Aging is a multifactorial biological process that leads to the gradual decline of physiological functions, contributing to the onset of age-related diseases. Nitazoxanide (NTZ) is an FDA-approved antiparasitic drug with anti-senescence effects. However, its anti-aging effects and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. This study investigated the anti-aging effects of NTZ in Caenorhabditis elegans and in a D-galactose (D-Gal)-induced accelerated aging mouse model. In C. elegans, NTZ treatment significantly extended both lifespan and healthspan, as demonstrated by reduced lipofuscin accumulation, decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and improved locomotor activity. In the D-Gal mouse model, NTZ treatment ameliorated cognitive and physical decline, improved skin tissue integrity, and protected hippocampal neurons from degeneration. Computational target prediction and pathway analysis identified 122 potential anti-aging targets of NTZ. Network pharmacology analysis revealed that NTZ targets the PI3K signaling pathway, a key regulator of aging, and identifies PI3K p110 catalytic isoform as a central hub in this cascade, confirming its pivotal role in NTZ-mediated anti-aging effects. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations further validated the stable binding of NTZ to PI3K p110 catalytic isoforms, demonstrating a high-affinity interaction that disrupts PI3K signaling. Together, these findings provide molecular evidence supporting NTZ as a promising candidate for anti-aging therapy, with potential applications in age-related diseases.

- Open Access

- Article

Anti-Aging Effects of Nitazoxanide in Caenorhabditis elegans and D-Galactose-Induced Accelerated Aging Mice

- Xianzhe Wang 1,

- Huilin Liu 1,

- Xiangchuan Wang 2,

- Hongjie Zhang 2,

- Xiuping Chen 1,*

Author Information

Received: 17 Jun 2025 | Revised: 03 Sep 2025 | Accepted: 05 Sep 2025 | Published: 11 Feb 2026

Abstract

Keywords

Nitazoxanide | anti-aging | C. elegans | D-galactose | PI3Ks

1. Introduction

Aging is a complex, multifactorial biological process characterized by the progressive decline of physiological integrity, encompassing oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and extracellular matrix remodeling, which collectively drive susceptibility to age-related conditions such as muscle atrophy, cognitive decline, neurodegenerative diseases, and fibrosis [1,2,3]. This progressive deterioration at the cellular and tissue levels not only drives the onset of chronic conditions but also profoundly impacts both lifespan and healthspan [4]. Molecular mechanisms underlying aging, such as disabled macroautophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence, have become focal points for therapeutic intervention, as they converge on conserved signaling pathways like PI3K, mTOR, or AMPK that govern metabolic homeostasis and longevity [5].

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) and the D-galactose (D-gal)-induced accelerated aging mouse model are pivotal tools in anti-aging research, owing to their well-characterized aging phenotypes and conserved molecular pathways with humans [6]. C. elegans offers genetic tractability and a short lifespan, with aging marked by reduced motility, lipofuscin accumulation, and oxidative stress [7]. While D-gal-treated mice exhibit hallmarks of mammalian aging, including collagen loss, cognitive impairment, and muscle wasting, driven by oxidative stress and metabolic dysregulation [8]. These models recapitulating key features of human aging make it possible to investigate anti-aging drug candidates.

Nitazoxanide (NTZ), an FDA-approved antiparasitic drug, has emerged as a promising candidate for therapeutic repurposing due to its broad range of activities, including antitumor, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects [9,10]. Recent studies in C. elegans have shown that NTZ and its active metabolite, tizoxanide, can extend lifespan and improve healthspan by activating AMPK-dependent pathways [11]. Our previous research in pulmonary fibrosis models further demonstrated that NTZ inhibits cellular senescence and mitigates fibrotic remodeling by targeting the PI3K signaling pathway, an upstream regulator of AMPK [12]. While these findings highlight NTZ’s potential to modulate conserved aging pathways, its systemic anti-aging effects in mammals and the mechanistic interplay between PI3K signaling and organismal aging remain uncharacterized. Given NTZ’s established clinical safety profile and its ability to inhibit cellular senescence, it presents a compelling candidate for investigating whether its senescence-inhibitory mechanisms in fibrosis can extend to broader anti-aging effects in aging models.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to characterize NTZ’s anti-aging efficacy in the C. elegans aging model and D-gal-induced accelerated aging model. Our results demonstrate that NTZ significantly extends both lifespan and healthspan in C. elegans, reducing lipofuscin deposition and enhancing stress resistance, while mitigating D-gal-induced declines in mouse cognitive and physical function. Mechanistically, these effects correlate with the PI3K signaling pathway, positioning NTZ as a viable candidate for the development of anti-aging therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

Nitazoxanide (NTZ) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology (Shanghai, China) and D-galactose was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China).

2.2. C. elegans Culture

The wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans strain N2 and Escherichia coli OP50 strain were procured from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC, Minneapolis, MN, USA). C. elegans were maintained at 20 ℃ on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with live E. coli OP50. L4-stage worms were synchronized and prepared for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Lifespan Analysis

For lifespan analysis [13], the synchronized L4-stage nematodes were transferred to experimental plates, which were defined as a start time point (Day 0). The nematodes were cultivated on NGM plates supplemented with 30 mg/L floxuridine (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and seeded with 100 μL of E. coli OP50 culture containing either 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) or an equal volume of NTZ (dissolved in DMSO). Worms were transferred to new plates and counted every two days. Each treatment group consisted of three replicates, with 35 worms per replicate plate.

