Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, characterized by complex pathological processes including ionic imbalance, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Carvacrol, a naturally occurring monoterpenoid phenol, has gained attention in drug development for its potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7)-inhibitory properties. This review summarizes current evidence regarding the neuroprotective effects of carvacrol in various in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischemia and hypoxia. Mechanistic insights reveal that carvacrol modulates multiple molecular pathways, mitigates oxidative damage, suppresses neuroinflammation, alleviates neuronal apoptosis, and inhibits TRPM7 channel activity in cerebral ischemia and hypoxia. Finally, the broader applications of carvacrol in various diseases and its translational prospects are discussed, emphasizing the need for further preclinical and clinical studies to facilitate its development into a novel neuroprotective agent and adjunctive drug for stroke therapy.

- Open Access

- Review

Neuroprotective Effects of Carvacrol in Cerebral Ischemia and Hypoxia

- Xin-Yang Zhang 1,2,

- Hio-Lam Ho 1,2,

- Zhong-Ping Feng 2,*,

- Hong-Shuo Sun 1,2,3,4,*

Author Information

Received: 30 Jun 2025 | Revised: 18 Aug 2025 | Accepted: 19 Aug 2025 | Published: 06 Feb 2026

Abstract

Keywords

carvacrol | neuroprotection | cerebral ischemia | hypoxia | oxidative stress | neuroinflammation | apoptosis | TRPM7 channel | stroke therapy | natural compounds

1. Introduction

Stroke continues to be one of the leading causes of global mortality and long-term disability. Ischemic strokes, which comprise approximately 85% of all stroke cases, impose a substantial global burden by profoundly affecting patients, caregivers, and healthcare systems [1,2]. The increasing incidence of stroke is closely associated with aging populations and the growing prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity [1]. Ischemic brain injury initiates a cascade of pathological events, including excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation, ultimately leading to neuronal death [3]. In hypoxic-ischemic brain injury (HIBI), acute energy failure disrupts ion homeostasis, leading to calcium overload and subsequent neuronal death through excitotoxicity and oxidative stress [4,5]. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) results in sustained reductions in cerebral blood flow, promoting neurodegeneration and cognitive decline via oxidative stress, inflammation, and the accumulation of misfolded proteins [6,7]. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is currently the only FDA-approved pharmacological agent for acute ischemic stroke; however, its clinical application is constrained by a narrow therapeutic time window, a high risk of hemorrhagic transformation, and strict eligibility criteria [8,9]. This has driven ongoing efforts in stroke research to identify alternative therapeutic strategies and develop novel drugs.

Given the diverse and cascading pathological processes underlying ischemic and/or hypoxic brain damage, there is increasing interest in natural compounds with broad therapeutic targets [10,11]. Natural products, recognized for their ability to modulate various pathological pathways, coupled with a relatively favorable safety profile, are emerging as promising candidates for neuroprotection in complex disorders such as stroke [11].

