derived GLP-1 agonists with their key characteristics.

|

S.NO |

Plant Name |

Scientific Name |

Active Constituents |

Mechanism of Action |

Dosage/Model Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Agave |

Agave tequilana |

Fructans |

Stimulates GLP-1 production in colon. |

10% fructans in C57BL/6J mice. |

|

2 |

Berberis (Barberry) |

Berberis vulgaris |

Berberine |

↑ GLP-1, ↑ GLUT-4, enhances glycolysis. |

500 mg/kg in rats. |

|

3 |

Bitter Hop |

Humulus lupulus |

Humulone, Lupulone |

Bitter taste receptors → ↑ GLP-1 secretion. |

Human L-cell studies. |

|

4 |

Bitter Melon (Karela) |

Momordica charantia |

Karavilagenine E |

↑ GLP-1 & insulin, ↓ glucose. |

5000 mg/kg in mice. |

|

5 |

Black Chokeberry |

Aronia melanocarpa |

Cyanidin 3,5-diglucoside |

DPP-4 inhibition → ↑ GLP-1. |

IC50 5.5 µM (in vitro). |

|

6 |

Black Currant |

Ribes nigrum |

Delphinidin 3-rutinoside |

Enhances GLP-1 & insulin secretion. |

5 mg/kg in GLUTag cells. |

|

7 |

China Mongolia |

Anemarrhena asphodeloides |

Steroidal saponins |

↑ GLP-1 secretion via L-cells. |

Human L-cell line studies. |

|

8 |

Chinese Throughwax |

Bupleurum falcatum |

Saponins, Coumarins |

G-protein-mediated ↑ GLP-1 secretion. |

100–500 µg/mL in NCI-H716 cells. |

|

9 |

Chinese Yam |

Dioscorea polystachya |

Allantoin |

↑ GLP-1 release. |

2 mg/kg in STZ-treated rats. |

|

10 |

Cinnamon Tree |

Cinnamomum zeylanicum |

Cinnamaldehyde |

↑ GLP-1, ↓ insulin resistance. |

3 g in humans (post-meal). |

|

11 |

Coffee |

Coffea arabica |

Chlorogenic acid |

Modulates GLP-1 secretion. |

400 mL decaf coffee in humans. |

|

12 |

Gardenia |

Gardenia jasminoides |

Geniposide (GP) |

Activates GLP-1 receptor → ↑ insulin. |

INS-1 cell line studies. |

|

13 |

Ginger |

Zingiber officinale |

Gingerol |

Activates GLP-1 → ↑ insulin. |

200 mg/kg in diabetic mice. |

|

14 |

Guar Gum |

Cyamopsis tetragonoloba |

Gallotannins |

Fermentation → SCFAs → ↑ GLP-1. |

7.6 g/meal in diabetics; 10% in C57BL mice. |

|

15 |

Hoodia Extract |

Hoodia gordonii |

Gordonosides F |

↑ GLP-1 & insulin (GPR119-dependent). |

200 mg/kg in mice (OGTT). |

|

16 |

Korean Pine |

Pinus koraiensis |

Free fatty acids (FFA) |

↑ GLP-1 postprandially. |

50 µM in human studies. |

|

17 |

Little Dragon (Tarragon) |

Artemisia dracunculus |

Tetralin |

↑ GLP-1 receptor binding affinity. |

500 mg/kg in KK-Aγ mice. |

|

18 |

Mango |

Mangifera indica |

Arginine |

DPP-4 inhibition → ↑ GLP-1. |

320 µg/mL (in vitro). |

|

19 |

Mate Tea |

Ilex paraguariensis |

3,5-O-Dicaffeoyl-D-quinic acid |

Acute ↑ GLP-1 secretion. |

50–100 mg/kg in mice. |

|

20 |

Myricetin |

Myrica rubra |

Myricetin |

Glucose-dependent insulin secretion (like GLP-1). |

250 µg/kg in Wistar rats. |

|

21 |

Olive Oil |

Olea europaea |

Oleic acid |

Modulates GLP-1 homeostasis. |

Human dietary studies. |

|

22 |

Phlomoides rotata |

Shanzhiside methylester |

GLP-1 receptor agonist. |

10–300 µg in Wistar rats. |

|

|

23 |

Plantago indica |

Iridoid glycosides |

Fiber → SCFAs → ↑ GLP-1. |

23 g fiber in humans. |

|

|

24 |

Panax Ginseng |

Panax ginseng |

Ginsenosides (Rb1, Re) |

Sweet taste receptors → ↑ GLP-1. |

10–20 mg/kg in mice. |

|

25 |