2.4. Locomotion Assay

For the assessment of the worm’s locomotion ability, individual worms at day 10 of L4-stage were allowed to freely move for 2 min to acclimate, and then their crawling trajectory was recorded for 30 s using the microscope.

2.5. Reactive OXYGEN Species (ROS) and Autofluorescence Detection

For ROS evaluation, individual worms at day 10 of L4-stage were incubated with 100 μM DCFH2-DA (Beyotime, China) for 30 min at 20 °C followed by washing with M9 buffer. For autofluorescence monitoring, the worms were immobilized in sodium azide on the agar pad. A wavelength of 488 nm was selected for ROS evaluation, and ex/em 546/600 nm was used for autofluorescence monitoring using the fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Worms were traced using ImageJ analysis to obtain fluorescence intensity and track crawling trajectory measurements.

2.6. D-Galactose-Induced Accelerated Aging Model

Eight-weeks BALB/c mice (Female, 21 ± 1.5 g) were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 6): Ctrl group, D-gal model group, 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg NTZ-treated groups. The Ctrl group received daily subcutaneous injections of 200 μL sterile saline, while the D-gal model and NTZ-treated groups were subcutaneously injected with 250 mg/kg D-gal dissolved in 200 μL saline daily to induce accelerated aging [14].

Starting from day 14 of D-gal administration, mice in the NTZ-treated groups received daily oral gavage of NTZ dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium (CMC-Na), while the Ctrl and D-gal model groups received an equal volume of vehicle (0.5% CMC-Na). All the animal procedures conducted were under the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee at the University of Macau.

2.7. Open Field Test

Open field test and rota-rod test were conducted after 11 weeks of treatment, and mice were sacrificed after 12 weeks of treatment. Samples of serum and tissue were collected for subsequent experiments. The open field test was conducted after 11 weeks of treatment using a transparent plastic box (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm). Each mouse was placed in the center of the box and allowed to freely explore for 3 min. The trajectory was recorded for 2 min using a video-tracking system.

2.8. Rota-Rod Test

The rota-rod test was performed after 11 weeks of treatment using a rota-rod apparatus (Xinruan Instruments, Shanghai, China). Mice were trained for 3 days before testing, with the rod accelerating from 4 to 40 rpm over 300 s. The maximum latency to fall was recorded as the average of three trials per mouse

2.9. Serum Antioxidant Analysis

Following 12 weeks of treatment, mice were euthanized, and blood samples were collected. The serum was separated by centrifugation. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the levels of methane dicarboxylic aldehyde (MDA) in the mice serum were measured using commercially available kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.10. Histological Staining

Tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 8 μm sections. Masson’s trichrome staining (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was performed to evaluate collagen deposition in the skin, while Nissl staining was used to assess neuronal integrity in the brain following the manufacturer’s instructions (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Staining was visualized under a microscope and quantified using Image J software.

2.11. Computational Target Fishing of NTZ

Potential NTZ targets were predicted using SwissTargetPrediction [15] and Pharmmapper database [16]. The targets identified from both databases were consolidated, and duplicates were removed. Targets related to senescence were screened in the Genecards database (https://www.genecards.org/, accessed on 31 May 2025) using “senescence” as the keyword, while aging-related genes were retrieved from the Human Aging database (https://genomics.senescence.info/, accessed on 31 May 2025) with “aging” as the search term. The Venny 2.1 tool was employed to identify the intersection between these three sets of targets, thereby identifying the specific targets through which NTZ may regulate aging by modulating senescence. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted on the intersecting targets using the OmicShare tools database [17] to explore the biological functions and pathways associated with NTZ’s potential anti-aging effects.

2.12. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Construction

Intersection targets were uploaded to the STRING database (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 31 May 2025) with a confidence score > 0.7 to generate PPI networks. Networks were visualized and analyzed in Cytoscape 3.9.1, and hub genes were identified using the CytoHubba plugin with the Degree of Network Centrality (DNMC) algorithm.

2.13. Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulation

The crystal structure of PI3K (PDB ID: 5VLR) was downloaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank. PrankWeb was employed to predict the ligand-binding pocket and perform molecular docking [18]. Docking poses were visualized using LigPlot+ v.2.2, and hydrogen bonds/interactions were annotated.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the iMOD server [19] and CABS-flex 2.0 [20] to assess the stability and conformational flexibility of the NTZ-PI3Kδ complex. Default parameters were used for both servers, with the docked PDB structure from the molecular docking serving as the input.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software 8.0, USA). All data represent at least 3 independent experiments or samples and are expressed as mean ± S.D. Multiple group statistics were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple group comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