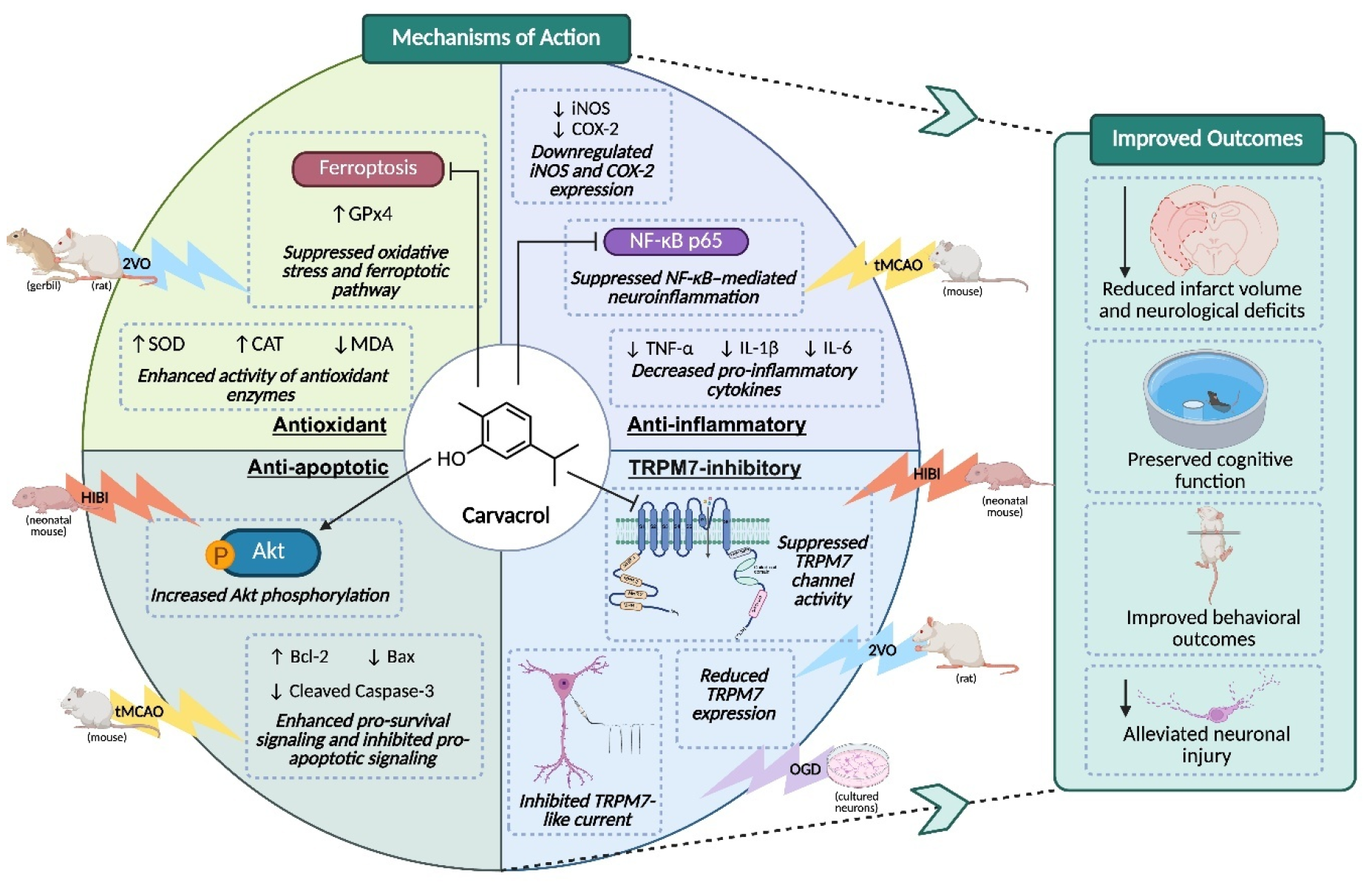

Carvacrol, a monoterpenoid phenol found in oregano oil, has drawn increasing interest for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects in models of ischemic stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy [12,13,14]. Our prior studies have demonstrated that carvacrol inhibits the activity of transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) ion channels, as evidenced by whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, and exerts neuroprotective effects in both in vivo and in vitro cerebral ischemic-hypoxic conditions [15]. These findings support further investigation into carvacrol as a promising natural therapeutic candidate. Accordingly, this review focuses on the neuroprotective potential and translational value of carvacrol in the context of cerebral ischemic and hypoxic damage (Figure 1).

2. Overview of Carvacrol

Carvacrol (chemical name 5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) is a naturally occurring monoterpenoid phenol predominantly found in the essential oils of oregano (Origanum vulgare) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris). It is also present in other aromatic plants such as pepperwort (Lepidium flavum) and wild bergamot (bergamia Loise var. Citrus aurantium), contributing to their distinctive aromas [12,13].

Chemically, it belongs to the class of terpenoids (specifically a monoterpene phenol) and is an isomer of thymol. Given its phenolic structure, carvacrol has long been recognized for its bioactive properties (e.g., as an antimicrobial and flavoring agent) and is widely used as a food additive [16]. It possesses a distinct structural configuration, featuring a hydroxyl group positioned ortho to a methyl group and para to an isopropyl group on a benzene ring [17], which imparts a relatively low molecular weight (~150 Da), lipophilicity, and the ability to interact with biological membranes. This structural configuration underlies its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities and supports its classification as a natural compound with medicinal potential [17,18].

2.1. Antioxidant Effects

Carvacrol has shown antioxidant properties across diverse experimental models. Its phenolic structure enables effective scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby mitigating oxidative stress. In studies involving restraint stress-induced oxidative damage, carvacrol administration reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and enhanced the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in the brain, liver, and kidney tissues [19]. Similarly, in models of acrylamide-induced hepatotoxicity, carvacrol supplementation decreased oxidative markers and strengthened antioxidant defences, indicating its protective role against chemically induced oxidative damage [20]. These findings underscore the capacity of carvacrol to modulate oxidative stress pathways, highlighting its potential in managing conditions characterized by oxidative imbalance.