Pomelo |

Citrus maxima |

Naringenin |

↓ Circulating GLP-1 (receptor modulation). |

300–1200 mg/kg in Zucker rats. |

|

26 |

Pygeum |

Prunus africana |

Myristic acid |

↓ DPP-4 → prolongs GLP-1 half-life. |

100–400 mg/kg in Wistar rats. |

|

27 |

Quercetin |

Quercus spp. |

Quercetin |

Anti-diabetic via GLP-1 receptor. |

10–40 mg/kg in rats/humans. |

|

28 |

Quinine |

Cinchona calisaya |

Quinine |

Bitter taste receptors → ↑ GLP-1 (no nausea). |

NCI-H716 cell line. |

|

29 |

Scabra |

Gentiana scabra |

Gentiopicrin |

G-protein-mediated ↑ GLP-1 secretion. |

100 mg/kg in db/db mice. |

|

30 |

Sour Orange |

Citrus aurantium |

Hexane fraction (HFCA) |

↑ GLP-1 secretion in L-cells. |

NCI-H716 cell studies. |

|

31 |

Soybean |

Glycine max |

Glyceollins |

↑ GLP-1 → insulinotropic effects. |

20 mg/kg in diabetic mice. |

|

32 |

Sweet Potato |

Ipomoea batatas |

Quinic acid derivatives |

↑ GLP-1, ↓ glycemia. |

10 mg/mL in GLUTag cells. |

|

33 |

Vitis vinifera (Grape) |

Vitis vinifera |

Anthocyanins |

↑ Plasma GLP-1. |

500 mg/kg in Wistar rats. |

|

34 |

Wheat |

Triticum aestivum |

Fiber (SCFAs) |

Fermentation → ↑ GLP-1. |

24 g/day in humans. |

5. Comparison of Natural GLP-1 Agoinst with Existing GLP-1 Agonist

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to nutrient intake. While endogenous GLP-1 has a short half-life (<2 min) due to rapid degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), synthetic GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are engineered for prolonged action, making them effective for obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) management [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. As shown in Table 2.

Comparison of Natural & Synthetic GLP-1 agonist

|

Features |

Natural GLP-1 |

Synthetic GLP-1 Ras |

|---|---|---|

|

Source |

Endogenous (intestinal L-cells) |

Engineered (exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide) |

|

Half-life |

1–2 min (rapid DPP-4 degradation) |

Hours to days (DPP-4 resistant) |

|

Administration |

Not feasible (requires continuous IV infusion) |

Subcutaneous/oral (e.g., Rybelsus®) |

|

Mechanism |

Glucose-dependent insulin secretion, short-term satiety |

Enhanced CNS-mediated appetite suppression |

|

Weight Loss Efficacy |

Minimal (~1–2 kg) |

Significant (5–22.5% of body weight) |

|

HbA1c Reduction |

Mild (postprandial effect only) |

1–2% sustained reduction |

|

Cardiovascular Benefits |

Limited |

Proven (↓ MACE, e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide) |

|

Side Effects |

None (physiological levels) |

Nausea, vomiting, pancreatitis risk (rare) |

|

Clinical Use |

Research only (no therapeutic application) |

Approved for T2D, obesity, CVD risk reduction |

|

Cost/Accessibility |

NA |

High Cost |

6. Conclusions

The exploration of plant-derived GLP-1 receptor agonists underscores the vast potential of natural products in managing T2DM and obesity. Key findings include:

(1) Diverse Mechanisms: Plants like cinnamon (cinnamaldehyde), bitter melon (karavilagenine E), and ginseng (ginsenosides) modulate GLP-1 via DPP-4 inhibition, receptor activation, and SCFA production, offering multi-targeted effects beyond glucose control.