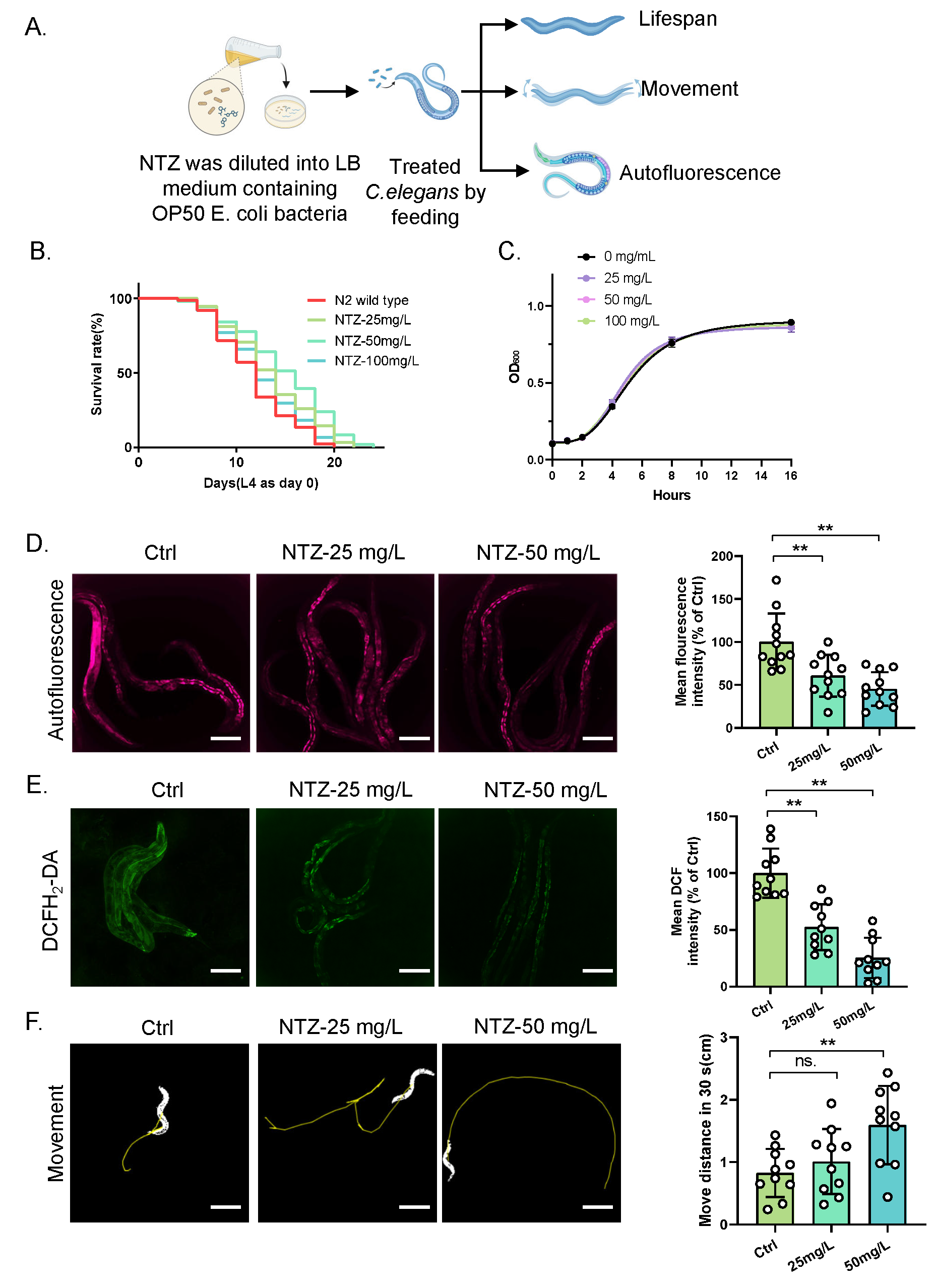

3.1. NTZ Extended Mean Lifespan and Health Span in C. elegans

Mean lifespan extension is a key indicator in anti-senescence research [21]. To investigate the anti-aging effects of NTZ, we first assessed its impact on lifespan in C. elegans (Figure 1A). Compared to the control group (with a mean lifespan of 11.82 days), nematodes treated with NTZ at concentrations of 25 mg/L, 50 mg/L, and 100 mg/L exhibited mean lifespan extensions of 8.5% (corresponding to an additional 1.00 days), 13.4% (1.58 days), and 7.3% (0.86 days), respectively (Figure 1B).

Given that improving healthy lifespan is a primary goal of anti-aging research, we further evaluated the effect of NTZ on the healthy lifespan of C. elegans by measuring accumulated lipofuscin autofluorescence. The control group exhibited significant accumulation of autofluorescent substances. In contrast, the group treated with 50 mg/L NTZ (the most effective concentration in lifespan assays) showed notably weaker autofluorescence intensity, which was 45.36 ± 19.47% (p < 0.01) of that in the control group (Figure 1C).

Additionally, the control group demonstrated elevated ROS levels, consistent with the reduced antioxidant capacity associated with aging. In comparison, worms treated with 50 mg/L NTZ exhibited significantly lower ROS levels, which was 25.5 ± 17.87% (p < 0.01) of that in the control group (Figure 1D).

Furthermore, at the physiological level, nematodes treated with 50 mg/L NTZ exhibited enhanced locomotor activity compared to the control group, with a significant increase in movement distance from 0.83 ± 0.38 cm to 1.59 ± 0.63 cm over 30 s (p < 0.01) along with more regular movement trajectories (Figure 1E).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that NTZ not only extends the mean lifespan of C. elegans but also delays age-related decline in physiological function, supporting its potential role in enhancing healthy lifespan.