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Beyond its antioxidant capacity, the anti-inflammatory effects of carvacrol are largely attributed to the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), through modulation of signaling pathways including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3). In a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced sepsis model, carvacrol treatment reduced systemic IL-6 levels and mitigated histopathological damage in liver, lungs, and heart [21]. In a myocardial dysfunction model, carvacrol alleviated cardiac injury by inhibiting the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)/NF-κB axis and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation in cardiomyocytes [22]. Similarly, in a rat model of gastric mucosal injury, carvacrol reduced mucosal inflammation by limiting pro-inflammatory cytokines release [23]. These findings highlight the ability of carvacrol to attenuate inflammation through multiple mechanisms, supporting its therapeutic potential in neurological inflammatory conditions.

2.3. Anti-Apoptotic Effects

Carvacrol also exhibits anti-apoptotic actions. In an LPS-induced myocardial injury model, carvacrol attenuated cardiomyocyte apoptosis by reversing the LPS-induced alterations in the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, resulting in decreased Bax and caspase-3 levels and increased Bcl-2 expression following carvacrol treatment [22]. Similarly, in models of mercuric chloride-induced testicular toxicity and diabetic rat testes, carvacrol administration reduced Bax and caspase-3 levels, elevated Bcl-2 expression, and attenuated germ cell apoptosis in parallel with improved oxidative stress markers, suggesting its protective effect against testicular cell apoptosis across different pathological contexts [24,25]. Consistent with these observations, in an ethanol-induced hippocampal injury model, carvacrol mitigated neuronal apoptosis by regulating caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2, and phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase (p-ERK), thereby preserving hippocampal neuronal integrity [26]. Furthermore, in cultured neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, carvacrol protected against Fe2+-induced apoptosis through suppression of mitogen-activated protein kinase/Jun N-terminal kinase (MAPK/JNK)-NF-κB signaling, further indicating direct modulation of apoptosis-related pathways in neural cells [27]. These findings underscore the ability of carvacrol to modulate apoptotic pathways, thereby contributing to its cytoprotective effects across various organ systems.

2.4. Inhibition against TRPM7

TRPM7, a divalent cation channel permeable to zinc, magnesium, calcium, and other trace metals, is broadly expressed across various cell types and tissues and has been implicated in numerous physiological and pathological processes [28,29,30,31,32]. Previous studies have confirmed that carvacrol, a natural non-selective inhibitor, effectively inhibits TRPM7 channel activity. In HEK293 cells overexpressing TRPM7, carvacrol inhibited TRPM7-mediated currents in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 of approximately 306 μM [33]. This inhibitory effect was also observed in cultured hippocampal CA3-CA1 neurons, suggesting physiological relevance in the central nervous system [33]. In a later study on HIBI, our lab illustrated that carvacrol inhibits TRPM7 currents in HEK293 cells overexpressing TRPM7 and hippocampal neurons, thereby reducing OGD-induced neuronal damage in vitro and, in vivo, attenuating infarct volume and enhancing functional recovery [15]. Furthermore, TRPM7 modulation by carvacrol has also been implicated in various non-neuronal cell types. In glioblastoma U87 cells, carvacrol reduced cell viability, migration, and invasion, effects attributed to suppression of TRPM7 channel and downstream signaling pathways [34]. In breast cancer cells, carvacrol inhibited TRPM7 currents and induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells, along with changes in cyclin protein expression, and these effects were abolished by TRPM7 knockdown, thereby supporting a TRPM7-mediated mechanism [35]. Collectively, these findings establish carvacrol as a natural inhibitor of TRPM7 channels in both neuronal and non-neuronal systems, providing a mechanistic basis for its biological activities observed across diverse experimental models. Comparatively, another natural, non-selective TRPM7 inhibitor, Xyloketal B, has also exhibited therapeutic effects, particularly in ischemic and hypoxic brain damage [36,37,38,39].

3. Protective Effects of Carvacrol in Cerebral Ischemia and Hypoxia Models

Carvacrol has demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects in various in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischemia and hypoxia, including HIBI [15], focal cerebral ischemia [40], and CCH [41]. These protective effects are mediated by its ability to reduce oxidative stress, suppress neuroinflammation, inhibit neuronal cell death, and modulate TRPM7 channel activity, all of which are critical contributors to stroke progression [15,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