(2) Advantages Over Synthetics: Natural agonists often exhibit fewer gastrointestinal side effects and additional benefits (e.g., anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering), though their efficacy and half-life are inferior to drugs like semaglutide.

(3) Clinical Gaps: While preclinical data (e.g., berberine’s 500 mg/kg dose in rats) are promising, human trials are sparse, with only cinnamon, coffee, and wheat fiber tested in modest cohorts.

(4) Future Directions:

○ Bioavailability enhancement (e.g., nanoformulations of quercetin).

○ Synergistic combinations (e.g., berberine + metformin).

○ Long-term safety studies to address variability in plant extracts.

Author Contributions

A.V.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation; S.M.: investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; S.D.: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis; S.S.K.: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing—reviewing and editing; G.N.D.: supervision, resources, critical review, validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

During the preparation of this work, the author’s used Grammarly& QuillBot to assist with language refinement, grammar checking, and improvement of academic readability. After using this tool, the authors critically reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the accuracy, originality, and integrity of the published article.

References

- 1.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- 2.

Bergenstal, R.M.; Layne, J.E.; Zisser, H.; et al. Accuracy of a fourth-generation continuous glucose monitoring system in patients with diabetes: A pivotal trial. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 456–463.

- 3.

Brown, S.A.; Kovatchev, B.P.; Raghinaru, D.; et al. Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1125–1136.

- 4.

Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2022, 399, 2243–2256.

- 5.

Shapiro, A.M.J.; Pokrywczynska, M.; Ricordi, C. Clinical pancreatic islet transplantation. Cell. Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101044.

- 6.

DeFronzo, R.A. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2009, 58, 773–795.

- 7.

Patel, P.; Macerollo, A. Diabetes mellitus: Diagnosis and screening. J. R. Soc. Med. 2010, 103, 433–443.

- 8.

Mohan-Harsh. Textbook of Pathology, 7th ed.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2015.

- 9.

Fu, Z.; Gilbert, E.R.; Liu, D. Regulation of insulin synthesis and secretion and pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2013, 9, 25–53.

- 10.

Halban, P.A. Proinsulin processing in the regulated and the constitutive secretory pathway. Diabetologia 1994, 37, S65–S72.

- 11.

Halban, P.A.; Polonsky, K.S.; Bowden, D.W.; et al. Beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1751–1758.

- 12.

Christensen, A.A.; Gannon, M. The Beta Cell in type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2019, 19, 81.

- 13.

Danisnger, M. Early Signs and Symptoms of Diabetes. 2021. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/diabetes/understanding-diabetes-symptoms (accessed on 5 April 2025)

- 14.

Okur, M.E.; Karantas, I.D.; Siafaka, P. Diabetes Mellitus: A review on Pathophysiology, Current status of oral medeications and future perspectives. Acta Pharm. Sci. 2017, 55, 61–82.

- 15.

Tripathi, K.D. Essentials Medical Pharmacology, 8th ed.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- 16.

Manandhar, B.; Ahn, J.M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogs: Recent Advances, new possibilities and therapeutic implications. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 1020–1037.

- 17.

Kruszynska, Y.T.; Olefsky, J.M. Cellular and mechanisms of non- insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Investig. Med. Off. Publ. Am. Fed. Clin. Res. 1996, 44, 413–428.

- 18.

Naslund, E.; Barkeling, B.; King, N.; et al. Energy intake and appetite are suppressed by glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) in obese men. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1999, 23, 304–311.

- 19.

Michael, A.; Danlel, R.; Wefers, J.; et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes—State of the art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102.

- 20.

Singh, R.; Ahmad Bhat, G.; Sharma, P. GLP-1 secretagogues potential of medicinal plants in management of diabetes. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2015, 4, 197–202.

- 21.