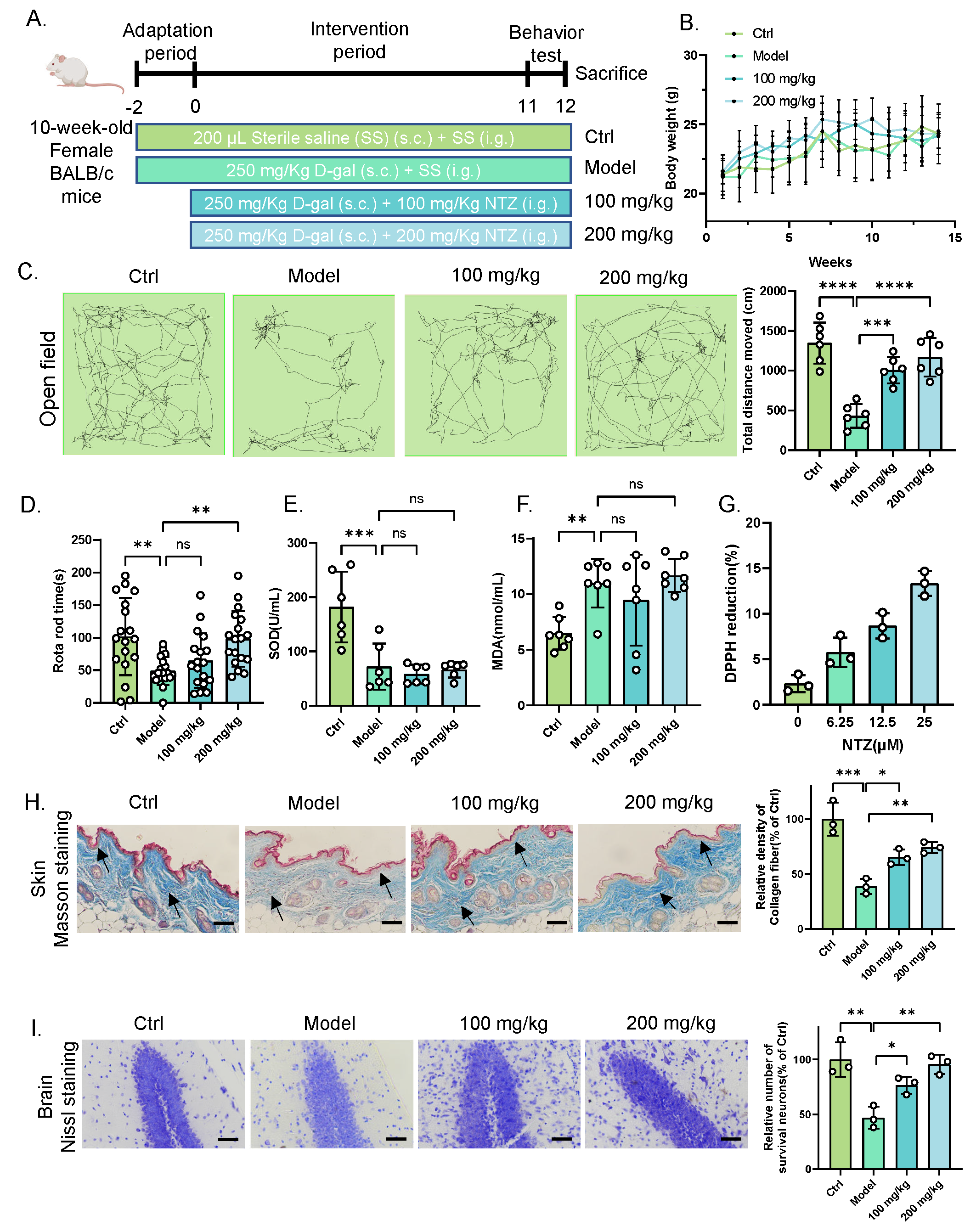

3.2. NTZ Ameliorated Senescence in D-gal-Induced Accelerated Aging Mice

To evaluate the anti-aging effect of NTZ in mammalian, we established an accelerated aging model by administering D-gal to BALB/c mice for 14 weeks (Figure 2A) following previous study [8]. During the experimental period, body weights increased by approximately 4 g across all groups, with no significant differences observed between the groups (Figure 2B). Behavioral and locomotor assessments revealed significant improvements in the NTZ-treated group compared to the D-gal group. Specifically, NTZ-treated mice traveled a greater distance in the open field center and spent more time on the rota-rod, indicating enhanced locomotor activity and motor coordination (Figure 2C,D).

Antioxidant activity in the serum was also assessed. D-gal treatment significantly reduced SOD activity and increased MDA levels, consistent with increased oxidative stress (Figure 2E,F). However, NTZ failed to reverse these changes suggesting that NTZ does not exert its anti-senescence effect via a direct antioxidative mechanism.

Histological analysis of skin tissue was conducted using Masson’s trichrome staining. In the D-gal group, as indicated by black arrows, the epidermis displayed an incomplete structure, an unclear basement membrane, and disorganized collagen fibers. NTZ treatment partially reversed these morphological and structural changes, indicating improved skin tissue integrity (Figure 2G). Additionally, we assessed brain damage by performing Nissl staining of the hippocampal region. The D-gal-treated group exhibited a reduced number of Nissl bodies in hippocampal neurons and a disordered neuronal arrangement. NTZ treatment protected hippocampal neurons from Nissl body loss and preserved neuronal integrity (Figure 2H). These findings suggest that NTZ exerts a significant anti-aging effect in the D-gal-induced accelerated aging mouse model, improving behavior, tissue morphology, and neuronal integrity, albeit without directly reversing oxidative stress.