3.1. Antioxidant and Anti-Ferroptotic Effects in Cerebral Ischemia Models

Oxidative stress is a major driver of neuronal injury in ischemic stroke, leading to lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and cell death [47]. Targeting oxidative stress has been proposed as a promising therapeutic strategy for stroke management [47]. Moreover, oxidative stress is a key initiator of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation and glutathione depletion [48]. Carvacrol has demonstrated robust antioxidant and anti-ferroptotic effects in different models of cerebral ischemia and hypoxia. In a gerbil model involving transient bilateral carotid artery ligation followed by reperfusion, carvacrol treatment significantly improved performance in the Morris water maze test, indicating preserved cognitive function [42]. At the molecular level, carvacrol attenuated hippocampal neuronal death by decreasing the levels of lipid peroxidation markers and enhancing the expression of GPx4, a key enzyme in ferroptosis inhibition [42]. These results indicate that carvacrol may protect neurons by suppressing oxidative stress and ferroptotic pathways. Similarly, in a CCH rat model using permanent bilateral occlusion of the carotid arteries (2VO), carvacrol improved spatial learning and memory and preserved hippocampal morphology [44]. Biochemical assays further revealed that carvacrol reduced MDA levels while increasing the activity of SOD and CAT in the hippocampus [44]. These consistent findings across transient and chronic ischemic paradigms highlight the potent antioxidant capacity of carvacrol and its ability to mitigate both lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis.

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Carvacrol in Focal Ischemia and Reperfusion Models

Neuroinflammation plays a pivotal role in the progression of ischemic brain injury by exacerbating blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, promoting leukocyte infiltration, and amplifying secondary neuronal damage [49]. Targeting inflammation after stroke, therefore, represents a promising neuroprotective strategy [49]. Carvacrol also exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects in cerebral ischemia, primarily through broad-spectrum suppression of ischemia-induced inflammatory cascades. In a rodent transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) model, carvacrol administration exerted neuroprotective effects, as evidenced by alleviated infarct severity and neurological deficits [40]. Carvacrol treatment led to decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, as well as reductions in myeloperoxidase activity [43]. Carvacrol also downregulated the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), two enzymes central to post-ischemic inflammation [43]. These effects were accompanied by elevated SOD activity and lowered MDA concentrations in the ischemic cortex, indicating that the anti-inflammatory action was complemented by antioxidant benefits. Notably, treatment with carvacrol suppressed the tMCAO-induced elevation of NF-κB p65 expression [43], a central mediator of neuroinflammation [50]. Collectively, these findings indicate that carvacrol exerts neuroprotective effects through the suppression of neuroinflammation.

3.3. Neuroprotection through Akt-Mediated Anti-Apoptotic Signaling

Neuronal apoptosis is a major form of cell death following cerebral ischemia and hypoxia, triggered by pathological cascades including oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and ionic imbalance [51]. These interconnected mechanisms ultimately converge on intrinsic apoptotic pathways, leading to progressive neuronal loss and functional impairment after stroke [51,52]. Carvacrol has demonstrated anti-apoptotic efficacy in both in vivo and in vitro models of ischemic and hypoxic brain injury. In rodent models of tMCAO, systemic administration of carvacrol significantly reduced infarct volume and improved neurological function in a dose-dependent manner [40]. Post-treatment at 2 h after reperfusion remained effective, and intracerebroventricular administration extended the therapeutic window to at least 6 h [40]. Mechanistically, these effects were associated with a marked decrease in cleaved caspase-3 expression, a key marker of apoptosis, and an increase in phosphorylation of protein kinase B (Akt) [40]. Notably, pharmacological blockade of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway abolished the neuroprotection conferred by carvacrol, implicating Akt signaling as a central component of its anti-apoptotic mechanism [40]. Similar findings have been reported in neonatal HIBI [15]. Carvacrol restored the balance between anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and pro-apoptotic Bax proteins, increased Akt phosphorylation, thereby preventing activation of downstream caspases and maintaining neuronal viability in neonatal stroke [15,53].

3.4. Neuroprotection through TRPM7 Channel Inhibition

In the stroke drug development, the glutamate receptor antagonists did not achieve the expected neuroprotection in stroke clinical trials [3,54], research has increasingly focused on non-glutamatergic targets, such as transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Among the TRP channels, TRPM7 is highly permeable to calcium and zinc and plays a critical role in mediating ionic imbalance, oxidative stress, and apoptotic neuronal injury during cerebral ischemia and hypoxia [55,56,57]. Inhibition of TRPM7 channels has been identified as one of the potential mechanisms by which carvacrol exerts its neuroprotective effects in stroke.

Our lab has demonstrated that carvacrol inhibits TRPM7 channel activities and provides neuroprotection in the neonatal HIBI mouse model [15]. Specifically, carvacrol was found to inhibit TRPM7 currents in HEK293 cells transfected to overexpress TRPM7 and to suppress TRPM7-like currents in hippocampal neurons [15], underscoring its channel-blocking capabilities. This inhibition effectively alleviated neuronal damage induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) [15]. Moreover, carvacrol pre-treatment reduced brain infarct volume in vivo, improved neurobehavioral recovery, enhanced pro-survival signaling pathways, and downregulated pro-apoptotic markers [15]. These results highlight the potential of carvacrol as a promising natural therapeutic agent for neuroprotection through the modulation of TRPM7 activity. In an adult rat model of CCH induced by 2VO combined with femoral artery blood withdrawal, carvacrol treatment attenuated hippocampal neuronal degeneration, reduced TRPM7 expression in the hippocampus, and suppressed microglial activation and oxidative stress [41]. These protective effects were further associated with decreased intracellular zinc accumulation in neurons within the hippocampal pyramidal layer, suggesting that inhibition of TRPM7-mediated zinc influx contributes to the neuroprotective actions of carvacrol [41]. These findings demonstrate that TRPM7 inhibition is a conserved mechanism of the neuroprotective effect of carvacrol across developmental stages and ischemia models.