Barrea, L.; Annunziata, G.; Muscogiuri, G.; et al. Could hop- derived bitter compounds improve glucose homeostasis by stimulating the secretion of GLP-1. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 528–535.

- 22.

Rios, J.L.; Andujar, I.; Schinella, G.R.; et al. Modulation of diabetes by natural products and medicinal plants via incertins. Planta Medica 2019, 85, 825–839.

- 23.

Kim, K.S.; Jang, H.J. Medicinal plants Qua Glucagon-Like peptide-1 Secretagogue via Intestinal Nutrient Sensors. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 171742.

- 24.

Shin, M.H.; Choi, E.K.; Kim, K.S.; et al. Hexane Fractions of Bupleurum falcatum L. Stimulates Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Secretion through G-Mediated pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 13, 982165.

- 25.

Medagama, A.B. The glycemic outcomes of cinnamon, a review of the experimental evidence and clinical trials. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 108.

- 26.

Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y. The emerging possibility of the use of geniposide in the treatment of cerebral diseases: A review. Chin. Med. 2021, 28, 16–86.

- 27.

Chang, C.L.T.; Lin, Y.; Bartolone, A.P.; et al. Herbal Therapies for Type 2 DiabetesMellitus: Chemistry, Biology and potential Applications of Selected Plants and compounds. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. Artic. 2013, 33, 378657.

- 28.

Hussein, G.M.E.; Matsuda, H.; Nakamura, S.; et al. Mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis) promotes satiety and body weight lowering in mice: Involvement of glucagon-like peptide-1. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1849–1855.

- 29.

Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yi, X.; et al. Myricetin: A potent approach for the treatment of type 2 diabetes as a natural class B GPCR agonist. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2603–2611.

- 30.

Shi, G.J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Q.H.; et al. In vitro and vivo evidence that quercetin protects against diabetes and its complications: A systemic review of the literature. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1085–1099.

- 31.

Choi, E.K.; Kim, K.S.; Jang, H.J. Hexane fraction of citrus aurantium L.stimulates glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion via membrane depolarization in NCI-H716 cells. Biochip J. 2012, 192, 41–47.

- 32.

Uccellatore, A.; Genovese, S.; Dicembrini, I.; et al. Composition Review of short acting and Low acting Glucagon- like peptide-1 Receptor agonists. Diabetes Ther. 2015, 6, 239–256.

- 33.

Minambres, L.; Filion, K.B.; Tsoukas, M.A.; et al. Review on various GLP-1 agonist. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 86, 103363.

- 34.

Gentilella, R.; Pechtner, V.; Corcos, A.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes treatment: Are they all the same? Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2019, 35, e3070.

- 35.

Dewi, N.K.; Ramona, Y.; Saraswati, M.R.; et al. The potential of the flavonoid content of Ipomoea batatas L. as an alternative analog GLP-1 for diabetes type 2 treatment—Systematic review. Metabolites 2023, 14, 29.

- 36.

Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 72–130.

- 37.

Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002.

- 38.

Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216.

- 39.

Lean, M.E.J.; Leslie, W.S.; Barnes, A.C.; et al. Durability of a primary care-led weight-management intervention for remission of type 2 diabetes: 2-year results of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 344–355.

- 40.

FDA. Wegovy (Semaglutide) Prescribing Information; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021.

- 41.

Andersson, U.; Berger, K.; Högberg, A.; et al. Effects of rose hip intake on risk markers of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: A randomized, double-blind, cross-over investigation in obese persons. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 585–590.

- 42.

Holst, J.J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 1409–1439.

- 43.

Drucker, D.J.; Nauck, M.A. The incretin system: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2006, 368, 1696–1705.

- 44.

Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: Physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 525–536.

- 45.

DeFronzo, R.A.; Ratner, R.E.; Han, J.; et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1092–1100.

- 46.

Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322.

- 47.

Knudsen, L.B.; Lau, J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 155.

- 48.

Davies, M.; Færch, L.; Jeppesen, O.K.; et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): A randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 971–984.

- 49.

Nauck, M.A. GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: Their pharmacology and associated clinical outcomes. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1–15.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.