3.3. NTZ Modulates Anti-Aging Effects via PI3K Signaling Pathway

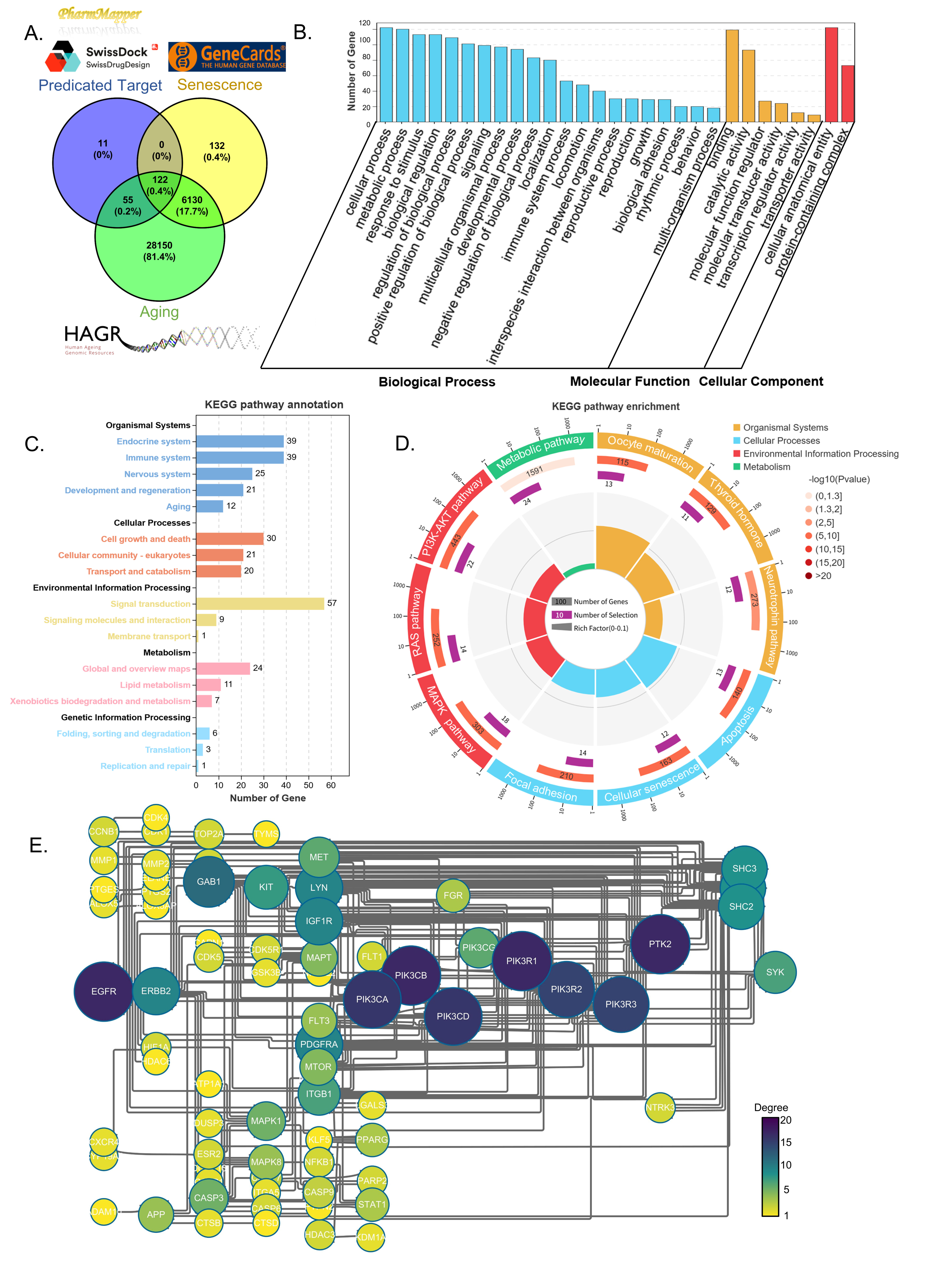

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying NTZ’s anti-aging effects, we performed computational target prediction and pathway analysis. Using the SwissTargetPrediction [15] and PharmMapper databases [16], we identified 122 potential anti-aging targets of NTZ by intersecting the predicted NTZ targets with senescence- and aging-related genes (Figure 3A).

GO analysis revealed significant enrichment of these targets in biological processes such as “metabolic processes”, “response to stimulus”, and “biological regulation.” At the molecular function level, the targets were notably enriched in activities related to “binding”, “catalytic activity”, and “molecular function regulation.” In terms of cellular components, the targets were particularly enriched in “cellular anatomical entities” and “protein-containing complexes” (Figure 3B).

KEGG pathway annotation showed that NTZ targets were significantly enriched in pathways critical for “signal transduction” (Figure 3C). Among the top 10 enriched pathways, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (ko04151) was the most significantly affected, involving 22 target genes directly associated with cell survival, metabolism, and stress resistance (Figure 3D). Additional pathways included the MAPK signaling pathway (ko04010), focal adhesion (ko04510), cellular senescence (ko04218), progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation (ko04914), and neurotrophin signaling (ko04722), all of which are linked to age-related tissue degeneration and physiological decline [22,23]. These findings align with our previous observations of NTZ modulating PI3K signaling in pulmonary fibrosis, suggesting that this mechanism is conserved across different aging models [12].

To further explore the mechanism of NTZ, we constructed a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network using STRING and Cytoscape. PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3CD, PIK3CG, PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3, subunits of PI3K in the PI3K signaling pathway, emerged as central hub nodes with high connectivity (Figure 3E). Functional clustering analysis revealed that PI3K interacts with key aging regulators such as IGF1R, mTOR, and EGFR, forming a core module involved in metabolism and senescence control. This aligns with NTZ’s previously documented effects on modulating cell proliferation, autophagy, and metabolic homeostasis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis [24,25], underscoring PI3K pathway engagement as a pivotal mechanism driving its anti-aging activity. These analyses demonstrated that NTZ exert its anti-aging effects by targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway through interaction with PI3K subunits, a conserved hub in cellular senescence and organismal aging [26]. This provides molecular evidence for NTZ’s role in modulating aging-related signaling cascades.