Comparatively, Xyloketal B, another naturally derived, non-selective TRPM7 blocker with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, has shown neuroprotective effects across various stroke models [39]. Originally isolated from the marine fungus Xylaria sp., Xyloketal B has demonstrated efficacy in both adult and neonatal models of cerebral ischemia and hypoxia [39]. In mice subjected to tMCAO, Xyloketal B reduced infarct volume, improved neurological function, and preserved BBB integrity by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators such as TLR4, NF-κB, and pro-inflammatory cytokines [36]. In neonatal hypoxic-ischemic models, it attenuated neuronal apoptosis and calcium overload, while promoting functional recovery [37]. In vitro studies further support its antioxidant and mitochondrial-protective actions under OGD conditions [38]. These findings, together with evidence for carvacrol, highlight the therapeutic potential of naturally sourced TRPM7 inhibitors in mitigating ischemic and hypoxic brain injury.

3.5. Broader Neurovascular Protection in Experimental Stroke Models

Beyond ischemic models, carvacrol has also shown efficacy in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). ICH represents an estimated 10–20% of stroke incidences worldwide [58]. In a collagenase-induced mouse model of ICH, carvacrol treatment improved neurological function and significantly reduced cerebral edema, as evidenced by decreased brain water content and reduced Evans Blue extravasation [46]. These effects were associated with dose-dependent suppression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) mRNA and protein expression in peri-lesional regions, suggesting that carvacrol may modulate water channel activity and BBB integrity to mitigate edema formation [46]. The shared involvement of BBB breakdown in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke underscores the promise of carvacrol as a versatile therapeutic agent applicable to various stroke subtypes [59].

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Carvacrol represents a promising natural compound with multi-target neuroprotective actions relevant to stroke [15,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Its ability to modulate diverse pathological pathways highlights its therapeutic potential as a novel pharmacological treatment and a naturally derived adjunctive therapy [11]. Despite these encouraging findings, carvacrol has not undergone systematic clinical evaluation, and several gaps remain to be addressed. First, further preclinical studies are needed to optimize dosage, define the therapeutic time window, and assess long-term safety and efficacy, especially in chronic stroke models and aged animals. Second, although carvacrol shows therapeutic efficacy in experimental models, important pharmacokinetic properties such as oral bioavailability, metabolic stability, and BBB permeability still require detailed investigation. Innovative delivery strategies, such as nanoformulations or complexation with β-cyclodextrin, may help improve its solubility and central nervous system bioavailability, thereby enhancing its translational potential [60,61].

Moreover, additional pharmacodynamic studies should explore whether carvacrol interacts with other TRP channels or redox-sensitive proteins beyond TRPM7, specifically in the context of cerebral ischemia and hypoxia [62,63], potentially broadening its therapeutic spectrum or more clearly defining its molecular targets. Evaluating carvacrol in combination with current standard treatments (e.g., thrombolytic therapy [8,9,10]) or neuroprotective interventions (e.g., hypothermia, dietary factors, or exercise [64]) could also reveal synergistic benefits.

Beyond its neuroprotective effects in stroke models, carvacrol has demonstrated therapeutic potential across a range of neurological and non-neurological conditions. Carvacrol exerted antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effects, thereby providing neuroprotection against amyloid-beta (Aβ)-induced toxicity and ameliorating cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease models [65,66,67,68]. In Parkinson’s disease models, carvacrol reduced the production of ROS and proinflammatory cytokines, and downregulated the upregulated expression of caspase-3, which prevented the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and improved motor functions [69,70,71]. In glioblastoma, carvacrol was shown to suppress tumor growth and invasion through TRPM7 inhibition, highlighting its role in modulating cell proliferation and migration in malignancies [34,72]. In experimental epilepsy models, post-status epilepticus treatment with carvacrol effectively prevented recurrent seizures, neuronal loss, and cognitive deficits, suggesting durable anti-epileptogenic and neuroprotective properties [73]. In addition, carvacrol ameliorated zinc-induced neurotoxicity and neuronal death following traumatic brain injury by downregulating TRPM7 expression [74], and conferred spinal cord protection by preserving blood-spinal cord barrier integrity in a contusion model [75]. These findings collectively support the broader applicability of carvacrol in therapeutic research and drug exploration aimed at TRPM7-associated pathologies.

In summary, carvacrol emerges as a versatile candidate for neuroprotective drug development. Moving forward, a systematic and multidisciplinary approach encompassing pharmacology, delivery science, and translational neuroscience is essential to fully realize its therapeutic potential in stroke management.

Author Contributions

X.-Y.Z.: writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing; H.-L.H.: writing—reviewing and editing; Z.-P.F.; conceptualization, supervision, resources, project administration, critical review; H.-S.S.: conceptualization, supervision, resources, project administration, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grants to HSS (RGPIN-2022-04589), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to ZPF (PJT-191824), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC) to HSS (G-23-0035032), and Heart & Stroke/Richard Lewar Centre of Excellence in Cardiovascular Research (HSRLCE) Studentship Award to XZ.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Feigin, V.L.; Stark, B.A.; Johnson, C.O.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820.

- 2.

Johnson, W.; Onuma, O.; Owolabi, M.; et al. Stroke: A global response is needed. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 634–634a.

- 3.

Dirnagl, U.; Iadecola, C.; Moskowitz, M.A. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: An integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999 22, 391–397.

- 4.

Douglas-Escobar, M.; Weiss, M.D. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: A review for the clinician. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 397–403.

- 5.

Sekhon, M.S.; Ainslie, P.N.; Griesdale, D.E. Clinical pathophysiology of hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest: A “two-hit” model. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 90.

- 6.

Duncombe, J.; Kitamura, A.; Hase, Y.; et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion: A key mechanism leading to vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Closing the translational gap between rodent models and human vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 2451–2468.

- 7.

Park, J.H.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, S.W.; et al. The effect of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion on the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease: A positron emission tomography study in rats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14102.

- 8.

Del Zoppo, G.J.; Saver, J.L.; Jauch, E.C.; et al. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: A science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2009, 40, 2945–2948.

- 9.

Fugate, J.E.; Rabinstein, A.A. Absolute and Relative Contraindications to IV rt-PA for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurohospitalist 2015, 5, 110–121.

- 10.

Chen, H.S.; Qi, S.H.; Shen, J.G. One-Compound-Multi-Target: Combination Prospect of Natural Compounds with Thrombolytic Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 134–156.

- 11.

Xie, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, D.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect for Cerebral Ischemia by Natural Products: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 607412.

- 12.

Imran, M.; Aslam, M.; Alsagaby, S.A.; et al. Therapeutic application of carvacrol: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3544–3561.

- 13.

Baser, K.H. Biological and pharmacological activities of carvacrol and carvacrol bearing essential oils. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3106–3119.

- 14.

Tareen, F.K.; Catenacci, L.; Perteghella, S.; et al. Carvacrol Essential Oil as a Neuroprotective Agent: A Review of the Study Designs and Recent Advances. Molecules 2024, 30, 104.

- 15.

Chen, W.; Xu, B.; Xiao, A.; et al. TRPM7 inhibitor carvacrol protects brain from neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. Mol. Brain 2015, 8, 11.

- 16.

Maczka, W.; Twardawska, M.; Grabarczyk, M.; et al. Carvacrol-A Natural Phenolic Compound with Antimicrobial Properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 824.

- 17.

Mondal, A.; Bose, S.; Mazumder, K.; et al. Carvacrol (Origanum vulgare): Therapeutic Properties and Molecular Mechanisms. In Bioactive Natural Products for Pharmaceutical Applications; Pal, D., Nayak, A.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 437–462.

- 18.

Mohammedi, Z. Carvacrol: An update of biological activities and mechanism of action. J. Chem. 2017, 1, 53–62.

- 19.

Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samini, F.; et al. Protective Effects of Carvacrol against Oxidative Stress Induced by Chronic Stress in Rat’s Brain, Liver, and Kidney. Biochem. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2645237.

- 20.

Cerrah, S.; Ozcicek, F.; Gundogdu, B.; et al. Carvacrol prevents acrylamide-induced oxidative and inflammatory liver damage and dysfunction in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1161448.

- 21.

Yan, C.; Kuang, W.; Jin, L.; et al. Carvacrol protects mice against LPS-induced sepsis and attenuates inflammatory response in macrophages by modulating the ERK1/2 pathway. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12809.

- 22.

Xu, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.T.; et al. Carvacrol alleviates LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB and NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes. J. Inflamm. 2024, 21, 47.

- 23.