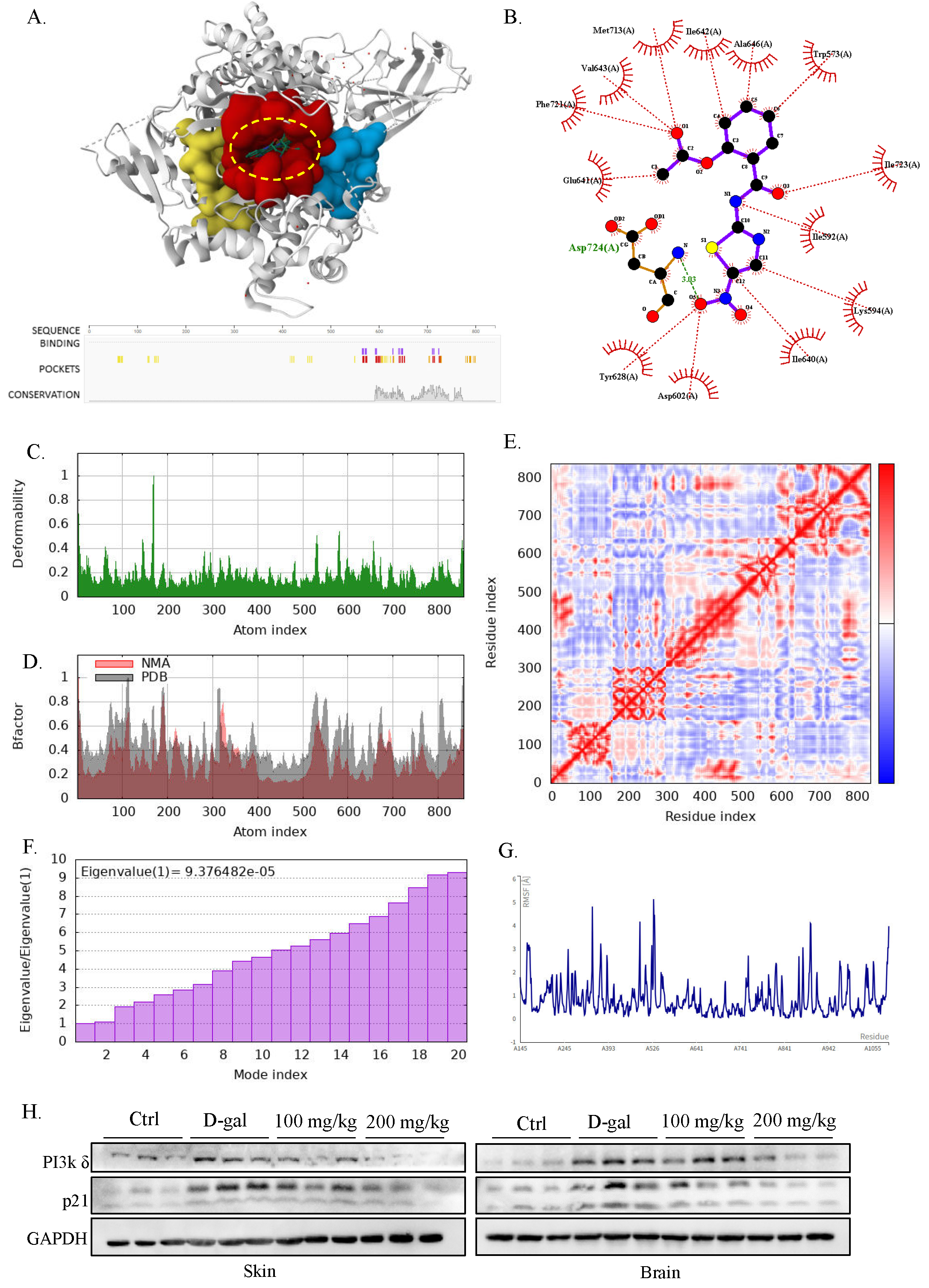

3.4. NTZ Exhibits High Affinity and Stable Binding to the PI3K

To validate the computational prediction that PI3K kinase is a key target of NTZ, we performed molecular docking and dynamics simulations to characterize their interaction. PrankWeb analysis [18] identified three potential binding pockets in the human PI3K p110 subunit, with the majority of these located between amino acid residues 550–750 (Figure 4A). Among these, pocket 1 (residues 560–740), a known binding site for pan-PI3Ks inhibitors [27], demonstrated the highest compatibility with NTZ. Molecular docking revealed that NTZ preferentially bound to pocket 1 with a binding energy of −8.3 kcal/mol, forming a stable hydrogen bond with Asp724 and extensive hydrophobic interactions with surrounding residues (Figure 4B). This binding affinity was stronger than that of the other two pockets, highlighting pocket 1 as the primary interaction site.