Gunes-Bayir, A.; Guler, E.M.; Bilgin, M.G.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of Carvacrol on N-Methyl-N′-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) Induced Gastric Carcinogenesis in Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2848.

- 24.

Simsek, H.; Gur, C.; Kucukler, S.; et al. Carvacrol Reduces Mercuric Chloride-Induced Testicular Toxicity by Regulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Histopathological Changes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 4605–4617.

- 25.

Shoorei, H.; Khaki, A.; Khaki, A.A.; et al. The ameliorative effect of carvacrol on oxidative stress and germ cell apoptosis in testicular tissue of adult diabetic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 568–578.

- 26.

Wang, P.; Luo, Q.; Qiao, H.; et al. The Neuroprotective Effects of Carvacrol on Ethanol-Induced Hippocampal Neurons Impairment via the Antioxidative and Antiapoptotic Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 4079425.

- 27.

Cui, Z.W.; Xie, Z.X.; Wang, B.F.; et al. Carvacrol protects neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against Fe(2+)-induced apoptosis by suppressing activation of MAPK/JNK-NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 1426–1436.

- 28.

Runnels, L.W.; Yue, L.; Clapham, D.E. TRP-PLIK, a bifunctional protein with kinase and ion channel activities. Science 2001, 291, 1043–1047.

- 29.

Nadler, M.J.; Hermosura, M.C.; Inabe, K.; et al. LTRPC7 is a Mg· ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature 2001, 411, 590–595.

- 30.

Fleig, A.; Chubanov, V. Trpm7. In Mammalian Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Cation Channels; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume I, pp. 521–546.

- 31.

Chubanov, V.; Gudermann, T. Mapping TRPM7 function by NS8593. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7017.

- 32.

Bates-Withers, C.; Sah, R.; Clapham, D.E. TRPM7, the Mg 2+ inhibited channel and kinase. In Transient Receptor Potential Channels; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 173–183.

- 33.

Parnas, M.; Peters, M.; Dadon, D.; et al. Carvacrol is a novel inhibitor of Drosophila TRPL and mammalian TRPM7 channels. Cell Calcium 2009, 45, 300–309.

- 34.

Chen, W.L.; Barszczyk, A.; Turlova, E.; et al. Inhibition of TRPM7 by carvacrol suppresses glioblastoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 16321–16340.

- 35.

Li, L.; He, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. Carvacrol affects breast cancer cells through TRPM7 mediated cell cycle regulation. Life Sci. 2021, 266, 118894.

- 36.

Pan, N.; Lu, L.Y.; Li, M.; et al. Xyloketal B alleviates cerebral infarction and neurologic deficits in a mouse stroke model by suppressing the ROS/TLR4/NF-kappaB inflammatory signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1236–1247.

- 37.

Xiao, A.J.; Chen, W.; Xu, B.; et al. Marine compound xyloketal B reduces neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Mar. Drugs 2014, 13, 29–47.

- 38.

Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Ling, C.; et al. Marine compound Xyloketal B protects PC12 cells against OGD-induced cell damage. Brain Res. 2009, 1302, 240–247.

- 39.

Gong, H.; Bandura, J.; Wang, G.L.; et al. Xyloketal B: A marine compound with medicinal potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 230, 107963.

- 40.

Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; et al. Carvacrol, a food-additive, provides neuroprotection on focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33584.

- 41.

Hong, D.K.; Choi, B.Y.; Kho, A.R.; et al. Carvacrol attenuates hippocampal neuronal death after global cerebral ischemia via inhibition of transient receptor potential melastatin 7. Cells 2018, 7, 231.

- 42.

Guan, X.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; et al. The neuroprotective effects of carvacrol on ischemia/reperfusion-induced hippocampal neuronal impairment by ferroptosis mitigation. Life Sci. 2019, 235, 116795.

- 43.

Li, Z.; Hua, C.; Pan, X.; et al. Carvacrol Exerts Neuroprotective Effects Via Suppression of the Inflammatory Response in Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Rats. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1566–1572.

- 44.

Shahrokhi Raeini, A.; Hafizibarjin, Z.; Rezvani, M.E.; et al. Carvacrol suppresses learning and memory dysfunction and hippocampal damages caused by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 581–589.

- 45.

Suo, L.; Kang, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Carvacrol alleviates ischemia reperfusion injury by regulating the PI3K-Akt pathway in rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104043.

- 46.

Zhong, Z.; Wang, B.; Dai, M.; et al. Carvacrol alleviates cerebral edema by modulating AQP4 expression after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 555, 24–29.

- 47.

Li, Z.; Bi, R.; Sun, S.; et al. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Acute Ischemic Stroke-Related Thrombosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 8418820.

- 48.

Liu, D.; Yang, S.; Yu, S. Interactions Between Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress in Ischemic Stroke. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1329.