Molecular dynamics simulation further validated this interaction. The deformability profile of the binding region showed a peak value of 0.2, indicating moderate flexibility that allows for conformational adaptation without excessive structural distortion—an optimal characteristic for ligand-receptor interactions (Figure 4C). NMA-derived B-factor values averaged around ~0.2 across the complex, suggesting minimal disruption to the protein’s natural thermal motion, which confirms stable binding without compromising PI3Kγ structural integrity (Figure 4D). Covariance analysis highlighted strong cooperative motion within the binding pocket, with dense red regions indicating coordinated movements of key residues upon NTZ binding, stabilizing the ligand-receptor interface (Figure 4E). The eigenvalue spectrum displayed moderate conformational changes, suggesting that the protein adapts to ligand binding without unfolding (Figure 4F). The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of the binding site residues ranged from 0.5–2.5 Å, consistent with stable yet dynamic interactions that facilitate functional signaling modulation (Figure 4G). To further validate this interaction in vivo, we examined PI3Kδ expression in both skin and brain tissues from D-galactose-induced aging models. NTZ treatment leads to a significant reduction in PI3Kδ expression in these tissues (Figure 4H). Collectively, these results demonstrate that NTZ forms a stable, high-affinity complex with PI3Ks, corroborating our computational target prediction and previous study. This interaction likely disrupts PI3K mediated conserved aging regulatory axis, thereby mediating NTZ’s anti-aging effects.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that NTZ extends both lifespan and health span in C. elegans and D-galactose-induced aging mice. In nematodes, NTZ treatment reduced lipofuscin accumulation, decreased ROS levels, and improved locomotor activity—a hallmark of healthspan improvement. In mice, NTZ ameliorated cognitive and physical decline, protected hippocampal neurons from degeneration, and preserved skin tissue integrity.

C. elegans represents a natural physiological aging model, where senescence progresses via endogenous processes: gradual mitochondrial dysfunction, declining antioxidant capacity, and accumulation of cellular damage [13]. NTZ’s efficacy here—reducing ROS, clearing lipofuscin, and preserving locomotion—demonstrates its ability to modulate conserved endogenous aging processes. In contrast, the D-gal model is an accelerated aging model, where excessive D-gal triggers oxidative stress and accelerates tissue damage [8]. NTZ’s performance here reveals a critical advantage: unlike direct ROS scavenger, NTZ targets the functional sequelae of senescence. It likely acts by reducing cellular vulnerability to stress and sustaining tissue homeostasis, even in the face of overwhelming oxidative stress. Notably, as a clinically approved drug with an established safety profile, NTZ bridges preclinical anti-aging research and translational applications—positioning it as a promising candidate to address both natural aging and age-related decline driven by external stressors.

Computational target prediction and pathway analysis identified 122 potential anti-aging targets of NTZ. We propose that NTZ exerts its anti-aging effects through the modulation of the PI3K signaling pathway, a central regulator of cellular senescence and aging. Network pharmacology revealed PI3K p110 catalytic isoforms as central hub genes. By targeting PI3Ks, NTZ delays age-related physiological decline and enhances overall vitality, positioning it as a potential candidate for anti-aging therapies.

In line with previous studies, which showed that both NTZ and its metabolite tizoxanide extend lifespan in C. elegans [11], we not only confirm the anti-aging effects of NTZ in C. elegans but also extend these findings by demonstrating its anti-aging effects in a mammalian accelerated aging model. The improvement in cognitive and physical function in D-gal-induced aging mice, along with the protection of neuronal health and skin tissue integrity, suggests that NTZ may have therapeutic potential for a range of age-related diseases. Mechanistically, previous studies focused on the AMPK/SIR2.1/DAF-16 pathway, where the molecular targets of NTZ were less clearly defined [11]. Our research, however, identifies the PI3K signaling pathway as the primary upstream regulatory mechanism underlying NTZ’s anti-aging effects. NTZ works as a pan-PI3Ks inhibitor in mediating its anti-aging effects. This aligns with our earlier findings, where we showed that NTZ inhibits cellular senescence and alleviates pulmonary fibrosis, a senescence-related disease, suggesting a consistent molecular mechanism across different aging models [12].

PI3K has been widely studied as a pivotal regulator of aging and age-related diseases, integrating signals from growth factors, nutrients, and stress to control cell survival, metabolism, and senescence [26]. The PI3K-Akt pathway governs key aging hallmarks. Different subtypes of the PI3K p110 catalytic isoforms have varying effects on a variety of biological processes associated with senescence, including genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [28]. The activation of the PI3K signaling pathway has been observed in senescent cells, and PI3Ks inhibitors have been reported to increase telomerase activity and extend lifespan, addressing several aging-related phenomena, including mitochondrial dysfunction, genomic instability, and inflammation [29,30]. In aging nematodes, reduced PI3K signaling extends lifespan by activating DAF-16/FOXO, while in mammals, hyperactive PI3K expression accelerates cellular senescence and fibrosis [31,32]. Our study aligns with this framework, showing that NTZ inhibits PI3Ks. However, the precise molecular mechanisms within specific tissues and organs deserve further exploration.

In conclusion, our study provides robust evidence supporting NTZ as a novel anti-aging agent, expanding on previous work while offering new insights into its molecular mechanisms. By targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway, NTZ appears to modulate conserved aging-related signaling cascades, providing a promising approach to delay aging and combat age-related diseases. These findings pave the way for further clinical exploration of NTZ, with the potential to improve healthspan and lifespan in aging individuals. Future research could explore the synergistic effects of NTZ with other anti-aging therapies, as well as its broader clinical applicability in aging-related diseases.

Author Contributions

X.W.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. H.L.: Resources, Methodology, Investigation. X.W.: Supervision, Resources. H.Z.: Supervision, Resources. X.C.: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macau SAR (0070/2022/A2, 005/2023/SKL), the Research Fund of University of Macau (MYRG-GRG2023-00072-ICMS-UMDF), and the Ministry of Education Frontiers Science Centre for Precision Oncology, University of Macau (SP2025-00001-FSCPO). The authors would like to thank J.L. and E.W. of the University of Macau for their assistance in the open-field experiment and the rota-rod test.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau (approval code UMARE-019-2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will supply the relevant data in response to reasonable requests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

No AI tools were utilized for this paper.

References

- 1.

Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; et al. Cellular senescence: The good, the bad and the unknown. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00601-z.

- 2.

Kroemer, G.; Maier, A.B.; Cuervo, A.M.; et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: Understanding and managing aging. Cell 2025, 188, 2043–2062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.03.011.

- 3.

Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 958–978. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-024-00727-x.

- 4.

Parkhitko, A.A.; Filine, E.; Mohr, S.E.; et al. Targeting metabolic pathways for extension of lifespan and healthspan across multiple species. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101188.

- 5.

Campisi, J.; Kapahi, P.; Lithgow, G.J.; et al. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature 2019, 571, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1365-2.

- 6.

Folch, J.; Busquets, O.; Ettcheto, M.; et al. Experimental Models for Aging and their Potential for Novel Drug Discovery. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1466–1483. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666170707155345.

- 7.

Cho, J.; Park, Y. Development of aging research in Caenorhabditis elegans: From molecular insights to therapeutic application for healthy aging. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2024.100809.

- 8.

Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. D-Galactose-induced accelerated aging model: An overview. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-019-09837-y.

- 9.

Lokhande, A.S.; Devarajan, P.V. A review on possible mechanistic insights of Nitazoxanide for repurposing in COVID-19. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 891, 173748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173748.

- 10.

Rossignol, J.F. Nitazoxanide: A first-in-class broad-spectrum antiviral agent. Antiviral Res. 2014, 110, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.014.

- 11.

Li, W.; Chen, S.; Lang, J.; et al. The clinical antiprotozoal drug nitazoxanide and its metabolite tizoxanide extend Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan and healthspan. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 3266–3280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2024.03.031.

- 12.

Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Nitazoxanide alleviates experimental pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the development of cellular senescence. Life Sci. 2025, 361, 123302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.123302.

- 13.

Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. Protocol for assessing the healthspan of Caenorhabditis elegans after potential anti-aging drug treatment. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102285.

- 14.

Kong, S.Z.; Li, J.C.; Li, S.D.; et al. Anti-Aging Effect of Chitosan Oligosaccharide on d-Galactose-Induced Subacute Aging in Mice. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16060181.

- 15.

Gfeller, D.; Grosdidier, A.; Wirth, M.; et al. SwissTargetPrediction: A web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W32–W38. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku293.

- 16.

Liu, X.; Ouyang, S.; Yu, B.; et al. PharmMapper server: A web server for potential drug target identification using pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W609–W614. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq300.

- 17.

Mu, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; et al. OmicShare tools: A zero-code interactive online platform for biological data analysis and visualization. Imeta 2024, 3, e228. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.228.

- 18.

Jendele, L.; Krivak, R.; Skoda, P.; et al. PrankWeb: A web server for ligand binding site prediction and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W345–W349. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz424.

- 19.

Lopez-Blanco, J.R.; Aliaga, J.I.; Quintana-Orti, E.S.; et al. iMODS: Internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W271–W276. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku339.

- 20.

Kuriata, A.; Gierut, A.M.; Oleniecki, T.; et al. CABS-flex 2.0: A web server for fast simulations of flexibility of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W338–W343. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky356.

- 21.

Blagosklonny, M.V. The goal of geroscience is life extension. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.27882.

- 22.

Anerillas, C.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Regulation of senescence traits by MAPKs. Geroscience 2020, 42, 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-020-00183-3.

- 23.

Numakawa, T.; Odaka, H. The Role of Neurotrophin Signaling in Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Cognitive Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147726.

- 24.

Fan, L.; Qiu, X.X.; Zhu, Z.Y.; et al. Nitazoxanide, an anti-parasitic drug, efficiently ameliorates learning and memory impairments in AD model mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 1279–1291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-019-0220-1.

- 25.

Shou, J.; Wang, M.; Cheng, X.; et al. Tizoxanide induces autophagy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-019-01202-4.

- 26.

O'Neill, C. PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling: Impaired on/off switches in aging, cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 647–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.025.

- 27.

Liu, Q.; Shi, Q.; Marcoux, D.; et al. Identification of a Potent, Selective, and Efficacious Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase delta (PI3Kdelta) Inhibitor for the Treatment of Immunological Disorders. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5193–5208. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00618.

- 28.

Fox, M.; Mott, H.R.; Owen, D. Class IA PI3K regulatory subunits: p110-independent roles and structures. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1397–1417. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20190845.

- 29.

Le, Q.V.; Wen, S.Y.; Chen, C.J.; et al. Reversion of glucocorticoid-induced senescence and collagen synthesis decrease by LY294002 is mediated through p38 in skin. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 6102–6113. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.73915.

- 30.

Tan, P.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, S.; et al. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway regulates the replicative senescence of human VSMCs. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2016, 422, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-016-2796-9.

- 31.

Hay, N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 1965–1970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.013.

- 32.

Bhatt, J.; Ghigo, A.; Hirsch, E. PI3K/Akt in IPF: Untangling fibrosis and charting therapies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1549277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1549277.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.