- 49.

Iadecola, C.; Anrather, J. The immunology of stroke: From mechanisms to translation. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 796–808.

- 50.

Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; et al. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023.

- 51.

Broughton, B.R.; Reutens, D.C.; Sobey, C.G. Apoptotic mechanisms after cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2009, 40, e331–e339.

- 52.

Mao, R.; Zong, N.; Hu, Y.; et al. Neuronal Death Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategy in Ischemic Stroke. Neurosci. Bull. 2022, 38, 1229–1247.

- 53.

Youle, R.J.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: Opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 47–59.

- 54.

Legos, J.J.; Tuma, R.F.; Barone, F.C. Pharmacological interventions for stroke: Failures and future. Expert. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2002, 11, 603–614.

- 55.

Sun, H.S. Role of TRPM7 in cerebral ischaemia and hypoxia. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3077–3083.

- 56.

Sun, H.S.; Jackson, M.F.; Martin, L.J.; et al. Suppression of hippocampal TRPM7 protein prevents delayed neuronal death in brain ischemia. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1300–1307.

- 57.

Aarts, M.; Iihara, K.; Wei, W.L.; et al. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell 2003, 115, 863–877.

- 58.

Qureshi, A.I.; Mendelow, A.D.; Hanley, D.F. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet 2009, 373, 1632–1644.

- 59.

Sweeney, M.D.; Zhao, Z.; Montagne, A.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 21–78.

- 60.

Xavier, E.S.; de Souza, R.L.; Rodrigues, V.C.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of Carvacrol-Loaded Nanoemulsion in a Mouse Model of Schistosomiasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 917363.

- 61.

Tiefensee Ribeiro, C.; Gasparotto, J.; Petiz, L.L.; et al. Oral administration of carvacrol/β-cyclodextrin complex protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced dopaminergic denervation. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 126, 27–35.

- 62.

Akan, T.; Aydin, Y.; Korkmaz, O.T.; et al. The Effects of Carvacrol on Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels in an Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox. Res. 2023, 41, 660–669.

- 63.

Wang, R.; Tu, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Roles of TRP Channels in Neurological Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 7289194.

- 64.

Costa, H.A.; Dias, C.JM.; Martins, V.A.; et al. Effect of treatment with carvacrol and aerobic training on cardiovascular function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 891–901.

- 65.

Azizi, Z.; Salimi, M.; Amanzadeh, A.; et al. Carvacrol and Thymol Attenuate Cytotoxicity Induced by Amyloid β25-35 via Activating Protein Kinase C and Inhibiting Oxidative Stress in PC12 Cells. Iran. Biomed. J. 2020, 24, 243–250.

- 66.

Jukic, M.; Politeo, O.; Maksimovic, M.; et al. In vitro acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties of thymol, carvacrol and their derivatives thymoquinone and thymohydroquinone. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 259–261.

- 67.

Kurt, B.Z.; Gazioglu, I.; Dag, A.; et al. Synthesis, anticholinesterase activity and molecular modeling study of novel carbamate-substituted thymol/carvacrol derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 1352–1363.

- 68.

Medhat, D.; El-Mezayen, H.A.; El-Naggar, M.E.; et al. Evaluation of urinary 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine level in experimental Alzheimer’s disease: Impact of carvacrol nanoparticles. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 4517–4527.

- 69.

Shah, S.; Pushpa Tryphena, K.; Singh, G.; et al. Neuroprotective role of Carvacrol via Nrf2/HO-1/NLRP3 axis in Rotenone-induced PD mice model. Brain Res. 2024, 1836, 148954.

- 70.

Manouchehrabadi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Azizi, Z.; et al. Carvacrol Protects Against 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in In Vivo and In Vitro Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 37, 156–170.

- 71.

Dati, L.M.; Ulrich, H.; Real, C.C.; et al. Carvacrol promotes neuroprotection in the mouse hemiparkinsonian model. Neuroscience 2017, 356, 176–181.

- 72.

Alanazi, R.; Nakatogawa, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Inhibition of TRPM7 with carvacrol suppresses glioblastoma functions in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 1483–1491.

- 73.

Khalil, A.; Kovac, S.; Morris, G.; et al. Carvacrol after status epilepticus (SE) prevents recurrent SE, early seizures, cell death, and cognitive decline. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 263–273.

- 74.

Lee, M.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, S.; et al. Carvacrol Inhibits Expression of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 7 Channels and Alleviates Zinc Neurotoxicity Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13840.

- 75.

Park, C.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, H.Y.; et al. Suppression of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 7 by Carvacrol Protects against Injured Spinal Cord by Inhibiting Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier Disruption. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 735–749.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.